A visitor to Williamsburg prior to the outbreak of the Revolutionary War would have discovered a city of just 1,900 inhabitants, roughly 900 of whom were white and free and the remaining 1,000 black and mostly enslaved.1 These were the year-round inhabitants who lived in the several hundred wooden and brick dwellings that sat upon the city’s mile-long main street (Duke of Gloucester) and its several side streets.2

With no significant manufacturing or trade to speak of and limited water access to the James and York Rivers, Williamsburg’s prosperity depended on its status as Virginia’s capital. The business of governing attracted many visitors to the city and they arrived eager to conduct political, judicial, and commercial affairs. When sessions of the colonial legislature (House of Burgesses), the courts and the merchant exchange were held, the city’s population swelled to more than double its normal size. Most of this activity was concentrated in the eastern part of Williamsburg, between the capitol and palace green.

At the east end of Duke of Gloucester Street stood Virginia’s capitol building, a fine three story brick structure built in 1751 upon the foundation of the original which had burned several years earlier. Virginia’s legislature met regularly in the capitol, as did the governor’s privy council (his advisors) and the General Court (which heard all felony cases brought forth in Virginia).

Merchants and planters from all parts of Virginia, as well as some from Maryland and North Carolina, met outside, in the shadow of the capitol building several times each year to transact business. A quarter of a mile to the west, near the center of Duke of Gloucester Street, sat the courthouse, used by both the city of Williamsburg and James City County. Meeting regularly throughout the year, the courthouse and nearby open air market attracted a number of visitors.

With so many people visiting Williamsburg on a regular and steady basis, it is not surprising that a number of fine taverns were established to provide food, drink, and lodging for the city’s many guests. The Raleigh and the King’s Arms (across the street from the Raleigh) were popular taverns as were those operated by James Anderson (formerly Weatherburn’s) and Christiana Campbell (located on the east side of the capitol building). In all, twelve taverns were in operation in Williamsburg on the eve of the Revolutionary War and there were plenty of visitors to generate revenue for all of them.3

Filled with burgesses, planters, merchants, and common folk from throughout Virginia, the taverns were convenient places to transact business and learn the latest news. The Raleigh Tavern stood out as the gathering place for Virginia’s leaders following the Townshend Duties of 1767 and the Intolerable Acts of 1774. In the Raleigh’s grand Apollo room the likes of Peyton Randolph, Speaker of the House of Burgesses and Williamsburg’s most prominent resident, colonial treasurer Robert Carter Nicholas, also a prominent city resident, Patrick Henry, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, George Wythe, Richard Henry Lee and many others met to discuss and debate Virginia’s response to the unconstitutional taxes of the Townshend Duties and the unconstitutional policies of the Intolerable Acts.

Williamsburg’s many taverns were also places for entertainment, especially when the city was bursting with visitors. A French traveler to Virginia in 1765 recorded his impression of Williamsburg at a time when both the House of Burgesses was in session and scores of merchants had gathered to conduct business. Invited by several gentlemen to a tavern to spend the evening gaming, an activity observed the Frenchman that was rampant in Williamsburg, he complained in his journal after the experience that,

Never was a more Disagreeable place than this at present. In the Daytime people hurrying back and forwards from the Capitol to the taverns, and at night, Carousing and Drinking in one Chamber, and box and Dice in another, which Continued till morning Commonly. There is not a publick house in Virginia but have their tables all battered with the boxes which shews the Extravagant Disposition of the planters.”4

Apparently, not every guest appreciated the entertaining nature of Williamsburg’s taverns.

Although politics and the law were the primary economic drivers of Williamsburg’s economy, its large (relatively speaking) “urban” population, the surrounding populations of York and James City Counties, and frequent visitors from even further away created enough economic demand to support a variety of artisans and merchants in the city. In 1775, twenty-seven store keepers and merchants, six apothecaries, six tailors, six milliners, six wigmakers, barbers and hair dressers, and three shoemakers made a living in the city.5 Several carpenters, contractors, cabinet-makers, saddlers, coach makers, and wheelwrights also operated businesses in Williamsburg as did several silversmiths and jewelers, two blacksmiths and a gunsmith.6 It was these inhabitants of Williamsburg, along with their families and servants and slaves that made up the bulk of the population of the city. Some of these tradesmen even served in the governance of Williamsburg through the Common Hall, a sort of unelected city council formed when the city was chartered in 1722.

The Common Hall: Williamsburg’s Governing Body

Williamsburg’s Common Hall consisted of a mayor, a recorder (clerk/lawyer), six aldermen, and twelve common councilors. The original members of the Common Hall were appointed by the King and served for life during good behavior. When a member of the Common Hall died or resigned (either alderman or councilor), the vacancy was filled by the aldermen. The city mayor was elected annually by the Common Hall from among the aldermen.

Although there was little that was democratic about the selection of Common Hall members, the urban population from which they were drawn meant that the members of the Common Hall were more economically diverse than those of the House of Burgesses (which was dominated by Virginia planters). Several members of the Common Hall were skilled artisans and others were merchants, while a few doctors and lawyers were also members.7

On the eve of the Revolutionary War in 1775, the mayor of Williamsburg was John Dixon, printer and publisher of one of the three Virginia Gazette newpapers that appeared in the capital every week. City aldermen in 1775 included Attorney General John Randolph, Thomas Everard, a lawyer and court clerk for the county of York, John Blair Jr., another lawyer, James Cocke, a prominent merchant, and Dr. James Blair and Dr. William Pasteur, both physicians.8

Some of the members of the Common Council in 1775 included John Tazewell, a lawyer, James Geddy, a silversmith, Alexander Craig, a saddler, Benjamin Powell, an undertaker (building contractor), and Robert Miller, a merchant. Several other counselors remain unidentified.9 All of these men formed the Common Hall, which was charged with addressing the local concerns and problems of the city’s residents.

Virginia’s Leaders on the Eve of War

As the seat of government for the entire colony of Virginia, Williamsburg was also the residence of some of the colony’s most important political leaders. On the eve of the Revolutionary War this included the royal governor, John Murray, the 4th Earl of Dunmore. Lord Dunmore, who reluctantly relinquished the post of governor in New York to assume the post in Virginia in 1771, was a Scotsman with a fiery temper. Destined to be the last royal governor of Virginia, he was joined in Williamsburg in February 1774 by his wife Charlotte and six of their seven children (their youngest son remained in Scotland). While Dunmore’s official residence, the Governor’s Palace located at the end of Palace Street, may not have matched the standards that Lord Dunmore and his family were accustomed to in Scotland, it was arguably the most elegant house in Williamsburg, if not all of Virginia, and dozens of servants (some paid and others indentured) as well as a great number of slaves worked hard to serve the governor and his family’s every need.10

While Lord Dunmore represented the chief executive authority in the colony (in the name of King George III) the leading legislative figure in Virginia was the Speaker of the House of Burgesses, Peyton Randolph. Speaker Randolph lived with his wife, Elizabeth, and twenty-seven household slaves on Nicholson Street, within a short walk of the Governor’s Palace and an even shorter walk from the county courthouse and market square, which were situated directly across from Randolph’s house in the center of Williamsburg. Trained in the law in London, Peyton Randolph had devoted most of his adult life to public service, first as attorney general and then as speaker of the House of Burgesses (representing the city of Williamsburg in the assembly). The high regard in which Speaker Randolph was held among all Virginians was shared by the delegates assembled in Philadelphia at the First Continental Congress in 1774. Randolph was selected by these men to preside over the Congress in September of 1774 and again in May of 1775 at the Second Continental Congress.11

John Randolph, the attorney general of Virginia, was Peyton Randolph’s younger brother. He too lived near market square, within view of the courthouse, but on the other side of it, on what is now South England Street. He followed a similar path to his brother, studying law in London and becoming the Clerk to the House of Burgesses in 1752. John Randolph replaced his brother as attorney general upon Peyton’s selection as speaker of the House of Burgesses in 1766. He also served in the House of Burgesses as the College of William and Mary’s representative and he was an alderman for the city of Williamsburg. Although Peyton and John Randolph shared a strong commitment to public service, their views diverged significantly regarding the growing political dispute with Parliament. Unlike his brother Peyton, who was politically moderate in his opposition to Parliament, John Randolph argued forcefully against actions by the colonists that challenged parliamentary authority. He viewed the First Virginia Convention and the First Continental Congress, both held in 1774, as extralegal and thus illegal assemblies and he urged Virginians to refrain from disloyal actions that would provoke parliament and the King.12

Robert Carter Nicholas, the treasurer of Virginia, was viewed by all who knew him as a pious, even-tempered man. On the eve of the Revolution, Nicholas lived on Francis Street, across from the powder magazine and courthouse, with his wife and ten children. Nicholas had attended William and Mary and possessed land outside of Williamsburg from which he derived a generous income. He was elected to the House of Burgesses in 1756 as a representative from York County (living at the time in the house adjacent to the governor’s palace). In 1761 Nicholas gave up his seat in the assembly and relocated to Francis Street, which was situated in James City County. He returned to the House of Burgesses in 1766 as a representative from James City County and was appointed that same year as treasurer of the colony at the death of the former treasurer and speaker of the House of Burgesses, John Robinson. It was as treasurer that Robert Carter Nicholas served Virginia during the Revolution.13

George Wythe, a lawyer who many in Virginia believed possessed one of the colony’s best legal minds, resided in a grand brick building on the palace green within sight of the governor’s palace. When he was not tutoring the likes of Thomas Jefferson in the law or arguing cases before the general court, Wythe served his fellow citizens of Williamsburg as a city alderman and mayor, responsibilities he surrendered in 1773 upon his resignation as an alderman. Like the Randolphs and Robert Carter Nicholas, Wythe also held an important post in the colonial government in 1775, serving as clerk of the House of Burgesses. In this position, Wythe assisted burgesses with their bills and resolutions, something his keen legal mind was well suited for. Wythe had served as a burgess himself during the early years of the dispute with Parliament and was well-versed on the troubles. His experience and vast legal knowledge would lead to his selection as a delegate to the Continental Congress in 1776. Among Virginia’s signers of the Declaration of Independence, George Wythe’s name comes first, a testament to the high regard his fellow Virginians had for him.14

These five men (Lord Dunmore, Peyton Randolph, John Randolph, Robert Carter Nicholas, and George Wythe) held the principle governmental posts in Virginia in 1775 and wielded great influence in the governance of the colony. They were frequently joined in Williamsburg by such notable figures as Patrick Henry, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Richard Henry Lee, and many other burgesses who represented the freeholders of Virginia’s various counties in the House of Burgesses.

And thankfully, we too can visit Williamsburg and see the city largely as it was in the 1770s, thanks to the efforts of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and its many talented employees. You many even encounter some of the very people mentioned above as well as many others who contributed significantly to America’s story. At the very least you will walk in the footsteps and among the shadows of one of the most important cities in the American Revolution and thus, in American History.

1“Table 2.7: Population and Estimated Food Requirements in 1775,” L. Walsh, A. Martin, and J. Bowen, Provisioning Early American Towns, The Chesapeake: A Multidisciplinary Case Study: Final Performance Report(Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1997), 62.

2General Description of Williamsburg: Compiled from Primary Source Material and Chronologically Arranged, Department of Research and Record Colonial Williamsburg, 1942, 15, 17.

3James H. Soltow, The Occupational Structure of Williamsburg in 1775(Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1990), 5-6.

4Journal of a French Traveler in the Colonies (New York: American Historical Review, 1921), 741-743, www.loc.gov/item/ca33000046/.

5Soltow, The Occupational Structure of Williamsburg in 1775, 5-6.

7According to the 1722 Charter that established the Common Hall, its members were to meet on St. Andrews day to elect a mayor and fill any vacancies in the Common Hall. A survey of the Virginia Gazettes for the first week of December from 1766 to 1776 produced the list of counselors, aldermen, and mayor for 1775.

8A survey of the Virginia Gazettes for the first week of December from 1766 to 1776 produced the list of counselors, aldermen, and mayor for 1775.

10John E. Selby, Dunmore,(Williamsburg, VA: Virginia Independence Bicentennial Commission, 1977), 10-19.

11Inventory and Appraisement of the Estate of Peyton Randolph Esq. in York County taken January 5th, 1776.

12William J. Van Schreeven and Robert L. Scribner, eds., Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1973-1977), 1: 204-205.

6 Comments

As a follow up, 245 years ago this week (June 1775) Williamsburg was very much on edge over actions taken by the royal governor (Lord Dunmore and the gunpowder in the magazine) as well as news from Massachusetts. Sadly, when I walked through town this morning and last night I saw a rare sight, shutters closed in many of the buildings. (The last time I saw this was when a hurricane was expected).

This is regrettably a necessary precaution given the turmoil of this past week, but the sight made me wonder if the inhabitants 245 years ago might not have done the very same thing in concern over Lord Dunmore carrying out his threats to burn the town. There had already been several false alarms of armed British sailors and marines approaching town, and on June 8th the situation escalated significantly with the flight of Lord Dunmore and his family from the palace in Williamsburg to a British warship in the York River. By the end of the month Dunmore would complain to British authorities that Williamsburg resembled an armed camp (of militia volunteers from surrounding counties). There was little hope of reconciliation after his flight. Each side dug in and Virginia progressed, ever so slowly but steadily towards war.

Very enjoyable (and educational) article, Mr. Cecere.

Like many of us, I’ve visited Williamsburg many times and have always found the city, and surrounding area, very beautiful and interesting.

On my first visit many years ago, I became a fan of George Wythe. Thank you for the information regarding him and the others on the eve of revolution.

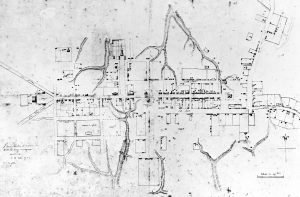

Thoroughly enjoyed this piece, Mr. Cecere. The perfect historical guide to consult again whenever I’m able to return to the town for a visit. It really personalizes the movers and shakers at that moment in time and puts life into some of the buildings I only had the chance to glance at when I was there briefly a few years ago. My wife (who for years hauled some of her seventh-grade social studies students from Denver to see this historic town) and I had a pleasant stroll on the William & Mary campus one late evening; so interesting to see the map in your article showing those diagonal walkways already in place.

When I read your words I am transported back in time and I can see these amazing people working, enjoying life, preparing for independence! Thank you! I love your writing!

Very well written—and interesting material ref. Colonial Williamsburg—a must read for all—particularly those in school—studying or about to study Colonial Williamsburg and the American Revolution. H.T.PAISTE, III 6/3/20

Excellent article Mr. Cecere, thank you. I grew up in Williamsburg and spent 5 years marching through these historical streets as a snare drummer in the Colonial Williamsburg Fifes and Drums. So many wonderful childhood memories, to include hiding in the basement of the George Wythe house on occasion. I had not seen the 1782 map before, so thank you for including it!