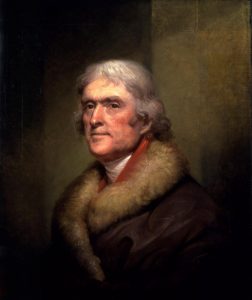

In 1813, Thomas Jefferson received a letter from Marguerite Brazier Bonneville, a French emigre and Thomas Paine’s former caretaker. Bonneville asked the former president if she could publish Paine and Jefferson’s correspondence. Paine had left most of his estate including all of his personal papers to her in his will when he died in 1809. Jefferson declined. “While he lived,” he replied, “I thought it a duty, as well as a test of my own political principles to support him against the persecutions of an unprincipled faction [the Federalist Party].” Jefferson indicated that he did not wish to disturb his “tranquility.” And he continued: “It is my wish that they should not be published during my life, as they might draw on me renewed molestations from the irreconcilable enemies of republican government. I would rather enjoy the remainder of life without disturbance from their buzzing.”[1]

Jefferson’s words to Madame Bonneville probably would not have surprised Paine. Still, they surely would have stung. In 1792 Jefferson had written to Paine after receiving copies of his second volume of Rights of Man, sent to Jefferson by way of President George Washington while Paine was in Paris:

Our people, my good friend, are firm and unanimous in their principles of republicanism & there is no better proof of it than that they love what you write and read it with delight. The printers season every newspaper with extracts from your last, as they did before from your first part of the Rights of Man . . . Go on then in doing with your pen what in other times was done with the sword: show that reformation is more practicable by operating on the mind than on the body of man, and be assured that it has not a more sincere votary nor you a more ardent well-wisher than Yrs, &c.[2]

What happened to some of the correspondence between the two men will never be known, because Paine’s papers were lost forever. The papers were left upon Marguerite’s death to her son, and Paine’s godson, West Point graduate, soldier, and explorer Benjamin Lewis Eulalie de Bonneville. His adventures in the American West were made famous by the writings of Washington Irving in the 1830s. Unfortunately, Capitan Bonneville’s attempt to store Paine’s papers in a safe place failed when the barn in Missouri where he left them burned down while he was away. At least, that is the story as told by his surviving widow many years after her husband’s death.

Fortunately, much of Paine and Jefferson’s correspondence survives, at the Library of Congress in its collection of Jefferson’s Papers, and at Monticello. And among those materials are letters between Jefferson and Paine that reveal a mutual interest in expanding the American frontier. The letters, several written by Paine to Jefferson, support the president’s decision to acquire the Louisiana Territory.

Interestingly, Paine never ventured further west than Valley Forge and the Schuylkill River. As for Jefferson, though he traveled up the eastern seaboard and, like Paine, spent time in Europe during the formative years of America’s constitution-building after the Revolution, he never went further west than his native Virginia. But all one has to do today to learn of Jefferson’s fascination with the American frontier is to visit Monticello and walk through the front door to discover the western artifacts and décor in the Entrance Hall.

Jefferson’s interest in all things American West—its geography, flora, fauna, fossils, and people, especially native Americans—was unmatched by early American presidents. He was, as Joseph Ellis stated, “in spirit, if not in fact . . . a westerner.”[3] And although Paine may not have possessed the same fascination, he too was keenly aware of the potential the largely unexplored western portions of the continent offered for building a strong, independent nation.

Both men have been identified with the nascent idea of American exceptionalism, the idea that the American character, and the nation’s immense territory, were unique, and gave Americans a rare opportunity unavailable to the territorially and culturally bound nations of old Europe.

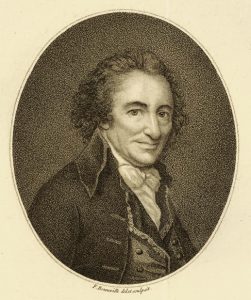

After a hiatus in Europe of fifteen years, Paine, the famous author of Common Sense, the American Crisis and the Rights of Man, returned in 1802 to America with the help of Jefferson’s encouragement. Jefferson even offered Paine the opportunity to return on a national ship, much to the consternation of the Federalist Party that had come to detest Paine.

Paine had become persona non grata in America for several reasons. In the 1790s he wrote his famous (or infamous to many Americans) theistic work The Age of Reason while in France during the Reign of Terror. In two volumes he attacked all organized and revealed religion, including Christianity. The work caused a sensation in America, a very negative one, and caused Paine much grief for the rest of his life.

Adding insult to his own injury, Paine publicly attacked George Washington in a bitter letter he published in the American press, blaming the president for his seeming indifference to his old Revolutionary friend’s pleas to help get him out of prison in France during the Reign of Terror. Paine had been caught up in the French Revolution and elected to the French National Assembly. But as a moderate who publicly decried the decision to behead Louis XVI, he was imprisoned by Robespierre during the revolution’s most bloody period and awaited what he assumed would be a similar fate. He got lucky.

James Monroe, another Revolutionary friend and at the time and an envoy to Paris, succeeded in getting Paine out of the Luxembourg prison. But Paine never forgave Washington. Washington ignored Paine’s letter, and the two men never corresponded again.

For a decade after Paine’s attack on Washington, Jefferson did not reply to Paine’s letters either. But upon his return to America, Jefferson maintained a cordial relationship with his old Revolutionary friend, at least for a while.

After landing in Baltimore, Paine went directly to Federal City. He had declined an offer from Jefferson to return on a government frigate Jefferson had suggested, because the Federalist press charged that Jefferson was sending the ship, the Maryland, just to pick Paine up and bring him back. Rather than give the critics more fuel for their fiery attacks on the president, and him, Paine returned instead on a private vessel. Soon, the two wined and dined while the Federalists fumed.

On December 25, Paine sent Jefferson a Christmas card. “I congratulate you on the birthday of the New Sun, now called christmas day; and I make you a present of a thought on Louisiana.” Paine suggested that the United States should purchase Louisiana from Napoleon. He was surprised (and disappointed, thinking his idea was original) to learn by Jefferson’s reply the next day that “measures were already taken in that business.”[4] The quick reply and message were not lost on Paine. It meant that he was, as we would now say, out of the loop.

Spain had ceded Louisiana to France, having taken control of it decades before following negotiations ending the French and Indian War. Recently, the Spanish had closed the port at New Orleans to American traffic, and Jefferson feared the French would soon regain control of New Orleans and continue cutting off American trade on the Mississippi. In that case, in a letter Jefferson sent to Kentucky senator John C. Breckinridge (the senator who introduced the Kentucky Resolutions in Congress, secretly written by Jefferson), Jefferson wrote that the United States would be forced once again to “marry ourselves to the British fleet and nation.”[5] So, the president sent envoys to Paris to try to purchase New Orleans and parts of west Florida (the Gulf Coast) from Napoleon.

The story of what happened next is well known. Envoy Robert R. Livingston was surprised by Napoleon’s response: He offered to sell the entire Louisiana territory to the United States. Napoleon badly needed the money to fund his pending war plans for England. After Napoleon’s failed attempt to put down a slave rebellion in Santo Domingo that cost many French lives, he abandoned his hope of expanding French colonialism in North America and turned his focus once again to Europe. Livingston and James Monroe, who had joined him in Paris, jumped at the deal, exceeding, of course, their authority, not to mention committing U.S. funds vastly in excess of the $2 million that Congress had authorized. The price tag ballooned to $15 million. But that was a bargain the envoys could not refuse. Soon, Jefferson received the wonderful “present” of Louisiana that Paine had mentioned, and the president now had a huge problem: how to get Congress to ratify the agreement and to pay for it.

But Livingston had told Jefferson he had to act with dispatch, lest Napoleon change his mind. Jefferson did, and the Louisiana Territory was purchased. What is less known is Paine’s interest in the business and the efforts he made to support Jefferson’s actions. And from his exchanges with Jefferson, it’s clear Paine put aside his long-held distaste for unbridled executive power and found a constitutional argument to support his old friend’s unprecedented actions.

It was not the first time that Jefferson aggressively exercised executive powers. In the spring of 1801, he sent naval warships without Congressional authorization to the Mediterranean as a show of force to try to stop pirate raids on American merchant shipping by the Barbary states. (Little did he know that Tripoli had already declared war against the United States). American sailors were captured and held for ransom in an effort to force the United States to pay tribute to the North African leaders in order to ensure safe passage for their ships in the Mediterranean. Although Congress was not in session at the moment, it subsequently approved of Jefferson’s action, but without a declaration of war. His action set a precedent for future presidents.

Interestingly, Paine weighed in on that matter, too, in the spring of 1802 before returning to America. He wrote Jefferson from Paris recommending that an American minister be sent to Constantinople, and if the minister was well received “it would be of considerable advantage towards the security of our commerce . . . and [the Barbary states] would, I think, be much checked in their avidity and insolence for war with us if we were on a good standing at Constantinople.”[6] A valuable suggestion for a diplomatic approach. But by then, Jefferson’s military action against the Barbary leaders had already escalated, with secret plots and a larger group of warships.

Back in America, Paine went to work writing letters to encourage Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase. One of the nagging issues for the president was the question of whether he had exceeded constitutional authority to purchase Louisiana. Though he moved forward with the deal anyway, it bothered him, and he expressed that reservation in a letter to Senator Breckinridge. In the letter, Jefferson admitted his action to purchase Louisiana was unconstitutional without Congressional approval, but then he sought to justify it by claiming that it was similar to a guardian protecting his ward for his good, in this case, for the good of the nation.[7]

Paine offered a constitutional argument of a different kind to justify Jefferson’s actions. It was not the first time Paine and Jefferson discussed constitutional issues. As the Marquis de Lafayette reported, “Mr. Jefferson, Common Sense, and myself are debating in a convention of our own as earnestly as if we were to decide upon it.”[8] The three were in Paris at the time and were discussing newly arrived transcripts of the debates over ratifying the Constitution of 1787 in Pennsylvania.

On August 2, 1803, Paine wrote two letters regarding Louisiana, one to Jefferson and the other to Breckinridge, which he sent to Jefferson to pass along to the senator. In both letters he argued that “the instrument of cession is not of the nature of a Treaty.” Paine was reacting to the “federal papers” that were trying to “throw some stumbling block in the way,”[9] and Paine countered their objections to Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase because it necessitated a treaty, by arguing that no treaty applied in this case. In his letter to Senator Breckinridge, Paine had this to say: “Treaties . . . are to have future consequences and whilst they remain, remain always in execution externally as well as internally.” But since the United States would be “the sole power concerned after the cession is accepted and the money paid . . . the cession is not a Treaty in the constitutional meaning of the word.”[10]

It’s doubtful Paine’s clever argument held any weight with either the president or the senator. But he had found a way, in this instance, to craft a constitutional interpretation in support of Jefferson’s unprecedented action, ever mindful that genuine constitutional limitations generally constrained presidential authority.

There is no question that presidential powers have expanded exponentially in the centuries since Jefferson’s presidency. To their credit, founders like Jefferson and Paine cared about the Constitution. And while both struggled to discover arguments to justify the expansion of executive authority in special circumstances, both understood the limitations the Constitution places on the potential abuse of presidential powers.

[1]Thomas Jefferson to Margaret B. Bonneville, April 3, 1813, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-06-02-0044; original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Retirement Series, vol. 6, 11 March to 27 November 1813, ed. J. Jefferson Looney (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), 47.

[2]Jefferson to Thomas Paine, June 19, 1792,”Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-20-02-0076-0014; original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 20, 1 April–4 August 1791, ed. Julian P. Boyd (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), 312–313.

[3]Joseph P. Ellis, American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson(New York: Vintage, 1998), 253.

[4]Paine to Jefferson, December 25, 1802,Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-39-02-0197-0001; original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 39, 13 November 1802–3 March 1803, ed. Barbara B. Oberg (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), 217; Thomas Paine, The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine, 2 vols., ed. Philip S. Foner (New York: Citadel Press, 1969), 2: 1431n.

[5]Jefferson to Robert R. Livingston, April 18, 1802,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-37-02-0220; original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 37, 4 March–30 June 1802, ed. Barbara B. Oberg (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 263–267.

[6]Paine to Jefferson, March 17, 1802,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-37-02-0062; original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 37: 82–84.

[7]Jefferson to John Breckinridge, August 12, 1803,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-41-02-0139; original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 41, 11 July–15 November 1803, ed. Barbara B. Oberg (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), 184–186.

[8]Quoted in David Freeman Hawke, Paine(New York: Harper Colophon, 1974), 185.

[9]Paine to Jefferson from Thomas Paine, August 2, 1803, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-41-02-0102; original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 41: 138–140.

6 Comments

Interesting, informative, and very well-written, Jett! As I recall, Paine got in particular trouble with Robespierre when he called him a hypocrite for advocating for the immediate execution of Louis XVI, since “the Incorruptible” had once argued as a young lawyer against capital punishment in general. Also, your phrase “got lucky” is particularly apt, since I believe that at one point in his confinement Paine avoided a trip to the guillotine when the jailer misapplied a chalk mark to his cell door.

Thanks for your kind words, Rand. I did not know the story about Paine calling Robespierre a hypocrite. Thanks for that! And yes, Paine somehow avoided the guillotine when, according to one version of the story, the door to his cell was open in the evening, because Paine was ill, when the jailer came by marking an X on the doors of those to be sent to the guillotine the next morning, and then closed with the X inside by the time the jailers came by in the morning to escort those with Xs on their doors to their fate.

Very interesting article and enjoyable to read. I did not know that Paine and Jefferson recommenced their friendship and letters after Paine’s return, nor did I know the shared interests they had with the West and Paine’s politicking to secure Louisiana. I do find issue, though, with the objection of Jefferson supposedly acting illegally against the Barbary States. Our shipping was being attacked and our sailors enslaved, and so I would argue that under Article II, the president, as Commander-In-Chief had every right to send ships to DEFEND American shipping, especially since Congress was out of session. This, I would argue, was perfectly constitutional and in align with strict construction. Overall, I very much enjoyed this article!

Thank you very much for your comments and raising your issue about strict construction of Article II: “The President shall be Commander in Chief, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States….” The question, of course, is who has the power to call the military into Service in a conflict abroad. The framers of the Constitution made war making a joint enterprise, by giving Congress the power to declare war and making the president Commander in Chief. Jefferson, in the case of the Barbary pirates, called the military into action in response to an attack upon U.S. ships, while Congress was not in session, and without a declaration of war. The fact that Congress, when it returned, quickly endorsed Jefferson’s action set a precedent. For the next 100 years, presidents would send U.S. troops abroad almost 50 times, without congressional authority. in fact, through Korea, Congress blessed all of these undeclared wars. Then Vietnam (a police power, remember?) came along and Congress decided it was time to rein in presidential war making.

It is not so much the strict language in Article II that authorized the expansion of presidential war making under the Constitution, but all of the precedents over the years, starting with Jefferson, that confirmed the constitutionality of expanded presidential war powers. The Supreme Court has never really settled the constitutional questions re war powers, or whether the War Powers Resolution itself is constitutional.

Great article! So nice to read these “small” unknown items from history. Thomas Paine is a line in most history books, what a fascinating expansion on that basic knowledge! Thanks so much for writing it

Thanks for your comment, Shane. I have a colleague who says of Paine, “that guy is a gold mine.” It has been fun digging into his political thought over the years.