By the close of 1779 British possessions in the revolted colonies were confined in the north to New York City, Long Island, and Penobscot. An army had been lost at Saratoga. In the south a tenuous hold on lower Georgia had been gained, East and West Florida had remained loyal, but West Florida was threatened by Spain. Elsewhere in the revolted colonies the revolutionaries were firmly in control.

Britain was losing the war.

To turn the tide a bold strategy was evolved. By a series of campaigns beginning in the south at Charlestown the British would move north through the Carolinas into Virginia and form the numerous loyalists of the Carolinas into militia as they progressed. Material reliance would be placed on the militia to maintain control of the territory that had been conquered, freeing regular and British American troops for the onward advance. If all went well, the south would be recovered and civil government eventually reinstated there under the Crown.

A most important factor in the equation was the paucity of available troops. General Sir Henry Clinton, the British Commander-in-Chief, had at his disposal an entire force which at most amounted to only 32,000 men of all ranks fit for duty, including the troops in Georgia and the Floridas. Of these, 14,000 to 17,500 men were required to maintain the posts at New York and Long Island, so that only a dangerously small balance remained for service in other quarters.

If the strategy were to succeed, a new base—Charlestown—had first to be taken and held. As the troops advanced into the interior, posts had to be established to support the militia in maintaining control of conquered territory, and lines of communication sufficiently guarded. In short, two complete armies were really required: one in the south; and another at New York to hold the forces of New England in check and deter an offensive against Canada. It would be Clinton’s task to make one army do the work of two by relying on the sea for communication between the different parts of his force. If command of the sea were kept, the troops detached to the south could if necessary be supported and might succeed; if command of the sea were lost, they or part of them ran the risk of defeat in detail.[1]

Embarking on the first step in the strategy—the Charlestown campaign, Clinton set sail from New York on December 26, 1779 during the coldest winter in living memory.[2] Accompanied by Cornwallis and 8,700 troops, he arrived off Tybee, Georgia, at the end of January, having been escorted by ships of war under the command of Marriot Arbuthnot, the naval Commander-in-Chief. Despite a harrowing passage almost all the troops arrived safely, but few horses survived and much of the artillery was lost together with many valuable supplies.

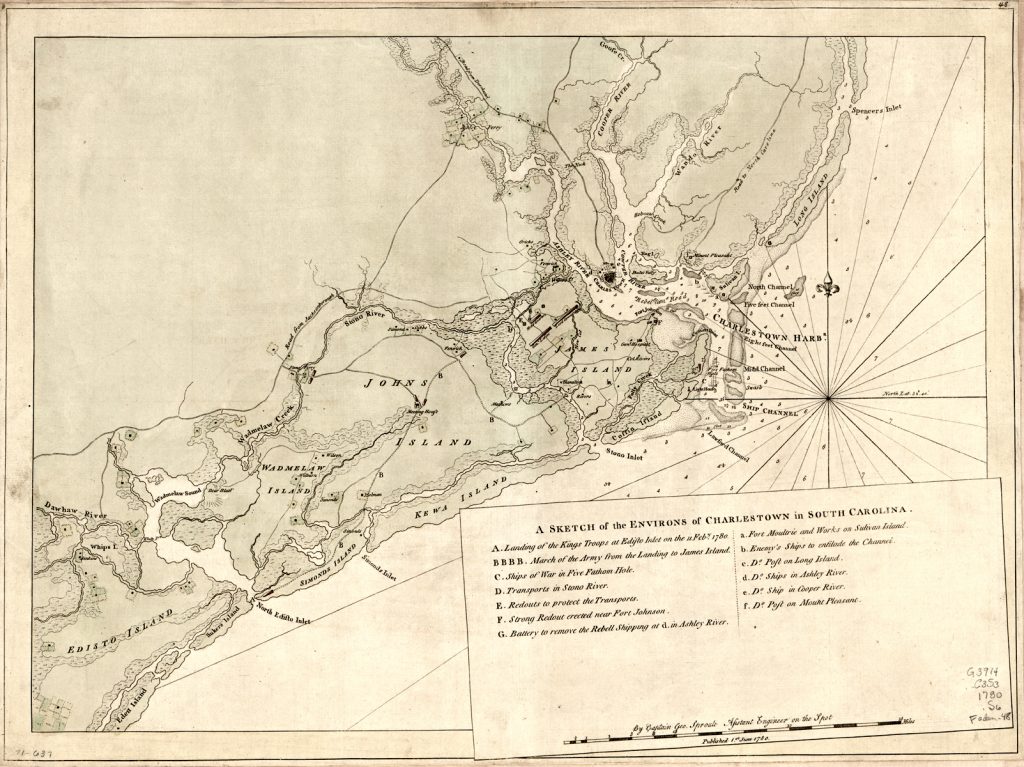

On February 10 Clinton sailed for Simmons (now Seabrook) Island, South Carolina, and began landing troops there the following day. Advancing cautiously on Charlestown, he eventually established himself on Charlestown Neck on March 29 and three days later broke ground within 800 yards of the town’s defenses. In the meantime he had been reinforced with 1,500 troops from Georgia under Brigadier General James Paterson, a corps which had at first been intended for a diversionary move on Augusta.

Charlestown lay at the tip of a peninsular (“the Neck”) bounded on the west by the Ashley River, on the east by the Cooper, and on the south and south-east by the harbor. Occupying it was a combined force of Continental troops and militia commanded by Major General Benjamin Lincoln. At the capitulation it would have been augmented to almost 5,500 men.

Not the sharpest tool in the box, Lincoln had been seduced by Clinton’s leisurely advance into concluding that he might strengthen Charlestown’s defenses in time to withstand a siege. It would prove a fatal mistake. Not only would he lose the garrison and town but by concentrating his available force there he would open the whole of South Carolina to control by the British.

Having completed the first parallel of his approaches and erected batteries there, Clinton joined with Arbuthnot on April 10 in issuing a summons to surrender. It was rejected. Lincoln was now invested on three sides: by Clinton’s forces to the north and west of Charlestown and by Arbuthnot’s frigates in the harbor. The only way open lay to the east across the Cooper River, where a number of revolutionary vessels were sunk or anchored behind a log-and-chain boom to obstruct passage by the Royal Navy.

To close the noose around the town Clinton detached Lt. Colonel James Webster to the east of the Cooper on April 12, placing under his command a corps of 1,400 men comprising the 33rd and 64th Regiments, Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarleton’s British Legion, and Major Patrick Ferguson’s American Volunteers. Only two days had elapsed when Tarleton and Ferguson routed the only revolutionary force operational in the field west of the Santee, a body of Continental cavalry and militia posted at Monck’s Corner.

In the meantime Clinton’s approaches were progressing steadily under the supervision of the commanding engineer, Major James Moncrief, and by April 19 they were within 250 yards of the lines of Charlestown. Convinced at last of the hopelessness of his situation, Lincoln proposed two days later a capitulation allowing the unmolested withdrawal of his garrison to whatever destination he chose, together with that of the shipping. The proposal was rejected.

On the 18th Colonel Francis Lord Rawdon , commander of the Volunteers of Ireland, a British American regiment that he had raised, arrived from New York with a reinforcement of 2,566 rank and file effectives, of whom 1,863 were fit for duty. It enabled Clinton to strengthen the corps east of the Cooper, which on April 23 was placed under the command of Lt. General Earl Cornwallis.

Cornwallis was now in his forty-second year. Educated partly at Eton, he was disfigured there for life when he was accidentally struck in the eye during a game of hockey. Instead of going on to Oxford or Cambridge, he attended the military academy at Turin for several months before taking part in the European theatre of the Seven Years’ War, first as an aide-de-camp to Lt General the Marquess of Granby, and second as lieutenant colonel of the 12th Regiment. In the years after the war he became, inter alia, an aide-de-camp to the King (1765), colonel of the 33rd Regiment (1766), Vice-Treasurer of Ireland (1769), Privy Councillor (1770), and Constable of the Tower of London (1771). Politically, he had the foresight to vote against the Stamp and Declaratory Acts and generally sympathised with the grievances of the American colonists. Nevertheless, his sympathy did not extend to support for breaking the constitutional ties with the Crown. After the Revolutionary War broke out, he was promoted to major general (September 29, 1775) and shortly after to lieutenant general in North America (January 1, 1776). He went on to take part in the New York, New Jersey, and Philadelphia campaigns and in the Battle of Monmouth. A dynamic officer best suited to offensive operations, he was beloved by the troops, who would have gone—and did go—through hell and high water for him. Possessing many admirable qualities, not least affability, high courage, decisiveness, endurance, honesty, humanity and self-assurance, he was tactically astute, but as I have revealed elsewhere, he was temperamentally unsuited to defensive warfare and would display a crucial lack of strategic awareness at a critical juncture.[3] Third in the chain of command behind Clinton and Lt. General Freiherr Wilhelm von Knyphausen, he held a dormant commission to succeed Clinton should the latter die or become incapacitated.

By now relations between Clinton and Cornwallis were strained. At first the two men were friends, but in 1777 Clinton had taken exception to Cornwallis advising General Sir William Howe of a derogatory comment that Clinton had made privately about the then Commander-in-Chief. On the surface the two patched up their relationship, but Clinton had a long memory.

Another fly in the ointment was Clinton’s perception of Cornwallis’s recent behavior. In the summer of 1779 Clinton had written to Lord George Germain, the British Secretary of State, submitting his resignation. It was widely expected that Cornwallis would be named to succeed him, but neither man had any way of knowing when or if the succession would occur. While awaiting Germain’s reply, Clinton had felt it prudent to consult Cornwallis on every step in the Charlestown campaign, but it was not the involvement of Cornwallis that caused Clinton’s irritation. Rather it was his conviction that Cornwallis was tattling behind his back and persuading many officers to act as if Cornwallis had succeeded to the command. For this and other reasons Clinton considered Cornwallis guilty of unfriendly and unmilitary conduct.

On March 19 Clinton had received Germain’s long awaited reply. It advised him that the King, for all his confidence in Cornwallis, was too well satisfied with Clinton’s conduct to wish to see the command in any other hands. Instead of lancing Clinton’s irritation with Cornwallis, it only served to exacerbate it, for Cornwallis, no doubt deeply disappointed, reacted by asking not to be consulted any longer on plans. Quite legitimately Clinton took the view that he was entitled to a subordinate’s advice whenever he wished it. Of course he might have compelled Cornwallis to give his views formally in a council of the general and field officers, but he feared that they would carry too much weight there. What he really wanted was to be able to continue consulting Cornwallis privately. By closing the door on this alternative, Cornwallis irritated Clinton more.

Clinton for his part was not the easiest of men to serve under. The son of an admiral who had served as Governor of New York, he was a first cousin of the Duke of Newcastle and had entered the army in 1745. After serving for four years as an aide-de-camp to Lord Ligonier, the Commander-in-Chief in Britain, he went off in 1760 to the European theatre of the Seven Years’ War as a captain and lieutenant colonel in the 1st Regiment of Foot Guards (the Grenadier Guards), but instead of serving with the regiment, he acted as aide-de-camp to the Duke of Brunswick, an officer of superior ability. In late 1762 he returned to London as a colonel and two years later was appointed a groom of the bedchamber to the Duke of Gloucester, the King’s favourite brother. It was a post he would occupy for many years, even while he was in North America. In May 1772 he was promoted to major general and two months later was elected to the Commons as the Member for Boroughbridge, becoming the Member for Newark in 1774. A supporter of the North administration, he dreaded the direction that its American policy was taking and hoped against hope that the quarrel with the colonies would not come to war. Nevertheless, as a serving officer, he considered it his duty to go out with Howe to Boston in 1775, and when Howe succeeded to the overall command in September, Clinton became his second. Less than three years later he replaced Howe as Commander-in-Chief, having by then become a full general and a Knight of the Bath.

Shy and diffident, Clinton did not mingle easily. Possessing fragile self-confidence, with an underlying sense of inadequacy, he reacted in typical ways when dealing with fellow officers. As a subordinate, he was overassertive, overcritical, and overly resentful when his advice was rejected. As Commander-in-Chief, he was prickly, belittling of his colleagues, and quick to assume they were incompetent. Perceived grievances he stored up aplenty. Yet, for all his faults, he was proving to be a humane and—for the time being—able Commander-in-Chief, who would soon capture Charlestown with the minimum of losses, always an important factor when highly trained regulars were too few to waste. On April 16 he had just celebrated his fiftieth birthday.

So on April 23, having requested a separate command, Cornwallis was detached to take charge of Webster’s strengthened corps east of the Cooper. It was a step which Clinton promptly regretted, uneasy as he was at having his second out of sight. “He will play me false,” he feared, a premonition which would come true, not in the Charlestown campaign, but later.[4]

Of the principal events which now unfolded in Cornwallis’s sphere of operations, only the action of May 6 at Lenud’s[5] Ferry on the Santee, in which Tarleton routed a force of enemy cavalry, was removed from the immediate vicinity of Charlestown. The rest were the taking possession of Haddrell’s Point on April 25, the enemy’s evacuation of the fort at Lemprière’s on the 28th, Ferguson’s capture of the redoubt at Mount Pleasant on May 2, and the surrender of Fort Moultrie to the navy five days later.

Meanwhile on the Neck Clinton had been cautiously advancing. By early May his troops were so close to Charlestown that they had drained almost dry a canal protecting the defensive works. As far as he was concerned, the only blot on the landscape, aside from his suspicions of Cornwallis, was Arbuthnot’s refusal, despite assurances to the contrary, to consolidate the town’s investment by sending frigates into the Cooper. A risky venture it would have been, but Arbuthnot’s volte-face did not endear him to Clinton.

Arbuthnot was now approaching his seventieth year and looked much older. After an undistinguished naval career he was promoted to vice admiral of the blue on March 19, 1779 and came out to the North American station as the naval Commander-in-Chief in the summer of that year. A flawed officer past his prime, he was the worst possible choice for the job. There are those in authority—we all have met them—who take pleasure from displaying their power in a negative way by frustrating the will of others. Arbuthnot was just such a man. That there was in his make-up a flaw of this kind is revealed later in The Cornwallis Papers by the almost grovelling way in which he is addressed by other officers. Negative, inconsistent and unreliable, he would, in short, have tried the patience of a saint—and Clinton was no saint.

On May 8 Clinton and Arbuthnot issued a further summons to surrender. It was rejected, but a terrifying bombardment of the town and the threat of an imminent assault broke the will of the inhabitants, who petitioned Lincoln to capitulate. He now accepted the terms which had previously been offered. The Continental troops and sailors were to be prisoners of war, whereas the civil officers, armed citizens of Charlestown, and the militia then in garrison were to become prisoners on parole and to be secured in their persons and property. The militia would be permitted to go home. All other persons in the town were to be prisoners on parole.

On May 12 the defenders marched out and delivered up the town together with a mass of ordnance, shot, powder, firearms and ammunition. It was the greatest victory so far gained by the British in the war.

The Union Jack was raised on the ramparts and again flew over Charlestown.

Bibliography

Anthony Allaire, “Diary”, Appendix to Lyman C. Draper, King’s Mountain and its Heroes (Cincinnati, 1881)

Mark Mayo Boatner III, Encyclopedia of the American Revolution(D. McKay Co., 1966)

Sir Henry Clinton, The American Rebellion, edited by William B. Willcox (Yale University Press, 1954)

Sir John Fortescue,A History of the British Army, vol. III (Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1902)

Edward McCrady, The History of South Carolina in the Revolution 1775-1780(The Macmillan Co., New York, 1901)

Ian Saberton ed., The Cornwallis Papers: The Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Theatre of the American Revolutionary War, 6 vols (Uckfield: The Naval & Military Press Ltd., 2010)

Charles Stedman, History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War(London, 1792)

Banastre Tarleton, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Provinces of North America(London, 1787)

Bernhard A. Uhlendorf ed., The Siege of Charleston(University of Michigan Press, 1938)

Christopher Ward, The War of the Revolution(The Macmillan Co., New York, 1952)

Franklin and Mary Wickwire,Cornwallis: The American Adventure(Houghton Mifflin Co., 1970)

William B. Willcox, Portrait of a General: Sir Henry Clinton in the War of Independence(Alfred A. Knopf, 1964)

[1]As would in fact occur with the disaster at Yorktown.

[2]“Had the expedition been delayed 48 hours longer, the whole fleet of transports would have been frozen fast in the river, as the frost that winter was more intense than the oldest American had ever known. Incredible as it may appear, it is an absolute fact that in a few days it froze so intensely that a regiment of cavalry, cannon and waggons passed from Long Island to Staten Island on the ice over a channel so deep as to admit the largest ships in the British navy to sail up to New York” (George Hanger,The Life, Adventures, and Opinions of Col. George Hanger (London, 1801).

[3]See Ian Saberton, “The Decision That Lost Britain The War: An Enigma Now Resolved,” Journal of the American Revolution, January 8, 2019.

Recent Articles

The Killing of Jane McCrea

The American Princeps Civitatis: Precedent and Protocol in the Washingtonian Republic

Thomas Nelson of Yorktown, Virginia

Recent Comments

"Decoding Connecticut Militia 1739-1783"

Hi, I'm looking for discussion in the records for troop movement and...

"General Israel Putnam: Reputation..."

Gene, see John Bell’s exhaustive Analysis, “Who Said ‘Don’t Fire Till You...

"The Deadliest Seconds of..."

Ed, yes Matlack's son was reportedly a midshipman on the Randolph. That...