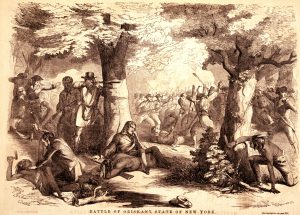

The coming of the American Revolution traumatized the North American frontier, and many old orders were left shattered in its wake. While historians often focus on the establishment of a new nation, few recognize the destruction of one of the continent’s oldest superpowers. The battle of Oriskany in New York’s Mohawk River Valley stands out for many reasons—it was one of the bloodiest days of the entire war, and one of the few battles that was made up almost entirely of North American participants. But perhaps its greatest legacy is the one discussed the least. On that day, the member nations of the Iroquois Confederacy waged war on one another for the first time, and the gruesome battle marked the beginning of a terrible civil war from which the People of the Longhouse would never recover.

The People of the Longhouse

From the beginning of the American Revolution the vast and mighty Iroquois Confederacy attempted to walk the fine line of neutrality. Made up of six member nations known respectively as the Haudenosaunee (People of the Longhouse), the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Tuscarawas, and Seneca each believed that the rebellion had the potential to disrupt their long-standing alliance with the British Empire. Although each had their own perspectives on the conflict, the Six Nations relied on their ancient system of governance to establish an official policy toward the two warring sides. Employing a pseudo-federal system, sachems representing each tribe met in council to negotiate terms and gather consensus, ultimately developing a confederacy-wide policy of absolute neutrality. From the earliest months of the war, even before the volleys at Lexington Green, the Iroquois Confederacy found themselves balancing on a tightrope of revolutionary proportions.

Tradition was paramount to the Haudenosaunee, but even the weight of history was not immune to the shifting political ground of revolutionary North America. Since the 1740s the Iroquois had been staunch allies with the Crown, and that agreement was instrumental to the British conquest of New France at the end of the Seven Years’ War. In the decade leading to the Revolution, though, some member nations had grown in prominence in the new British North America and a strong sense of localized autonomy had weakened the influence of the Great Council Fire. While the tribal elders stressed neutrality, the warriors of the western-most Seneca and Cayuga had flourished alongside the Redcoats, and Fort Niagara on Lake Ontario had become a royal headquarters on the frontier. Thus, with a prominent fort now on Seneca land and a wealth of trading opportunities, the renegade warriors had little interest in remaining impartial despite their tribal leadership’s wishes.[1]

The British were not the only ones to benefit from the waning influence of the Great Council Fire, and the Patriots found themselves with their own allies in the unlikeliest of circumstances. Just before the outbreak of the Revolution, Presbyterian minister Samuel Kirkland made the decision to abandon his life in New Hampshire and set up shop in the Mohawk Valley. As a test of faith and patriotic virtue, Kirkland dedicated his life to proselytizing and preaching in the heart of Iroquoia. As a general truth throughout the history of Colonial America, Haudenosaunee villages in the east tended to be more open to European interaction than their more autonomous brethren in the west; true to form, Kirkland found a welcome audience amongst the villages of the Oneida. While it appears simplistic, Kirkland fostered an intensely loyal bond with the Oneida as well as with the cause of liberty, and his connections became an asset for the struggling Continental Congress.

Despite the efforts of British and Patriot agents, unbeknownst to them the fabled “Longhouse” was suffering a catastrophe of its own. In January of 1777, an Onondaga sachem relayed to the commandant of Fort Stanwix, the primary post in the Mohawk Valley, that ninety of their most powerful chiefs had suddenly died. Clearly the result of an infectious disease, most likely smallpox, the Onondaga claimed that until new leaders could be chosen, “the Central Council fire is extinguished . . . and can no longer burn.” With this development, a startling revelation jolted the Iroquois world: with no council fire, there would be no centralized governing body to bind its member nations. Thus, the Haudenosaunee were free to act on their own in the larger saga of the American Revolution.[2]

By 1777, British operatives at Fort Niagara were successfully breaking the Iroquois’ tenuous neutrality and attracting most warriors to their side. At the same time the Oneida were quietly aligning themselves with the Patriot cause, and providing Kirkland with valuable intelligence as spies. The minister would relay those developments to Gen. George Washington, and soon became one of the Patriots’ most trusted agents on the frontier. Although the Longhouse remained intact, it was being pushed to a breaking point yet unseen in its centuries-old history.[3]

Into the Wilderness

By the spring of 1777 the state of the American rebellion was grim. After Gen. William Howe’s massive invasion failed to capture Washington’s Continental army in 1776, the new year brought a radical shift in Britain’s imperial policy toward their rebellious American colonies. From the perspective of the Court of St. James, the revolutionaries needed to be stamped out as quickly as possible; as seen in previous uprisings, radical ideas of political independence spread like wildfire if left unchecked, and once entrenched they were nearly impossible to remove. Guided by this urgent principle, British administrators anxiously announced an entirely new strategy for ending the war. It was wildly different than anything yet attempted, and served as a necessary reboot in their failing attempts at making peace in North America.

Only two years into the war, the British still viewed the Patriot movement as a uniquely New England phenomenon. While the war would eventually engulf the whole of the continent east of the Mississippi, officials believed that if the northeastern colonies could be physically separated from their colonial neighbors, the rebellion could be contained and eventually destroyed. The 315-mile-long Hudson River Valley served as the primary border separating New England from New York, and its total military occupation would achieve Britain’s overall objective. As the empire retained control of Canada and fully occupied New York City, the most critical components were already in place for launching such an expedition, and many in London felt that success was within reach.

In what would come to be known as the Saratoga Campaign, Gen. John Burgoyne would lead 8500 troops southward out of Quebec along the Lake Champlain-Lake George corridor and follow the Hudson all the way to Albany. Once there, Burgoyne hoped to cooperate with forces under the command of Sir William Howe in New York City. Finally, a third army would land on the shores of Lake Ontario led by recently-breveted Brig. Gen. Barrimore St. Leger. This final force would snake its way eastward through the Mohawk Valley capturing noted Patriot strongholds en route to their great union at Albany. It was an ambitious plan and timing was its most critical element.

The Mohawk Valley was a warzone. Since the Iroquois warriors declared for the Crown, local Patriots had regularly come under attack from raiding war parties and Loyalist rangers. Homes and farmsteads were destroyed, families were split, and the region disintegrated into a terrible civil war. While Redcoats and Continentals toiled in the Pennsylvania countryside, partisans on both sides arrested, harassed, and murdered their enemies in New York making it the most terrifying theater of the entire war. In the midst of the madness, Patriot forces maintained a series of forts along the Mohawk River, and these outposts became bastions of safety for the battered populace seeking refuge from the conflict. As Barry St. Leger’s Loyalists, Germans, and Indian allies descended upon the region, they were given the specific task of razing these fortifications before finally connecting with Burgoyne at Albany.

Upon St. Leger’s arrival on the shores of Lake Ontario, the whole of the Mohawk Valley was put on notice. Shortly after their landing, some 800 Iroquois warriors led by Joseph Brant, known amongst the Mohawk as Thayendanagea, greeted the British commander in a show of support. Brant had proven to be a loyal ally and vital asset to the royal war effort on the frontier, and his cooperation would be equally vital during the Saratoga campaign. Joined by other sachems from across Iroquoia including Cornplanter, Guyasuta (sometimes Kiasutha), and Sayenqueraghta, the expedition was a microcosm of the British Empire’s overall imperial vision. To the romantic onlooker, St. Leger’s column was precisely the multicultural, multiethnic response force desired to suppress the rebels that menaced their American colonies. While Albany was always the final rallying point, the post of Fort Stanwix was squarely in St. Leger’s proverbial crosshairs; recently captured by New York Patriots and presumptuously renamed “Fort Schuyler” after the commander of the Northern Department of the Continental army, the British were anxious to reclaim the site. By July 14 St. Leger began to assemble his column at Oswego, and on July 26 his awesome force began their march eastward.

The Patriots of Tryon County, New York had grown accustomed to defending their own territory, and were more than comfortable taking their defense into their own hands. Led by Nicholas Herkimer, the Tryon County militiamen had received warnings of a potential British attack on Fort Stanwix from their Oneida allied scouts; on July 30 the spies discovered that St. Leger’s men were indeed marching on the post. With this vital intelligence the Oneida nation and sachems like Han Yerry cemented their place as a loyal partner in the cause of freedom. By August 2 St. Leger’s column had reached Fort Stanwix near modern Rome, New York, and by nightfall it was fully under siege. With these developments, the men of Tryon County and the warriors of the Oneida rallied 800 men to liberate the fort. For the Americans inside their only hope was the joint Patriot-Oneida force under Herkimer and Han Yerry.

The Battle of Oriskany

From the nearby Oneida village of Oriska, Herkimer attempted to reach out to the besieged Fort Stanwix. Now the head of a major relief column, Herkimer instructed three runners to deliver a message to the commandant of the post, Peter Gansevoort, informing him of his movements. According to Herkimer’s wishes, Gansevoort was to fire his cannons in three successive bursts upon receipt of the message, and promptly sortie his men out from the post to join with the approaching militiamen. It was a bold maneuver designed to break St. Leger’s siege of the fort, but Herkimer’s instructions did not reach Gansevoort in time. Instead his scouts were delayed while sneaking through the British lines, and Herkimer’s message remained undelivered. Overcome with urgency, on the morning of August 6 the Tryon County militiamen and their Oneida allies elected to liberate the post, with or without the cooperation of the men inside.

Although he was in a foreign land and deep in the American frontier, Brig. Gen. Barry St. Leger remained one step ahead of his opponents. The warriors allied with the British were the eyes and ears of the forests, and Molly Brant, the sister of the Mohawk war chief Joseph Brant, played a crucial role in St. Leger’s intelligence gathering operation. With Fort Stanwix surrounded, the commander received valuable intelligence from Molly Brant that a Patriot force was marching westward presumably to rescue the garrison inside the post. With the news of Herkimer’s advancing column, the commander ordered the Loyalists of the King’s Royal Regiment of New York and Butler’s Rangers to intercept the Tryon County militia; Joseph Brant and 400 Iroquois warriors joined in anticipation of the fight to come.

On the morning of August 6, Herkimer’s Tryon County militiamen and Han Yerry’s Oneida warriors trekked westward toward their target. As per the commander’s orders, the militia marched in two separate columns. The Oneida warriors marched alongside the columns as flankers, and another party served as the vanguard marching ahead to gather any actionable intelligence that could serve the New Yorkers. Herkimer strode near the front of his men on a white horse, and his status was clear as the overall leader of the Patriots; less so his Oneida counterpart. In the strictest sense Han Yerry had no authority to order his fellow warriors into battle—he was merely a first among equals. The respect afforded him was garnered from past bravery, not an awarded commission or inherited title. Instead of fighting forHan Yerry, the Oneida merely followed his example and fought with him. As such he made no effort to distinguish himself amongst his peers as their marched, a contrast that was only one of the many seen in a war that brought so many alternative worldviews onto the same battlefield. At his side was his wife Tyonajanegen (meaning “Two Kettles Together”) and his son Cornelius. As the joint Patriot-Oneida force marched within six miles of the besieged Fort Stanwix, the rough road and dense forests provided ample cover for any would-be attackers waiting in ambush, and the potential for danger awaited around every bend.

Unbeknownst to the approaching force, they were walking into a trap. Earlier that day Joseph Brant and his Iroquoian warriors positioned themselves on a deep ravine that bisected the Albany-Oswego Road. Using his previous knowledge of the ground, Brant relied on the ancient methods of tactical ambush to surprise his enemies, and with any luck, destroy them before a general battle could begin. According to his plan Brant would arrange his Seneca and Cayuga warriors along both sides of the main road in a silent position allowing the Patriots to march past them. As the unsuspecting column climbed out of the ravine, they would discover Sir John Johnson’s Royal Yorkers positioned across the main road. When Herkimer’s men engaged the Loyalists, Brant would spring his trap in the ravine and sever the marching column, creating utter chaos on the road and swarming their enemies. With the right combination of patience and fury, the great showdown in the wilderness would be no contest. Although he could not control all of the warriors on hand, Brant relied on other prominent war chiefs to keep the younger, more rambunctious warriors under control until the time was right. Seneca warriors such as Guyasuta, Cornplanter, and Sayenqueraghta were instrumental in selecting the ambush location, and Brant trusted that they could manage the oncoming assault as well.[4]

At 10 AM the Patriots had reached the ambush site. As planned, the warriors remained silently hidden as the front of the column passed by along the Albany-Oswego Road. Eyewitness accounts place Nicholas Herkimer near the front of his men, so much so that he was able to guide his horse fifteen feet into the ravine and climb back out the other side without ever noticing the enemy war party that quietly surrounded him. With only the head of the column through the ravine, the sachems were undoubtedly surprised to hear shots ringing out from the rear. With the Patriots in their grasp it appeared that some of the overzealous warriors fired on Herkimer’s men too soon, and the battle began in earnest with nearly three quarters of the Patriot column yet to enter the kill zone.

By the time that Herkimer was able to turn to investigate the nature of the popping muskets, the ambush was already taking effect. Despite its premature initiation, Col. Ebeneezer Cox, the head of the first regiment of the Tryon County militia, was dead. Soon after, Herkimer was struck through the thigh and his horse killed. Herkimer was badly wounded but refused to leave the battlefield; his men sat him against a tree and he directed the battle from that spot, even managing to smoke his pipe in the process. As was the case in most frontier battles, the engagement was chaotic. Rather than armies aligned in traditional formation, the fighting appeared more like a series of independent duels and brawls. When Brant’s warriors left Fort Stanwix quickly, many failed to bring muskets and powder. Instead, they settled the matter with hand to hand combat. One of the war chiefs on hand was Governor Blacksnake of the Seneca, who recalled: “they had 3 cannon and we have none, But Tomehawks and a few guns amongst us, But agreed to fight with Tomehawk Skulling Knife.”[5]

The fighting was hotly contested, and the Patriots were reeling. As the battle progressed, the British-allied Iroquois took full advantage of their enemies’ weaknesses. After the Tryon County militiamen fired their muskets, the warriors would spring from cover to attack with knife and tomahawk. By 1777 the Iroquois were well-versed in traditional, European-style battlefield tactics, and they knew to wait for the flashing muzzle as a signal to attack. As the frontiersmen tried in vain to reload their firearm, they were struck down by a pouncing Iroquoian warrior. Despite these deficiencies the Patriots still fared better than their colleagues from Virginia and New England; a life on the frontier had schooled them in Indian warfare, and they comfortably discarded their muskets to fight with blades of their own.

Mother Nature cares little for the politics of man, but on August 6 she intervened on the Patriots’ behalf. At midday, a thunderstorm suddenly appeared and soaked the battlefield. The combat stopped for an hour, and afterwards both sides tried to capitalize on the break. After the rains subsided, Herkimer was able to rally his men out of the ravine and position them on the high ground. Likewise, the British commander Johnson instructed his men to turn their jackets inside out as a means of confusing the Patriots. The ruse nearly worked, but due to the intensely localized nature of the battle neighbors soon recognized one another and alerted their superiors as to the apparent scheme.

To fend off the attack in the second phase of the battle, the wounded Herkimer instructed his men to fight in pairs. As one man loaded and reloaded his musket, the other would fire on the charging enemy. This tactic meant that no soldier would ever be without a loaded weapon, and served to negate the Indian strategy of attacking during the reloading process. One of the most spectacular scenes of the battle was of the Oneida sachem Han Yerry and his wife Tyonajanegen—as he fired alongside his Patriot allies, Two Kettles Together made sure that he had a fully charged musket at the ready to fend off the next wave of Seneca, Cayuga, and Mohawk attackers. As the day wore on, tradition holds that she joined the fight as well.

Ironically, the turning point of the battle did not occur on the field itself. Six miles away at Fort Stanwix, the commandant Peter Gansevoort finally received Herkimer’s lost intelligence from the previous day. Gansevoort ordered the sortie that was requested, but not to the battle site. With most of the warriors now fighting at the ravine, Gansevoort’s troops immediately began to plunder the vacant camp of the British-allied Indians. When the warriors sparring with Herkimer caught wind of the raid, they immediately fled from the battlefield to save their valuable winter stores that had been left unattended. When the British-allied Iroquois fled, Johnson and Brant lost most of their manpower, and gave the Patriots a timely window to flee from the battle. As Blacksnake recollected years later, “the Blood Shed a Stream Running Down on the Decending ground.”[6]

Bloody Creek

War is not a game. It does not play by the traditional rules of a game, and therefore cannot be evaluated as such. One of the most challenging aspects of the Battle of Oriskany remains the determination of a “winner.” Body counts are a means of “keeping score,” but not a good one. Holding the field remains another traditional axiom of victory, but it alone does not tell the whole story. Frontier warfare was brutal in its suddenness and often ended in indecisive stalemates. For this reason, the frontier battles of the war are often overlooked, but in doing so a critically important part of the Revolutionary drama is missed.

The British and Iroquois warriors fled the battlefield first, but the damage that they inflicted was far greater than that of their opponents. While the Patriots retreated on their own terms, their original goal of liberating Fort Stanwix was a failure. Instead of continuing westward, Herkimer ordered his men to return east toward Fort Dayton. He died from his wounds ten days later. As the British and allied warriors stopped the Tryon County militiamen and the Oneidas from reaching their destination, the battle known as “Bloody Creek” has tentatively been labeled a victory for the Crown.

In frontier warfare the traditional battle lines are blurred in more ways than one, and in most cases engagements rarely have “winners” that are readily identifiable. Considering the terrible costs of the Battle of Oriskany, it is truly difficult for either side to appear triumphant. Estimates state that the Patriots suffered nearly fifty percent casualties during the battle, while the British lost roughly fifteen percent.[7]

The losses on the Native side will likely never be known, but the carnage was undeniable. Accounts vary, but most tally Indian losses at sixty-eight warriors, and a staggering twenty-three war chiefs. Blacksnake recalled “There I have Seen the most Dead Bodies all it over that I never Did see, and never will again.” Another witness, Continental scout Frederick Sammons, wrote: “I befell the most shocking sight I had ever witnessed. The Indians and white men were mingled with one another, just as they had been when death had first completed his work. Many bodies had also been torn to pieces by wild beasts.” Many speculate that the engagement was one of the single bloodiest days of the entire war.[8]

The war in the Mohawk Valley continued. In response to the siege of Fort Stanwix and the loss at Oriskany, Maj. Gen. Benedict Arnold led a force of 700 men to liberate the post. He never arrived, but misleading intelligence spread by allied warriors thoroughly convinced General St. Leger that Arnold was on his way with 3,000 men. By the time Arnold began his march, he received word from a joyous Gansevoort that the British had abandoned their assault on Fort Stanwix. In one of the master strokes of the war, the Patriot parties would all meet once more at Saratoga. By October, Gen. John Burgoyne’s great invasion came to a screeching halt.

A Place of Great Sadness

The Battle of Oriskany plays a terrible role in the oral traditions of the Haudenosaunee. Known among themselves as “a place of great sadness,” the fight in Upstate New York stands as watershed moment in the history of the Iroquois. With the council fire extinguished, the six member nations of the Iroquois Confederacy acted on their own during the American Revolution. When they met on the battlefield at Oriskany, it marked the end of a centuries-old system that had ruled the American Northeast. In the wake of the battle, British-allied sachems delivered a tomahawk to their Oneida brethren. Unthinkable only a year earlier, the reception of the now infamous weapon represented a formal declaration of war.[9]

As the traditional story of the American Revolution played out between the Continentals and Redcoats, the forgotten Iroquois civil war ravaged the frontiers. In the wake of Oriskany Joseph Brant’s warriors raided and destroyed the Oneida village of Oriska. In retaliation, the Patriot-allied Oneida razed Tiononderoge, Canajoharie, and eventually Fort Hunter Mohawk. The inter-tribal conflict would go on until 1779, when George Washington ordered the joint forces of James Clinton, John Sullivan, and Daniel Brodhead to march their armies into Iroquoia. The 1779 campaign burned villages, fields, and stores leaving the region utterly devastated.

By 1783 the world witnessed the foundation of a new American nation, as well as the destruction of another.

[1]Timothy J. Shannon, Iroquois Diplomacy on the Early American Frontier (New York: Penguin, 2008), 185.

[2]Speech of the Oneida Chiefs, January, 19, 1777 as quoted in Barbara Graymont, The Iroquois in the American Revolution (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1972), 113.

[3]Colin G. Calloway, The American Revolution in Indian Country (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 129.

[4]Michael O. Logusz, With Musket and Tomahawk (Philadelphia: Casemate, 2012), 2: 123.

[5]Blacksnake to Benjamin Williams, as quoted in Thomas S. Abler, Chainbreaker: The Revolutionary War Memories of Governor Blacksnake (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2005), 128.

[7]Isabel Kelsay, Joseph Brant (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1984), 205-209.

[8]Ibid. and Frederick Sammons as quoted in Logusz, With Musket and Tomahawk, 2: 171.

[9]Recollections of Iroquois Visitors as quoted in Joy Bilharz, Oriskany: A Place of Great Sadness (Boston: Northeast Region Ethnography Program, National Park Service, 2009), 93.

13 Comments

Excellent article!

It seems from your account that the Native Americans viewed the Euro-Americans as independent from the British well before the Euro-Americans realized themselves!

Gene,

I would certainly say so. It was a long standing view that Indian nations each had their own unique identity; even amongst the Iroquois they saw themselves as six separate ethnic-national groups. The notion of “Indian” and “white” was largely foreign and only in its infancy at this point. They were much more aware of the euro-diversity in Colonial America than we are now. They saw “colonists” as Quakers, English, Scots-Irish, Swedes, Dutch, Germans, etc. They were also keenly aware of what distinguished a Massachusetts man from a Pennsylvanian or New Yorker.

Timely article Brady. Is it just me or does the death in a short period of time of ninety leaders of the Iroquois Confederacy seem a bridge too far. Ninety leaders are dead and how many tribesmen and women and children as well? This seems out of normal proportion to me which raises the question did this happen on purpose somehow? The subsequent raid on the Confederacy by the Sullivan expedition must have devastated the Native American communities and left the Confederacy in tatters. All in all too typical of what happened to native tribes as they encountered the white settlers. Has anyone looked at the Details of what happened to the ninety dead leaders?

Steve,

Epidemic disease was an unfortunate reality for Native peoples. It came in waves and was ever present. I have not seen any evidence (in this case) to note that it was the result of some kind of germ warfare. Of course that did happen in other instances.

Really great article. Some scholars have called Oriskany the “Little Bighorn” of the American Revolution, considering the way Herkimer and his men were encircled in the woods.

Thanks George,

It was a terrible battle that doesn’t compute with most peoples’ casual view of the war. It muddies the waters, but as historians it’s our job to dive in and make sense of it all. I would suggest a visit to the battlefield if you ever get the chance. Just like Little Bighorn you can still see how the terrain stands unchanged and really tells the story.

Thanks for this informative, well-structured, and well-written article, Brady. Question: In the immediate aftermath of the war, did the victors grant preferential treatment to the Oneida or show gratitude?

Thank you Rand,

The postwar was a mixed bag for the Oneida. In the wake of the battle the British-allied Iroquois destroyed much of the Oneida homeland in retaliation. Washington recognized their value and invited them to live amongst the army at Valley Forge, and many Oneida warriors acted as scouts and auxiliaries for the remainder of the conflict. After the war Congress paid reparations to the Oneida for their losses, but gradually the state of NY began to claim large tracts of land carved out from the Oneida homeland.

I found your article very interesting and the facts told clearer than some other writings I have read. My ancestor Thomas Morgan, from the Johnstown, New York area, is said to have died on the St Leger Exoedition, but I have never been able to find the proof.

Great article, Brady. Certainly highlights the complexity of the Revolution. This civil war within a civil war is an aspect I had not considered before. I wonder how Iroquoia might have fared had the nation remained united and neutral. Could neutrality even have been possible? Probably not, but we can only speculate.

Derrick,

They really committed to neutrality from the outset, but it just was not feasible. The biggest issue that the Iroquois faced was that their governmental system had been steadily collapsing since the Seven Years War. By 1777 they had lost the faith of their member nations, and the confederacy fell to pieces rather quickly.

I am in no way an expert, but this story reminds me of the role Brant played in the battle of Minisink in Orange County, NY, in 1779, when members of my family were killed by either the Indians or Tories or both. It has been fascinating to read about these battles on the western side of the Hudson. I just had no idea of the important Indian role, although with 20/20 hindsight it certainly makes sense. Meanwhile I have had the opportunity this last year to help index the records generated at the camp at West Point—from payroll to party supplies for the visiting French officers to courts martial reports. Fascinating. It is like being there.

Really wonderful battle site to visit!