In the years leading up to the Revolutionary War, as the British Army repositioned its forces from western frontier posts into American cities, many Americans seethed against quartering troops in urban centers. Animosity with the military occupation was rampant but was not the universal reaction in every location. In two cities, colonial anger ranged from vituperative verbal abuse to outbreaks of destructive violence. On January 19, 1770, New York residents briefly held captive several British soldiers who posted broadsides obnoxious to the radical Sons of Liberty. When additional soldiers arrived, a melee ensued with several injuries on both sides. The ruckus became known as the Battle of Golden Hill.[1] Just a few weeks later, a more serious incident occurred in Boston. On March 5, 1770, soldiers from the British garrison in Boston opened fire on a taunting group of agitators, killing three and wounding eight others (two of whom eventually died). Protesting propagandists cleverly coined the incident as the “Boston Massacre.” Generally, historians depict these two violent events as representative of all colonial reactions to the quartering of British troops in American cities. Just a few weeks later, however, this was not the case in a New Jersey town located only thirty-five miles from New York City.

British military commanders posted a portion of the 26th Regiment of Foot in the commercially important trading town of Brunswick (present-day New Brunswick), New Jersey. Located on a navigable portion of the Raritan River, Brunswick consisted of one hundred and fifty houses and three churches. During the French and Indian War, the colony of New Jersey constructed barracks on George Street near the intersection of Barracks (later renamed Patterson) Street for the use of the British Army. Purposely sited on the road out of town, the two-story stone building was designed to billet three hundred enlisted soldiers. In 1770, men from several companies of the 26th Regiment and their families had occupied the barracks for almost three years. On a voluntary basis, officers paid local residents to board in their homes. During this period, the officers and enlisted soldiers developed an excellent working relationship with the community.

A career officer, Maj. Charles Preston (not related to Capt. Thomas Preston of the 29th Regiment who was involved in the Boston Massacre), commanded the troops in Brunswick. Scottish by heritage, a contemporary described Preston’s character as “worthy, decent, fine tempered.”[2] The residents of Brunswick heartedly concurred. On May 14, 1770, upon learning of the redeployment of the 26th Regiment to New York City, the Brunswickers wrote a public letter to Preston which opened, “Prompted by a pleasing Reflection on the Tranquility we have enjoyed from the Harmony that has uniformly subsisted between the Inhabitants, and the Troops quartered in the Barracks here under your immediate Command, for now near three Years, we wait upon you in Order to express our unfeigned Satisfaction.” The inhabitants’ letter goes on to express “cordial thanks” for the “laudable Disposition” and remarkably concludes with thanks for “Peace and good Order, without the least Infringement on our Rights and Privileges.” The letter ends with a wish for “your Honour and Happiness in future life.”

To celebrate and give thanks, the townspeople invited Major Preston and the other officers to a gala dinner at the locally prominent Whitehall Tavern, the largest venue in town. Remarkably, residents felt free to publish without retribution from the Sons of Liberty a public notice of the letter and the dinner in a New York newspaper, albeit a Loyalist-leaning newspaper. The reporters noted that the town’s citizens provided “a genteel Entertainment.”[3] Occurring just a few weeks after the Battle of Golden Hill and the Boston Massacre, the Brunswick celebratory address and festive event stood in stark contrast to the extremely troubled relations between British troops and American colonists nearby New York City and in Boston.

What was so different about the state of affairs in New Brunswick than other locations which quartered British troops? Similar to Boston, New York City and many colonial cities, Brunswick citizens actively participated in militant organizations including the Sons of Liberty and Committees of Correspondence. Brunswick chapters of these groups were less radical but were nonetheless firm in their convictions that British taxes and ministerial retaliations against Boston should be resisted. Rather than differences in rebellious ardor, the positive Brunswick-British Army relationships emanated from other factors. First, British military planners presciently deployed the 26th Regiment in Brunswick, Perth Amboy, and Elizabethtown (present-day Elizabeth) which avoided exceeding the barracks capacities and housing accommodations in any one location. Secondly, spending and participating in the local economy by the British soldiers provided a demonstrably positive financial impact for the local citizenry. Given the surrounding agricultural opportunities and commercial trading businesses, less competition existed for employment between local residents and moonlighting British soldiers. Contrary to the situations in Boston and New York City, farmers and traders welcomed access to temporary labor especially during periods of peak demand. Further, the 26th Regiment recruited quite a few Americans which added to the goodwill with the local residents.[4]

The most important reasons for the considerable harmony lay in family and personal areas. During the 26th Regiment’s almost three year stay in Brunswick, “upwards of fifty Children have been born in the Barracks.” This is a prodigious number of new fathers among the one hundred and sixty soldiers stationed in the town. It is likely that approximately twenty-five percent of the soldiers were married, resulting in one or two births per married soldier.[5] Further demonstrating the happiness of the regiment, “only two Men out of the one Hundred and Sixty of which they consisted have died, one a natural Death, and the other by Accident,” a remarkably low death rate for British troops deployed on overseas assignments.[6] The high number of children born and the low death rate were indicators of less drunk and disorderly behaviors by soldiers, a problem which plagued residents of other towns housing British troops.[7]

Reactions to the laudatory Brunswick address from the two other towns quartering soldiers of the 26th Regiment ranged from supportive to neutral. When Elizabethtown residents read the Brunswick address in the Loyalist leaning New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, the Elizabeth town clerk asked the editor to print their own approbatory but not previously published address to the departing troops. Not to be outdone, the Elizabethtown leaders pointed out that their address to the 26th Regiment officers preceded the Brunswickers’ version.[8] No public reaction emanated from the Perth Amboy town leaders and citizens. Given that the Royal Government under the direction of Gov. William Franklin was located in Perth Amboy, one would have thought that its leadership would have also jumped on the bandwagon and sent its own letter praising the performance of the 26th Regiment.

Acknowledging the praise and appreciation from Brunswick’s leaders, Major Preston responded in writing to the town’s inhabitants a few days after the sendoff dinner. He thanked the residents “for the Honour you have done me, by your kind and obliging Address and receive with the greatest Pleasure this public testimony of your Approbation of my conduct, and the Behavior of the troops under my command.” He went on to cite the “good Disposition of the Inhabitants” which “will always claim my Gratitude and best Wishes for their Prosperity.”[9]

Five short years later, Major Preston had an opportunity to reconsider his protestations of eternal gratitude. In command of elements of the 26th Regiment and other assorted units, the major signed articles of capitulation to an invading American army in St. Johns, Canada. Stridently, his key demand during the surrender negotiations was to remove any hint of British impropriety with respect to its North American colonies.[10] Despite successfully holding off a besieging force for fifty-three-days and capitulating only because of a lack of ammunition and supplies to continue resistance, the surrender inappropriately tainted Preston’s military career. Shortly after a prisoner exchange, Preston returned to Scotland a civilian, inherited a barony, and became a loyal Tory member of Parliament.[11]

As for the Brunswickers, relations with the British Army first cooled and then inexorably shattered. The 29th Regiment, whose soldiers participated in the Boston Massacre, replaced Preston’s command in Brunswick. What went through the minds of the town’s residents when the 29th Regiment arrived is not recorded, but needless to say, the town held no further dinners feting the British troops. Similar to other colonies, the town’s praise of the local soldiers did not translate into paying its share to financially support the British forces as required under the Quartering and Mutiny Acts.[12] Contrary to local economic interests, but supportive of their neighboring colonies, the Brunswickers joined the colonial boycott of British goods. When war erupted, any goodwill towards the soldiers now viewed as occupiers evaporated in the ensuing violence.

Strategically located between New York and Philadelphia, Brunswick and its citizens quickly became embroiled in revolutionary politics and military campaigns. While from time to time George Washington and other Rebel leaders complained about their poor turnout among New Jersey militia, leading Brunswick merchants and influential citizens joined and commanded an active militia.[13] In early 1776, the first session of the newly constituted New Jersey legislature met to plan the state’s contributions to war effort in Whitehall tavern, the site of the earlier dinner honoring the 26th Regiment. A year and a half later, the 26th Regiment marched back into town past the Whitehall Tavern, not as peaceful protectors, but as attacking occupiers.[14] To defend against a surprise attack similar to the 1776 assault on the unfortified Trenton, the 26th Regiment constructed redoubts and other fortifications around the city.[15] British commander Gen. William Howe sought to entice the Continental Army out of the Watchung Mountains onto the open Jersey plains for a decisive battle. Brunswick served as a key supply and communications center to support this campaign. General Washington did not take the bait, but did harass Howe’s forces on their retreat to Staten Island and New York City including skirmishing in and around Brunswick. Further demonstrating that war had changed everything, British forces burned numerous homes and other buildings, devastating the area. Throughout the conflict, British army units were not safe from attack by militia in and around Brunswick.[16]

The account of local residents giving thanks to a departing military commander contrary to national political concerns is a good reminder that all politics is local and that in some cases, personal relationships can transcend broader differences. Brunswick residents were not taking sides in the larger geopolitical dispute when sending the public letter to Major Preston. Simply, they were giving sincere thanks for keeping his soldiers in order and under control. In a small town, with no other means of protection from often-unruly troops, peace and safety were paramount issues. This episode demonstrates that there was not a straight line between high-profile events such as the Battle for Golden Hill and the Boston Massacre to the War for Independence. As evidenced in Brunswick, there were countervailing episodes, just not enough to turn the colonists’ attitudes back towards allegiance to the British Crown.

[1]For a complete account of the events leading up to the Battle of Golden Hill and its location on contemporary Manhattan Island, see allthingsliberty.com/2020/02/the-grand-affray-at-golden-hill-new-york-city-january-19-1770/.

[2]James Boswell, The Yale Editions of the Private Papers of James Boswell: Correspondence (United Kingdom: McGraw-Hill, n.d.), 8: 168.

[3]“The Address of sundry of the Magistrates, Freeholders, and Inhabitants of the city of New-Brunswick, in the Province of New Jersey,” New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, Monday May 21, 1770.

[4]S.M. Baule, Protecting the Empire’s Frontier: Officers of the 18th (Royal Irish) Regiment of Foot during Its North American Service, 1767–1776 (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2014), 18.

[5]The estimate of the number of wives posted with the 26th Regiment is derived from prisoner of war records in 1775 which listed women captured with the regiment in Canada. Kenneth Baumgardt, “The Royal Army in America During the Revolutionary War The American Prisoner Records” (Christiana, Delaware: Department of Defense, US Army Corps of Engineers, 2008), www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a491107.pdf.

[6]“Maj. Preston’s Answer,” New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, Monday, May 21, 1770.

[7]For a scholarly assessment of alcohol abuse in the British Army see, Paul E. Kopperman, “The Cheapest Pay: Alcohol Abuse in the Eighteenth-Century British Army,” The Journal of Military History, Vol. 60, No. 3 (Jul., 1996): 445-470, www.jstor.org/stable/2944520.

[8]“Letter to the Editor,” New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, Monday May 28, 1770.

[9]“Maj. Preston’s Answer,” Ibid.

[10]Michael P. Gabriel, Major General Richard Montgomery: The Making of an American Hero (Madison, NJ and London: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press ; Associated University Press, 2002), 128.

[11]“Preston, Sir Charles, 5th Bt. (c.1735-1800), of Valleyfield, Firth,” The History of Parliament. www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1754-1790/member/preston-sir-charles-1735-1800.

[12]Thomas Gage to Earl of Hillsborough, November 6, 1771, K. G. Davies, Documents of the American Revolution 1770-1783 (Colonial Office Series)(Shannon, Ireland: Irish University Press, 1973), 3: 231.

[13]One of many examples of George Washington’s negative views on the New Jersey militia. In this case, he blamed their lack of mustering on his 1776 defeats in New Jersey: George Washington to Lund Washington, December 10-17, 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-07-02-0228;.original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 7, 21 October 1776–5 January 1777, ed. Philander D. Chase (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1997), 289–292.

[14]Archibald Robertson, Archibald Robertson: His Diaries And Sketches In America, 1762-1780 (New York: New York Public Library, 1971), Book 2, 136.

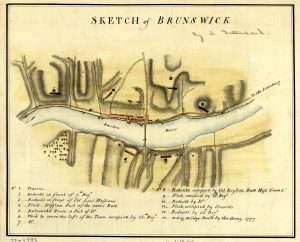

[15]For a map of the city and the British fortifications, see Alexander Sutherland and John Hills, Sketch of Brunswick. Sketch of the ground near Mr. Low’s at Rariton Landing, 1777, Map, www.loc.gov/item/gm72003593/.

[16]The highest ranking Brunswicker in the Continental Army was Brig. Gen. Anthony Walton White. A leading merchant, Col. John Neilson led the Middlesex County/Brunswick militia. For an example of the local militia attempts to attack the British forces around Brunswick see allthingsliberty.com/2017/07/battle-bennetts-island-new-jersey-site-rediscovered/.

One thought on “Countervailing Colonial Perspectives on Quartering the British Army”

This is a really valuable article, not just for the perspective on quartering, but because it illustrates the complicated relationship between colonials and British authority in the years leading up to the war. Kudos!