Every nation has an origin story. In the popular imagination, the American Revolutionary War has been a tale of heroes who were forged in adversity, overcame an arch-enemy, and carried their new-found virtue and power into the world. In other words, the Revolutionary War is a perfect match for superheroes. In the early days of the comic books, some superheroes drew their power from the War of Independence, giving inspiration to Americans who were living through another dire conflict.

The superhero comic book was born of war. The genre took off—quite literally—with the introduction of Superman in Action Comics#1, which hit the newsstands on April 18, 1938 and became an immediate hit.[1] By that month, Nazi Germany had annexed Austria, and the forces of Imperial Japan had pushed far into China. As the world descended into darkness, comic book creators hearkened back to America’s past for inspiration. The times called for patriotism, and the magic of the comics could deliver it.

Surprisingly, the first superhero creation that was inspired by the Revolution wasn’t clad in red, white, and blue. Instead, he was the famously dark Batman. Writer Bill Finger recalled how he co-created the character in 1939:

Bruce Wayne’s first name came from Robert [the] Bruce, the Scottish patriot. Wayne, being a playboy, was a man of gentry. I searched for a name that would suggest colonialism. I tried Adams, Hancock . . . then I thought of Mad Anthony Wayne.[2]

Years later, other writers memorialized this lore by establishing that Bruce Wayne is descended from Gen. Anthony Wayne, the great commander of the Pennsylvania Line, and that Wayne Manor and the Batcave sit on property given to the general for his service during the Revolutionary War.[3]

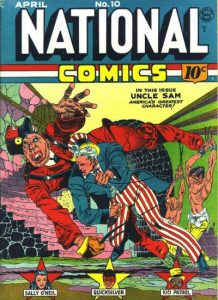

As the Battle of Britain got underway in July 1940, a quintessentially American superhero appeared in National Comics#1. Uncle Sam was a slain Revolutionary War soldier who returned whenever his country needed him.[4] As the personified spirit of America, Uncle Sam possessed incredible strength. He could also grow to great heights, tall enough to stride across the ocean. It was a striking metaphor, given that America hadn’t yet sent troops to the aid of Great Britain.

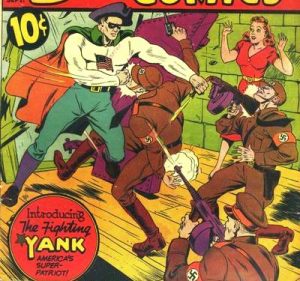

By 1941, Americans were buying fifteen million comic books every month,[5] and titles such as Captain Americawere outselling magazines like Time.[6] Patriotic superheroes exploded across their pages. Among them was the Fighting Yank, who obtained a magic cloak of invulnerability from the ghost of his Revolutionary War ancestor (and accessorized it with a tricorn hat). He was followed shortly by The Flag, who had a vision of George Washington and received the gifts of super-speed and strength.[7] And there was the Unknown Soldier, who claimed to be powered by those who had died protecting the United States; he defeated Adolf Hitler in his very first outing in the summer of 1941.[8]

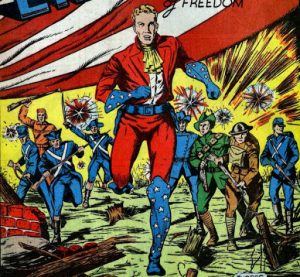

Perhaps no superhero was in touch with the past better than history professor John Liberty. Enraged by sabotage at a nearby government arsenal, Liberty wished that the spirts of old could help keep freedom alive. His wish was granted, and the professor gained the power to summon American patriots. (He also gained an eighteenth-century neck ruffle and star-spangled boots.) In his first adventure he captured Fifth Columnists with the help of Paul Revere, Ethan Allen, and the Green Mountain Boys.[9]

The comics even supplied something that both the Revolution and World War II were short of: female combatants. After escaping from Nazi-occupied Europe, reporter Libby Lawrence learned to draw superhuman stamina, speed, and strength from the Liberty Bell at Independence Hall.[10] Naturally taking the name Liberty Belle, she battled through World War II, culminating with a mission in the Philippines.[11]

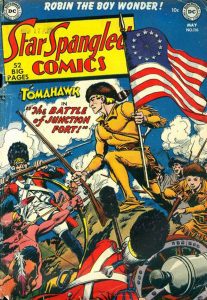

During this Golden Age of comics, few heroes had their stories set during the Revolution itself. (Perhaps because the Colonies lacked the chemical laboratories and sci-fi inventions that tend to spawn superpowers.) The exception was Tomahawk, who first appeared in Star Spangled Comics#69 in 1947. A buckskin-clad frontiersman, Tom Hawk became one of George Washington’s most capable operatives, and led a band of rangers. Tomahawk enjoyed a long run of stories stretching until 1972, which introduced two generations of readers to the Revolution’s frontier warfare. Most of Tomahawk’s adventures were illustrated by Frederic “Fred” Ray, who brought historical accuracy to the work. (During his career Ray also documented Civil War uniforms and published books about Fort Ticonderoga and the Alamo.[12])

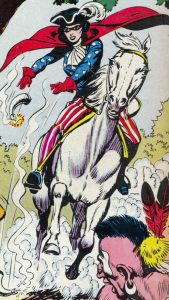

Superheroes had a resurgence of popularity in the 1960s, and so Tomahawk gained a costumed ally: Miss Liberty.

Miss Liberty was colonial nurse Bess Lynn, who disguised herself with a flag-inspired costume and enlisted an underground network of female patriots to help the Americans against the British.[13] After a series of missions, Miss Liberty died while fighting Hessian troops who were trying to steal the Liberty Bell. (The bell fell on Miss Liberty and killed her—a bizarre combat death, even for the comics.) Years later, DC Comics filled in Miss Liberty’s background and made her the ancestor of Liberty Belle, linking the War of Independence and World War II yet again.[14]

A few of these Revolution-fueled characters have been published into the current day, taking on new significances to fit the times. A new Liberty Belle has made appearances as a member of the Justice Society, providing continuity to the young superheroes of the twenty-first century. In an alternate reality, Uncle Sam recently led his super-hero team the Freedom Fighters against Nazis who won World War II and turned America into a dictatorship—a story that allowed its creators to examine the current state of American politics.[15] Comic books allow an endless reinvention of characters and ideas, and will doubtless continue to call back to the War of Independence for as long as the medium exists.

[1]Action Comics #1 had a cover date of June 1938 but was distributed in April. Otto Friedrich, “Up, Up and Away!! America’s Favorite Hero Turns 50,” Time (March 14, 1988): 68.

[2]Bob Kane with Tim Andrae, Batman & Me: An Autobiography (Forestville, CA: Eclipse Books, 1989), 45.

[3]Robert Kanigher, Ross Andru, and Mike Esposito, “The Bat Witch,” World’s Finest Comics #186 (DC Comics: August 1969), and “The Demon Superman,” World’s Finest Comics #187 (September 1969). In real life, Gen. Wayne did receive a land grant for his service, but it was in Georgia—nowhere near Batman’s Gotham City, which DC comics has placed in New Jersey.

[4]This was a pop-culture updating of the classic “king in the mountain” legend, in which heroes such as King Arthur, Owain Glyndŵr, and Charlemagne slumber until their nations’ time of greatest need.

[5]Mike Benton, Superhero Comics of the Golden Age (Dallas, TX: Taylor Publishing Company, 1992), 43.

[6]Les Daniels, Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World’s Greatest Comics (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1991), 37.

[7]Our FlagComics#2 (Ace Magazines: October 1941).

[9]Phil Sturm (script), Syd Shores (pencils), George Klein (inks), “The Spirits of Freedom,” U.S.A. Comics #1 (Marvel: August 1941).

[10]Chuck Winter, Boy Commandos #1 (DC Comics: Winter 1942-1943).

[11]Joe Samachson (script) and Chuck Winter (art), “Outpost in the Philippines!,” Star Spangled Comics #48. (DC Comics: June 1945).

[12]Ron Goulart, “Fred Ray,” The Comics Journal, March 8, 2013, http://www.tcj.com/fred-ray/.

[13]Dave Wood (script), Fred Ray (pencils and inks), “Miss Liberty—Frontier Heroine,” Tomahawk #81 (DC Comics: August 1962).

[14]Roy Thomas, ed., All Star Companion Volume Two (Raleigh, NC: TwoMorrows Publishing, 1996), 88, 185.

[15]Robert Venditti (scripts) and Eddy Barrows (art), Freedom Fighters, Volume 3 (DC Comics: 12 issues, February 2019-January 2020).

3 Comments

One of the more interesting bouts with the American Revolution was in Steve Canyon, who appeared as a cavalry officer and dealt with Benedict Arnold, knowing as a time traveler of Arnold’s treason but wary, because he wasn’t sure when it was he had time-traveled to; was he dealing with the traitor or the hero of Saratoga? Have you ever seen the wonderful Bill Mauldin series on the Revolution, modeled on his WWII Willie and Joe? The Revolution produced some genuine superheroes without super powers. Check out Capt. Allen McLane of Smyrna Delaware, New Jersey Privateer Captain John Mariner and South Carolina matron Rebecca Mott. Even though they were the enemy, It’s hard not to like Lord Charles Cornwallis and Capt. Johann Ewald.

I do love Ewald’s descriptions of the war!

Hope you guys are feeling better! We miss you up here!

This article took me back a bit. As a kid in England, I used to love American comics. Particularly the advertisements at the back for “x-ray specs” and “midget submarines” and the like. I spent ages saving up for a “footlocker” of 200 American Revolutionary War soldiers. The illustrations were brilliant, featuring grenadiers, cannons, dragoons, and Mohawk Indians. When they finally arrived, they were stamped “made in Hong Kong,” were two dimensional and so poorly manufactured as to be unusable. I think my dog destroyed the entire Continental Army by stepping on them. We should have sent him in place of Burgoyne. I found a photo of the ad on someone’s blog if you want to wander down memory lane.

http://flintlockandtomahawk.blogspot.com/2012/07/toy-revolutionary-war-soldiers.html