Following the American surrender at Charleston on May 12, 1780, the Continental Army’s “Southern Department” was in disarray. Taken prisoner that day were 245 officers and 2,326 enlisted, including Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln, the Southern Department’s commander-in-chief, along with militia and armed citizens, the most American prisoners surrendered at one time during the American Revolution.[1]

That summer, scattered elements of the Continental Army regrouped in central North Carolina under command of Johann Kalb, the European officer and self-proclaimed “Baron de Kalb.” Earlier that spring, Kalb had been placed in charge of the first and second Maryland brigades, along with the Delaware Regiment and the 1st Artillery with eighteen field pieces—about 1,400 soldiers in all. Marching from Morristown, New Jersey, in mid-April, their mission was to relieve Charleston and serve as a nucleus for Southern militia. But arriving in central North Carolina in late June, Kalb found Charleston already surrendered and provisions and militia reinforcements scarce throughout the South.[2]

Meanwhile, the Continental Congress named Lincoln’s successor on June 13, picking Horatio Gates, the hero of Saratoga. By 1780, Gates was well-known for personality conflicts with his fellow officers, prominently Benedict Arnold and George Washington. But Gates’s political reputation, at least, had survived his conflict with Washington, and he was still well regarded for his rapport with the enlisted and volunteer militia. “Unlike most American generals,” Gates “had great confidence in short-term soldiers and showed a keen understanding of their temper,” writes his biographer. “It was his announced policy never to call up the militia until almost the very moment they were needed. Once they had finished their tour of duty, he was quick to thank them and to send them packing off to home.”

By June 1780, the now fifty-three-year-old Gates was on furlough from the Continental Army, convalescing at his Virginia estate. Washington had wanted Nathanael Greene for the southern command, but Congress wanted Gates, who was, after all, available and not far away. So Gates got the job.[3]

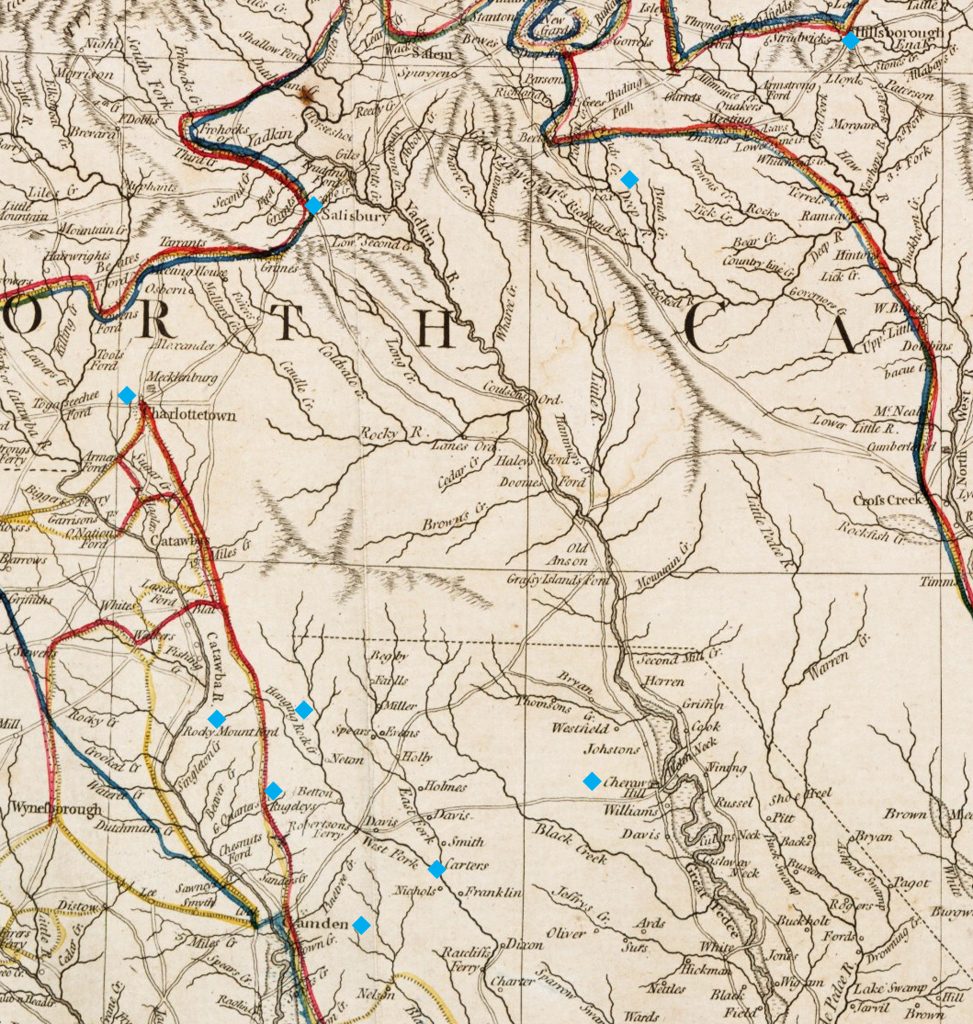

He joined Kalb on July 25, 1780, at Cox’s Mill on Deep River, in modern-day Randolph County, North Carolina, south of today’s Ramseur community. What happened next is perhaps a familiar tale, certainly one of the war’s most curious, with a narrative that goes something like this: Eager to repeat his heroics at Saratoga, Gates demanded an immediate and ill-conceived march directly toward the British Army stronghold at Camden, South Carolina, on a direct route through the Carolina’s infamously inhospitable “Pine Barrens.” In this haste, he ignored his cavalry and the assistance of Francis Marion, the famous South Carolina “Swamp Fox,” choosing to rely instead on untested militia, leading to a defeat of disastrous proportions at Camden on August 16, 1781, where Gates fled the field in eternal disgrace.

The framework of this version originates mostly from Otho Holland Williams, colonel of the 6th Maryland Regiment and Gates’s adjutant general, who provided many of its tenets in his “Narrative” of the 1780 campaign. Born to Welsh immigrants, Williams had joined the Frederick County rifle corps early in the war and steadily rose through the ranks. Henry Lee described him as “elegant in form . . . his countenance was expressive and the faithful index of his warm and honest heart.” But he did have his severe side. “He was cordial to his friends, but cold to all whose correctness in moral principle became questionable in his mind,” wrote Lee. Taken prisoner at Fort Washington in November 1776, he was promoted to colonel while still a prisoner at New York, then exchanged and served with distinction at Monmouth Courthouse. Prior to his service with Kalb, Williams had served briefly as Washington’s adjutant general, from December 1779 to April 1780.[4]

Williams’s narrative, at times, reads almost as a litany of Gates’s reckless and inscrutable behavior, including his orders “to march at a moment’s warning” (italics original) immediately upon taking command of the approximately 1,500 starving and ragged Continental soldiers assembled at Cox’s Mill (including elements of the Continental army who had escaped capture at Charleston and joined Kalb in North Carolina). Also, from Williams’s narrative we have a negative characterization of Gates’s decision to march toward Camden at night with militias and regulars that “had never been once exercised in arms together.” Gates, Williams reported, believed this ramshackle force consisted of seven thousand soldiers, though a field return revealed only 3,052. “These are enough for our purposes,” replied Gates cryptically, at least according to Williams’s account.[5]

Unpublished until 1822, when it appeared in William Johnson’s Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene, Williams’s version of Gates’s march frequently finds its way into contemporary American Revolution accounts, including the influential War of the Revolution by Christopher Ward and The Road to Guilford Courthouse by John Buchanan. But many of Williams’s aspersions were subsequently disputed by Thomas Pinckney, who served as Gates’s aide-de-camp during the Camden campaign. Pinckney’s narrative was written in response to Williams, and must be read in the context of a critical response, written over forty years after the events it described. Still, the two accounts differ sharply, with Williams’s version perhaps making for better storytelling, a tale of pride goeth before the fall at the expense of George Washington’s arch rival. But read in combination, they provide a more nuanced depiction of Gates’s strategy, especially when combined with other letters, documents, and critical analysis from the campaign.[6]

Prior to his arrival at Kalb’s camp, Gates had spent weeks in Virginia pleading for supplies and reinforcement from state and federal officials, including North Carolina governor Abner Nash and Virginia governor Thomas Jefferson. True, Kalb warned him, “I have struggled with a good many difficulties for Provisions” ever since arriving in North Carolina, but Gates apparently believed at least some of the assurances he had received from these officials, including one that “Articles of salt, rum, & c.,” would soon follow from the Continental magazines in Hillsboro. And Gates also anticipated supplies and reinforcements from North Carolina militia general. Gen. Griffith Rutherford, waiting for him at a forward position near Cheraw, on South Carolina’s Pee Dee River. Also marching toward Cheraw with 1,200 militia and “a plentiful supply of provisions” was former North Carolina governor Richard Caswell.[7]

According to Williams, Gates’s orders “to march at a moment’s warning . . . was a matter of great astonishment to those who knew the real situation of the troops.” By now wary of false promises, Kalb intended to march south on a westerly route, through the pro-Whig region around Salisbury and Charlotte, if he intended to march at all. To Williams fell the task of convincing Gates the countryside toward Cheraw was “by nature barren, abounding with sandy plains, intersected by swamps, and very thinly inhabited,” with a population hostile to the American cause, while the route through Charlotte was “in the midst of a fertile country and inhabited by a people zealous in the cause of America.”[8]

But this route would have taken Gates away from Cheraw, where the North Carolinians had promised him provisions. Pinckney suggested Gates’s route was chosen, essentially, due to the blackmail of Caswell and Rutherford, whose safety (and provisions) at Cheraw were threatened by nearby British forces. The only means of preserving Caswell and Rutherford “from defeat & destruction, was to form a junction as rapidly as possible,” wrote Pinckney. “Could Genl. Gates under these circumstances have retired to refresh his Army in summer quarters at Charlotte or Salisbury, leaving this body of Militia, the only hope of immediate support from the State in which he was acting, to be sacrificed by the imprudence or misconduct of their commanding Officer? Sound policy forbade it.”[9]

Also here is evidence of Gates’s militia strategy—that once embodied, militia must be used quickly, and toward expedient purpose. Historian Paul David Nelson believes Gates was stung by criticisms of the Saratoga campaign, where he had established a defensive position and won largely by capitalizing on British mistakes. “In the Carolinas he apparently intended to prove to his critics that he could be aggressive if he chose.” And probably also true was a Pinckney’s assertion that Gates believed the Continentals “may as well march on and starve, as starve lying” at Cox’s Mill.[10]

Whatever his rationale, Gates was resolute, assuring Williams “plentiful supplies of rum and rations were on the route, and would overtake them in a day or two,” probably referring to the Continental stores he’d been promised from Hillsboro. Williams deemed these assertions “fallacious” and “never . . . verified.”[11] Nevertheless, Gates set out for the Pee Dee River on July 27, just two days after his arrival, where starvation and deprivation soon followed. “At this time we were so much distressed for want of provisions, that we were fourteen days and drew but one half pound of flour,” recalled William Seymour, a Delaware sergeant, of his trip through the Pine Barrens. “Sometimes we drew half a pound of beef per man, and that so miserably poor that scarce any mortal could make use of it.”[12]

Gates had left most of his cavalry behind, a decision Continental officer Henry Lee described as his “Fatal Mistake,” for the “plains of Carolina,” with their wide fields and mature forests, were perfectly suited to cavalry operations.[13] When Gates arrived at Deep River, his only cavalry at camp were the remnants of Casimir Pulaski’s dragoons, now under command of the French officer Charles Armand. The Southern Department’s other cavalry regiments, under command of Anthony White and William Washington, had been decimated at Charleston and were refitting near Halifax, Virginia.

Lee’s criticisms, however, overlook the fact Gates did order White to join him in a letter dated July 20. But when White responded on July 26 that he had “only twenty horses fit for duty,”[14] Gates rescinded his orders, requesting instead that White join him only when his cavalry “are equipp’d for Service.”[15] Still, Williams’s assertion that “General Gates did not conceal his opinion, that he held cavalry in no estimation in the southern field,” suggests Gates did underestimate the cavalry’s role, which hadn’t been of much consequence in the fighting at Saratoga.[16]

More easily defensible is Williams’s insinuation that Gates ignored the assistance of Francis Marion. In Williams’s account, Marion joined Gates and his Continentals on their march south “attended by a very few followers, distinguished by small black leather caps and the wretchedness of their attire; there number did not exceed twenty men and boys.” This appearance, Williams wrote, “was in fact so burlesque, that it was with much difficulty the diversion of the regular soldiery was restrained by the officers.”

Williams reports Gates was “glad of an opportunity of detaching Colonel Marion” after receiving a request from the Williamsburg District in eastern South Carolina for a Continental officer to command their militia.[17] Indeed, Marion was the perfect man for the job, but at the least, Williams distorts the timeline of these circumstances, if not their broader implications. Marion biographer Hugh Rankin reports Marion joined Gates sometime around July 27 and did not leave him until August 14 or 15, right before the battle at Camden. Williams admits Gates ordered Marion to “watch the motions of the enemy, and furnish intelligence,” but clearly he implies Gates saw little value in Marion or his men.[18]

After arriving at Masks Ferry on the Pee Dee River on August 3, Gates was reinforced by one hundred Virginia state troops under Lt. Col. Charles Porterfield. But Gates was furious to discover Caswell had left Cheraw and was now marching toward the British position on Lynch’s Creek. To Williams, Gates declared “it appeared to him, that Caswell’s vanity was gratified by having a separate command—that probably he contemplated some enterprise to distinguish himself, and gratify his ambition.” But anticipating Williams’s opinion they should now turn west toward Charlotte, Gates argued it was now “more necessary to counteract the indiscretion of Caswell, and save him from disaster.” Surely, the Continental provisions Caswell possessed were part of this necessity.[19]

Gates also argued “having marched thus far directly towards the enemy, a retrograde or indirect movement, would not only dispirit the troops, but intimidate the people of the country.” Indeed, the propaganda effect of Gates’s march is widely overlooked in latter histories. Though he failed to find Caswell at the Pee Dee, Gates did issue there on August 4 a proclamation announcing to the people of the region the approach of his “numerous, well-appointed, and formidable army,” which would soon “compel our late triumphant and insulting foes to retreat from the most advantageous posts with precipitation and dismay.”[20]

Pure propaganda, but the proclamation electrified the countryside—evidence the hero of Saratoga still possessed his common touch. After it, “the spirit of revolt, which had been hitherto restrained by the distance of the continental force now advancing to the southward, burst forth into action,” reported Loyalist officer Charles Stedman, Cornwallis’s commissary officer. “Almost all the inhabitants between Black River and Pedee had openly revolted and joined the Americans.” Similarly, Banastre Tarleton reported Gates’s “name and former good fortune re-animated the exertions of the country.”[21]

Meanwhile, British Lt. Col. Francis, Lord Rawdon, commanding northern South Carolina from his headquarters at Camden, had ordered the 71st Highlanders to evacuate their outpost at Cheraw and retreat to a defensive position on Lynches Creek at Caswell’s approach, sending forward Lt. Col. James Webster and the 33rd Regiment to support their withdrawal.[22] “This the active incendiaries of the enemy represented as an act of fear and so encouraged the disaffected and terrified the wavering that the whole country between Pedee and Black River openly avowed the principles of rebellion,” Rawdon admitted in a letter to Cornwallis.[23]

Sensing opportunity in this disruption, Patriot partisans Thomas Sumter and William R. Davie attempted a coordinated attack against the British outposts at Hanging Rock and Rocky Mount on August 1. Rocky Mount was a heavily fortified outpost on the west side of the Catawba River. Hanging Rock, however, was an open camp, guarding the strategic road connecting Camden to Charlotte and the Waxhaw settlements.

Though Sumter’s primary attack against Rocky Mount was repulsed, Davie’s diversionary attack on Hanging Rock was a sparkling success. Surprising a Loyalist regiment on the outskirts of camp, Davie routed them with his dragoons, then vanished into the countryside with sixty horses and “one hundred muskets and rifles” before the remainder of the British camp could even beat to arms.[24]

Nothing in the historical record suggests Sumter and Davie were coordinating strategy with Gates at this time. Indeed, Rawdon reported to Cornwallis on August 2 “the enemy are moving about me but, as far as I can see, not with any combined plan.”[25]But Sumter, in particular, was a gifted intelligence officer, who actively sought strategic advantage in the turmoil caused by Gates’s approach.

And Sumter’s intelligence reports were already impacting Gates. Back on July 17, Sumter sent a letter to Kalb proposing an attack on the Santee River crossings at Nelson’s and Manigault’s ferries, suggesting it would require not more than “one thousand or fifteen hundred Troops.” This rearguard action, Sumter argued, would not only cut off Camden’s supply lines from the south, but also potential reinforcements, leaving Rawdon isolated and vulnerable to attack. It was a bold plan, uniquely suited to Sumter’s expertise, the hit-and-run militia raid. Kalb had handed the letter to Gates upon his arrival at Deep River on July 25, and clearly it influenced Gates’s later strategies.[26]

On August 6, Gates was still at the Pee Dee when he received correspondence that Caswell “had every reason to apprehend an attack on his camp” by the British forces at Lynches Creek.[27] Ordering his troops forward as soon as possible, Gates and Williams raced ahead to Caswell’s camp, where they found evidence of the provisions Gates had long believed Caswell possessed. After arriving, they were “regaled with wine and other novelties,” recalled Williams, though he found the camp strangely disorganized, which he attributed to Caswell’s efforts to “divest himself then, of his heavy baggage,” forced by the death of several horses and the “breaking down of carriages” on his march. Still, the long-delayed junction with Caswell “enlivened the countenances of all parties,” though the Continental troops “still subsisted upon precarious supplies of corn meal and lean beef, of which they often did not receive half a ration per day, and no possibility existed of doing better.”[28]

Meanwhile, Rawdon also raced toward Lynches Creek to reinforce the 33rd and 71st regiments, his object “to retard the progress of Gates . . . or to reduce the enemy to hazard an action where my peculiar advantages of situation would compensate for my disparity in numbers.” In all, his collected force totaled 1,100 men, “all regulars and provincials.”[29]

But Sumter “still menaced that road to Camden with a corps of militia,” and soon after arriving at Lynches Creek, Rawdon received word the enterprising Sumter and Davie had made another surprise attack on Hanging Rock on August 6. British Provincial and militia casualties were estimated at two hundred, while the American casualties were only fifty-three. But the camp was saved after American looting allowed the British forces to reorganize.[30]

Rarely depicted in the context of Gates’s march toward Camden, Sumter and Davie’s assault on Hanging Rock had the effect of a coordinated attack to Rawdon and his junior officers. “It appeared a clear consequence that Sumpter, whose men were all mounted, would lose no time in pushing for Camden,” Rawdon later recalled. “I addressed the Officers around me, who seemed struck with the obvious magnitude of evil. I told them . . . that we were in a scrape from which nothing but courage could extricate us, & that we must march instantly to crush Sumpter before he could further co-operate with Gates.”[31]

Rawdon retreated toward Camden, but learned the following morning Hanging Rock had been saved, diminishing his fears of a Sumter raid. Rawdon now ordered his men to establish a defensive position at a strategic causeway on Little Lynches Creek, a location he later described as “impenetrable” due to the surrounding swamp, “except where a causeway has been made at the passing-places on the great road.”[32]

Meanwhile, Gates and Caswell now marched toward Camden, finding Rawdon’s position at the Little Lynches Creek causeway too strong to attack when they arrived there on August 11. Gates now turned his army north, marching around the swamps of Lynches River toward Hanging Rock, where he could approach Camden from the main road. Williams suggested he should have detoured even farther north, to the Waxhaws, where he could feed and rest his army, though even he admitted such a “movement would look like retreating from the enemy.”[33] As Gates marched north, Rawdon withdrew toward Camden, where he collected most of his detachments and awaited reinforcement from four companies of light infantry sent from the British garrison at Ninety Six.[34]

Ever industrious, and with his forces swelling after the successful attack on Hanging Rock, on August 12 Sumter sent Gates a detailed report of British troop movements and assured him that Camden was “altogether defenseless . . . if Gen’l Gates, thenk proper to Send a Party over pinteree Creek to fall in their Rear . . . it Woud Totally Ruen them, and Nothing is more Certain then that their Retreat woud be Rendered exceedingly precareous.” This was another version of the plan Sumter had sent to Kalb in July—to cut off Camden from the south and west, rendering it vulnerable to siege or attack by a superior force, forcing Rawdon to either retreat or attack under unfavorable circumstances.[35]

After a detour of thirty-four miles, Gates and his army arrived on August 14 at Rugeley’s Mill, a small settlement about twelve miles north of Camden. That same day he was joined by approximately seven hundred soldiers under Gen. Edward Stevens, a former Continental Army officer now commanding Virginia militia.[36]

Gates’s bogus belief in his numerical superiority, therefore, became motivation for his foolish expedience in marching toward Camden in the dark, at least according to canon narrative. “On August 15, Gates ordered a night march which he expected would bring his army into position to trap a much smaller British force,” wrote historian Robert Middlekauff in The Glorious Cause. “Gates’s haste for battle had led him into a deadly predicament, a snare that he only began to comprehend on August 15,” agrees historian John Ferling in Almost a Miracle.[38]

Many of these histories further castigate Gates for his decision to send Sumter a hundred of his precious Maryland Continentals, along with three hundred North Carolina militia and two artillery pieces, with orders to intercept all stores and troops at the Wateree River headed for Camden. These precious resources would have been invaluable in the battle to come, argues historian John Buchanan, who calls it yet “another foolish decision.”[39]

But these criticisms are based on an assumption that it was Gates’s intention to attack, as Williams insinuated. From Thomas Pinckney’s narrative, we have a conflicting account, indicating the purpose of the nighttime march was only to establish a strong position seven miles north of the town. From this location, Gates would be “so near him [Rawdon] as to confine his operations, to cut off his supplies of Provisions . . . to harass him with detachments of light troops & to oblige him either to retreat or to come out & attack us upon our own ground, in a situation where the Militia . . . might act to the best advantage.”

Pinckney recalled Gates sent forward two officers, one an engineer, likely on August 14, “to select a position in front,” and upon their return, they reported “they had found a position . . . with a thick swamp on the right, a deep Creek in front & thick low ground also on the left” that could be fortified well enough “with a Redoubt or two & an Abbatis.”[40]

Supporting Pinckney’s version is an account from European officer John Christian Senf, who claimed he attended a council of Gates’s officers the afternoon of August 15 to discuss “taking another position for the Army, as the Ground where they were upon was by no means tenable. On reconnoitering, a Deep Creek,[41] 7 miles in front, was found impassable 7 miles to the Right, & about the same distance to the left, except only in the place where the Ford intersects the great road.” By marching there, Senf recounted, Gates’s army “would get a more secure Encampment, come nearer Genl. Sumpter, occupy the road on the East side of the Wateree river, and would be able to get nearer intelligence of the Enemy.”[42]

From this perspective, Sumter’s rearguard attack becomes part of a coordinated strategy to isolate Rawdon, not a foolish diversion of indispensable troops and artillery. And Francis Marion also may have played an important role in this plan. Despite Williams’s assertions Gates was “glad of an opportunity of detaching” the “burlesque” Marion into the South Carolina interior, it was only on August 14 or 15 that Gates sent Marion south, with orders to “go Down the Country to Destroy all boats & Craft of any kind” in order to prevent British troops from escaping Camden.[43]

With Sumter and Marion menacing British supply lines from behind, Rawdon would be forced to either attack Gates at his defensive position or retreat. Though his defenses at Camden were stout, Rawdon’s force was inferior to Gates, with about “1,400 fighting men of regulars and Provincials,” along with four to five hundred militia and North Carolina refugees. Also inside Camden were almost eight hundred sick or invalid soldiers deemed unfit for combat.[44] Indeed, Rawdon would later admit his plan was to “wait till my spies should apprize me of Gates’s being approached within an easy march, when I meant to move forward & attack him.”[45]

But if Gates’s plan was to set up a defensive position tempting Rawdon into attack, why wasn’t Williams notified? “It is possible that Col. Williams, who does not mention it, may not have known the transactions,” reported Pinckney, “but I have the most perfect recollection of it.” A perfect recollection shared by Senf and also Gates’s aide, Maj. Charles Magill, who recalled discussing the movement of the Army “to an advantageous post with a swamp in our front, fordable only at the Road” at a council of officers on the evening of August 15.[46] Referring to Williams’s quote that Gates deemed the number of troops “enough for our purpose,” Pinckney believed this was in reference only to the effort to establish a strong defensive position north of town, not in reference to a nighttime attack, as Williams insinuated.[47]

Here, then is perhaps the true mystery of the mysterious march of Horatio Gates, for Williams’ clearly depicts an officer corps afflicted with “animadversion” by Gates’s plans, his narrative describing men who “could not imagine how it could be conceived” the American forces “could form columns, and perform other maneuvers in the night, and in the face of an enemy.”[48]

Was Williams referring only to Gates’s decision to march at night? Gates’s biographer attributes that decision to Gates’s “need to reach his expected area of fortification hastily and secretly.” Senf reported that, at the council of officers, “It was Unanimously agreed upon to march that Night the Army to that Creek, by which means they would get a more secure Encampment.”[49] William R. Davie attributed Gates’s primary mistake not to the nighttime march, but to his failure to secure the forward position earlier in the day with “2 or 3 pieces of artillery” and light troops, who could scout British movements.[50] Pinckney’s editor, Robert Scott Davis, suggests Williams was not present at the meeting he recounted so vividly in his “Narrative,” but only reported the accounts of others.[51] If so, it seems odd Williams was not included, or not informed of the council’s assent to Gates’s plan.

Like any organization, the Continental Army had its factions. Having served on George Washington’s general staff almost five months as adjutant general, Williams was well aware of Gates’s feud with Washington. Were these rivalries the inspiration for the critical nature of Williams’ “Narrative”? Impossible to say. Certainly, among Gates’s many shortcomings during the Camden campaign, his failure to effectively communicate was one of them, though it is not hard to imagine Williams was predisposed to a bias against Washington’s arch rival. But here is one mystery about the mysterious march of Horatio Gates we can never solve, only attempt to put in context.

And though Rawdon was outnumbered, his position at Camden threatened by Sumter and Marion on his flanks and rear, he had an ace up his sleeve—Cornwallis. Becoming more and more concerned about the dispatches he was receiving from Rawdon and his northern outposts, Cornwallis decided to assume command of the Camden forces himself, and set out for the town from his Charleston headquarters early in the morning of August 14. “The British General approached rapidly, & I believe with only his personal escort,” recalled Pinckney, somehow escaping the reconnaissance of Marion, “expressly instructed for that purpose.”[52]

Arriving at Camden the next day, Cornwallis agreed with Rawdon’s assessment to either attack or retreat, though in retreat he “clearly saw the loss of the whole province, except Charlestown, and of all Georgia except Savannah.” With Sumter advancing down the Wateree, Cornwallis feared his “supplies must have failed me in a few days.” And so, “seeing little to lose by defeat and much to gain by a victory,” he resolved to attack, serendipitously ordering his army to “march at 10 o’clock on the night of the 15th” toward Gates’s position, his plan “to attack at day break.”[53]

For Gates, it was a devastating stroke of bad luck. By sheer coincidence, both armies marched toward one another at almost the same time, around ten o’clock the evening of August 15, Gates marching south, presumably toward the position identified in Senf’s memoir, Cornwallis on the same road heading north toward Rugeley’s Mill. “If the American Army had marched from Rugeley’s two hours earlier, or Cornwallis had moved from Camden two hours later, the event of the contest would probably have been very different,” conjectured Pinckney. “But the meeting in the night was one of those incidents frequently occurring in War, which so often defeats the best combined arrangements.”[54]

Destiny, it seems, was leading Horatio Gates and his impoverished, hungry army toward conflict with a foe not superior in number, but superior in discipline and experience. The Battle of Camden would be fought the following morning, on August 16, 1780, after the two armies collided in the night, skirmished, then formed for combat. And it was a destiny that would lead not only to the demise of Gates’s military career, but also the eternal destruction of his historic legacy, for the adversities of Gates’s “mysterious” march foreshadowed a fate even worse in the battle to come.

[1]Mark M. Boatner, Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (New York: David McKay Company), 213

[2]Christopher Ward, War of the Revolution (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2011), 714.

[3]George A. Billias, “Horatio Gates: Professional Soldier,” from George Washington’s Generals and Opponents (New York: Da Capo Press edition, 1994), 88-100.

[4]Boatner, Encyclopedia, 1208-1209; Henry Lee, The Revolutionary War Memoir of General Henry Lee (New York: Da Capo Press edition, 1998), 593, and John Beakes, Otho Holland Williams in the American Revolution (Charleston, SC: Nautical & Aviation Publishing Co., 2015), 59-60.

[5]Otho Holland Williams, “A Narrative of the Campaign of 1780,” in William Johnson, Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene: Major General of the Armies of the United States, Vol. 1 (Charleston, SC: A.E. Miller, 1822), 485-510.

[6]According to Pinckney’s editor, Robert Scott Davis, Jr., Pinckney’s narrative was first published in Historical Magazine in 1866, and not reprinted in its entirety until Davis’s edited version in 1985.

[7]Baron De Kalb to Horatio Gates, July 16, 1780; Millett & Estis to Gates, July 22, 1780; Griffith Rutherford to Gates, July 30, 1780; Richard Caswell to Gates, July 30, 1780, all in The State Records of North Carolina (Goldsboro, NC: Nash brothers, 1886-1907), 14: 503, 508, 514, 515-516 respectively. Quote about Caswell’s “plentiful supply of provisions” is from Williams, “Narrative,” 486.

[8]Williams, “Narrative,” 486-487.

[9]Thomas Pinckney, “General Gates’s Southern Campaign,” July 27, 1822, appearing in Robert Scott Davis, Jr., “Thomas Pinckney and the Last Campaign of Horatio Gates,” The South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 86, No. 2 (April 1985), 94-96.

[10]Paul David Nelson, General Horatio Gates: A Biography (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1976), 222; Pinckney, “General Gates’s Southern Command,” 94.

[11]Williams, “Narrative,” 486-487.

[12]William Seymour, A Journal of the Southern Expedition, 1780-1783 (Wilmington, DE: The Historical Society of Delaware, 1896), 4.

[13]Henry Lee, Revolutionary War Memoirs, 171-172.

[14]Gates to Anthony White, July 20, 1780, Nelson, General Horatio Gates, 226; White to Gates, July 26, 1780, State Records of North Carolina, 14: 510-512.

[15]Gates to White, August 4, 1780, Nelson, General Horatio Gates, 227.

[16]Williams, “Narrative,” 506.

[18]Ibid., 482; Hugh Rankin, Francis Marion: The Swamp Fox (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1973), 56-58.

[19]Williams, “Narrative,” 488-489.

[20]”Proclamation Issued by Horatio Gates at Pedee, the 4th of August 1780,” in Banastre Tarleton, A History of the Campaigns of 178 and 1781, in the Southern Provinces of America (London: T. Cadell, 1787), 140-141.

[21]Charles Stedman, The History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War (London, 1794), 2: 200 and 205; Tarleton, Campaigns, 97.

[22]Francis Rawdon to Charles Cornwallis, July 31, 1780, The Cornwallis Papers: The Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Theatre of the American Revolutionary War, Ian Saberton, ed. (Uckfield, UK: The Naval & Military Press Ltd, 2010) Volume 1, 223 (CP).

[23]Cornwallis to Lord George Germain, August 20, 1780, in Jim Piecuch, ed., The Battle of Camden:A Documentary History(Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2006), 52; Rawdon to Cornwallis, July 31, 1780, CP, 1: 223.

[24]William R. Davie, The Revolutionary War Sketches of William R. Davie (Raleigh, NC: N.C. Dept. of Cultural Resources), 11-12.

[25]Rawdon to Cornwallis, August 2, 1780, CP, 1: 228.

[26]Thomas Sumter to Johann Kalb, July 17, 1780, in Michael C. Scoggins, The Day It Rained Militia (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2005), 134-135; George A. Billias, “Horatio Gates: Professional Soldier,” 82.

[27]Williams, “Narrative,” 489.

[29]Francis Rawdon, “Account of the Battle of Camden,” January 19, 1801, in Piecuch, ed., Battle of Camden, 58.

[30]William R. Davie, Revolutionary War Sketches, 13-14; John Buchanan, The Road to Guilford Courthouse (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1997), 133-137.

[31]Rawdon, “Account of the Battle of Camden,” 58.

[33]Williams, “Narrative,” 490.

[34]Charles Stedman, History,2: 204.

[35]Sumter to Thomas Pinckney, August 12, 1780, The State Records of North Carolina, 14: 553-554; Williams, “Narrative,” 492, and Joseph Graham, General Joseph Graham and His Papers, William A. Graham, ed. (Raleigh, NC: Edwards & Broughton, 1904), 241.

[36]Ward, War of the Revolution, 721.

[37]Williams, “Narrative,” 492-493.

[38]Robert Middlekauff, The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), 455; John Ferling, Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 441.

[39]Buchanan, The Road to Guilford Courthouse,155.

[40]Pinckney, “General Gates’s Southern Campaign,” 84-86.

[41]Reported as Sanders Creek in Piecuch but Granny’s Creek elsewhere.

[42]John Christian Senf, “Extract of a Journal concerning the Action of the 16th of August,” in Piecuch, ed., The Battle of Camden, 22-23.

[43]Hugh F. Rankin, Francis Marion, 58. Quote is from, Peter Horry to Nathanael Greene, April 20, 1781.

[44]Cornwallis to Germain, August 21, 1780, CP: 2: 12.

[45]Rawdon, “Account of the Battle of Camden,” 60.

[46]Charles Magill to his father, n.d., in Piecuch, ed., The Battle of Camden, 43.

[47]Pinckney, “General Gates’s Southern Campaign,” 86-87.

[48]Williams, “Narrative,” 493; Senf, “Extract of a Journal,” 23.

[49]Nelson, General Horatio Gates, 230; Senf, “Extract of a Journal,” 23.

[50]Davie, Revolutionary War Sketches, 17.

[51]Robert Scott Davis, “Thomas Pinckney and the Last Campaign of Horatio Gates,” 78.

[52]Pinckney, “General Gates’s Southern Campaign,” 91.

6 Comments

An excellent prelude to the Battle of Camden. Given the circumstances, Gates can certainly be forgiven for marching so quickly into South Carolina. His major miscalculation was the failure to have scouting parties as far toward Camden as possible. If indeed he intended to wait and have the British attack them he would have then had the problem of the militia deserting him. It also seems possible that a defensive position by Gates may have resulted in his position being besieged given his lack of cavalry. It is interesting to question whether Daniel Morgan’s presence in Gates’s army would have resulted in a different outcome.

Good article. But right off the bat this struck me: “Taken prisoner that day were 245 officers and 2,326 enlisted, including Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln, the Southern Department’s commander-in-chief, along with militia and armed citizens, the most American prisoners surrendered at one time during the American Revolution. ” At the disastrous surrender of Fort Washington… the Americans had 59 killed, 96 wounded casualties, and 2,838 men captured. Maybe the mentioned but unaccounted number of “militia and armed citizens” put the Charleston numbers over the top?

Hi Ed,

You are correct that the author’s total only includes the Continentals. If you add in the militia captured the total losses at Charleston were about 5,600. See note 143 on page 315 of “The Southern Strategy” for a detailed breakdown.

-Dave

Excellent narrative and analysis. Thank you for enlightening me through Senf’s account of the council of war. It makes sense that Gates was looking to have his grand army fight a defensive rather than open battle. I have an ancestor who fought with William Smallwood’s Maryland Continentals and was captured in the Camden disaster and this is campaign is of great interest to me. Wonderful read.

Agree quite well written. I also think that Pinckney’s narrative is an underutilized resource compared to Williams’. The historiography of the era is still heavily influenced by the Washington-Gates rivalry. That said, while Pinckney’s narrative removes much of the “mystery” from Gates’ supposed mad dash into South Carolina, it does not exonerate him from the mistakes he made that resulted in the loss of his army.

Replying to Ed Wimble: The total number of American soldiers captured at Charleston in 1780 was about 5,600 including both Continentals and militia.

Finally, someone gets it right, or nearly so! It’s particularly good that the author notes the need for Gates to concentrate his forces by going toward Cheraw, since the North Carolina forces there had not obeyed Gates’s orders for them to come to him. There is also the point that Gates was under orders to get into South Carolina as soon as possible, as a Rebel presence there was thought to help in some secret efforts which Congressional agents were making to bring Spanish troops openly into the South. (There’s a letter to this effect from Richard Peters, Secretary to the Board of War, in the Gates Papers.)