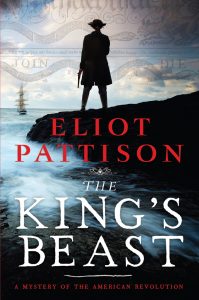

Author Eliot Pattison’s new book is The King’s Beast: A Mystery of the American Revolution (Counterpoint, 2020), sixth in his Bone Rattler series set in Revolutionary America. We asked the author about his historical novel and the research behind it.

Author Eliot Pattison’s new book is The King’s Beast: A Mystery of the American Revolution (Counterpoint, 2020), sixth in his Bone Rattler series set in Revolutionary America. We asked the author about his historical novel and the research behind it.

The entire Bone Rattler Series takes place around the era of the American Revolution. What drives your interest in this time period?

From the long view of centuries, this was one of the most extraordinary periods in all of Western history. The years after the French and Indian War witnessed an explosion of scientific and geographic discovery, literacy, economic independence, and speech in the public forum. Over the course of these years in the middle of the century the self-identity of immigrants began shifting from that of British colonists to that of Americans. This remarkable process, which in retrospect can be seen as the bedrock of the Revolution, lies at the heart of my series. Years after the armed struggle that culminated in independence, John Adams observed that “the Revolution was effected before the war commenced. The Revolution was in the hearts and minds of the people.” This struggle in the hearts and minds of a population which had been conditioned to the suffocating, semi-feudal constraints of British society has always fascinated me, and is intertwined with the transformative developments underway in society generally. My novels bear witness to the pain and exhilaration of this process. I think every serious student of the nation’s birth has to start with this struggle, and with thesecritical years before the first shots were fired on Lexington Green.

The protagonist of The King’s Beast is a transported Scotsman named Duncan McCallum, but also integral to the story are Native Americans of differing tribes, Africans, and women. It’s clear that the America inhabited by these characters is a richly multicultural landscape. Can you discuss your decision to develop a diverse cast of characters in your portrayal of eighteenth century America?

At the outset of this series I committed to make my presentation of eighteenth century society as authentic as possible. This is a duty that historical novelists owe to readers. I also believe that when well done, historical novels have the power to engage readers with the past much more intimately than any classroom text. Our history books focus us on the more prominent Founding Fathers, who were a relatively homogenous group. Somehow our text writers seem to have forgotten that half of the people living in America were female, a significant percentage were of African origin, and Native Americans, while fading, still exerted a profound effect on the frontier where important elements of the American character were being forged. As reflected in The King’s Beast, women played a very important role in the non-importation movement, and matriarchs were often the most influential members of the tribes. I can’t imagine telling these stories without such characters –it would not only be disingenuous but also a disservice to these groups and our history.

There were also many diverse ethnicities, including Scotch, Irish, Welsh, Cornish, Palatine German, Flemish, and French, as well as different native tribes and religions, all of which had many more distinct characteristics than our history books typically ascribe to them. Diversity is a vital part of the American story and that dynamic should not be seen simply in gender or ethnic terms. The early colonies were in many ways founded and populated by a dazzling range of what we would call identities today. The country was only made possible by bridging those differences with a common cause. The story of how these disparate threads joined to make the unique tapestry of America is in many ways the story of the nation’s birth. E pluribus unum was then, and still is, essential to the American identity.

The King’s Beast centers around half-buried bones found in an area of Kentucky called the Bone Lick or God’s Gate, an evocative, mysterious place of sulfur springs and salt licks. Half-buried in this land were the fossilized bones of colossal beasts that once roamed America—the incognitum. In your novel, as in real life, these bones caught the attention of Benjamin Franklin. What drew you to such an interesting—and not widely known—subject?

In each book of this series—The King’s Beast is the sixth installment—I deliberately incorporate elements of the period that I believe have been understated or even overlooked in our history texts, and try to present them in a way that will entice my readers to keep turning pages. In prior books these have included the role of Moravian missionaries, Native American and Scottish slaves on tobacco plantations, the amazing colonial rangers, the struggles of American Jews, the dying tribes, and even the colonial fascination with electrical apparatus. A fundamental element throughout my series is the remarkable bond—verified in the chronicles—that evolved between the Highland Scots and the woodland tribes, which is poignantly reflected in the opening scenes at the Bone Lick.

Early efforts at what we would today call paleontology have always intrigued me, and I very much wanted to explore these with a fictional palette. The bones of the incognitum raised many provoking questions. How, for example, did the native tribes react when they encountered these remains of creatures they could not identify? With fear? With spiritual awe? My presentation of the Bone Lick and the excitement its fossils stirred is entirely authentic. Wild speculation about what these creatures might have been spread across the Atlantic and the debates about their derivation reflected many of the dynamics that defined European society. The aristocracy largely considered scientific advancement to be the province of kings and scoffed at the notion of commoners engaging in such pursuits. Tempers flared in the religious establishment over suggestions that one of God’s creatures could have gone extinct or that the bones belonged to a race of giant men exterminated in holy wrath. The bones took on a uniquely American character— defiant of convention and troubling to European sensibilities. Franklin’s energetic curiosity drove him to ask for samples to be shipped to London, and we know that the Irish frontiersman George Croghan shipped several to Franklin’s London home. A generation later Thomas Jefferson dispatched Lewis and Clark separately to retrieve bones, which he eventually scattered across the White House floor for his personal study. The mystery of these American bones coincided so perfectly with the mystery of the evolving American identity that it seemed the perfect centerpiece for a novel.

How did you approach the research process for The King’s Beast ? Was it any more difficult, or easier, than research on other time periods or events that you’ve worked with?

My research always starts with reading chronicles of the time—newspapers and journals—which provide wonderful atmospherics for my novels. Then I move to biographies of the historical figures I will feature, which in this case meant I paid a lot of attention to Benjamin Franklin, especially during his many years in London. There are wonderfully fertile sources that capture the rhythms of eighteenth century life, which are of great help in adding period texture to my books. Throughout this series, though, I have been frustrated by the scarcity of direct chronicles of the interactions on the frontier between Europeans and the native tribes. The actors on this stage were not devoting a lot of time to keeping diaries, and we have very few records of what transpired at Iroquois council fires.

I was so engrossed in research for The King’s Beast that the biggest challenge became when to disengage and lift the novelist’s pen. To build an authentic, and engaging, story, I found myself researching such diverse topics as the street life of mid- eighteenth century London, the Sons of Liberty, the sailing ships of the period, 250 year old street maps of London and Philadelphia, the economy of early Pittsburgh, the Royal Kew Observatory, eighteenth century astronomy, the Mason Dixon Line and Bedlam hospital—all of which play roles in my novel.

Did anything surprise you in the course of researching the fossilized bones or Franklin’s interest in them?

I cherish the unexpected twists that always arise along the path of studying this period. My biggest surprise in researching the themes and backdrops of The King’s Beast related to the efforts of the British establishment to suppress the advancement of natural philosophy—what we would call scientific pursuits—in the colonies. Beyond the controversy over the artifacts of the Bone Lick I discovered the remarkable drama over the transit of Venus of 1769, which engendered fierce rivalries and political turbulence that touched even the scholarly Charles Mason of Mason-Dixon fame. I was happily surprised to learn that the first “scientific” calculation of the distance from the earth to the sun, made possible by the transit of Venus, was actually conducted by what London called amateurs in Philadelphia. This development added fuel to the king’s smoldering resentment of the colonists.

I was also pleased to discover that the first recorded characterization of a fossil in America was made earlier in the eighteenth century, by a slave on a Carolina plantation who recognized the features of elephants from his native land. Another unexpected fact that I uncovered in researching Franklin’s troubled campaign for the adoption of lightning rods was that in this very year, 1769, a lightning strike near Venice hit an arsenal and killed three thousand people. I was able to reflect both of these points in my novel. I also touch upon another unexpected fact, that steam power was not a product of the nineteenth century, as I think many believe—James Watt received his first steam engine patent in this eventful year of 1769.

How does your training as an attorney inform your historical fiction? Has your legal training prepared you in any significant way for your research or writing processes?

A good lawyer has to be adept at both the spoken and written word, and also should be an astute observer of motives and perspectives. These are skills that translate well into the world of the novelist. I also have no doubt that my legal research training has strengthened the extensive research I conduct for each of my novels.

What can we expect from you next? Are there any other works in the pipeline?

In the next book in this series I will take readers on a journey with Duncan McCallum into 1770, the tumultuous year of the Boston Massacre. That struggle for hearts and minds that I mentioned earlier grows much more intense during the opening of this decade. As he forges an ever closer tie with the Sons of Liberty, Duncan will be swept up in unexpected and dangerous ways by the rising wave of American freedom.

PURCHASE THE KING’S BEAST FROM AMAZON IN PAPER OR KINDLE

(As an Amazon Associate, JAR earns from qualifying purchases. This helps toward providing our content free of charge.)

One thought on “An Interview with Eliot Pattison, Author of the Bone Rattler Series”

Recognition of the tremendous diversity of America at the dawn of the Revolution is key to understanding why different ethnic groups responded in different ways to the RevWar. Author Eliot Pattison is on the right track!