After nearly a quarter of a millennium, what do we really know about the militia and state troops that served during the Revolutionary War? Historians and researchers over the past century have dedicated entire volumes to addressing this question with numerous publications of militia rosters. While this research has proven invaluable, what does it really tell us about the men and their units beyond their service in a particular unit or battle? For instance, how old was the typical militiaman (if there was a “typical” militiaman)? How long did he serve and in how many battles did he fight? Was he a volunteer or a reluctant draftee? Where did he serve? Was he literate? Where did he live after the war? And perhaps most importantly, what was his personal experience? What unique circumstances or events did he have a part in that is not covered in already written histories of the war?

Information contained within pension applications provides at least some answers. In the past fifteen years, most of the 150,000 known Revolutionary War pension documents have been digitally scanned.[1] Tens of thousands of these have been transcribed and posted in online databases. The most prominent repository of these transcribed pension documents is the Southern Campaigns Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters website. Researchers Will Graves, C. Leon Harris, and several others have, since 2006, meticulously deciphered and transcribed thousands of pension applications. To date there are over 25,000 transcribed documents on the site. All of the known Federal pension applications from men who served in Georgia, South and North Carolina, and Virginia have been posted there.[2]

This work is a demographic study of the North Carolina militia and state troops utilizing data derived from Federal Pension applications. Included are men of the North Carolina Continental Line who also served in the militia or state troops. In the interest of keeping this piece relatively brief and to avoid confusion, men who served exclusively in the North Carolina Continental Line have been excluded from this work. Clearly, North Carolina Continental soldiers warrant their own dedicated study.

North Carolina fielded between 30,000 and 36,000 soldiers during the war, of which 22,000 to 28,000 were militia and state troops.[3] Between fifteen and twenty percent of these men (or their families) filed pension applications.[4] For this study over 9,000 applications were reviewed pertaining to North Carolina. Of these, data from only 3,721 applications was collected and entered into a simple spreadsheet. The two critical requirements to be included were that the men entered military service in North Carolina and provided details about themselves and their service. Generally, this included date and place of birth, place of enlistment, dates of service, type of enlistment, duration of service, place of pension location, and participation in battles or skirmishes. If an application provided little more than a name and only a vague description of a man’s service it was not included.

Pension Acts

There were numerous laws providing pensions for Revolutionary War soldiers. The first started with the Continental Congress during the Revolution and the last act was passed after the Civil War. Two particular Pension Acts, those of 1818 and 1832, yielded 53,910 pensions of the overall 57,623 awarded.[5] Briefly summarized, the 1818 act provided pensions for Continental soldiers who did not desert, served at least nine months, and who were suffering financial hardship. The 1832 Act extended full pensions to militia, state troops, and Continentals who had served at least twenty-four months, regardless of financial circumstances, and partial pensions to those who had served at least six months.

Before venturing into the demographics, readers should be advised that this was not intended to be a definitive study of all North Carolina militia and state troops. Nor is this work intending to capture information from all of the known North Carolina pension applicants. The data herein represents a small portion of the total number of men who served in the North Carolina militia and state troops who provided details about their time in these units. The analysis, summation, and synthesis here only applies to the data collected from the 3,721 pension applications.

A word of further caution is necessary regarding statistics on dates of birth, length of service, and number of terms the men served. Pension applicants almost certainly served more time, more tours of duty, and were younger than those who did not file applications. The minimum length of service requirements for pensions meant that those that served less than the minimum six or nine months and/or only one standard three-month term of service would be highly unlikely to file an application. Likewise, many descendants may have been less likely to file applications, as they may not have known the details of service or have been unable to provide third-party verification of the relative’s service. Pension applicants were likely to be younger because many men died before 1832 when most applications were filed. As life expectancy in eighteenth-century America was between forty-one and forty-seven years of age, it certainly seems possible, if not probable, that the men studied here represent the younger range of North Carolina soldiers.[6]

Place and Date of Birth

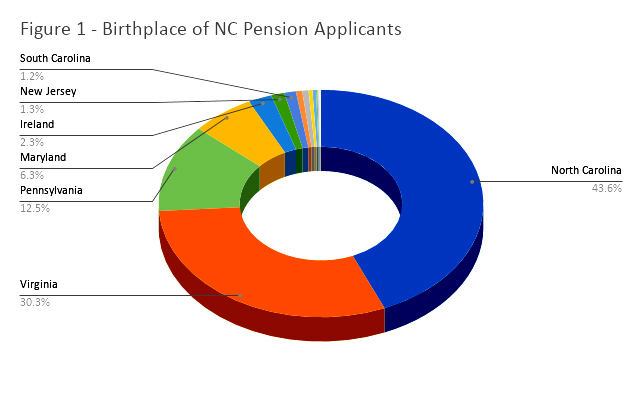

Most of the men who filed pension applications for North Carolina militia and state troop service were not born in the former colony. Over fifty-six percent were born in other colonies or other countries. More of these men were born in Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania than North Carolina, those colonies accounting for over forty-nine percent of all pension applicant places of birth. Those born in New Jersey and South Carolina account for just over one percent each, respectively. Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Massachusetts, New York, and Rhode Island were also noted as birthplaces, comprising a fraction of a percent for each state. Slightly over three percent of North Carolina pension applicants were foreign-born, arriving from six countries. Just over two percent were born in Ireland, less than one percent were born in Scotland. Fewer than a dozen men each were born in Canada, England, France, and Germany (Figure 1).

Over sixty-eight percent of those born out of state entered service in counties in the western half of North Carolina. Fairly prevalent in pension applications is a trend of those born out of state congregating in certain counties of North Carolina. For instance, seventy-six percent of those born in Ireland (Ulster) settled in the three counties of Guilford, Rowan, and Mecklenburg. Seventy-seven percent of those born in Scotland settled in the southeastern counties of North Carolina. Over eighty-six percent of those born in Pennsylvania settled in the five western counties of Guilford, Mecklenburg, Orange, Rowan, and Tryon. Just over sixty-two percent of those born in Virginia settled in the northern counties of North Carolina. The three counties with the highest percentages of those born out of state were the western counties of: Surry with seventy-six percent, Burke with seventy-seven percent, Wilkes with eighty-one percent, and Tennessee (then part of North Carolina) with eighty-three percent.

Over sixty-eight percent of those born out of state entered service in counties in the western half of North Carolina. Fairly prevalent in pension applications is a trend of those born out of state congregating in certain counties of North Carolina. For instance, seventy-six percent of those born in Ireland (Ulster) settled in the three counties of Guilford, Rowan, and Mecklenburg. Seventy-seven percent of those born in Scotland settled in the southeastern counties of North Carolina. Over eighty-six percent of those born in Pennsylvania settled in the five western counties of Guilford, Mecklenburg, Orange, Rowan, and Tryon. Just over sixty-two percent of those born in Virginia settled in the northern counties of North Carolina. The three counties with the highest percentages of those born out of state were the western counties of: Surry with seventy-six percent, Burke with seventy-seven percent, Wilkes with eighty-one percent, and Tennessee (then part of North Carolina) with eighty-three percent.

Conversely, most militia and state troop applicants in the eastern counties of the state were born in North Carolina. Over sixty-two percent of those from eastern counties report being born in the state. Very high rates of in-state birth were recorded in several inland eastern counties: Edgecombe with seventy-five percent, Pitt with eighty-two percent, Dobbs with eighty-three percent, Duplin and Hertford with eighty-four percent, Martin with eighty-five percent, and Craven with eighty-eight percent.

The average birth year of the men from the pension applications is 1757. The earliest birth year noted is 1732, the latest recorded is 1767. There is very little variation based on where in the state the man was born, or whether he was born inside or outside of North Carolina.

Length of Service and Number of Deployments

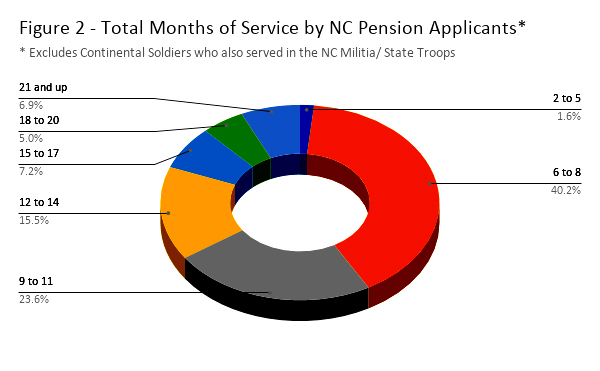

Most North Carolina pension applicants spent the better part of a year in militia and state troop service. Over sixty-three percent of men who were only in the militia and state troops served between six and eleven months. Excluding in this percentage are those Militiamen who served in the North Carolina Line.[7] Another twenty-one percent served between twelve and seventeen months. Over thirteen percent served eighteen or more months in the militia (Figure 2).

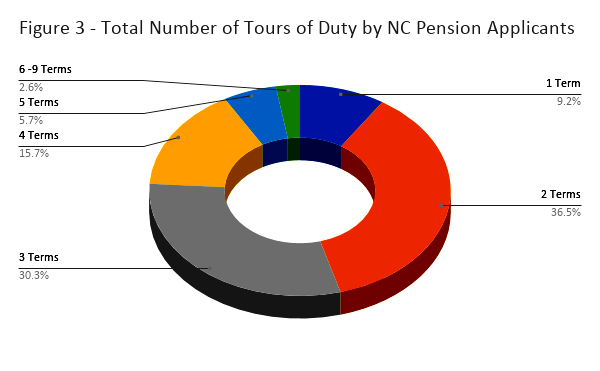

Of the 3,652 men that provided the number of occasions they served, there were a total of 9,450 individual tours of duty. Over the course of the war, ninety percent of all North Carolina pensioners served two or more terms in the militia and state troops. A small number of men (two percent) report serving an exceptional six or more tours of duty (Figure 3).

Of the 3,652 men that provided the number of occasions they served, there were a total of 9,450 individual tours of duty. Over the course of the war, ninety percent of all North Carolina pensioners served two or more terms in the militia and state troops. A small number of men (two percent) report serving an exceptional six or more tours of duty (Figure 3).

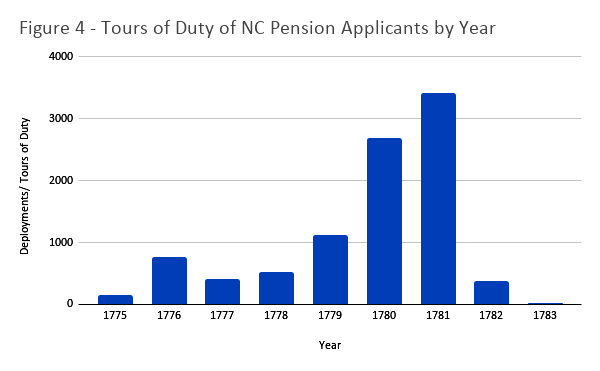

Given the dozens of battles and skirmishes in the South throughout 1780 and 1781 it is not surprising that most North Carolina men served tours and experienced combat during this period. Over seventy-five percent of the total tours of duty by pensioners were during 1780 or 1781. Ninety-one percent of all North Carolina pension applicants served at least one term of military service during 1780-1781. Over sixty-two percent of all men served two or more terms during this time frame (Figure 4).

Given the dozens of battles and skirmishes in the South throughout 1780 and 1781 it is not surprising that most North Carolina men served tours and experienced combat during this period. Over seventy-five percent of the total tours of duty by pensioners were during 1780 or 1781. Ninety-one percent of all North Carolina pension applicants served at least one term of military service during 1780-1781. Over sixty-two percent of all men served two or more terms during this time frame (Figure 4).

Terms of Service

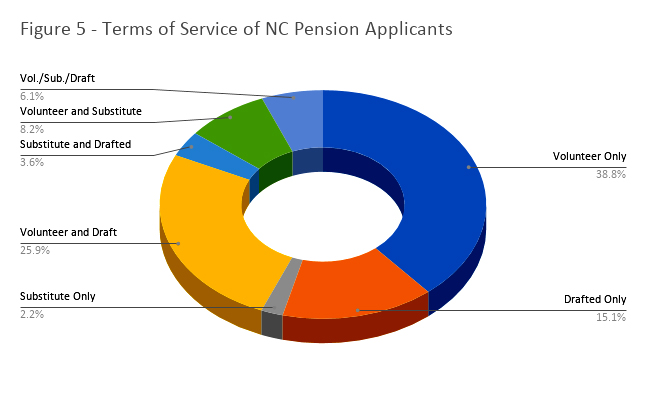

Pension applicants served a tour of duty in one of three ways: as a volunteer, draftee, or substitute.[8] More than thirty-eight percent served solely as a volunteer, fifteen percent as a draftee, and two percent as a substitute. The remainder of men served in more varied ways as a volunteer and draftee, volunteer and substitute, draftee and substitute, or all three. Despite the numerous conditions under which men served, the data is clear that a substantial majority of North Carolina applicants (upwards of eighty-four percent) actively chose to enter military service as a volunteer or substitute at least once during war. However, it is also true that half were drafted on at least one occasion (Figure 5).

There are several interesting anecdotes from substitutes in their applications. Many applicants describe paying money or providing goods to their substitute or receiving them to serve in another’s place. One man volunteered in 1777 but afterward coordinated with several other men to pay substitutes four times from 1777 to 1780.[9] Fairly common among substitutes are men serving in the place of a relative. Almost all these men substituted themselves in their fathers’ or brothers’ place. Perhaps the most interesting story of a substitute is that of Ishmael Titus. He was a slave who was substituted (it appears illegally) in his master’s place. As a reward for his service he was granted his freedom.[10] Titus’s example is the only known case in the North Carolina pension applications of a slave manumitted for their military service.[11]

There are several interesting anecdotes from substitutes in their applications. Many applicants describe paying money or providing goods to their substitute or receiving them to serve in another’s place. One man volunteered in 1777 but afterward coordinated with several other men to pay substitutes four times from 1777 to 1780.[9] Fairly common among substitutes are men serving in the place of a relative. Almost all these men substituted themselves in their fathers’ or brothers’ place. Perhaps the most interesting story of a substitute is that of Ishmael Titus. He was a slave who was substituted (it appears illegally) in his master’s place. As a reward for his service he was granted his freedom.[10] Titus’s example is the only known case in the North Carolina pension applications of a slave manumitted for their military service.[11]

Literacy

Pension applications were generally either signed by the applicant or with a “mark” if the applicant was not literate. Compilation of this data reveals that only fifty-three percent of pension applicants were literate (enough to sign their names).[12] There is some indication though that this percentage may be high as there are instances of court officials signing statements for the applicant. Even at fifty-three percent, the percentage indicates lower rates than indicated in colonial literacy studies. One study found that Perquimans County, North Carolina, had a seventy-nine percent literacy rate from 1748-76, and sixty-eight percent in Virginia in 1762-68.[13] The reason for this disparity is unknown but could be due to several factors. Schools in colonial North Carolina were few and widely scattered. The same academic study noted that increased population density generally correlated to higher rates of literacy which was just then occurring in North Carolina. Another study suggests that colonial literacy rates were inflated because the “unlanded poor,” who were more likely to be illiterate, were under-represented in legal documents, the primary method in determining literacy. That said, the few counties which seem to have had schools also had relatively high literacy rates. Mecklenburg County had the highest rate at seventy-three percent, New Hanover at sixty-eight percent, and Caswell at sixty-two percent.

Battles and Skirmishes

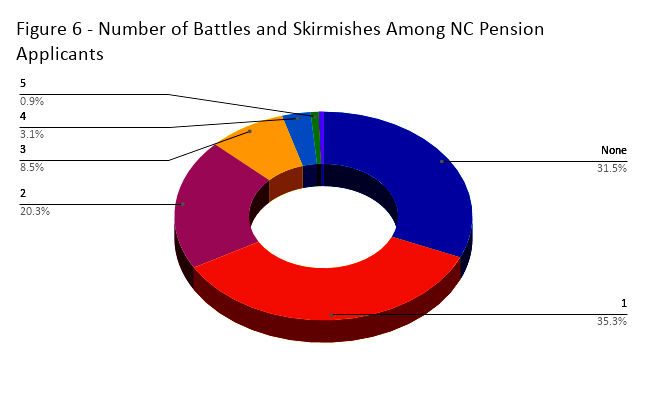

North Carolina militia and state troop pension applicants (including those who also served in the North Carolina Line) reported being in ninety-nine known battles and skirmishes in at least seven different states. At least sixty-eight percent of North Carolina pension applicants were involved in at least one battle or skirmish.[14] The highest proportion of men (thirty-five percent) reported being in one battle followed by those who fought in two battles (twenty percent). A very few, six men, reported being in seven or more battles and skirmishes during the war (Figure 6).

Of the ninety-nine battles, North Carolina pension applicants report themselves most prominently in eleven actions. The Battles of Camden and Guilford Courthouse have the highest number of reported pension applicant participation. Approximately nine percent of all North Carolina militia and state troop pensioners (including those with no previous battle experience) report being engaged in the Battle of Camden. Ten percent of the total sample were in the Battle of Guilford Courthouse. Of the eleven battles, six were fought outside of North Carolina. Three of these eleven battles were fought against primarily Loyalist units with very few if any British regular troops present (Figure 7).

Of the ninety-nine battles, North Carolina pension applicants report themselves most prominently in eleven actions. The Battles of Camden and Guilford Courthouse have the highest number of reported pension applicant participation. Approximately nine percent of all North Carolina militia and state troop pensioners (including those with no previous battle experience) report being engaged in the Battle of Camden. Ten percent of the total sample were in the Battle of Guilford Courthouse. Of the eleven battles, six were fought outside of North Carolina. Three of these eleven battles were fought against primarily Loyalist units with very few if any British regular troops present (Figure 7).

Of the 2,536 men that fought in at least one battle, seventy-eight percent saw combat in the 1780-81 time period. Of those that participated in the battles and skirmishes of 1780-81 only 381 (fifteen percent) report previous battle experience prior to 1780. About nine percent of men report being in unnamed skirmishes. Most of these were against British-aligned Native Americans on the western frontiers of North and South Carolina, Virginia, and Georgia. A smaller proportion of these unnamed skirmishes were with unnamed Tory units across both Carolinas between 1775 and 1781.

Of the 2,536 men that fought in at least one battle, seventy-eight percent saw combat in the 1780-81 time period. Of those that participated in the battles and skirmishes of 1780-81 only 381 (fifteen percent) report previous battle experience prior to 1780. About nine percent of men report being in unnamed skirmishes. Most of these were against British-aligned Native Americans on the western frontiers of North and South Carolina, Virginia, and Georgia. A smaller proportion of these unnamed skirmishes were with unnamed Tory units across both Carolinas between 1775 and 1781.

A few personal battle accounts of pensioners’ military actions stand out. As militia companies were formed locally, many men served with family members. Two separate men report relatives killed at the Battle of Ramsour’s Mill, one man’s father and another’s brother.[15] One man reported that his brother was killed by his side at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse.[16] Another man reported that both his brother and father were killed at the Battle of Kings Mountain.[17] A man who was on his way to the Kings Mountain but missed the action encountered captured Loyalist prisoners on his return home. Among the prisoners was his brother who was captured in the battle.[18]

Continental Army Service

Approximately twelve percent of North Carolina pension applicants served in the North Carolina Continental Line as well as in the militia and state troops.[19] Analysis of these pension applications support the two distinct periods in the history of the North Carolina Line. From May 1780 when 800 of them were captured at Charleston, to April 1781 when new regiments were raised, the North Carolina Continental Line had essentially ceased to exist. The vast majority of those who served in both the line and militia had either completed their Continental service before 1780, serving in the militia later or served in the militia before April 1781 and served in the Continental Line sometime afterward. Their places of enlistment reveal that most of them came from one portion of the state. Nearly two-thirds of them enlisted in the northeast quadrant of North Carolina from the eastern boundary of Guilford County in a line directly eastwards towards the coast.[20]

Among the most interesting stories of men who served in both the line and militia are those of two men during the siege of Charleston. These men, with the knowledge that militia units were to be quickly paroled, assumed the role of militiamen. One man’s term ended in 1779 but he chose to stay in service only to be captured. He changed from his Continental uniform and attached himself to an Orange County militia unit. Another man’s term ran out during the siege and he joined an unidentified militia unit. While both were subsequently paroled, only one served a militia term afterward.[21]

“Other Free” Persons

Pension applications are mostly devoid of an applicant’s race or ethnicity, but free people of color did indeed serve in the militia and state troops during the war. Less than two percent of North Carolina militia pension applicants cross reference with “Other Free” or “Free Colored” persons listed in Federal Census data and contemporary rosters of free people of color.[22] It seems as though only a fraction of free men of color served in the militia compared to those that served in the North Carolina Line. Based on an initial review, free men of color who served solely in the North Carolina Line could represent more than five percent of all North Carolina Continentals.[23] There is, however, consistency on where these men enlisted. A majority of those who served in the militia and state troops, and in Continental service, entered in the northeastern part of North Carolina, where free people of color represented between four and eight percent of five northeastern North Carolina counties in 1790.[24] One northeastern county (Granville) had a relatively high number of free men of color in a local militia unit—almost seventeen percent were listed as non-white in complexion.[25] The lower percentage of free men of color in the militia and state troops is not readily apparent. The most straightforward conclusion may be that free men of color avoided militia service in North Carolina. Relatedly, it seems possible that many of these free men of color saw Continental service as more appealing and joined those units early in the war.

Prisoners of War

Over ten and a half percent of militia and state troop pension applicants noted being held prisoner at some point in the war. This figure is not surprising given that North Carolina soldiers were present at many actions such as Brier Creek, Charleston, Camden, Fishing Creek, and other engagements where American prisoners were taken. There are clear indications in pension applications of British soldiers recruiting American prisoners. One man, a prisoner at Charleston, was offered “$50 cash, a suit of Regimentals and a share of the Spoils or booty of the City” to join the British army.[26] Several American prisoners appear to have joined British units to better their conditions. These prisoners noted being “with” British units and then “deserting” them when the opportunity arose.[27] Two men recorded that they joined British service to be released from prison ships but later noted “escaping” from them.[28] There is at least one instance in pension applications of a British soldier deserting and joining the North Carolina militia. He later received a bayonet wound in action near Wilmington in 1781.[29]

Numerous pensioners reported guarding British and Loyalist prisoners. For some unknown reason, a few of these men felt it proper to note in their applications witnessing violence against enemy prisoners or perpetrating it themselves. One pension applicant initially felt remorse after witnessing the killing of Loyalist prisoners after the Battle of Pyle’s Defeat but changed his sentiments the next day when confronted by a young man lying on the road who had suffered a bayonet wound and was left for dead by the enemy.[30] Two brothers, serving together, noted in their applications capturing and killing the same Tory prisoner.[31] Another two men in separate incidents reported hanging a group of three and four Tories after capturing them.[32] One man was guarding a prisoner of the British Legion when another band of militia arrived, took the prisoner and executed him on the side of the road.[33] In perhaps the strangest incident in the reviewed pension applications, one man led his militia unit to his brother who was a Tory. His fellow militiamen were originally planning to kill the Tory brother but instead devised a plan of exchanging him for American prisoners. The Tory was successfully exchanged for American prisoners. The pension applicant recalled his brother was “absent one or two years”.[34]

Location of Pension Applications

Just as most pension applicants were not born in North Carolina an even higher percentage chose to leave the state in the years after the war ended. Over sixty percent of the pension applicants who served North Carolina during the war filed their claims outside the state.[35] The three states of Tennessee, Georgia, and Kentucky account for nearly forty percent of locations where applications were filed and about two-thirds of the all locations filed outside of North Carolina. Only two percent of applications were filed west of the Mississippi River. Just five men filed applications in northeastern states (Figure 8). The highest out of state application rates were of those that entered service in the western and northern counties of North Carolina. Conversely, relatively high portions of those who remained in the state after the war were in the southeastern counties of the state.

Conclusion

The men studied here represent only thirteen to sixteen percent of the men who served in the North Carolina militia or state troops during the war. It seems unlikely that we may ever know as much about the remainder, over eighty percent, and their war exploits as we know about the men studied here. However, coming away from this study it is apparent that there is much more to be known about how these North Carolina men compare with the militia of other states. For instance, were most of the men that served in the Maryland militia born outside the state like those of North Carolina? Or how many tours of duty did the men of the Massachusetts militia serve in comparison to North Carolina? These and many more questions present themselves when considering the data here in comparison to other states. Fortunately, the pension application data to answer these questions have been transcribed and made available online (or will be soon). The pension applications are there; their personal and collective stories are waiting to be told.

The author would like to thank Will Graves and C. Leon Harris for their insights on Federal Pension applications which form the basis of this work.

[1]J. D. Lewis, NC Patriots 1775-1783: Their Own Words, 1: vii.

[2]All Virginia state pension applications are also posted there along with some of those from South Carolina.

[5]Will Graves, “Pension Acts: An Overview of Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Legislation and the Southern Campaigns Pension Transcription Project”, Southern Campaigns Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters, revwarapps.org/

[6]David J. Hacker, “Decennial Life Tables for the White Population of the United States, 1790-1900.” Historical methodsvol. 43 no. 2 (2010): 45-79.

[7]As Continental soldiers generally served continuously, some for multiple years, and for much longer terms than those in the Militia, it felt prudent to exclude them from the narrative on length of service.

[8]3,300 men provided the terms of their service.

[9]Frederick Daniel, pension application R2646.

[11]Several other North Carolina slaves were freed by their wartime service but none of them appear to have filed a pension application.

[12]3,038 of the sample set provided their signature or “mark”. Of these, 1,617 provided their own written signature.

[13]F.W. Grubb, “Growth of Literacy in Colonial America: Longitudinal Patterns, Economic Models, and

the Direction of Future Research,” Social Science History Vol. 14 No. 4 (Winter, 1990), 451-482.

[15]Joseph Dobson (W19187), William Falls (S6834).

[19]448 men were identified as having served in the North Carolina Continental Line and a North Carolina the militia or state troop unit.

[20]Of the 448, 408 identified their place of residence when starting military service.

[21]Thomas Hale (S37975) and Jesse Rickertson (W27382).

[22]Eric Grundset, ed., Forgotten Patriots: African American and American Indian Patriots in the Revolutionary War (National Society Daughters of the American Revolution, 2008), 560-566. Fifty-nine total men identified, two were noted as being part or “full blood” Native American, four were noted as “mulatto.” The remaining were mostly identified in Census records as “Other Free.”

[23]If ten to fifteen percent of 8,800 North Carolina Continentals filed applications and seventy-two “free persons of color” have been identified this would amount to between five and eight percent of the total.

[24]Paul Heinegg, List of Free African Americans in the Revolution: Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware,.www.freeafricanamericans.com/introduction.htm

[25]Size Roll taken by Capt. Ralph Williams of Men enrolled in Granville County May 25th 1778 to fill the North Carolina quota of Continental Soldiers, revwarapps.org/b250.pdf.

[27]John Sims (W10252), Michael Nash (W4042), Joseph McPeters (W1303).

[28]William Poplin (W10231), John Hancock (R4551 & W10086).

[31]Amos Church (S8191), John Church (W3943).

[32]John Sawel (S4657), George Parks (W27457).

[35]3,696 applications note where the pensions were filed. 2,252 Pensions were filed outside of North Carolina.

16 Comments

Awesome! Looks like we had a mind meld at some point, because I’m working on a very similar project with New Jersey soldiers!

I’d be cautious about the literacy rate, tho’ – I started to tabulate which applications were signed and which weren’t, but going through the 1818 pensions made me rethink that.

In 1820, the pension law was reworked so that applicants would need to submit personal inventories proving their indigence, as well as the number of individuals in their household, which happened to include a description of their health.

A high number of Continental New Jersey veterans reported being infirm and suffering from the rheumatism – and in the 1820s, these men were “only” in their late 50s to early 60s.

By the 1830s, the surviving veterans are now considerably more aged – so that they may at one point have been literate enough to write their name, but had reached the point in their lives – their 70s and 80s – that they were more advanced in their infirmity that they were physically no longer able to do so.

Great stuff, tho’! Jealous you got to use the transcribed works from the pension projects. I had to transcribe all mine from scratch!

Jason, Thank for the comments. On the signatures, the transcribers often made notes about whether the pensioner’s “signature” matched handwriting of the person taking the statement. In those cases, I did not mark them as “literate”. You are correct that many men list their infirmities. It seems possible that many of them were at some point able to sign their names but couldn’t because of their age. I did struggle to include the literacy information in the work which I did with the caution noted.

I don’t think I could have undertaken this study without the transcriptions having been done. I could not imagine having to transcribe 9,000 applications.

Glad to see that someone is working on other states! Would love to compare notes!

Thank you, Douglas, for this very interesting article on militia demographics. And thanks to Will Graves and C. Leon Harris for their dedicated pension app work, which has proved quite useful to me in my own historical and genealogical research.

Regarding demographics, my 6th great-grandfather, Bailey Anderson (Pension Application S30826), served mostly in SC units, but also volunteered in units from VA (under Christian during the Cherokee campaign) and NC (under McDowell in summer 1780). After the war, he was an early settler of Kentucky (circa 1795), Indiana (circa 1805), and East Texas (1819), and filed his pension app, which he signed with a mark, in Natchitoches, LA. He was 79 (almost 80) when he submitted his pension app in 1833 (born in Stafford Co., Virginia, in November 1753).

Jay, thank you for the note. Bailey Anderson is represented in this study. A fair number of NC pensioners served in other states, mostly South Carolina and Virginia units. If a man served in an NC militia/ state troop unit they were included.

For my master’s thesis I examined North Carolinas black soldiers. About 480 of them are known, and roughly 120 left pensions. I did a similar demographic analysis of those men. To examine and crunch numbers for over 3,000, however, is an impressive feat! This work augments Hugh Rankin’s research on the Continental line very well.

Well done to Mr. Dorney! It is an excellent informational piece. Mr. Dorney’s comments and the results of his work also illustrate the enormous value of the work conducted by Mr. Graves, Mr. Harris and their colleagues which aids serious study of the ordinary soldier in the American Revolution. I turn to their work weekly in pursuit of my own research. They deserve a medal!

Greg, thanks for the note. It took me 10 months to collect the data from the transcribed applications. I think it would have taken me years having to review the original handwritten applications. I agree Will and Leon deserve some sort of recognition. I am indebted to them and the others that have transcribed these applications.

Thank you Douglas for the enlightening article on our military Patriots of NC.

It would be of further interest to ask whether your studies included any collections of comments in Pensions regarding the Declaration of Indepence, the actual purpose of our RevWar.

In James Collins Pension (W6737, Tempey) NC he states during his 1776 first (of three) militia tours that he “marched from the County of Bute … onto Wilmington … he was at Wilmington when the news of the Declaration of Independence was received there and recollects the rejoicing which that event received.”

GGGG Grandfather

Thanks for any comments from other Pensions. CGL

Charlene, Thank you for your comments. References to the Declaration in the pension applications I reviewed were few. It would be something rather quick to find out using the powerful search tools on pensions website. In checking my spreadsheet James Collins is there.

love the analysis and the rewarapps site. Sometimes when I’m bored, I take an an ancestor’s muster return and check to see how many I can find in the database. Always interesting reading and insights.

A very interesting article, and especially timely for me. I have been attempting to sort through southern pension records in an effort to sort out discrepancies in online genealogy sites concerning my family. This article has added more insight and dimension to my search. Thank you for your research, it may indeed help me with mine.

Mr. Dorney:

Any idea where I can look for the fate of an ancestor who fought at the battle of Camden in 1780? He was one Simon Edwards, a captain in the Jones County, NC militia. I can find no pension application for him, but two other pensioners mentioned that he was killed at the battle. Yet other records state that he died from smallpox while a British prisoner. Edwards’ June 1780 will was probated in December 1781 in Jones County, NC court by yet another ancestor Simon Speight but I am wondering if the time delay could be explained by the fact of uncertainty over Edwards’ fate or imprisonment. I will be trying to order “Relieve us of this burden : American prisoners of war in the revolutionary South, 1780-1782” by Carl P. Borick through interlibrary loan to check to see if Edwards is listed as a prisoner of war. Thanks for any suggestions or assistance you can provide in this quest.

Sincerely,

John F. Speight

John,

I could only find two sources for him. The most interesting is the one where he is reported as wounded at Camden and died of smallpox. Perhaps he was wounded, briefly captured, and left on the field of battle and later recovered. It seems unlikely there would have been an immediate prisoner exchange given the nature of the battle. And there is no first name, so we’d have to assume its Simon. See links below.

There is some letter correspondence of American doctors attending to prisoners in Camden. I don’t have it any longer but don’t recall it mentioning names specifically just that American prisoners were doing badly.

I’d recommend reading Borick’s book. Perhaps his source information might lead to some other sources. Having said that, NC militia records are scarce and almost never complete or legible. I’ve found only a very few pension records of men who died during the war. As he was an officer there are very likely some pay records, accounts documents, or rosters at the NC Archives in Raleigh. There are printed indexes but the actual info is on microfilm. Also in that building is the State Library that may have some printed rolls. A librarian or archivist there could surely help. It’s certainly worth a call to them. I believe Jones County is unlikely to have any records that they didn’t forward to Raleigh but would suggest a call to them too.

https://revwarapps.org/b282.pdf

http://revwarapps.org/b195.pdf

Doug Dorney

Please contact me if you have any other questions at do***********@ho*****.com

John,

I found one record that indicates Simon was wounded and died of smallpox after Camden. https://revwarapps.org/b282.pdf It likely is Simon and no mention of him being a prisoner. It seems possible that he was briefly a prisoner and then died in the squalid conditions of the Camden hospital. There are a few letters from an American doctor who attended the American prisoners in Camden but I don’t recall any specific prisoner names.

Borick’s book is one I’d recommend as there may be some sources in the notes that help with your search. I’d also recommend contacting the NC Archives if you have not done so. I’d be fairly confident there are pay accounts, receipts, etc. there from the militia unit. The state library is in the same building and there may be some militia rosters printed but don’t have any first hand knowledge of them.

Doug

do***********@ho*****.com

Lovely work! I am compiling a book on the patriots of Mecklenburg County, NC, in 1775. Most, if not all, continued to be in the militia in 1776 and beyond. I am pleased to find some of the statistics I was looking for in your work and will be citing some data with appropriate reference.

Years ago, I found a site that listed all the militia units, the officers, and the members. Did you work from such a list or would you know where I could find it? Thanks

Sue-

J.D. Lewis published several volumes of North Carolina Revolutionary War soldiers entitled NC Patriots: 1775-1783. These are available online via Google Books. Related to these are website called Carolana.com which has massive lists of NC militia soldiers. I believe that may be the site you mentioned.

To your question, no, I did not work from those lists since most didn’t file pension applications. I exclusively used the Southern Campaigns Pension Applications and Roster Website: revwarapps.com

I am submitting a manuscript to my publisher in the next few months. It will a greatly expanded book length version of this article but for the four southern states with demographic information from 8,500 soldiers.

The editor can provide my email address if you have any other questions.