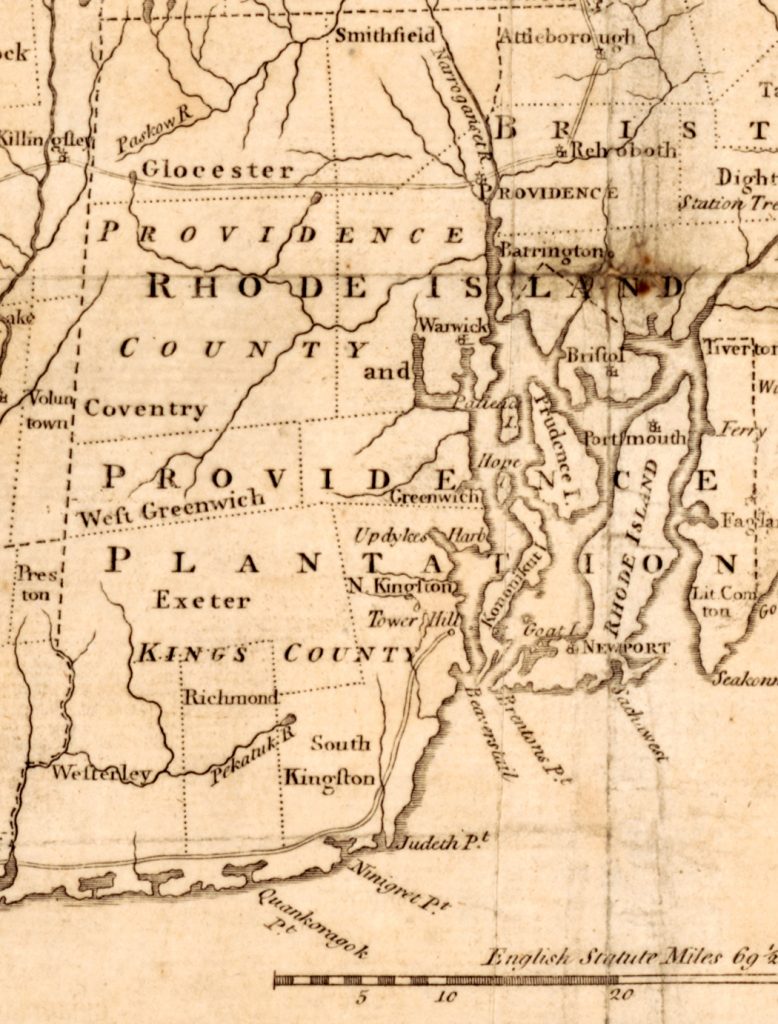

Major General Charles Lee visited Newport, Rhode Island, in late December 1775, where he—controversially—insisted that local Loyalists take an oath of allegiance to the Continental Congress. This approach, and a similar one he took in New York City shortly thereafter, created concern in Congress on how best to handle Loyalists. But by mid-1778, Lee had changed his mind and no longer believed in employing oaths of allegiance.

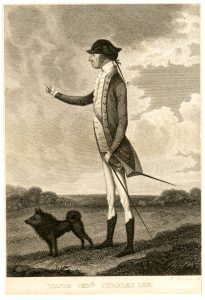

Charles Lee was probably the most remarkable personality of the American Revolution on either side. He was brilliant but eccentric, and well-educated and well-schooled in military matters but had a habit of insulting his superiors. Born in England, he had his first military experience in North America during the French and Indian War. He showed courage by being wounded in a charge. Lee finally received promotion to lieutenant colonel in the British Army. After the French and Indian War ended, he served as a soldier of fortune, serving in high positions in Poland, Russia, and Turkey, gaining valuable experience.

Lee began to make it clear in his letters home that he opposed the system of British monarchy and favored republican government. He decided to move to America in 1773. “Liberty I adore,” he explained, and “where she lives, that is my country.” With his impressive military background, he was immediately hailed as a Patriot leader. He wrote a popular pamphlet arguing that American militiamen could defeat British regulars in battle.

With the coming of war after Lexington and Concord in April 1775, the Continental Congress chose its top generals. As Lee was the best-educated general and had the most military experience, he likely hoped to become the leading general, given that the new Continental Army was so inexperienced. But wanting an American, George Washington was named commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. Lee desperately desired to be second-in-command. John Adams, however, persuaded Congress that since most of the army then outside Boston was from New England, Artemis Ward from Massachusetts should be the second in command. Lee was selected as the third highest ranking general. Lee was outraged. His response was typical—overly harsh but with a kernel of truth. He described the Harvard-educated Ward as “a fat old gentleman who had been a popular church warden, but had no acquaintance whatever with military affairs.” After a few months, Ward, as a result of bad health, retired, leaving Lee as second-in-command.[1]

Lee traveled through Rhode Island via Newport on this trip from Philadelphia to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to assume responsibilities as a major general of the Continental Army still setting siege to Boston. Ezra Stiles, the influential minister of the Second Congregational Church in Newport, wrote of Lee: “General Lee passed through this town to Boston last week. He is an European [i.e., Englishman] but talks high for American liberty, and seems to endeavor to enspirit [inspire] the people to take arms. He says the King is a fool and his ministers rogues and villains.” Stiles, an ardent Patriot, was not yet convinced that Lee was “a sincere Friend to public Liberty.”[2]

Lee commanded a division during the siege of Boston. Two of his brigadier generals were relative novices. One was Nathanael Greene of Coventry and Warwick, Rhode Island, who before the war had helped run a small iron business with his brothers. By war’s end, Greene would develop into perhaps the best field general on either side. The other brigadier general, John Sullivan of Durham, New Hampshire, had been a small-town lawyer prior to the war. In the summer of 1778 he would command American troops during the Rhode Island Campaign, which ended with the Battle of Rhode Island (the battle involving the most troops in New England during the war).[3] Greene and Sullivan honed their craft under Lee’s tutelage.

Newport’s Reverend Stiles was impressed by the fortifications he visited at Cambridge. He praised Lee for being “assiduous in reforming and modeling the Army.”[4]

Back in Rhode Island, from April 1775 through April 1776, Capt. James Wallace of the Royal Navy and his small squadron of British warships terrorized Narragansett Bay. Wallace, commanding from the twenty-gun HMS Rose, was supported by the twenty-gun Glasgow, the sixteen-gun Swan, and a smaller bomb brig. Wallace’s officers and men raided Patriot farms and seized ships, even ones moored in Newport Harbor. He threatened to bombard Newport and Bristol if they did not supply his ships with food and supplies. He did bombard Bristol, causing a former minister then farming in a field to die of heart failure. On December 10, 1775, Wallace raided Conanicut Island, burning some fifteen houses and barns, seizing cattle and sheep, and killing an elderly man. For Reverend Stiles, from Newport, the fires on Jamestown were “an awful sight.”[5] Patriots in Rhode Island tried to fight back against Wallace, but they lacked the naval strength to do so and they became discouraged.

It got worse. In December, intelligence was brought to General Washington that the British in Boston were preparing for an expedition with a large number of troops. It was naturally inferred that this expedition would be taken by sea to capture New York—or Newport, then one of the busiest ports in the thirteen colonies.

Governor Nicholas Cooke of Rhode Island complained in a December 19 letter to Washington that if a British force sailed from Boston to Aquidneck Island, “I tremble for the consequences, as the colony in its present exhausted state cannot without assistance defend the island.” Cooke requested Washington to send a Continental Army regiment to be stationed on Aquidneck Island, and to appoint a general from the Continental Army to take command of the troops there and improve Newport’s defenses. Cooke even mentioned General Lee as a likely candidate.[6]

Washington was sympathetic, but not overly so. He did not want to spare many troops or a general for long. He decided to send Charles Lee to Newport for a quick visit, with orders to provide guidance on how best to fortify Newport’s defenses.[7] Washington also expressed a concern that Newport was “an asylum for [those] who are disaffected to American liberty.”[8] Here, the commander-in-chief was referring to the port’s many Tories, meaning Americans who were still loyal to King George III.

Washington did not send an entire regiment to accompany Lee, as Cooke had requested. Lee traveled to Rhode Island with his personal guard and a small party of Virginia riflemen, perhaps just thirty men in all. Setting out from the American camp at Cambridge on December 20, Lee reached Providence two days later. The Recess Committee of the Rhode Island General Assembly, which handled the day-to-day military affairs of the colony, called up for service “all the Minute-Men in the County of Providence” and appointed Lee to command the troops on Aquidneck Island. Several hundred minutemen in the Providence area answered the call and were joined by a company of young cadets from Providence. Including Rhode Island militiamen already on Aquidneck Island, Lee would command nearly 800 soldiers.[9]

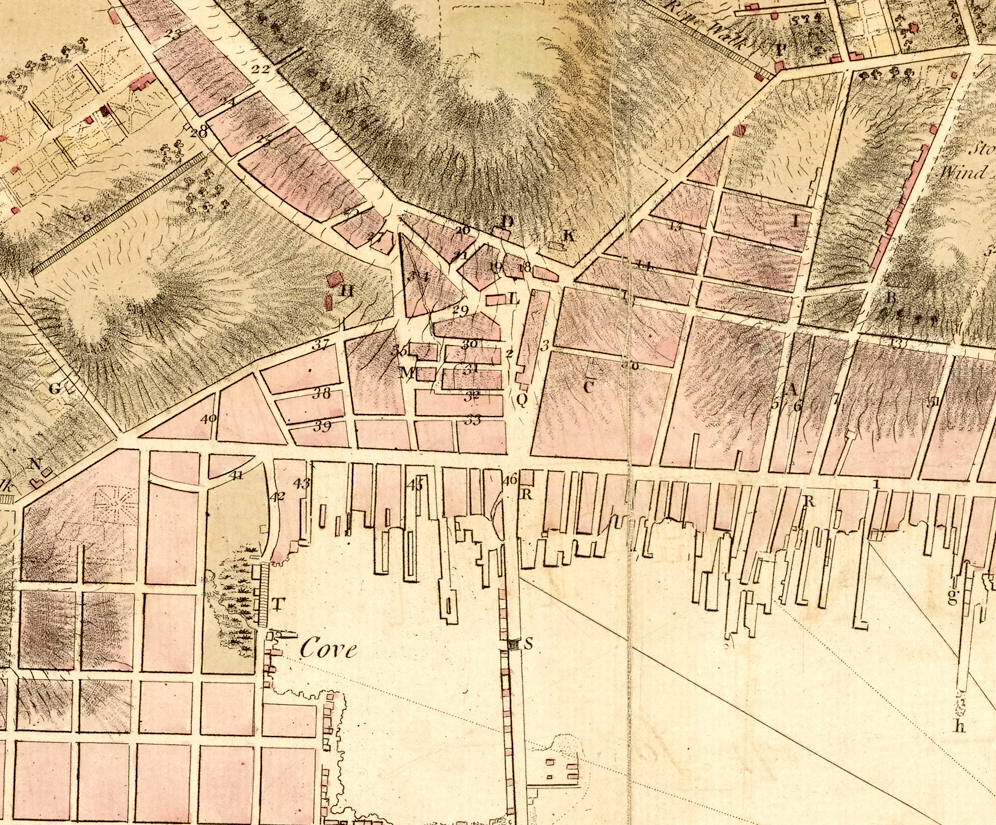

Lee proceeded with his increased escort to Newport, arriving on Christmas Day and remaining there until December 27. In three hectic days, he inspected harbors, made recommendations on fortifications, and intimidated prominent Tories.

When Lee arrived on Christmas Day, he was preceded by his small party from Cambridge and the Cadet Company marching into Newport. According to Ezra Stiles, this was itself a bold act, as Captain Wallace had declared he would fire his ship’s cannon on Newport if any armed Patriot soldiers arrived. Lee stayed at Layton’s “next to the Court House” (the Old Colony House). On the parade grounds in front of the Court House, “Lee declared his advice for all to remove out of town in ten days.”[10] Lee feared Wallace would bombard Newport or that it would be invaded by the brewing expedition from Boston. Lee’s recommendation did not spur an immediate mass exodus; many, especially Patriot supporters, had already left. By the end of the next year, Newport’s population would be half of what it was before the war started.

News of Lee’s arrival alarmed Newport’s Tories. There was a budding civil war about to break out in Rhode Island between Patriots and Tories. Many families on both sides had generations of descendants who had resided in Rhode Island. Patriots had the upper hand in Rhode Island, controlling the colony government and most all of the town governments. (I estimate that at the time war broke out, sixty percent of Rhode Islanders supported the Patriot cause, thirty percent were neutral, and ten percent were Tories. Many of the Tories, however, were prominent men in Newport.)

To the Tories, the Virginia riflemen were intimidating—they were crack shots, carried knives and hatchets, and dressed in frontier garb like the backwoodsmen they were. Charles Lee was intimidating too. He was a radical republican. At this stage of the war, he called Tories traitors.[11] That was a strong word, as the punishment for traitors could be death. Newport “swarms with Tories and suspected persons,” wrote Lee.[12]

Members of Newport’s Town Council, four Tories and three Patriots, met with Lee and offered them all the assistance in their power. “But hypocritically,” wrote Stiles. Town Council members, though they would not admit it publicly, were not particularly impressed by Lee and his show of force. Their numbers were too small to make a difference if a British expeditionary force did invade and it did not appear Lee would stay long. Newporters still had to deal with the threats and demands of Captain Wallace, who showed no indication he would depart soon. Town Council members knew that, to save the town from destruction, they might have to compromise and send provisions to Wallace’s ships.

On the evening of December 25, Lee called and ordered eight prominent Newport Tories brought to him. They were Col. Joseph Wanton, the son of recently deposed Gov. Joseph Wanton of Rhode Island; Rev. George Bissett, the minister of the Anglican Trinity Church; Dr. William Hunter, who commissioned one of Gilbert Stuart’s first paintings (and whose Hunter House is currently open to the public); John Nicoll, the Comptroller of the Customs at Newport; Nicholas Lechmere and Richard Beale, each a Royal customs officer who assisted Nicoll in collecting import duties; and John Bours, a Newport merchant and member of Trinity Church. The Wanton and Bours families had deep roots in Rhode Island extending back to the seventeenth century.

Nathanael Greene later called Colonel Wanton and Dr. Hunter the “principal” Tories.[13] Wanton was particularly under heavy suspicion, as it was rumored, according to Greene, that several of his enslaved African men had served as pilots during Captain Wallace’s raid on Conanicut Island and had “pointed out the houses” of Patriots “to burn.”[14]

Lee demanded that each man take an oath not to give support or intelligence to the King’s troops and to support the Continental Congress. The general did not threaten physical punishment for noncompliance. He did exempt Reverend Bissett as a clergyman and Dr. Hunter as a physician. Nicholl and Bours took the oath and were dismissed.

Three of the Tories—Colonel Wanton, and customs officials Lechmere and Beale—refused to take the oath. Lechmere later recalled the following exchange: “Gen. Lee told him [Lechmere] that he had sent for him because he and his family were very inimical to American liberty.” Lechmere quipped in response that Lee “did him and his family a great deal of honor.” An exasperated Lee allowed Lechmere, Beale and Wanton until the next morning to reconsider. When they did not, he had them arrested and sent to Providence under a guard, where they remained about a week.[15]

A Loyalist taking an oath of allegiance to the Continental Congress, even he did not really mean it as it was done under duress, could still face serious consequences. For example, after the war, many Loyalist claims for compensation of wartime losses filed in London were rejected if the Loyalist had taken an oath of allegiance to Congress.

John Bours had married Hannah Babcock, the daughter of Dr. Joshua Babcock of Westerly, Rhode Island, a firm Patriot and long-time friend of Benjamin Franklin. John and Hannah had eleven children in Newport. But their connections did not prevent Bours from being threatened by Lee. Here is the complete oath signed by Bours:

I, John Bours, here, in the presence of Almighty God, as I hope for ease, honor, and comfort in this world, and happiness in the world to come, most earnestly, devoutly, and religiously swear neither directly nor indirectly to assist the wicked instruments of ministerial tyranny and villainy, commonly called the King’s troops and navy, by furnishing them with provisions or refreshments of any kind, unless authorized by the Continental Congress, or the Legislature as at present established in this particular colony of Rhode Island. I do also swear by the same tremendous and Almighty God that I will neither directly nor indirectly convey any intelligence or give any advice to the aforesaid enemies so described, and pledge myself, if I should, by any accident, get the knowledge of such treason, to inform immediately the Committee of Safety [a Patriot organization]. And, as it is justly allowed, that when the sacred rights and liberties of a nation are invaded, neutrality is not less base and criminal than open and avowed hostility. I do further swear and pledge myself, as I hope for eternal salvation, that I will, whenever called upon by the voice of the Continental Congress, or that of the Legislature of this particular colony, under their authority, take arms and subject myself to military discipline, in defense of the common rights and liberties of America. So help me God.”

Sworn at Newport, Dec. 25, 1776. JOHN BOURS[16]

On December 27, Lee and his soldiers departed Newport. Before leaving, Lee warned that he would send two regiments to Newport to defend it against any threats made by Wallace. (He never did). Wallace, in turn, did not fulfill his promise to bombard Newport if armed men entered the town. Stiles claimed that the British captain drew his ships away from shore, fearing the accurate shots of the “dreaded riflemen.”[17]

Despite the short stay at Newport, Rhode Island Patriots were pleased with Lee’s decisive actions. After his arrival back in Providence on December 28, the Recess Committee presented to Lee a gift in acknowledgement of his services—“one of the best beds with the furniture taken from Charles Dudley,” a Tory.[18] George Washington also heartily praised Lee’s efforts in a letter to Congress. Enclosing with his letter a copy of the oath of allegiance used by Lee, Washington wrote:

General Lee has just returned from his excursion to Rhode Island. He has pointed out the best method the island would admit for its defense. He has endeavored, all in his power, to make friends of those that were our enemies [i.e., Tories]. You have, enclosed, a specimen of his abilities in that way, for your perusal. I am of the opinion that if the same plan was pursued through every province, it would have a very good effect.[19]

The Continental Congress, however, was not yet ready to take such draconian steps with civilian Tories, even if it was recommended by the army’s top two commanders. During the war, Congress never enacted legislation requiring all citizens to take an oath of allegiance.

In 1846, the first U.S. college history professor, Jared Sparks of Harvard College, wrote of Lee’s requiring Tories to take oaths: “The policy of such an oath, administered under such circumstances, may perhaps be questioned. It might deter offenders through fear of detection, but it could scarcely weigh upon the conscience, or soften the will.”[20]

Lee must have heard the grumblings in Congress and he became defensive. In a January 22 letter, Lee tried to explain his actions in Newport to Congress, employing his typically colorful language:

The plan of explaining to these deluded people [Tories] the justice and merits of the American cause, is, certainly generous and humane, but I am afraid will be fruitless. They [Tories] are so riveted in their opinions, that I am persuaded should an angel descend from heaven, with his golden trumpet, and ring in their ears that their conduct was criminal, he would be disregarded. I had lately myself an instance of their infatuation, which if it is not impertinent, I will relate.

At Newport, I took the liberty, without any authority, but the conviction of the necessity, to administer a very strong oath to some of the leading Tories, for which liberty I humbly ask pardon of Congress. One article of this oath was, to take up arms in defense of their country, if called upon by the voice of Congress. To this, Colonel Wanton, and others flatly refused their assent. To take arms against their sovereign, they said, was too monstrous an impiety. I asked them if they had lived at the time of the [English] Revolution, whether they would have been revolutionists [i.e., supporters of Oliver Cromwell and his Puritan dissenters versus Royal forces]? Their answers were at first, evasive, circuitous, and unintelligible; but by fixing them down precisely to the questions, I, at length drew from them a positive confession, that no violence, no provocation on the part of the Court [Lee], could prevail upon them to act [against Great Britain]. Such I am afraid is the creed and principles of the whole party, great and small; sense, reason, argument, and eloquence, have been expended in vain, and in vain you may still argue and reason ’till the end of time.[21]

The peace that Lee had imposed in Newport was short-lived. Wallace’s raids from Narragansett Bay continued. On January 12, 1776, he landed some 250 men on Prudence Island who burned seven dwellings and carried off a hundred sheep. The next day, Rhode Island militiamen departing from Warren and Bristol landed on the island and skirmished with the British, resulting in casualties on both sides.[22] Still, Wallace kept command of Narragansett Bay and the Newport town council would soon petition the Continental Congress to allow it to agree to Wallace’s demands to furnish water and provisions for his ships in return for the safety of their city.[23]

After visiting Rhode Island and returning to Cambridge for a short stay, on January 8, 1776, Washington sent Lee to New York City to strengthen its defenses against an expected invasion there—and to intimidate Tories. Lee promised Congress that he would purge “all its environs of traitors.” He again administered oaths to prominent civilian Tories.[24] After Lee sent a radical Patriot, Isaac Sears, to Queens County, the general must have smiled when reading Sears’s report. “I . . . tendered the oath to four of the great Tories, which they swallowed as hard as if it was a four pound shot that they were trying to get down,” Sears wrote.[25]

In June 1776, the Rhode Island General Assembly passed an act that became known as the Test Act. It empowered any member of the General Assembly who suspected a neighbor of being unfriendly to the Patriot cause to summon the neighbor before him and demand he should subscribe to a loyalty oath. Among the first persons arrested under the Test Act were John Nicoll, Richard Beale, and Nicholas Lechmere. For refusing to take the loyalty oath, they were exiled to rural Gloucester for about eleven weeks.[26]

In December 1776, Charles Lee was captured at a tavern in Basking Ridge, New Jersey, three miles from the main body of his troops, by a party of British dragoons. Within a few months of being confined to two rooms in British-held New York City, Lee had a startling change of mindset. As I explain in my recent book, Washington’s Nemesis, he no longer thought the Americans could win the war. He lost confidence in George Washington to lead the Continental Army to victory. To save bloodshed on both sides, he drafted and submitted to British commanders a plan on how to defeat the Americans quickly and force them to renounce their Declaration of Independence. I argue that this shocking action constituted rank treason. But because it remained secret for seventy-five years, the Americans never discovered it and Lee was able to return to the Continental Army as its second-in-command.[27]

Lee’s dramatic change of mindset was also reflected in how he viewed oaths of allegiance after his return to the Continental Army. In May 1778, he was required by Congress to take the oath of allegiance to Congress, as were all Continental Army generals. Washington administered the oath. During the oath, Lee kept removing and then replacing his hand on the Bible. Finally, Washington stopped the ceremony and asked Lee to explain himself. Lee responded, “As to King George, I am ready to absolve myself from all allegiance to him, but I have some scruples about the Prince of Wales.”[28] After the laughter by onlookers subsided, Lee proceeded to finish the oath. Most historians make light of the episode, but considering Lee’s change of mindset the affair takes on new meaning.

Later, in 1779, Lee condemned a Virginia loyalty oath to Congress as “horrid and insane” on the ground that America might wish to rejoin the British empire under a “just and amicable prince” (such as the Prince of Wales, presumably).[29] Of course, this viewpoint was counter to his own prior practice of ruthlessly insisting that prominent Tories take loyalty oaths to support Congress at Newport and New York City.

[1]For this background on Lee, see Christian McBurney, George Washington’s Nemesis: The Outrageous Treason and Unfair Court Martial of Major General Charles Lee during the Revolutionary War (Savas Beatie, 2020), 32-40.

[2]Franklin B. Dexter, ed., Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles, 2 vols. (New York, NY: Charles Slocum Co., 1901), 1: 453-54.

[3]See Christian McBurney, The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Joint Operation of the Revolutionary War (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2014), chapters 3-9.

[4]Dexter, Literary Diary, 1: 585.

[6]Nicholas Cooke to George Washington, December 19, 1775, in W. W. Abbot, ed., The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 1987), 2: 581.

[7]Nathanael Greene to Samuel Ward, Sr., December 18, 1775, in Richard Showman, ed., The Papers of General Nathanael Greene (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina, 1976), 1: 165.

[8]Washington to John Hancock, December 25, 1775, in Abbott, ed., Washington Papers, 2: 602.

[9]Providence Gazette, December 30, 1775; Newport Mercury, December 25, 1775 and January 1, 1775; Minutes of the Recess Committee, December 22, 1775, in John K. Robertson, ed., Proceedings of the “Recess” Committee of the Rhode-Island General Assembly 1775-1776 and the Rhode-Island Council of War 1776-1782 (East Providence, RI: Rhode Island Publications Society, 2020), 16.

[10]Dexter, Literary Diary, 1: 645.

[11]Charles Lee to John Page, April 16, 1776, in “The Lee Papers, 1754-1811,” in Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the Years 1871-1874, 4 vols. (New-York Historical Society, 1872-75) (“Lee Papers”), 1: 427; Lee to Daniel of St. Thomas Jenifer, May 6, 1776, in ibid., 1: 473-74.

[12]Lee to Robert Morris, January 3, 1776, in ibid., 1: 233.

[13]Greene to Ward, Sr., December 31, 1775, in Showman, ed., Greene Papers, 1: 174.

[14]Greene to Ward, Sr., December 18, 1775, in ibid., 1: 165.

[15]Dexter, ed., Literary Diary, 1: 645-46; Providence Gazette, December 30, 1775; Memorial of Nicholas Lechmere, in Hugh E. Egerton, ed., The Royal Commission on the Losses and Service of American Loyalists, 1783 to 1785 (New York: Burt Franklin, 1915), 236-37.

[16]Quoted in Samuel G. Arnold, History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, 2 vols. (Providence, RI: Preston & Rounds, 1899), 2: 365-66n1. Slight spelling and punctuation corrections have been made.

[17]Dexter, ed., Literary Diary, 1: 646.

[18]Lee to Nicholas Cooke, January 9, 1776, in Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, New Series, vol. 36 (1926), 300-01; Minutes of the Recess Committee, December 28, 1775, in Robertson, ed., Proceedings of the “Recess” Committee, 17.

[19]Washington to Continental Congress, December 31, 1775, in Abbott, ed., Washington Papers, 2: 624.

[20]Jared Sparks, “Life of Charles Lee,” in Lee Papers, 4: 258.

[21]Lee to President of Congress, January 22, 1776, in ibid., 1: 248.

[22]See Arnold, History of Rhode Island, 2: 366; Robert Grandchamp, “Rhode Island Militia Battles the Dreaded British Captain James Wallace on Prudence Island,” in the Online Review of Rhode Island history, smallstatebighistory.com/rhode-island-militia-battles-dreaded-british-captain-james-wallace-prudence-island/.

[23]See Cooke to Lee, January 21, 1776, in John R. Bartlett, ed., Records of the Colony of Rhode Island. (Providence, RI: A. Crawford Greene, 1862), 7: 449; see also Washington to Cooke, January 6, 1776, in ibid., 7: 446-47.

[24]See Lee to President of Congress, March 5, 1776, in Lee Papers, 1: 348; Lee to Isaac Sears, March 5, 1776, in ibid., 1: 346.

[25]Sears to Lee, March 17, 1776, in ibid., 1: 359.

[26]See Resolutions, June 1776, in Bartlett, Records of the Colony of Rhode Island, 7: 566-70 (Nicoll, Beale and Lechmere were joined by Tories Thomas Vernon and Walter Chaloner); Memorial of Nicholas Lechmere, in Egerton, ed., The Royal Commission on the Losses and Service of American Loyalists, 237.

[27]See McBurney, George Washington’s Nemesis, chapters 1 through 5. The second half of the book addresses Lee’s command at the battle of Monmouth Court House on June 28, 1778, and his subsequent court-martial and conviction for failing to attack the enemy pursuant to orders and for an unwarranted retreat. For more on Lee’s capture, imprisonment and exchange, see Christian McBurney, Kidnapping the Enemy: The Special Operations to Capture Major Generals Charles Lee & Richard Prescott (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2014), passim.

[28]John R. Alden, General Charles Lee, Traitor or Patriot? (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1951), 202 and 340n17.

[29]Lee to Captain Hunter, undated (some time in 1779), in Lee Papers, vol. 4, 45.

3 Comments

Explains very clearly Lee’s “change of heart” over imposing loyalty oaths upon the Loyalists. He remains a fascinating character in the Revolution. We’ll probably never know how he could make so many twists and turns.

Great article thank you

Very informative article from which I intend to quote. But I need a more exact citation for the quote “lost confidence in George Washington.. able to return to the Continental Army as its second-in-command.”

Also, I am sore disappointed that the image of Gen. Charles Lee that was used is not the one by Samuel Blyth. O well..