Typically, countries at war do not detain enemy prisoners in the backyards of their citizens. During the Revolutionary War Britain’s soon-to-be independent North American colonies proved an exception to this rule. For the fledgling nation, the action was a matter of necessity, one which forced host towns across the colonies to confront the fight for American nationhood in a most unusual way.

Independence from Great Britain was hard won, and with every victory came the challenge of detaining more prisoners of war. The Continental Congress housed most of these men, and in some cases their wives and children, in rural towns throughout the colonies. One such town was Rutland, Massachusetts. After the American victory at Saratoga, the Continental Army pried Rutland’s doors open to host prisoners of war. For the remainder of the conflict, the local town meeting and the Continental Army struggled over the issue of legitimate authority. The imposition pitted New Englanders’ persistent reverence for local government against the authority of the national government which the Revolution sought to establish.

Similar to many other New England towns, Rutland was locally governed from its earliest years. In 1715, the proprietors of the land that would become the town appointed men to the “Committee of Rutland” to “see that justice and equity was done to the settlers.”[1] The committee ensured the town’s prosperity by permitting the settlement of established and hard-working families. The enforcement of this informal regulation indicates a subtle characteristic of the town that would grow more prominent over time: centralized local authority. Even before there was an official town meeting in Rutland, a single group of landowners possessed authority over those who lived there. In 1722, the Great and General Court of Massachusetts incorporated Rutland and empowered its leading citizens to establish a town meeting.[2]

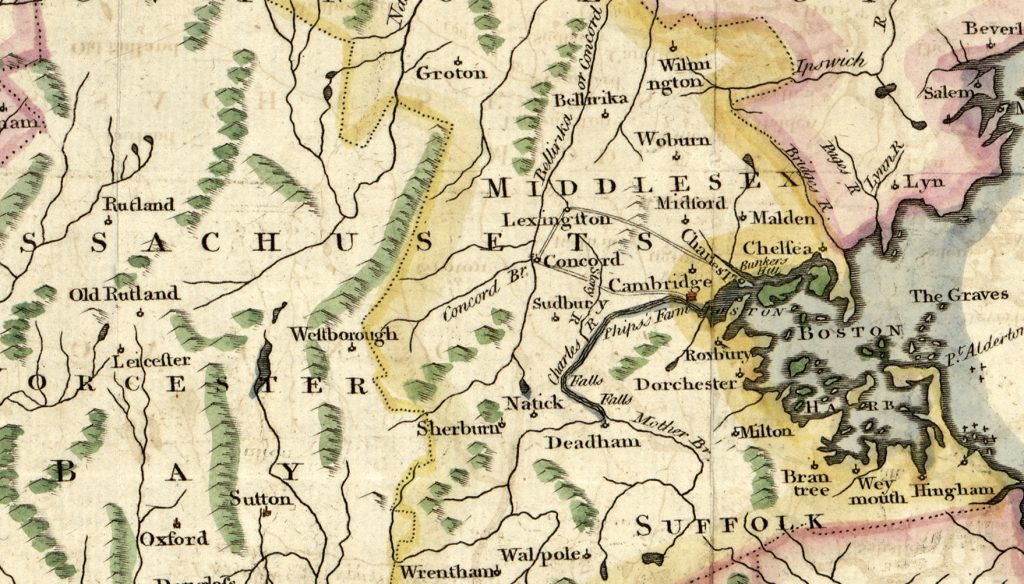

In the years leading up to the Revolutionary War, Rutland sided with the Patriot cause. In 1773, the town meeting received a copy of the Boston Pamphlet from the city’s Committee of Correspondence, which asked it and other meetings in the colony whether they would “stand firm as one Man to recover and support” their colonial rights lately infringed upon by the British Parliament.[3] The Rutland town meeting recognized the committee’s list of grievances as “agreeable to truth & justice” and vowed “not only in the present but in all future occurrences of this kind we shall be ready to joyn with you and others . . . By all Lawful Endeavours in the preservation and Defense of our Charter Rights & privileges.”[4] A year later, the passage of the Massachusetts Government Act of 1774 solidified Rutland’s Patriot alignment. The act essentially dissolved the Massachusetts legislature, and abolished the legality of town meeting. In response, outraged Rutlanders and other local Patriots mobbed the home of John Murray, Rutland’s representative to the General Court, for his support of the act.[5] When war broke out on April 18, 1775 at the skirmishes of Lexington and Concord, Rutland sent militiamen to fight and also allocated town funding for the care of the soldiers’ wives.

In 1777, the American victory at Saratoga resulted in the capture of nearly 6,000 men.[6] The surrender agreement was called the Convention of Saratoga, so the captives came to be called the Convention Army. The captive Convention Army first marched to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to await the result of ongoing negotiations in Congress over their status. When discussions with the British to exchange the enlisted men under the terms of the ill-conceived Convention ultimately soured, Congress appointed Gen. William Heath to find indefinite accommodations for the Convention Army. Since the beginning of the conflict, Congress had favored a humane style of prisoner hosting. As such, it called for enlisted men to be confined in barracks rather than prisons, and also allowed officers to serve their detention in residences, churches, taverns, and other private buildings. Ken Miller argues that the two main reasons for this generous style of prisoner management were the “faint tug of kinship borne of a sense of common identity” with the British and the promise that “humanitarian policy could legitimize, even sanctify, the American rebellion, while potentially alleviating the distress of rebel prisoners.”[7] Congress’s prisoner management policies, however, were poorly enforced and frequently made untenable by unforeseen circumstances and an ever-increasing number of prisoners. These shortcomings intensified local contentions for authority between the army and town meetings.

In December 1777, Heath selected the patriotic, rural town of Rutland to serve as host for the Convention prisoners of war. He sent army officials from Cambridge, including John Gooch, who was to be the Quartermaster of the Rutland barracks, to make preparations for the relocation of the Convention Army prisoners.[8] Gooch met resistance from townspeople almost immediately against housing the officers in their homes. In response, the Massachusetts General Court ruled,

there being no rooms to be procured in Rutland aforesaid suitable for quartering the officers of the Convention . . . the Committee of Correspondence &c in the Town of Rutland be . . . hereby are directed to deliver to Major General Heath . . . the dwelling house lately owned & occupied by John Murray . . . for the purpose of quartering such of the officers of the Convention as he shall think proper.[9]

Thus the home of Rutland’s most hated Tory, John Murray, the ousted colonial representative, became a home for other hated Tories, captive British and German officers. By mobbing the Murray family out of town, Rutlanders had helped the Continental Army and its captive charges, their new pests, to move in.

After Gooch secured lease of the Murray house for the quartering of the British officers, town meeting members defied his authority to seize it. One day upon his arrival at the house, he discovered that the doors were nailed shut. Gooch related to General Heath that, after taking the nails out, he was met with the angry tenant of the home. The man “arm’d himself with sword & musket & indeed with a most terrifick Figure & swore if I did not imediatly quit the Room he would dispatch me.” After a short standoff, the tenant calmed himself enough to retreat. When he returned a short while later, Gooch reported to General Heath that he brought reinforcements in the form of “15 to 18 politicians whome I afterward found were under the Directions of Deacon How & Major Clap,” leading members of the town meeting. Gooch related to Heath that the men then “demanded of me by what Powers I acted,” and after presenting them with the documentation of his lease, they “concluded I had no Power to take Possession till the first of May.” The town meeting had relented, but only by contractual obligation. Gooch ended his letter to Heath by saying that he hoped his letter would “place in a proper Light the disagreeable situation [he was] in between the Civil and the Military.”[10]

Gooch continued to face the hostility of the town meeting while overseeing the barracks construction for the enlisted men. As he began procuring building materials for the task, the town meeting invited Gooch to a special session to discuss the impending prisoners. At the meeting, he again encountered the resistance of the committeemen against his purposes:

Instead of affording me the assistance I required, [the town meeting] had been making all the interest in their power to prevent the officers being quartered, & the first step taken was to put to vote wether they would admit the officers into the Town . . . a large majority was for not admitting them on any terms[.] I informed them that by the Convention [the prisoners] were to be quartered and that my orders were to procure quarters, & that I looked on the vote they had then passed as of no consequence, & should pay no regard to it, & that it was not in their power to support it, unless they voted themselves superior to the Legislative Body to which they were or ought to be subordinate . . . [I am] subject to a set of men chosen into office from no other recommendation than that of being irrationally noisy.[11]

Gooch considered himself, as member of the army of the colonies together, to have the authority to relocate the Convention prisoners to Rutland. The town meeting, as the sole local government of Rutland since its founding, saw it as their right to refuse the entry of the prisoners. It did not recognize the authority of the Continental Army as superior to their own on what they perceived to be a local issue. Gooch was facing down a situation of contested authority, one which would persist throughout the rest of the war.

Construction began on the barracks despite the town meeting, but Rutlanders slowed its progress by price-hiking and incessant complaining. Joshua Mersereau, the Deputy Commissary General of Prisoners for the Continental Army, was constantly distracted by complaints, writing, “The inhabitants, selectmen, etc. waited on me twice to know whether [the officers] were permitted to go about the town on Sabbath days, some saying if they came therein, they would shoot them.”[12] Meanwhile, purchasing materials for the barracks was nearly impossible due to high prices. In early fall, Gooch wrote to Heath of the local sellers saying, “There is no bounds to their avarice. They even take pains to send all round the Country to raise the Price of all such articles as they think we shall stand in need of . . . they are so very greedy here. They are like a set of Sharks watching for every advantage . . . I often when amoungst them fancy myself surrounded by a set of Hungry Devil[s].”[13] Another officer concurred, writing, “everything hath risen fifty percent since the news of the troops being ordered here. The people are all fearful lest they should get less than their neighbors—avarice and extortion in its full corner.”[14] Some Rutlanders, regardless of their loyalty relating to the ongoing authority contest between the Continental Army and the town meeting, were seizing the opportunity to make money out of the prisoner situation.

The Massachusetts colonial government was often forced to intervene where the town meeting did not on issues related to housing the Rutland prisoners. A few weeks before the enlisted Conventioneers were set to arrive, Gooch’s patience with the local government was wearing thin. He wrote to General Heath lamenting his being “plagued with committeemen,” and insisted he was “at present in such a situation as I should by no means have to be in, subject to the insult of every committeeman . . . [I] beg your honor will direct me what to do.”[15] These intrusions made clear to Heath that town meeting was unwilling to control the avarice and pestering of its members and constituents. With little other choice, he defaulted again to the Massachusetts General Court for their intervention. In response to the issue of procuring brick for the barracks, the Court passed a resolution that read, “there are a number of Bricks in the hands of several persons living near said Town of Rutland, who are unwilling to dispose of the same, whereby the finishing of said Barracks is totally prevented and the Interest of the Continent greatly injured,” and that therefore, the builders were empowered to “seze and take into their custoday said Bricks.”[16] By overlooking and participating in opposition to the army, the town meeting was relinquishing local control to the colonial government.

Prisoners of war began arriving in Rutland in late summer 1778. Conventioneers, as well as infantrymen from the 71st Regiment of Foot, captured in Boston Harbor in 1776, brought domestic challenges in tow.[17] In July Col. Joshua Davis wrote to Heath complaining that the 71st Regiment prisoners “ar not so Sivel [civil] as I could wish, a few Days past have bin fighting in ye Evenings & insulting the inhabitants, abusing Som of our [people].”[18] Mersereau also wrote of incessant inquiries by inhabitants and committeemen of the rules to which the prisoners were beholden, reflecting the insecurity of those rules in practice. After the Conventioneers arrived, commanding officer Capt. William Tucker was forced to intervene in a fight that broke out between three captive officers and the overseer of the Murray estate farm, William Henry. Tucker relayed to General Heath that many townspeople had collected to witness the event, and were “very uneasy” over the situation.[19]

Opportunistic inhabitants were eager to exploit prisoner labor, hindering the ability of officials to keep them confined and further straining relations between the army and the meeting. Upon his eventual escape from captivity, George Holmes of the 53rd Regiment of Foot reported to the British Army that he “worked in different parts of the Country at his trade a Shoemaker” during his time in Rutland.[20] Holmes was not the only one to enjoy such freedoms. Responding to the order not to allow the prisoners out of the barracks except to collect provisions, on July 24, 1778 Lt. Col. Nathan Tyler wrote to Heath, “I inform your Hon’r that there are (as I am informed) a number of the Convention troops by some means at work for the inhabitants of this and neighboring towns . . . I find the Inhabitants are not only Desirous of keeping them, as labour is very scarce, but urgent for me to let out more.”[21] Heath responded by insisting, “I have only to repeat that it is my Express order that they don’t [leave the barracks for work] as it is productive of many ill consequences too obvious to need mentioning.”[22] On the same day, Heath took a rare occasion to send a letter to the Rutland town meeting requesting their compliance as the Convention prisoners continued to arrive. “The having these Gentry so near you will undoubtedly create you much trouble & difficulty,” he wrote, “But you will please to remember Gent. that they must be some where . . . I am to desire that you would give all the aid assistance in your Power to the officer acting in the Quarter Master Generals department in the procurement of Quarters for the officers from Time to Time.”[23] Heath received a lukewarm response from the meeting:

Were it in our Power Sir, we should with the utmost cheerfulness afford every beneficial assistance in that way; But your Honr will please to consider, that Dwelling Houses in this & the Neighboring Towns, are in general, fitted rather for necessary Family Conveniences . . . [and] it seems the Proprietors of [the unutilized homes] are Determined and that upon principal, not to admit of any of those officers taking up Quarters with them, on any Terms, whatever; for which Determination Sir, we do not pretend to censure them.

The meeting took the further liberty to inform General Heath of the “other Difficulties” of hosting the prisoners, namely the public drunkenness of the officers and coming and going from the town at their leisure.[24] The town meeting’s lack of enthusiasm over supporting the army’s local endeavors perhaps further discouraged Heath from directly dealing with them about the prisoners. The correspondence would prove the only one between Heath and the Rutland town meeting during the war.

The persistence of forgery and misbehavior amongst the prisoners suggests that the town meeting’s opposition to their management was not unfounded. In July 1778, Tyler wrote General Heath asking, “the prisoners of war, stationed in, or stroling about the Town, who are mischevious and troublesome, whether to secure them . . . within the stockade or not.”[25] Officials reported such misbehavior to Heath with striking regularity throughout the Convention Army’s stay. The issue of forgery also highlighted the inconsistency of prisoner management policies in Rutland. In the same letter Tyler continued, “I finde a number of old passes in the possession of the Convention Troops . . . which were one to judge mearly by their complexion, must suppose they survived the Deluge[.] They appear to have suffered many alterations.”[26] The Conventioneers were presenting old parole passes from their previous locations of confinement, attempting to game the weakly-established system of confinement in Rutland. The prisoners were not eager to adhere themselves to the rules of confinement, and lacking sufficient guards and provisions to feed the men, the officials in Rutland were ill-equipped to force them into submission.

The perception of disorganization in the ranks of the Continental Army eventually turned the complaints of the town meeting into formal investigations of mismanagement. Following a slew of successful prisoner escapes, at the end of summer 1778, the meeting accused Joshua Mersereau of accepting payment in exchange for allowing prisoners to escape. Mersereau attempted to apprehend three men who escaped “from the barracks of the 71st Regiment” by advertising in the Massachusetts Spy. He offered a ten dollar reward per man for the return of Alexander Adamson, James Dowell, and James Moat, the latter of whom “had on when he went away, a red coat faced with blue, with the 21 on the buttons.”[27] Despite this attempt however, Mersereau still stood trial. The deputy denied the accusation of paid escapes in a letter to General Washington dated August 31, 1778, saying, “I am confident that there is not an officer of the Convention, [who] can say that they have given me one Single Farthing.”[28] However, his plea to Washington was insufficient to stop the investigation. Rutlanders brought their charges to the Massachusetts General Court, which then led an investigation into Mersereau’s recent behavior. During the trial, Mersereau was formally cleared of charges.[29] However, his legal clearance did not clear him in the eyes of his hosts, and he remained under suspicion with the locals and the Rutland town meeting.[30]

Happily for Meresreau, on October 16, 1778, Congress resolved to send the Convention Army captives to Albemarle County, Virginia, for indefinite confinement.[31] In November, the remaining Convention prisoners, save for approximately 400 infirm and diseased men, set off on their march to Virginia. One of the sick who later escaped from captivity was Charles Stevens of the 24th Regiment of Foot. Given the irregularity with which the Continental officials managed to procure and distribute provisions and clothing in Rutland, Stevens was one of the lucky prisoners. In 1783 during a Board of Enquiry, he reported to the British Army that during his stay in Rutland he “Received a jacket, a yard & a quarter donation of legging cloth with buttons, needles & two pair of shoes, two pair coarse stockings, 7 yards of linen.”[32] For the rest of the Conventioneers, the journey to Virginia was to be long and arduous. 579 British and German troops made their escape along the way. Those who were not as lucky marched on, suffering beatings by their guards, the harshness of the elements, and the other dangers of their journey. At least two men drowned during river crossings, and a few ultimately succumbed to the weather and illnesses.[33] Once arrived, the remaining Conventioneers stayed in Virginia for three years. The remaining men endured the Convention Army’s last transfer, to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in 1781. The Conventioneers remained there for the rest of the war, whereupon the survivors were finally sent home.

Rutland continued to host a small portion of the Convention Army as well as prisoners of other conflicts until the war ended. In 1779, low provisions and a lack of guards made the local situation desperate. Under the terms of the convention of Saratoga, the British were to repay the Americans for supplies and provisions consumed by the captives, but that money was slow to come.[34] In an April letter to General Heath, Mersereau described “a deplorable situation” in Rutland, saying “the flour is almost gone . . . no hay, no thaw, and none to be got for paper money . . . wood cant be got without forage . . . what to do I can’t determine—I beg the favour of your Honor interposition with council in my behalf for relief.”[35] With little provisions to sustain them and better prospects beyond the barracks, many prisoners escaped in 1779. There were few guards to stop them. In the same letter, Mersereau relayed to Heath that the guards who had recently arrived were “almost all Boys & Children.”[36] Escapees included William Crooks from the 53rd Regiment of Foot, who made it to the British lines in New York and in 1783 told his story to Maj.Gen. Guy Carleton along with George Homes and Charles Stevens before a board of inquiry.[37] Though Heath had since relinquished his control of the Eastern Department and the Convention Army to Gen. Horatio Gates, Mersereau pleaded that Heath exert his influence over the situation. Gates responded by ordering the Conventioneers still in Rutland “to be brought to Boston, where it will undoubtedly be right to secure them in the Prison ship.”[38] The remaining Rutland Conventioneers were detained in Boston harbor for the rest of the war, awaiting the sooner of death or exchange.

***

When the war began, the Rutland town meeting happily sent men and money to the front, maintaining a short-lived, distant involvement in the conflict. Meanwhile, the Congress and the Continental Army had to manage an ever-growing number of captive soldiers. Rural towns like Rutland ultimately were the imperfect solution to this problem, with space to host the men and, in theory, ready provisions to support them. However, inhabitants and local leaders alike were not eager to welcome prisoners into their towns, and town meetings would not easily relent their authority to that of the Continental Army.

Despite this, the Revolution ultimately saw the Patriots seize power from Great Britain and local governments alike. By war’s end, the Rutland town meeting’s authority had been periodically superceded by that of the colonial government, and its autonomy had been forcibly qualified by the Continental Army’s management of the captive situation. The town meeting, defensive of its own authority, both participated in and overlooked hindersome behaviors to the army’s efforts. In so doing, it worsened the very position of authority that it was trying to protect, forcing Continental officials to turn to the colonial government for local interventions.

Rutland’s unique history calls for a broader study of the towns that hosted prisoners of war during the American Revolution. For many colonial towns, the outbreak of war meant an ongoing threat to traditional forms of local government. The intense way in which Rutland responded to this threat draws attention to the local experiences of the Revolution, and the forgotten pitfalls of the fight for colonial independence.

[1]Timothy Cornelius Murphy, History of Rutland in Massachusetts, 1713-1968 (Worcester: Rutland Historical Society, Inc., 1970), 21-22.

[2]Fred Anderson, A People’s Army: Massachusetts Soldiers and Society in the Seven Years’ War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1984), 29.

[3]Richard D. Brown, “Massachusetts Towns Reply to the Boston Committee of Correspondence, 1773,” The William and Mary Quarterly 25, no. 1 (January 1968): 23-26.

[4]Rutland town meeting to the Boston Committee of Correspondence, February 4, 1773, Rutland Town Records, Family Search, www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSQ7-T94Q-H?i=300, accessed February 4, 2019.

[5]John Nelson, Worcester County: A Narrative Historyvol. 1 (New York: American Historical Society, Inc., 1934), 214-215.

[6]Daniel Krebs, A Generous and Merciful Enemy: Life for German Prisoners of War During the American Revolution (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013), 104.

[7]Ken Miller, ‘“A Dangerous Set of People:’ British Captives and the Making of Revolutionary Identity in the Mid-Atlantic Interior,” Journal of the Early Republic 32, no. 4 (Winter 2012): 573. Also see Ken Miller, Dangerous Guests: Enemy Captives and Revolutionary Communities during the War for Independence (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014).

[8]“Continental Barracks,” The Massachusetts Spy, December 11, 1777.

[9]Resolve, April 4, I778, inThe Acts and Resolves, Public and Private, of the Province of the Massachusetts Bay (Boston, 1663), XX, 343, archive.org/details/actsresolvespass7778mass/page/342, accessed January 13, 2020.

[10]John Gooch to William Heath, April 21, 1778, William Heath Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, vol. 9, p. 264.

[11]Gooch to Heath, June 12, 1778, William Heath Papers, vol. 10, p. 69.

[12]Joshua Mersereau to Heath, April 22, 1778, William Heath Papers, vol. 10, p. 359.

[13]Gooch to Heath, September 18, 1778, William Heath Papers, vol. 9, p. 305.

[14]Joshua Davis to Heath, April 26, 1778, William Heath Papers, vol. 9, p. 305.

[15]Gooch to Heath, June 21, 1778, William Heath Papers, vol. 10, p. 124.

[16]Resolve, February 5, 1778, in Acts and Resolves, XX, 278, archive.org/details/actsresolvespass7778mass/page/278, accessed January 13, 2020.

[17]Mersereau to Heath, August 5, 1778, William Heath Papers, vol. 11, p. 16.

[18]Davis to Heath, July 16, 1778, William Heath Papers, vol. 10, p. 256

[19]William Tucker to Heath, August 22, 1778, William Heath Papers, vol. 11, p. 125.

[20]Board of Enquiry held at New York on Monday the 20th of Jany. 1783, and continued by Adjournment , PRO 30/55/6884, British National Archives.

[21]Nathan Tyler to Heath, July 24, 1778, William Heath Papers, vol. 10, p. 303.

[22]Heath to Tyler, August 4, 1778, William Heath Papers, vol. 11, p. 10.

[23]Heath to the Selectmen and Committees of Rutland, August, 1778, William Heath Papers, vol. 11, p. 9.

[24]Selectmen and Committees of Rutland to Heath, August 12, 1778, William Heath Papers, vol. 10, p. 63.

[25]Tyler to Heath, July 17, 1778, William Heath Papers, vol. 10, p. 273.

[26]Tyler to Heath, July 17, 1778, William Heath Papers, vol. 10, p. 273.

[27]Massachusetts Spy, July 16, 1778.

[28]Mersereau to George Washington, 31 August 1778. Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-16-02-0487, accessed November 17, 2018.

[29]Mersereau to the Massachusetts Council, August 31, 1778, William Heath Papers, vol. 16, p. 130.

[30]Nelson, Worcester County, 236.

[31]T. Cole Jones, Captives of Liberty: Prisoners of War and the Politics of Vengeance in the American Revolution, Early American Studies (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020), 171.

[32]Board of Enquiry held at New York.

[33]Jones, Captives of Liberty, 173.

[35]Mersereau to Heath, April 9, 1779, William Heath Papers, vol. 12, p. 286.

[36]Mersereau to Heath, April 18, 1779, William Heath Papers, vol. 12, p. 316.

One thought on “Rutland’s Rebellion: Defending Local Governance during the Revolution”

Great read! Thank you