The British approach to its American colony in 1775 offers valuable lessons for historians and military professionals in the synthesis between the levels of wartime leadership and their effect on direct action at the tactical level. As such, it is worthwhile to reflect on the British experience in 1775, and how guidance from strategic and operational leaders had a dramatic impact on the opening stages of the conflict. A misalignment of desired objectives, a desire to exercise control down to the lowest echelon, and poorly executed direct leadership defined the British approach concerning the events surrounding Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775.

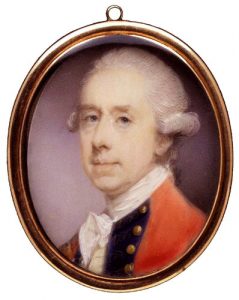

Examining written documents between British leaders in the Americas reveals a clear disconnect between the strategic and operational aims and offers the first example of misaligned objectives. Lieutenant General Thomas Gage was the Commander in Chief of all His Majesty’s forces in the American colonies and Governor of the Province of Massachusetts. Three days before the battle, on April 16, 1775, Gage received a letter from Lord Dartmouth, Secretary of State for the Colonies. Dartmouth, as one of King George III’s ministers, provided Gage with guidance on how he should employ the Crown’s military force for the “Kings Dignity, & the Honor and Safety of the Empire.”[1] Throughout his letter, Dartmouth vacillated between giving Gage outright operational direction and general strategic guidance.[2]

Dartmouth declared that his plan “will point out to you with precision the Idea entertained here, of the manner in which the Military Force under your Command may be employed with effect.”[3] After giving Gage detailed instructions on how to employ the military, Dartmouth then conceded that the actual utilization of his force depended on his “Discretion under many Circumstances that can only be judged of upon the Spot.”[4] Gage received a conflicting message from the Crown two days prior to combat operations. It dictated to him in detail an operational plan – that was somehow still left to his discretion. Rather than being presented with clear national strategic objectives within which to operate, Gage was directed on how to directly apply his military force down to the tactical level. Despite this unclear strategic guidance, he was given one clear objective by Dartmouth: arrest the leaders of the American Provincial Congress.[5]

Gage received much criticism for his operational leadership and his guidance to the tactical level in the days before the expedition. In the winter months before Concord, he repeatedly asked for direction and reinforcements, declaring that if England wanted to settle all disputes in America “you must conquer her, and to do that effectually . . . you should have an Army near twenty Thousand strong.”[6] While he waited for an answer, Gage formed his own opinions on how operations should be conducted in the spring which did not nest with the Crown’s. In February 1775 in a private letter to the Secretary at War Viscount William Barrington, he wrote of his desire to take the offensive, “for to keep quiet in the Town of Boston only will not terminate Affairs; the Troops must March into the Country.”[7] He believed that simply arresting the Provincial leaders would not be enough. Gage desired to pursue an aggressive offense as soon as possible, “for it is easier to crush Evils in their Infancy than when grown to Maturity.”[8] Interestingly, the second in command of the eventual expedition to Concord, Maj. John Pitcairn of the Marines, also struggled to understand the Crowns guidance towards combatting the rebellion. “I mean to seize them all and send them to England,” he wrote in February, then grudgingly conceded, “but we have no orders to do what I wish to do.”[9]

Over the winter months, through his intelligence apparatus, Gage learned of a large quantity of wartime materiel being stockpiled at Concord to support the Provincials.[10] With his understanding of actions that should be taken to quell the growing rebellion, he issued an order to the tactical commander for the upcoming planned expedition, Lt. Col. Francis Smith, commander of the 10th Regiment of Foot. In the second example of the misalignment of objectives, he disregarded the one piece of clear strategic guidance given—to arrest the leaders of Congress—and decided instead to seize this stockpile.

“Having received intelligence, that a quantity of Ammunition, Provisions, Artillery, Tents and small Arms, have been collected at Concord, for the Avowed Purpose of raising and supporting a Rebellion against His Majesty” began Gage’s tactical order to the seasoned military force under Smith. He continued,“you will March with a Corps of Grenadiers and Light Infantry, put under your Command, with the utmost expedition and Secrecy to Concord, where you will seize and destroy all Artillery, Ammunition, Provisions, Tents, Small Arms, and all Military Stores whatever.”[11] Gage concluded his order with, “You will open your business with the Troops, as soon as possible, which I must leave to your own Judgment and Discretion.”[12]

When viewing just these excerpts, Gage’s order is perfect. It gives his subordinate clear background, intent, guidance, and objectives, all while leaving the actual execution to the expeditioncommander’s control. However, it is the rest of the order that demonstrates how Gage, continuing the trend demonstrated by his higher leadership, dictated in detail down to the tactical level how he wanted Smith to accomplish the mission. He explicitly outlined how Smith’s men were to destroy the military stores. As an example, Gage instructed these experienced soldiers that any found “Powder and flower must be shook out of the Barrels into the River” and that the men “may put Balls of lead in their pockets, throwing them by degrees into Ponds, Ditches &c., but no Quantity together, so that they may be recovered afterwards.” Gage’s guidance was not limited to this, he also went so far as to instruct his subordinate commander on tactical terrain decisions on the ground, detailing how Smith should secure two key bridges and the way he should do it.[13]

Previous tactical orders to subordinates in the preceding months were short and concise; it now appeared that the strategic desire by his superiors to control actions at the lowest echelon spilled over into his instructions to his subordinate.[14] The veteran and seasoned soldiers of the British army in Boston did not need to be told how to destroy military stores, nor did its officers need to be directed how to control key tactical terrain. Despite this micromanagement, Gage did provide some commanders guidance, namely, to maintain secrecy, destroy found military stores, and to not plunder or destroy private property. With this order, Gage, rather than providing operational guidance and a framework within which to operate, descended to the lowest level and sought to instruct his subordinate on how to tactically execute the mission.

Leading up to the battle, Gage’s spy apparatus reported to him the exceedingly hostile countryside surrounding Boston.[15] His troops also conducted numerous marches throughout the areas surrounding the city, where militia would quickly and effectively muster and observe their every move.[16] In addition, a previous expedition sent to seize stockpiled military supplies in Salem in February 1775 was met with hostility by the local inhabitants.[17] As recently as March 30 (three weeks before Concord) a brigade marched into the countryside that “alarmed the people a good deal.” So much so that two cannons were loaded and staged at Watertown and a bridge was disabled leading into Cambridge, though the militias of either town did not physically engage the British.[18]

Through his spies, it appears that Gage also comprehensively understood the abilities and quick reaction times of the local militia. He warned in a letter to England of the Provincials’ abilities in “forming ambushments, whereby the light infantry must suffer extremely in penetrating the countryside.”[19] He earlier wrote to Dartmouth: “If force is to be used at length, it must be a considerable one, and foreign troops must be hired, for to begin with small numbers will encourage resistance.”[20] One of his subordinate officers, Brig. Gen. Hugh, Earl Percy, later described the colonists in a letter: “Whoever looks upon them as an irregular mob, will find himself much mistaken. They have men amongst them who know very well what they are about, having been employed as Rangers [against] the Indians and Canadians.”[21] Gage understood that any foray into the countryside would be immediately detected and could spark a conflict in which his force would be quickly outnumbered. Rather than empowering his tactical commander with this realistic intelligence assessment and overarching guidance in case of contact, Gage, like Dartmouth, immediately descended to the direct level of leadership in his order to his subordinate that stressed the seizing of the enemy’s military materiel above all else.

Gage would created a brigade size force consisting of the elite light infantry and grenadier companies pulled from their parent organizations. British infantry regiments in Boston contained one of each, normally composed of themost capable and sturdiest men in the regiment.[22] For this mission, these two elite companies from each regiment would operate together under one commander aligned against a specific mission set or objective. This was a common wartime practice, but the army had not been at war, and the companies in Boston had never operated in this manner. Though the soldiers, non-commissioned officers (NCOs), and officers from each company had trained with each other, they were not familiar with the leaders in the sister companies, or the officers appointed over the expedition. This meant that most of the men and leaders were not accustomed to working with the sister units that they were to depend on in combat.

To further compound the recently-created brigade’s command and control issues, several outside officers volunteered to join the expedition to fill shortages. While some thought this to be a bad idea, as one volunteer later wrote, it seemed best “for the Honor of the Reg’t” for the unit to march with a full complement of officers.[23] This included the second in command of the expedition, Major John Pitcairn of the Marines, assigned to command the battalion of light infantry companies; this was an odd choice, placing a Marine over the army. During the fight at the North Bridge another officer—who did not belong to a light infantry or grenadier company, but volunteered for the expedition—alluded to the unfamiliarity between the men and their leaders and its effect, describing how he “jumped over the hedge into a meadow just opposite the enemy as they were advancing and begged the [men] would follow me . . . which only three or four did.”[24] Despite their dedication to duty and competence, these leaders were unknown to the units they were attached to and therefore struggled to exercise control over the men during the fight.

The execution of direct leadership at the tactical level on April 19, 1775 suffered due to the improper synthesis between Gage and his subordinates and the unfamiliarity within the brigade. The overall performance of the British soldier was affected by this disconnect. Smith, chosen by Gage due to seniority, was to provide direct tactical leadership as the commander of the expedition. His first mistake was due to a poor understanding of the guidance instructing him to maintain secrecy. Despite Gage going to great lengths to maintain discretion due to his understanding of the capabilities of the Provincials, he failed to stress this effectively to Smith. From the onset of the mission, the alarm spread across the countryside like wildfire. Smith acknowledged this in his after-action report: “Notwithstanding we marched with the utmost expedition and secrecy, we found the country had intelligence or strong suspicion of our coming, and fired many signal guns, and rung the alarm bells repeatedly.”[25]

At this point, if Smith had possessed full knowledge of the intent and capabilities of the Provincials based on past actions and the intelligence that Gage had, he could have made the choice to turn back as some claim was suggested to him by several junior officers present.[26] An earlier an expedition tasked with a similar mission did return to Boston. Smith’s orders from his operational leader directed him to maintain secrecy, which obviously at this point no longer existed. However, due to the overly directive nature of Gage’s orders, he was hyper-focused on the mission to destroy the military stores at Concord, no matter the risk.

Smith, though praised by Gage in his after-action report, was not respected by many men on the expedition. It began with his physical appearance, which influenced a shared belief that he was exceedingly slow to react to any order and situation. Writings of subordinate officers and soldiers are riddled with criticism that began from the time the troops deployed and marched from Boston. One officer commented on Smith not being present when the skirmish occurred at Lexington: “Colo. Smith was not then in front, owing to the fast march of his troops, and his being a heavy man.”[27] His weight was further blamed for his slowness to provide reinforcements at the North Bridge: “The Colonel ordered 2 or 3 companies, but put himself at their head, by which means stopt ‘em from being time enough, for being a very fat man he would not have reached the bridge in half an hour.”[28] During the retrograde from Concord back to Boston, Smith lost all command and control of his men due to his perceived slowness and inability to coordinate efforts and provide direct leadership at the tactical level. One officer after the engagement concluded “An Officer of more activity than Col Smith, should have been selected for the Command of the troops destined for this service.”[29]

The example set by the commanding officer was not lost on the men, as demonstrated by their performance. Without debating who fired the first shot at Lexington, the British army, as noted by Pitcairn, “without any order or regularity . . . began a scattered fire and continued in that situation for some little time, contrary to the repeated orders both of me and the officers that were present.”[30] Another officer wrote, “the men were so wild they could hear no orders.”[31] Smith himself later commented on his desire to regulate the uncontrolled rage of his men at Lexington as he “was desirous of putting a stop to all further Slaughter of those deluded People.”[32]

Facing the Provincials at the North Bridge in Concord, the men under the command of Capt. Walter Laurie after having traded a “general popping” of fire conducted a disorderly self-initiated retrograde for “which the whole went to the right about, in spite of all that could be done to prevent them.” It would not be until his force again linked up with Smith that Laurie regained order over his troops.[33] The Provincials also noted the confusion in the British ranks, one witness remarking that they showed “great fickleness and inconsistency of mind, sometimes advancing, sometimes returning to their former posts; till at length they quitted the town and retreated by the way they came.”[34] Another commented that he witnessed the British “a running and a Hobbling about, looking back to see if we was after them.”[35]

Due to the different companies’ unfamiliarity the men’s performance and team effort suffered greatly throughout the fight. In addition to this, the clear and concise intent that direct leadership must provide was lost. Upon completion of the only objective that was met—the destruction of military stores—the disorganized scramble back to Boston began. A junior officer in the 10th Regiment of Foot wrote later in his diary that though the British soldiers displayed great personal courage they “were so wild and irregular, that there was no keeping ‘em in any order.”[36] During the retreat back to Boston, the British force disintegrated into a fleeing mob: “we began to run rather than retreat in order . . . we [the officers] attempted to stop the men and form them two deep, but to no purpose.” It became so bad the “officers got to the front and presented their bayonets, and told the men if they advanced, they should die. Upon this they began to form under a very heavy fire.”[37]

As the force moved back to Boston, the operational guidance to not destroy or plunder private property was soon disregarded as well, triggered by a tragic event. As the British retreated from the North Bridge, leaving behind their casualties, a wounded soldier was cruelly dispatched with a hatchet blow from a Provincial private.[38] A rumor consequently spread throughout the ranks that British wounded and prisoners were “afterwards scalped, their eyes goug’d, their noses and ears cut off.”[39] This, combined with the past months of escalating tensions in the region, and the irregular tactics utilized by the Provincials that day, caused the British soldiers to become so “enraged at suffering from an unseen enemy that they forced open many of the houses from which the fire proceeded, and put to death all those they found in them.”[40] Furthermore, “Many houses were plundered by the soldiers, notwithstanding the efforts of the officers to prevent it.”[41] Another officer noted that “the plundering was shameful; many hardly thought of anything else; what was worse they were encouraged by some officers.”[42]

Despite the historical debates over how much murder and plundering occurred, it did happen. This was due to the inability of direct leadership at the tactical level to control their men and keep them within the operational-level intent communicated to them. The disconnected way the expedition was established resulted in several officers not knowing their commands, some soldiers not trusting their leaders, and an overall lack of unity of effort amongst the different companies. After the engagement the men were rebuked by Gage, who issued a statement:

As by the report from Lord Percy and the Officers in general, the men in the late affair, tho they behaved with much courage and spirit, shewed great inattention and neglect: to the Commands of their Officers, which if they had observed, fewer of them would have been hurt, the General expects on any future occasion, that they will behave with more discipline and in a more Soldier like manner: and it is his most positive orders that no man quit his rank to plunder or pillage, or to enter a house unless ordered so to do, under pain of death; and each Officer will be made answerable for the Platoon under his Command.[43]

The shock of leaving Boston as soldiers in peacetime and retreating to the city as a nation at war may have contributed to the hectic actions of the men. Gage would later remark to Barrington, “People would not believe that the Americans would seriously resist if put to the test, but their Rage and Enthusiasm, appeared so plainly.”[44] Percy wrote in astonishment, “For my part, I never believed, I confess, that they wd have attacked the King’s troops, or have had the perseverance I found in them yesterday.”[45] After the defeat another British participant seethed over the Provincials, his shock and dismay spilling from the page: “they are the most absolute cowards on the face of the earth.”[46] Finally, one witness succinctly concluded, “A good deal of this unsteady conduct may be attributed to the sudden and unexpected commencement of hostilities, and the too great eagerness of the Soldiers in the first Action of a War.”[47]

Despite the poor direct leadership at the tactical level demonstrated by Smith, numerous individual positive examples did occur. Brigadier General Percy was tasked as the commander of a relief force if needed. Regardless of critical critiques of his reaction time in responding to Smith’s plea for assistance, he performed exceptionally well on the direct level. He was cited by numerous contemporaries for bravery and is credited with saving Smith’s force from annihilation. One of his subordinates wrote that Percy “shewed the greatest personal Courage was every where there was any danger & sat his Horse the whole time which considering our situation was rather too conspicuous a Place.”[48] Gage, in his report to the ministers, wrote: “Too much praise, cannot be given to Lord Percy, for his remarkable Activity and Conduct, during the whole day.”[49]

Superb direct individual leadership was not limited to Percy; it also extended to many of the junior officers, NCOs, and soldiers present, as illustrated by an examination of the casualty count for the expedition. Gage reported 73 killed, 174 wounded, and 26 missing out of an estimated 1,800.[50] From those numbers 28 were NCOs and above.[51] Stories abound of junior leaders exposing themselves to danger when trying to rally their troops. One participant noted an “officer, mounted on an elegant horse, and with a drawn sword in his hand” conspicuously riding back and forth trying to exhort his troops, where soon a number of Provincials “raised their guns and fired with deadly effect.”[52] These leadership examples inspired the men to not shirk their duty; “I had my hat shot off my head three times, two balls went through my coat, and carried away my bayonet by my side,” described one British soldier who unflinchingly faced fire.[53] This trend continued to the next engagement, the Battle of Bunker Hill, where 92 officers were killed, a figure which shocked senior officers. Later, British Gen. William Howe wrote, “when I look to the consequences of it, in the loss of so many brave officers, I do it with horror. The success is too dearly bought.”[54]

In a propaganda narrative created by the Provincial Congress following the events at Lexington and Concord and distributed in England to influence the informational environment, a curious event was recounted in one of the depositions. Thomas Willard, a witness to the actions at Lexington, wrote of a British officer who exposed himself to danger and rode out in front of the main body, and engaged the Provincial militia to prevent further bloodshed; in disbelief he exclaimed, “Lay down your arms, damn you, why don’t you lay down your arms.”[55] In addition, one officer wrote of the retreat: “whenever an officer run out to clear any place he had a hundred at his heels not of his own Men but of a dozen different Regiments.”[56] Men like Percy and even the much-criticized Smith gave up their horses for wounded enlisted soldiers, and one private wrote home about his commander giving him some brandy from his personal canteen.[57] The casualty numbers and these actions speak to the tenacity, fighting spirit and lead-from-the-front attitude that the British junior officers, NCOs, and soldiers exhibited during the engagement. Actions like these from junior leaders present were the norm rather than the exception—if only this tenacity could have been coordinated and harnessed by an effective operational leader.

“Thus ended this Expedition, which from beginning to end was as ill plan’d and ill executed as it was possible to be,” declared one junior officer.[58] Dartmouth, shocked by the events of the day and the disregard of his guidance, wrote to Gage on his decision to move on Concord, concluding, “if from the Probability of small Advantage on the one hand, and great Risk on the other hand, you should have desisted from such an Enterprize.”[59] With the events at Concord combined with the pyrrhic victory at Bunker Hill in June 1775, it was decided that Gage was to no longer to serve in the colony. Dartmouth, under the guise that Gage was to return to advise the Crown on future operations, in a silver-tongued relief letter informed him that the King had concluded, “you have little Expectation of effecting any thing further this Campaign” and directed Gage to return to England as conveniently as possible.[60]

Gage would soon return to England, but not before offering his opinion to the Secretary at War. “I thought I foresaw the storm gathering many Months ago,” Gage would gracefully remind Barrington, “when I took the Liberty to tell your Lordship that no Expense should be spared to Quash the Rebellion in it’s Infancy.” The dye for war was cast, he ominously concluded, “and tho’ the Rebels have been better prepared than any Body would believe,” the state of affairs was not irreversible—if only the nation would exert her full military force as he had advised from the beginning, America could be brought back under British control.[61]

A misalignment of desired objectives, a desire to exercise control down to the lowest echelon, and poorly executed—though tenacious—direct leadership defined the British approach to the events of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775. This combination also failed to effectively provide clear intent, purpose, and senior role models during the operation, which sealed the defeat. The British at the beginning of the American Revolution provide an excellent historical case study to understand how the levels of leadership exert an influence on each other, and how they can affect execution at the direct level. The events surrounding the first engagement of the American Revolution illustrates how overly directive military orders from strategic leaders can hamper initiative and direct action with disastrous results.

[1]Secretary of State for the Colonies Lord Dartmouth to General Gage, January 27, 1775, in Vincent J-R Kehoe, The British Story of the Battle of Lexington and Concord on the Nineteenth of April 1775 (Los Angeles, CA: Hale & Company MM, 2000), 4.

[2]Lord Dartmouth to General Gage, ibid., 6.

[5]Arthur B. Tourtellot, Lexington and Concord, The Beginning of the War of the American Revolution (London: Norton & Company, 1959), 87.

[6]Thomas Gage, “Private Letter to Barrington, October 3, 1774”, in The correspondence of General Thomas Gage with the Secretaries of State, and with the War Office and the Treasury, 1763-1775, Clarence E. Carter, ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1933), 2: 656.

[7]Thomas Gage, “Private Letter to Barrington, February 10, 1775”, in The correspondence of General Thomas Gage, 2: 669.

[8]Thomas Gage, “Private Letter to Barrington, March 28, 1775”, in The correspondence of General Thomas Gage, 2: 671-672.

[9]Maj. John Pitcairn, “LetterTo the Earl of Sandwich,” in Henry Steele Commager, Richard B. Morris, ed., The Spirit of Seventy-Six, The Story of The American Revolution as Told by its Participants (New York: NY, 2002), 62.

[10]Orders from General Gage to Lieutenant Colonel Smith, April 18, 1775, in Kehoe, The British Story, 13.

[14]General Thomas Gage, Early American Orderly Books, Daughters of the American Revolution Library, reel 1.

[15]An Account of the Transactions of the British troops, from the time they marched out of Boston, on the evening of the 18th, “till their confused retreat back, on the ever memorable Nineteenth of April 1775 ; and a Return of their killed, wounded and missing on that auspicious day, as made to Gen. Gage (Boston: MA, 1779), 14-15, www.masshist.org/revolution/image-viewer.php?item_id=516&mode=small&img_step=14&tpc=#page14, accessed August 24, 2019.

[16]Frank Warren Coburn, The Battle of April 19, 1775, In Lexington, Concord, Lincoln, Arlington, Cambridge, Somerville and Charlestown, Massachusetts (Lexington, MA: By the Author, 1912), 16. Also described by Frederick Mackenzie, A British Fusilier in Revolutionary Boston, Allen French, ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1926), 32-33, 44, 70.

[17]Charles M. Endicott, Account of Leslie’s Retreat at the North Bridge in Salem (Salem, MA: Wm. Ives and Geo. W. Pease Printers, 1856), 26-34.

[18]Lt. John Barker, The British in Boston, Elizabeth E. Dana, ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1924), 27-28.

[19]Tourtellot, Lexington and Concord, 90.

[21]Lord Percy to General Harvey, April 20, 1775, in Kehoe, The British Story, 91.

[22]Rev. William Gordon, “Letter to Gentleman in England,” in Commager and Morris, The Spirit of Seventy-Six, 78.

[23]Ensign Jeremy Lister, “Personal Papers,” National Park Service (2017): 2, www.nps.gov/mima/learn/education/upload/Ensign%20Jeremy%20Lister.pdf, accessed October 13, 2019.

[24]Lt. William Sutherland, “British Officer, 38th Regiment of Foot,” National Park Service (2017): 1, www.nps.gov/mima/learn/education/upload/Lt.%20William%20Sutherland.pdf, accessed October 13, 2019.

[25]Report from Lieutenant Colonel Smith to General Gage, no date, in Kehoe, The British Story, 52.

[26]Mackenzie, A British Fusilier in Revolutionary Boston, 63.

[28]Lt. John Barker, “Diary of a British Officer,” in Commager and Morris, The Spirit of Seventy-Six, 71.

[29]Mackenzie, A British Fusilier in Revolutionary Boston, 71-72.

[30]Maj. John Pitcairn, Report to General Gage, Digital History (2019): 1, www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/active_learning/explorations/revolution/account3_lexington.cfm, accessed October 14, 2019.

[31]Barker, “Diary of a British Officer,” 71.

[32]Vincent J-R Kehoe, We Were There, April 19th 1775 (Somis, CA: Vincent J-R Kehoe, 1974), 75.

[33]Capt. Walter S. Laurie, Letter to General Gage, National Park Service (2017): 1, www.nps.gov/mima/learn/education/upload/Captain%20Walter%20Laurie.pdf, accessed October 11, 2019.

[34]William Emerson, “Description of the Stand at Concord Bridge,” in Commager and Morris, The Spirit of Seventy-Six, 85.

[35]Ellen Chase, The Beginnings of the American Revolution, Based on Contemporary Letters Diaries and Other Documents, Vol. II (New York, NY: The Baker and Taylor Company, 1910), 39.

[36]Barker, The British in Boston, 39.

[37]An Account of the Transactions of the British troops, 19, www.masshist.org/revolution/image-viewer.php?item_id=516&mode=small&img_step=19&tpc=#page19, accessed August 24, 2019.

[38]Kehoe, The British Story, 56.

[39]Lister, “Personal Papers.”

[40]Mackenzie, “Diary of a British Officer,” in Commager and Morris, The Spirit of Seventy-Six, 87.

[42]Barker, The British in Boston, 39.

[44]Thomas Gage, “Private Letter to Barrington, June 12, 1774,” in The correspondence of General Thomas Gage, 2: 684.

[45]Hugh, Earl Percy, Letters of Hugh Earl Percy from Boston and New York 1774-1776, Charles Knowles Bolton, ed. (Boston, MA: Charles L. Goodspeed, 1902), 53.

[46]Capt. W.G. Evelyn, “Letter to the Reverend Doctor Evelyn,” in Commager and Morris, The Spirit of Seventy-Six, 89.

[47]Kehoe, The British Story, 67.

[48]British officer part of Percy’s command, author and date unknown, in Kehoe, The British Story, 77.

[49]Gage to Barrington, April 22, 1775, in Kehoe, The British Story, 94.

[50]Tourtellot, Lexington and Concord, 202.

[51]An Account of the Transactions of the British troops, 20, www.masshist.org/revolution/image-viewer.php?item_id=516&mode=small&img_step=20&tpc=#page20, accessed August 24, 2019.

[52]Ezra Ripley, A History of the Fight at Concord on the 19th of April 1775 (Concord, MA: Allen and Atwil, 1827), 34.

[53]Kehoe, We Were There, 170.

[54]Sir William Howe, “Letter to the British Adjutant General,” in Commager and Morris, The Spirit of Seventy-Six, 132.

[55]Narrative, of the Excursion and Ravages of the King’s Troops Under the Command of General Gage. on the nineteenth of April, 1775. Together with the Deposition Taken by Order of Congress, to support the Truth of it (Boston: 1775), 6, www.masshist.org/revolution/image-viewer.php?item_id=627&mode=large&img_step=6&tpc=#page6, accessed August 24, 2019.

[56]British officer part of Percy’s command, author and date unknown, 76.

[57]Unidentified soldier in Percy’s command to family, August 20th, 1775, and Journal of Ensign Lister, date unknown, in Kehoe, The British Story, 63, 78.

[58]Barker, The British in Boston, 37.

[59]Lord Dartmouth, “Dispatch to Honorable Lieutenant General Gage, July 1, 1775”, in The correspondence of General Thomas Gage, 2: 200-201.

[61]Thomas Gage, “Private Letter to Barrington, August 19, 1774”, in The correspondence of General Thomas Gage, 2: 696.

7 Comments

As one whose profession demanded cultural understanding of the adversary, I have long argued that British Georgian culture and history as understood by British Government and military officials insured they did not understand that the American colonial was a different person than the British islander. This is the larger picture and the strategic reason Britain lost its American colonies.

Very thoughtful article. Contemporary joint military doctrine emphasizes an understanding the operational environment, strategic guidance and a clear statement of the problem to be solved before developing an operational approach. As Ken Daigler points out, the individuals who provided both policy and strategic guidance to the tactical military operators lacked an appreciation of the nature of the environment and the problem. The American people viewed themselves as citizens, the British Government viewed them as subjects. David Hackett Fischer provides an example of this in “Paul Revere’s Ride” (Oxford Univ. Press 1994, pp. 163-4), where he describes an interview with 91 year-old Captain Levi Preston of Danvers, MA, about why he went to the Lexington and Concord fight on 19 April 1775. “Captain Preston, what made you go to the Concord Fight?” After several probing questions the aged warrior responded. “We always had governed ourselves and we always meant to. They didn’t mean we should.” As in 1775, it is dangerous to assume there is a military solution to all political problems.

Excellent article and great lessons for all leaders on the need for clear objectives and clear direction!

Although in the British military for over 30 years, I believe that this battle was the first combat experience for Lt. Col. Francis Smith. Likely, this lack of battlefield command experience also contributed to his failed direct leadership. On the other hand, Lord Percy was a veteran of the European battlefields (and higher in rank) which contributed to his able command of the relief force and his more proficient leadership of the ultimate retreat to Boston.

I can’t prove this, but wonder if the Rebels, soldier for soldier, had more combat experience than the British?

Gene’s point about combat experience is always on my mind. I seem to remember Don Hagist–who probably knows more about the British military of the time at both the grand and grass-roots levels–commenting that the army of 1775 actually had few men with much combat experience within its ranks.

To add to the mental mix of the colonial soldier, much of American society had been “fighting” the home government for several years. Further, the American drive to improve themselves had imbued something of an aggressive element in society’s nature. In the extreme cases of the latter, those on the frontier fought every day just to survive. It seems to me that life in England lacked these elements.

I enjoyed the article and agree with its premise. It has me wondering about the British collection of orders for other campaigns and battles. Does a similar micromanagement pattern appear?

On a minor detail, I question the comments about Smith’s physical abilities affecting the force’s performance. I interpret the negative comments on his “activity” as being directed not at his physical but, rather, his mental performance. Although at some point he may have given his horse to a wounded soldier, he sat on a horse for most of the day. Being overweight would not matter in that condition.

Lastly, I like the comment about the officers threatening the men with their bayonets. Shows they carried firelocks and not spontoons contrary to the opinions of some folks (I spend a lot of time in the reenactment community).

I have heard that the British were purposely given the intelligence to encourage them to march out of Boston. An incident was needed to force a decision in Philadelphia. ???

In my mind, the biggest disconnect in the war’s early days wasn’t between Gage and his troops, but between Gage and London. To be sure, Gage sent Smith off with mixed expectations, but that always seemed to be more a function of: 1) uncertainty about the operational environment in MA; and, 2) English military culture, from which the Americans also suffered.

The main problem was London’s belief it could subdue the Americans easily with a firm hand and the arrest of a few ringleaders. Gage recognized he had a bigger problem and that the Americans had both the will and ability to resist military efforts. Thus, his constant pleas for more troops and his efforts to round up arms on several occasions before Lexington and Concord. But, his tendency to hedge and tell London what it wanted to hear about a “firm hand’ being the best policy offset his pleas. London split the difference, sending more troops, but never enough for the war Gage warned about. The conflicted guidance provided to Gage had more to do with avoiding responsibility, and blame, for either escalating the war or underestimating its difficulty.

Gage owns that confusion in part due to his mixed messaging, but it’s understandable in an uncertain and fluid political environment.

I often wonder how things might have turned out if Gage had marched with the column and then paused to reassess things at Lexington after the shooting started rather than indifferently pressing on to Concord.