The American Revolution changed the way Americans viewed one of the world’s great tragedies: the African slave trade. The long march to end the slave trade and then slavery itself had to start somewhere, and a strong argument can be made that it started with the thirteen American colonies gaining independence from Great Britain, then the world’s leading slave trading country.

Typically, with great movements, there is no direct line of progress. More often, progress is like a wave, moving forward, but then receding somewhat. That describes the progress on the antislavery front in the United States—during the years of the Revolution, there was definite progress, progress which ebbed in the years immediately following the Revolutionary War. Still, some progress had been achieved: by the early 1800s, each Northern state had either prohibited slavery or provided for gradual emancipation, and American participation in the African slave trade was formally banned in most states after the Revolutionary War and in all states by 1808. Tragically, the American Revolution did not end slavery in the South. It would take a Civil War and hundreds of thousands of deaths to end the institution in 1865.

In the first three quarters of the eighteenth century, Great Britain was the leading slave trading country in the world. By the 1770s, each year, on average, British merchants from Liverpool, Bristol, London, and smaller ports sent ships to the coast of West Africa, purchased more than 45,000 captives, and transported them across the Atlantic Ocean, mostly to British possessions in the Caribbean, such as Jamaica and Barbados.[1] There, the African captives worked in horrible conditions on sugar cane plantations, suffering a high death rate from overwork, abuse, and disease.

In the course of four centuries British merchants carried an astounding number of Africans across the Atlantic, estimated at 3,250,000. Taking into account the years 1501 to 1867, when the last slave ship crossed the Atlantic to Cuba, merchants sailing from Great Britain outfitted an estimated thirty-one percent of all slave voyages even though their participation in the trade was stopped by legislation in 1807.[2] Still, that placed them second to the Portuguese, who carried more than 5,800,000 African captives in the Middle Passage, mostly to Brazil. They began a few hundred years earlier than the British, in the 1400s, and ended decades after Britain’s 1807 prohibition.

The merchants of what would become the United States played a comparatively small role in the African slave trade. From 1501 to 1860, mainland North American colonial and, later, United States merchants carried an estimated 305,000 slaves across the Atlantic, and outfitted about two and a half percent of the slaving voyages.[3] In the twenty-five-year period from 1751 to 1775, however, North American ships accounted for between four and five percent of the slaving voyages. The colony of Rhode Island sent more than one-half of the slave trade voyages from North America, with New York and Boston also sending ships on long voyages to the West Africa coast.[4]

Comparatively few of the captive Africans carried across the Atlantic Ocean were landed on North American mainland shores. Of the approximately 12,500,000 slaves forced across the Atlantic by Europeans and Americans, fewer than 400,000—just over three percent of the total—were disembarked in what would become the United States. The Caribbean, where sugar cane plantations fueled the insatiable demand for sugar, and South America (mostly Brazil) accounted for ninety-five percent of the captives brought from Africa.[5]

The half-decade leading up to April 1775, when armed hostilities broke out at Lexington and Concord, was a particularly idealistic time in what would become the United States. Whig supporters spouted the rhetoric of freedom from Great Britain and personal liberty for themselves. This strong passion for freedom and liberty spilled over to result in the first organized national movement to end the slave trade in American history. But before that happened, disparate protests in various colonies had to arise. The conviction that the slave trade and slavery itself were completely wrong took time for most white Americans to realize. Race-based African slavery had existed in the Western world since the mid-fifteenth century, and national movements to achieve humanitarian ends were not yet known in the Western countries. Slowly, some voices became louder and more strident in opposing the slave trade and even the institution of slavery itself. This process was unquestionably accelerated by the American Revolution.

As historian David B. Davis has written, “By the eve of the American Revolution there was a remarkable convergence of cultural and intellectual developments which at once undercut traditional rationalizations for slavery and offered new modes of sensibility for identifying with its victims.”[6] The process was advanced by increasing capitalism: as free labor became more common, other labor means—indentured servitude, debt bondage, and slavery—came increasingly to appear antiquated and anomalous. White laborers in particular did not want to compete in the workplace against enslaved persons. Enlightenment ideas about human equality and shared human nature also played an important part in this process, as did the rapid growth of evangelical Christianity.

The American Revolution itself was a key catalyst to antislavery thought. With American colonists declaring their beliefs in “liberty” and “natural rights” and denouncing a British plot to “enslave” them by taxing them without representation, it is not surprising that some were moved to question the plight of those whom the colonists themselves had actually enslaved. After all, at this time around twenty percent of the population of the thirteen colonies consisted of Blacks, most of them enslaved persons treated as mere property. Historian W. E. B. DuBois put it more bluntly: “the new philosophy of ‘freedom’ and the ‘rights of man,’ which formed the cornerstone of the Revolution, made even the dullest realize that, at the very least, the slave-trade and a struggle for ‘liberty’ were not consistent.”[7]

In North America, political opposition to slavery began within the Society of Friends, or Quakers. Founded in England in the seventeenth century, Quakerism was a radically egalitarian creed that led many in the Society to question the morality of slave trading and slavery. By the start of the Revolutionary War, most Quaker meetings in the thirteen colonies had prohibited their members from holding enslaved persons.[8]

After struggling to eliminate slavery within their own ranks, by 1774 Quakers began trying to persuade others of its immorality, but they hardly represented general public opinion in the colonies. For the dual slave institutions—importation of slaves and the use of slave labor—to be attacked successfully, mainstream religious sects and other groups would have to raise their voices in protest. As historian Joanne Pope Melish notes, “it was only in the context of the Revolution that the antislavery movement gained support outside a fringe group of Quakers and other agitators.”[9]

The first Congregationalist minister to come out publicly against slavery was perhaps Samuel Hopkins, a Connecticut native who in 1770 moved to Newport, Rhode Island, to become pastor of the First Congregational Church. Hopkins began to preach against the slave trade in the very town most implicated in it. He published an influential pamphlet railing against the slave trade in 1776. Calling the trade “a scene of inhumanity, oppression, and cruelty, exceeding everything of the kind that has ever been perpetrated by the sons of men, ” Hopkins painted with words vivid scenes of war, death and destruction along the coast of Africa, on the purchases at the seaports, the brandings, the terrors of the Middle Passage, the uncounted deaths from the process of acclimatization, and the brutal whippings.[10] Most of the slave traders in Newport, however, belonged to the Second Congregational Church, the Anglican Church, and other religious groups. Still, Hopkins and one other religiously-inspired antislavery leader, the Quaker Moses Brown, became active in trying to persuade the Rhode Island General Assembly to limit the slave trade.

One of the most widely-read pamphlets and sermons prior to the outbreak of war in 1775 was an “Oration” titled in part the Beauties of Liberty, published in 1772 and thought to have been written by the Rev. John Allen, a Baptist minister in Boston who would die prematurely in 1774 at the age of thirty-three. In his sermon Allen defended American rights, including the burning of the British revenue cutter Gaspee in Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island earlier in 1772. But in the published edition he added as an addendum a scorching criticism of the slave trade and slavery. Allen railed, “for mankind to be distressed and kept in slavery by Christians, by those who love the gospel of Christ; for such to buy their brethren (for of one blood he has made all nations) and bind them to be slaves to them and their heirs for life. Be astonished, ye Christians, at this!” Moving on to the horrors of the slave trade, Allen wrote powerfully, “for Christians to encourage this bloody and inhuman trade of man-stealing, or slave-making, oh how shocking it is!”[11]

In Connecticut, a few Congregationalist ministers began to publish provocative antislavery pieces. Jonathan Edwards, Jr., the son of the famous minister by the same name and pastor of the New Haven Congregational Church, published several anonymous antislavery pieces in New Haven newspapers in the fall of 1773 and early 1774. In 1774 the Rev. Levi Hart, a trustee of both Yale and Dartmouth Colleges, delivered an important sermon in Connecticut (published the next year) that attacked the slave trade and slavery as a moral evil. “What have the unhappy Africans committed against the inhabitants of the British colonies and islands in the West Indies,” Hart asked, “to authorize us to seize them, or bribe them to seize one another, and transport them a thousand leagues into a strange land, and enslave them for life?”[12] Hart lamented, “I could never believe that British Americans would be guilty of such a crime, I mean that of the horrible slave trade, carried on by numbers and tolerated by the authority in this country.”[13]

In Massachusetts, more religious men spoke out. Deacon Benjamin Colman of Newbury, in two pieces published in a Newburyport newspaper in 1774, called slavery “a God-provoking and wrath-procuring sin,” and the next year identified the slave trade a “crime . . . more particularly pointed . . . than any other.”[14] In 1775, preacher Nathaniel Niles of Newburyport, exclaimed in a sermon, “God gave us liberty, and we have enslaved our fellow-men. May we not fear that the law of retaliation is about to be executed on us?”[15]

The Rev. Samuel Hopkins expressed disappointment that more of his fellow Congregational clergymen in New England did not speak out opposing the slave trade. He once wrote, “The Friends [Quakers] have set a laudable example in bearing testimony against the slave trade . . . and I must say have acted more like Christians in this important article than any other denomination of Christians among us. To our shame be it spoken!”[16] One of the problems for the Congregationalists was that unlike the Quakers with their monthly, quarterly, and annual meetings, there was no umbrella organization over the Congregationalist churches that could help to formulate a unified position. Still, the opinions expressed by Hopkins, Allen, Edwards and a few others was a start, and they would influence New England town meetings in the 1770s prior to the outbreak of the Revolutionary War.

The 1760s and 1770s were times of great political fervor in the thirteen colonies. By 1774, the political lives of many Americans had been radicalized by the Whig cause. Writing years after the Revolutionary War ended, John Adams penned to Thomas Jefferson:

What do we mean by the Revolution? The War? That was no part of the Revolution. It was only an effect and consequence of it. The Revolution was in the minds of the people, and this was effected from 1760 to 1775, in the course of fifteen years before a drop of blood was drawn at Lexington.[17]

The increasing politicization and radicalism of Whigs showed itself in other arenas too, including with antislavery efforts. Whigs (also known as Patriots) who favored liberty for all and who opposed slavery realized that before that institution could be ended, importations of enslaved persons first had to cease. They realized it would be too radical for many of their fellow citizens—and for their British rulers—to press for an immediate end to slavery, when the institution had existed for more than a century in their colonies. But they also recognized that the terrible institution could be weakened by halting the importation of enslaved persons into their colonies. The main source of importations was, of course, the African slave trade.

On its face, prohibiting slave imports was not a big step in the North. One report (likely not complete) indicates that from 1769 to 1772, there were no imports of captive Africans by any Northern colony, with the exception of New York, which imported sixty-seven in 1770 and nineteen in 1772.[18] Still, as will be seen below in the language used by many Patriots, limiting slave imports was seen as a principled first step in eventually prohibiting slavery itself in the colony. Antislavery advocates even in the North were not yet willing to promote seriously the end of slavery, when so many of their residents still owned slaves.[19]

The effort to limit the importation of enslaved persons started, not surprisingly, in Massachusetts. Massachusetts had been the colony where the slave trade had first taken root in North America in the seventeenth century, but by the 1760s only a few of its merchants were active in the trade. (Prior to direct American involvement, Dutch and English traders supplied slaves to the American colonies, and British slave traders continued to do so throughout the period.) There was an uptick, however, in slave trading by Boston merchants in the 1770s. From 1771 to 1774, Boston and other Massachusetts merchants on the average sent at least six vessels to the African coast, debarking their captives in the Caribbean or the South.[20] Moreover, while Massachusetts’s economy was not slave based as it was in Southern colonies, about one and a half percent of its population still consisted of enslaved persons at this time.

At the time, efforts were not made to prohibit all participation of Massachusetts residents in the slave trade. This was probably because the colonists believed they did not have the authority to take such a step and that only London officials could prohibit the trade. In this, the colonists were correct. Therefore, the importation of enslaved persons became the focus of local antislavery efforts.

James Otis of Massachusetts, in his influential 1763 pamphlet, The Rights of the British Colonies, on the rights of colonists not to be taxed without their consent, asserted that there were laws higher than acts of Parliament. Otis identified natural rights held by all men as divinely inspired. While not necessary to do so to make his main point, he delved into race relations. He exclaimed: “The colonists are by the law of nature free born, as indeed are all men, white or black . . . Does it follow that ‘tis right to enslave a man because he is black?” Speaking of the African slave trade, he said, “Nothing better can be said in favor of a trade that is the most shocking violation of the law of nature, has a direct tendency to diminish the idea of the inestimable value of liberty, and makes every dealer in it a tyrant, from the director of an African company to the petty chapman in needles and pins on the unhappy coast. It is clear truth that those who every day barter away other men’s liberty will soon care little for their own.”[21]

Otis’s sentiments were impressive for the time. Perhaps using his influence as a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, that legislative body for the first time considered a bill to prohibit the importation of slaves into the colony, but it was not acted upon.[22]

Samuel Dexter, a local Boston politician, recalled after the Revolutionary War, “about the time of the Stamp Act, what before were only slight scruples in the minds of conscientious persons became serious doubts, and, with a considerable number, ripened into a firm persuasion that the slave trade was malum in se” [Latin, “wrong in itself”].[23] Items began appearing in Massachusetts newspapers and pamphlets opposing the slave trade in 1766.[24] In that year, the town meeting of Worcester instructed its representative to the Massachusetts legislature to use his influence “to obtain a law to put an end to the unchristian and impolitic practice of making slaves of the human species in this province.”[25] James Swan in 1772 wrote an influential pamphlet, arguing that slavery was contrary to scripture and that the slave trade depopulated Africa, kept it in a constant state of conflict in the effort to acquire captives to sell for slaves, and hindered the development of a profitable trade in precious metals, ivory, and spices. Republished the next year, its appeal to abolish the slave trade in the province was addressed to the Massachusetts Governor, Council, and the House of Representatives. It was reprinted “at the earnest desire of the Negroes in Boston,” in order that a copy might be sent to each Massachusetts town with a view to instructing their legislators.[26] At the Harvard College commencement in 1773, two Newbury graduates debated the morality of “enslaving Africans.”[27]

The first serious efforts to end slave importations began ten years before the Declaration of Independence. On May 6, 1766, the Boston town meeting re-elected James Otis, Samuel Adams, and Thomas Cushing to the General Assembly (Massachusetts’s legislature), and voted in John Hancock for the first time. That month the Boston town meeting instructed them to push for “a law, to prohibit the importation and purchasing of slaves” in Massachusetts. The town meeting was hopeful it would lead to the “the total abolishing of slavery from among us.”[28] In June, the House of Representatives appointed a committee that included Otis, Adams, and Hancock, to “prepare and bring in a bill at the next session to prohibit the importation of slaves for the future.”[29]

The next year, in March, the Boston town meeting again expressed its support of such a bill.[30] The Whig firebrand from Boston and one of the leaders of the resistance to British authority, Samuel Adams, then introduced a bill in the Massachusetts House of Representatives that went even further than prohibiting the importation of slaves. It was entitled, “A Bill to prevent the unwarrantable and unusual practice or custom of enslaving Mankind in this Province, and the importation of slaves into the same.”[31] The House, not ready for an outright ban, as an alternative, appointed a committee to provide for taxing the importation of slaves as a measure to discourage slave importations into the colony.[32] But the bill died in the more conservative upper chamber, the Council. According to Samuel Dexter, who strongly supported the bill, “Had it passed both houses,” the royal governor, Francis Bernard, “would not have signed it. The duty was laid high.”[33]

In 1771 antislavery representatives tried again. A representative from the town of Hadley, on April 9, 1771, introduced a bill to “prevent the importation of slaves from Africa.”[34] This time the legislation passed the House of Representatives and the Council, but the royal governor, Thomas Hutchinson, vetoed it.[35] In early 1773, another effort was made to pass a nonimportation of slaves bill; this time it passed the Council, but the House carried it over to 1774.[36]

The Massachusetts government also began seeing new petitions from the enslaved persons themselves. A self-styled “humble petition of many slaves” submitted in January 1773 was the first public protest against slavery made by Blacks to a New England legislature.[37] Later in June 1773, four Boston enslaved persons submitted a petition to Governor Hutchinson and the Massachusetts legislature proposing the end of slavery in the colony and making direct analogies to white Patriots seeking to avoid “slavery” imposed on them by far-away powers in Britain.[38] The Black men submitting this petition approached Samuel Adams for his assistance, which speaks well of Adams’s reputation in the Black community.[39] More enslaved persons submitted another petition in 1774, which, like the others, went unaddressed.[40] Massachusetts lawmakers were prepared to address the importation of slaves, but not yet their freedom. Still, the issue had been raised and made public.

In 1773, in May, when town meetings were typically held, Massachusetts Patriots throughout the colony, engulfed in the rhetoric of liberty and natural rights of all men, again turned their attention to slavery. The Salem town meeting instructed its representatives to endeavor to prevent slave importations as “repugnant to the natural rights of mankind, and highly prejudicial to this Province.”[41] The town meeting of Leicester instructed its representative to the House of Representatives as follows:

And, as we have the highest regard for (so as to even revere the name of) liberty, we cannot behold but with the greatest abhorrence any of our fellow-creatures in a state of slavery. Therefore, we strictly enjoin you to use your utmost influence that a stop may be put to the slave trade by the inhabitants of this Province, which, we apprehend, may be effected by one of two ways: either by laying a heavy duty on every negro imported or brought from Africa or elsewhere into this Province, or by making a law that every negro brought or imported as aforesaid should be a free man or woman as soon as they come within the jurisdiction of it . . . Thus, by enacting such a law, in process of time will blacks become free.[42]

The town meetings of Sandwich and Medford, and probably more, issued similar instructions to their respective representatives in May 1773. Medford went even further, directing its representative also to “use his utmost influence to have a final period put to that most cruel, inhuman and unchristian practice, the slave trade.”[43]

Finally, in early March 1774, both houses passed a bill to prohibit slave imports. Governor Hutchinson lumped this bill with others as inconsistent with the “authority of the King and Parliament” and refused to sign it. The Massachusetts legislature enacted the same prohibition again, but the new governor, Gen. Thomas Gage, refused to sign the measure on the ground that he had no authority to do so absent instructions from London, a position that was legally correct.[44] The British government had no interest in threats to limiting or ending its lucrative slave trade. Rhode Island and Connecticut lacked a royal governor and, thus, they were relatively unfettered by oversight from London.

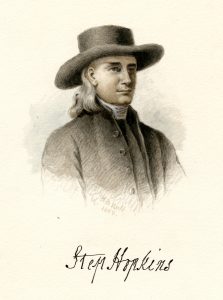

Rhode Island’s dominant politician in the years leading up to the American Revolution, and the leader of its most popular faction, was Stephen Hopkins, who served as governor numerous times and would sign the Declaration of Independence. One of the oldest of the Founders, he was a long-time friend of Benjamin Franklin. With his Quaker upbringing, he typically donned a plain grey suit and simple broad-rimmed felt hat. Even though he received no formal schooling, he became widely read, and in 1765 he showed off his learning in a respected pamphlet opposing the Sugar Act and trade regulations. Hopkins was a slaveowner who, after pressure from the Quakers, freed his enslaved persons in 1772 and 1773, except for one enslaved woman. For this he was expelled from the Society of Friends in 1773. Hopkins’s public views on slavery did evolve. By the eve of the American Revolution, Hopkins, the Quaker Moses Brown, and the Rev. Samuel Hopkins (no relation) became a powerful triumvirate in Rhode Island opposing both slavery and the slave trade.

On May 17, 1774, the town meeting of Providence, Rhode Island, instructed its representatives to the General Assembly to obtain an act banning the importation of slaves, and to free all slaves born in the colony after they reached maturity.[45] With Stephen Hopkins and Moses Brown working behind the scenes, Rhode Island complied with the first request, banishing the importation of enslaved persons in June of that same year.[46]

It is noteworthy to consider the high-sounding preamble to the law Rhode Island passed in 1774 prohibiting the importation of enslaved persons, given Rhode Island’s prominence in the slave trade, having sent out the most ships to Africa each year (about twenty-two annually) of any colony. Probably penned by Stephen Hopkins, the recital justified the ban on the ground that “the inhabitants of America are generally engaged in the preservation of their own rights and liberties, among which, that of personal freedom must be considered as the greatest; as those who are desirous of enjoying all the advantages of liberty themselves should be willing to extend personal liberty to others.”[47] Note that the recital addressed the evils and inconsistencies of slavery as a whole, and not just the slave trade. The radical Patriots, including those opposing slavery, were in ascendancy. Newport slave merchants were not influential leaders in the Patriot cause.

Still, with a higher percentage of slaves than any other New England colony, and the one most implicated in the slave trade, Rhode Island legislators were not yet willing to press for an end to slavery in the colony or its participation in the slave trade. In a concession to slave traders, in the nonimportation bill, the legislators allowed them to bring enslaved persons into the colony for no longer than a year if those persons were on board their ships, had been obtained in Africa, and had not been sold in the Caribbean—and only after posting a bond of £100 for each such captive.[48]

To the chagrin of the Rev. Samuel Hopkins and Moses Brown, the Rhode Island ban applied only to the importation of slaves. It did not prohibit Newport merchants sending voyages to the west coast of Africa and bringing captives to the Caribbean for sale there. Still, the ban on importations of enslaved persons by the colony most deeply engaged in the trade represented progress for the growing antislavery movement. Even the great slave-trade historian Elizabeth Donnan, whose work covered the African slave trade from the fifteenth century in vivid detail, called Rhode Island’s slave importation ban “a substantial gain. Dr. Hopkins need not have felt so much discouragement.”[49]

In Connecticut, the Rev. Levi Hart urged its residents to follow Rhode Island’s example on grounds of morality, religion and public spirit. A few weeks later, Connecticut’s Assembly also ended slave importations.[50]

[1]David Eltis and David Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 13. The leading online source of information on African slave trading voyages concludes that British ships carried twenty-six percent of all African captives. Voyages, The Trans-Atlantic Salve Trade Database, www.slavevoyages.org/assessment/estimates (using search terms “Flag” and “Only Embarked”).

[2]Eltis and Richardson, Atlas, 25-27.

[3]Ibid., 23, 26-27. The leading online source of information on African slave trading voyages concludes that North American ships carried 2.4 percent of all African captives. Voyages, The Trans-Atlantic Salve Trade Database, at www.slavevoyages.org/assessment/estimates (using search terms “Flag” and “Only Embarked”); see also Stephen D. Behrendt, “The Transatlantic Slave Trade,” in Robert L. Paquette and Mark M. Smith, eds., Slavery in the Americans (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2010), Table 11.1, 263 (same, 2.4 percent).

[4]For more on Rhode Island’s dominance in the North American slave trade (particularly Newport), see Jay Coughtry, The Notorious Triangle: Rhode Island and the African Slave Trade, 1700-1807 (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1981).

[5]Eltis and Richardson, Atlas, 17-19. Trans-Atlantic Salve Trade Database concludes that 3.6 percent of all African captives disembarked in the New World were carried to North America. Voyages, The Trans-Atlantic Salve Trade Database, www.slavevoyages.org/assessment/estimates (using search terms “Broad disembarkation regions” and “Only Disembarked”); see also Behrendt, “The Transatlantic Slave Trade,” Table 11.1, 263 (3.7 percent).

[6]David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, 1770-1823 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1975), 48.

[7]W. E. B. DuBois, The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America, 1638-1870 (New York, NY: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1896), 41.

[8]Dwight L. Dumond, Antislavery: The Crusade for Freedom in America (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1961), 19; see also Arthur Zilversmith, The First Emancipation, The Abolition of Slavery in the North (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1967), 79-81 and 89-93.

[9]Joanne Pope Melish, Disowning Slavery, Gradual Emancipation and “Race” in New England, 1780-1860 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998), 50.

[10]Samuel Hopkins, A Dialogue Concerning the Slavery of the Africans . . . (Norwich, CT: Judah P. Spooner, 1776), 6 and 17.

[11]Quoted in Stewart M. Robinson, Political Thought of the Colonial Clergy, Words of the Declaration of Independence Foreseen in the Writings of Clergymen Prior to July 1776 (Privately Printed, 1956),36.

[12]Quoted in Joseph Conforti, Samuel Hopkins & the New Divinity Movement (Grand Rapids, MI: Christian University Press, 1981), 127.

[13]Quoted in Robinson, Political Thought of the Colonial Clergy, 33.

[14]Quoted in Joshua Coffin, A Sketch of the History of Newbury, Newburyport, and West Newbury (Boston, MA: Samuel G. Drake, 1845), 339-40 (citingEssex Journal).

[15]Quoted in Robinson, Political Thought of the Colonial Clergy, 33.

[16]S. Hopkins to M. Brown, April 29. 1784, in Edwards A. Park, Memoir of the Life and Character of Samuel Hopkins, D.D.,2nd ed. (Boston, MA: Doctrinal Tract and Book Society, 1854), 120.

[17]J. Adams to T. Jefferson, August 24, 1815, in J. Jefferson Looney, ed., Jefferson Papers, Retirement Series, vol. 8 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011), 682-83.

[18]Slave Trade by Origin and Destination, 1768 to 1772, in Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970, Part 2 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, 1975), 1172.

[19]See Melish, Disowning Slavery, 52-53 and n8.

[20]Custom House Items, 1771-1774, in Elizabeth Donnan, ed., Documents Illustrative of the History of the Slave Trade to America, vol. 3 (Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution, 1932),3: 76.

[21]James Otis, “The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved,” in Gordon Wood, ed., The American Revolution. Writings from the Pamphlet Debate. 1764-1776, 2 vols. (New York, NY: Library of America, 2015), 1: 69-70.

[22]Minutes, January 6 and February 2, 1764, in Journals of the House of Representatives of Massachusetts, vols. 37-47 (1760-1771), (Reprint, Boston, 1965-78), 40: 170 and 263.

[23]S. Dexter to Dr. Belknap, February 23, 1795, in “Queries Relating to Slavery in Massachusetts,” Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Series 5, vol. 3 (1887), 385.

[24]See Donnan, Documents of the Slave Trade 3: 73n2.

[25]Worcester Town Meeting instructions, May 19, 1766, in William Lincoln, History of Worcester, Massachusetts . . . (Worcester, MA: Charles Hersey, 1862), 68.

[26]James Swan, A Dissuasion to Great Britain and the Colonies, from the Slave-Trade to Africa. Showing the Injustice Thereof (Boston, 1773) (originally published in 1772), ix-x, 18, 43; see also Zilversmith, First Emancipation, 99-100.

[27]See Coffin, History of Newburyport, 339; Donnan, Documents of the Slave Trade 3: 73n2.

[28]Boston Town Meeting vote for representatives, May 6, 1766, in, A Report of the Record Commissioners of the City of Boston Containing the Boston Town Records,1758-1769 (Boston, MA, 1886)16: 183; Town Meeting instructions to representatives, May 27, 1766, in ibid., 183.

[29]Minutes, June 10, 1766, in Journals of the House of Representatives of Massachusetts, 40: 110.

[30]Boston Town Meeting resolution, March 16, 1767, in, Boston Town Records, 16: 200.

[31]Minutes, March 13, 1767, in Journals of the House of Representatives of Massachusetts 43: 387; see also Douglas R. Egerton, Death or Liberty, African Americans and Revolutionary America (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2009),56.

[32]Minutes, March 14 and 16, 1767, in Journals of the House of Representatives of Massachusetts 43: 390, 393.

[33]Dexter to Dr. Belknap, February 23, 1795, in “Queries Relating to Slavery in Massachusetts,” Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Series 5, vol. 3 (1887), 384; see also George H. Moore, Notes on the History of Slavery in Massachusetts (New York, NY: D. Appleton, 1866), 126-28.

[34]Minutes, April 19, 1771, in Journals of the House of Representatives of Massachusetts, 47: 197.

[35]Moore, Notes on the History of Slavery in Massachusetts, 130-32.

[36]Minutes, January 28, February 2 and March 5, 1773, in Journals of the House of Representatives of Massachusetts, 49: 195, 204-05, 287.

[37]Minutes, Jan. 28, 1773, in ibid., 49: 195.

[38]Melish, Disowning Slavery, 80-81.

[39]See S. Adams to J. Pickering, January 8, 1774, in Harry Alonzo, ed., The Writings of Samuel Adams, vol. 2 (New York, NY: Putnam, 1907), 78; Ira Stoll, Samuel Adams. A Life (New York: Free Press, 2008), 116-17.

[40]See Benjamin Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Co., 1961), 39-40.

[41]Salem Town Meeting Resolution, May 18, 1773, in James B. Felt, Annals of Salem, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (Salem, MA: W. & S. B. Ives, 1849); 2:416-7.

[42]Leicester Town Meeting Instruction, May 19, 1773, quoted in Emory Washburn, Historical Sketches of the Town of Leicester, Massachusetts (Boston, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1860), 442-43.

[43]Sandwich Town Meeting Resolution, May 18, 1773, in Frederick Freeman, The History of Cape Cod. The Annals of The Thirteen Towns of Barnstable County, vol. 2 (Boston, MA: Privately Printed, 1862), 2:114-15; Medford Town Meeting Resolution, 1773, quoted in Moore, Notes on the History of Slavery in Massachusetts, 133.

[44]Minutes, March 2-7, 1774, and June 16, 1774, in Journals of the House of Representatives of Massachusetts 50:221, 224, 226, 228, and 237; Message from Governor T. Hutchinson to the Council and House, March 8, 1774, in ibid., 243; Minutes, June 16, 1774, in ibid., 287; S. Dexter to Dr. Belknap, Feb. 26, 1795 and March 19, 1795,, in “Queries Relating to Slavery in Massachusetts,” Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Series 5, vol. 3 (1887), 388 and 395 and note; see also Moore, Notes on the History of Slavery in Massachusetts, 142-43; Egerton, Death or Liberty, 56; DuBois, Suppression of the Slave Trade, 32.

[45]Quoted in William R. Staples, Annals of Providence (Providence, RI: Privately Printed, 1843), 235-36.

[46]Resolution, June 1774 session, in John R. Bartlett, ed., Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, vol. 7 (Providence, RI: A. C. Greene, 1862), 251-52; Mack Thompson, Moses Brown, Reluctant Reformer (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press,1962),97.

[47]Resolution, June 1774 session, in Bartlett, Records of Rhode Island 7:251.

[49]Donnan, Documents of the Slave Trade 3:335, n.1.

[50]Resolution, Oct. 1774 session, in Charles J. Hoadley, ed., The Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut 15 vols. (Hartford, CT: Case, Lockwood & Brainard, 1887), 14:329.

6 Comments

Another Massachusetts minister spoke publicly against the slave trade on 30 May 1770 when the new legislature convened on the campus of Harvard College. The Rev. Samuel Cooke, minister in the village of Menotomy (now Arlington), preached to the legislators and acting governor. While avoiding some of the most controversial issues of the day, Cooke said: “I trust, on this occasion, I may, without offence—plead the cause of our African slaves; and humbly propose the pursuit of some effectual measures, at least, to prevent the future importation of them.” As the article says, the Massachusetts legislature did not act on this call in this term, and when it did pass measures against importing enslaved people the royal government vetoed them.

Thanks John! I would appreciate your emailing me the citation. Best, Christian

Excellent pieces on the little-known anti-slavery sentiment in the colonies.

Fantastic piece.

Thanks Paul!

Great work, keep it up!