Lord Stirling was not happy. The American brigadier general[1] was on a mission from George Washington to inspect the newly built fortifications in the Hudson Highlands of New York. As he sarcastically wrote Washington in early June 1776

the Westermost Battery is a streight line constructed by Mr Romans at a very great Expence, . . . and can only annoy a Ship in going past . . . . [It] looks very picturesque, upon the whole Mr Romans has displayed his Genius at a very great Expence, & very little publick Advantage. The Works in their present open Condition, and scater’d Situation, are defenceless; nor is there one good place on the Island on which a Redoubt may be erected that will Command the whole . . . Yet every work on the Island is Commanded by the Hill on the West point, on the opposite side of the River, within 500 yards . . . a Redoubt on this West point is absolutely necessary, not only for preservation of Fort Constitution, but for it’s own importance on many accounts.[2]

Lord Stirling was upset about the condition of the only defensive barrier on the Hudson River a little over a year since the opening battle of the Revolutionary War at Lexington. Soon after the battle the Continental Congress and George Washington had both quickly seen that it was imperative to fortify the Hudson Highlands around West Point in order to prevent the British from quickly gaining control of the river and cutting of New England from the rest of the colonies.

West Point during the Revolution is usually thought of today as a superb example of eighteenth-century military fortification. It has been described as “far ahead of its time” and “revolutionary, complex, and elegant.”[3] George Washington himself in 1783 called West Point the “key of America; It has been so pre-eminently advantageous to the defence of the United States.”[4] Additionally, West Point is one of the oldest continually occupied military posts in the U. S.[5] However, the job of fortifying the Hudson Highlands did not begin well. These early efforts are not well known today and provided many lessons for the future conduct of the war.

Bernard Romans, From Surveyor to Military Engineer

The first person hired to build the necessary defenses along the Hudson was a Dutch born surveyor, cartographer, and botanist named Bernard Romans. No portrait or written physical description exists of him and much of his early life is a mystery. He was born in Delft, The Netherlands, on June 7, 1741, and immigrated to England when young to study mathematics and botany and some engineering. In 1756 he moved to the British American colonies to take a civil service job as a junior surveyor. For the next fifteen years Romans spent most of his time in the southern colonies, particularly Florida. By 1768, in addition to slave trading and small time land speculation, the British government had appointed him principal deputy surveyor for the “Southern District of British North America, and first commander of the vessels on that service.”[6]

Romans’s responsibilities included the new colonies of East and West Florida, given to Great Britain by the treaty ending the Seven Years War. Exploring the Floridas’ interior and coastlines he attempted to fill in the blank spaces on the existing Florida maps. Romans possessed an argumentative personality and it rose to the surface quite frequently. In 1770 he quarreled with his boss John William Gerard de Brahm as well as Georgia’s governor James Grant and was fired from government service by Lord Hillsborough, Secretary of State for the American Department and president of the Board of Trade.

Romans was quickly rehired by John Stuart, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Southern District, to survey the interior of West Florida, which he explored by canoe and also charted Pensacola and Mobile Bays. His explorations resulted in his producing a forty square foot map titled “General Map of West Florida—the Whole Examined and Carefully Connected at Pensacola on August 31, 1772” that earned praise from West Florida’s governor.[7]

During this period Romans left evidence of his contrary disposition by writing the Colonial Office about the natives and the white traders from South Carolina and Georgia. Concerning Native Americans he wrote that “A great deal has been said by Many Writers that the natives are a very good, Simple, honest and even virtuous people. I must Contradict them, and Say that they are Treacherous, Cruel, deceitfull, Faithless and thieving.” As for traders he felt that “The Behaviour of the Vile Race who now carry on that Business, is such that a relation of it in the most favourable Manner could not fail to Shock humanity. Nay, the very Savages are scandalized at the lives of those Brutes in human shape, the very scum and outcast of the Earth, always more prone to savage barbarity than the savages themselves.”[8]

After almost twenty years exploring and mapping the Southeast, a pay dispute led Romans to decide to sail from Charleston to New York City and start over. When Romans arrived in New York City in the early summer of 1773 he quickly advertised in local papers his plan to publish a book titled Concise Natural History of East and West Florida along with two large maps that covered both Floridas. Romans received many subscriptions, including New York’s Governor William Tryon. The maps, twenty-seven and a half and thirteen and a half square feet, were used by many ships’ captains because they covered 600 miles of Florida east to west and 900 miles north to south. Romans’s cartography work so impressed the American Philosophical Society, the most respected and influential scientific body in America at that time, that they elected him a member.

Romans soon after moved to Boston where he met people who would be leading the early revolutionary effort in Massachusetts. He hired Paul Revere to engrave his two map sheets while John Hancock bought two subscriptions to Romans’s book and maps. Henry Knox bought fifty books for his bookstore. Concise Natural History was a success when it was published in 1775 and is currently recognized as an important book in Colonial America despite accusations at the time of Romans having plagiarized much of the book.

Fifty-five and unmarried, Romans settled in Wethersfield, Connecticut, and began to espouse revolutionary ideas.[9] It’s uncertain why Romans decided to join the Patriot cause at his age. Perhaps his time with the leading rebels in Boston swayed his thinking. His difficult relations with his British superiors while a government employee may have played a role. Whatever motivated him, Romans was prepared to join the rebel cause.

Romans presented himself to the Connecticut Committee of Safety less than a week after Lexington and Concord. The Committee determined that Romans should lead a military expedition from Hartford against Fort Ticonderoga and Crown Point to capture the cannons there. This was not a unique idea. Benedict Arnold also had this in mind. The Committee of Safety gave Romans a captain’s commission on April 27, 1775 and sent him north towards Ticonderoga with one hundred pounds and told him to recruit a force along the way. Romans had enlisted more than 200 volunteers when Col. Ethan Allen and Colonel Arnold joined Romans’s group. Arnold and Allen disputed who should command the combined forces. Allen won the dispute and Romans was completely ignored and pushed aside.[10] Romans’s irritable nature reasserted itself with Capt. Edward Mott recording that “Mr. Romans left us and joined no more; we were all glad, as he had been a trouble to us, all the time he was with us.”[11]

Now on his own, Romans and sixteen volunteers he collected on the way captured the abandoned Fort George, fifty miles from Ticonderoga, which was in the sole possession of a sixty-five year old retired British Army captain and his aide. Romans traveled to Ticonderoga on May 14 with his pride restored and helped inventory the weapons there.[12] Arnold was impressed with his efforts and stated that Romans was “a very spirited, judicious gentleman who has the service of the country much at heart.”[13]

Writing to the Massachusetts Committee of Safety, Arnold said that Fort Ticonderoga was “next to impossible to repair . . . . I have the pleasure of being joined in that statement by Mr. Romans, who is esteemed an able engineer.”[14] Perhaps Arnold’s praise of Romans’s engineering abilities gave him the idea he was a capable military engineer.

The First Attempt to Fortify the Hudson Highlands

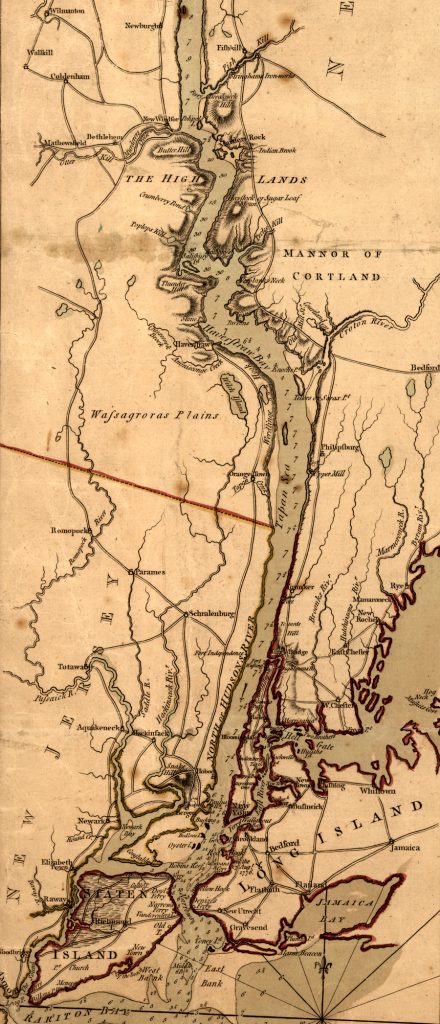

The Hudson Highlands are a mountainous belt of granite and gneiss that form a fifteen mile barrier across the Hudson River approximately sixty miles north of Manhattan Island. The deep gorge of the Hudson River, high mountains on both sides of the river and several small rocky islands are characteristic of the area. Glacial terraces are also common such as the area around West Point.[15]

On May 23, 1775 New York Radicals established their legislative body called the Provincial Convention.[16] Two days later the Continental Congress passed a list of seven resolutions asking the New York Convention to block the Hudson due to fears of a British invasion to recapture Ticonderoga.

The Convention chose Col. James Clinton and Mr. Christopher Tappen, both New York delegates and Hudson Valley residents, to “go to the Highlands and view the banks of the Hudson River there, and report to this Congress the most proper place for erecting one or more fortifications; and likewise an estimate of the expense that will attend erecting the same.”[17]

Clinton and Tappen explored both “the West Point” and Constitution Island on June 2. Constitution Island lies just to the north of where West Point juts into the river and is separated from the eastern bank of the Hudson by a marsh. West Point drew their attention due to its dominance of the river, how the river narrowed there, the zig-zag course of the river had to take around West Point and the three feet high tides. They also felt Constitution Island was good for fortification because it had previously been inhabited, and thus was livable. They left believing both West Point and Constitution Island should be fortified with forts and artillery batteries and also with some kind of obstruction in the river between the two areas.[18]

The Convention then promptly forgot about the Highlands until August 17 when George Washington prodded them into action. They appointed a Commission of five, later seven, members to supervise the work. The Commissioners were to operate quasi-independently and were to recruit workers, manage the payments and oversee the construction of the fortifications.[19]

This command arrangement was a disaster waiting to happen. It was a violation of the principle of war of unity of command. There was no single person in charge of the operation, and the arrangement did not take into account where the project engineer fit into the chain of command. Additionally, trained engineers were very rare in the colonies, let alone a military engineer.[20]

On this point George Washington was desperate. He expressed his frustration to John Hancock. “In a former Part of this Letter I mentioned the Want of Engineers; I can hardly express the Disappointment I have experienced on this Subject: The Skill of those we have, being very imperfect & confined to the mere manual Exercise of Cannon . . . . If any Persons thus qualified are to be found in the Southern Colonies, it would be of great publick Service to forward them with all Expedition.[21]

Around this time Bernard Romans heard that New York wanted an engineer to fortify the Hudson Highlands. He probably considered himself highly qualified for the job since he had twenty years’ experience surveying and mapmaking in the South. He also had earned praise from Benedict Arnold at Fort Ticonderoga for his engineering skills. Always chronically short of money, Romans arrived in Philadelphia to lobby for the job. Impressed with his membership in the American Philosophical Society and needing an engineer, Congress hired him.[22]

During the second week of September Romans arrived in New York and he and three Commissioners, Samuel Bayard, William Bedlow, and John Hanson left for the Highlands. Upon arrival Romans and the Commissioners moved into the abandoned farmhouse on Constitution Island and agreed on what structures to build and their locations.[23]

On the island they discovered that the west and northwest sides of Constitution Island had cliffs that were too high to be of use and the highest point on the island was 134 feet. With a circumference of two miles and a width of half a mile north to south, the island was surrounded by the Hudson River on all sides except for the east where a marsh connected it to the east bank of the river.[24]

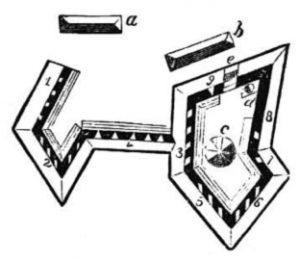

Romans soon became convinced that the original plan recommended by Clinton and Tappen and approved by the Provincial Convention and Commissioners was wrong. He decided, without informing the Commissioners, to abandon the plan for obstacles in the river and that only a blockhouse with four light cannons and a battery of three six-pounder guns were necessary on West Point. He placed all emphasis on Constitution Island and planned four blockhouses, four batteries, and a bastioned fort called the “Grand Bastion,” or Fort Constitution, that would be protected by an outer stone wall thirty feet thick, eighteen feet high, and five hundred feet long. Romans felt firepower alone would do the job of stopping ships in the river.[25]

Romans quickly returned to New York and presented his revised plans to the Committee of Safety. The Committee of Safety assumed the plan was fine with the Commissioners and approved the plan on September 19 and forwarded it to the Continental Congress.[26]

Word reached the three Commissioners on September 24 of Romans’s change in plan. Extremely angry, all three signed a sarcastic and angry letter to the Committee of Safety. “We should have esteemed ourselves happy had we been consulted on this subject before it had been sent forward.” They also demanded to know who was in charge of the project. “Inform us whether we are under Mr. Romans’ direction, or whether he is obliged to consult with us upon the measures pursued.”[27] Not having a single person in charge was beginning to cause problems.

When word of the Commissioners’ anger reached the Committee of Safety, Romans boldly asked the Committee to make him the contractor for the whole project for £5,000 as well as making him the sole manager of the project while the Commissioners’ responsibility was reduced to managing the logistics of the operation. The next day the Committee of Safety rejected Romans’s offer as well as his demand for a colonel’s commission. Romans returned to the Highlands and he and the Commissioners attempted to work together after the Committee of Safety informed the Commissioners to work with Romans since he was “to proceed to you, and give his best advice and assistance, as an engineer.”[28]

Meanwhile the Continental Congress debated how to best complete the Highlands project. Congress appointed a committee to review the matter and on October 7 the committee recommended that work continue under the supervision of the Convention, and that other places should be fortified in addition to Constitution Island. They concluded by telling the Convention “to take the most effectual method to obstruct the navigation of the Hudson River.”[29] The Convention quickly told the Commissioners to carry out Congress’ request and also stated “you will take Mr. Romans to your assistance.”[30]

For a few weeks that fall Romans and the Commissioners got along and sought to pacify the Congress. They told Philadelphia that blocking the Hudson would “be an easy matter” but also disregarded Congress’ idea of additional fortifications near Constitution Island and instead suggested fortifying the river across from Anthony’s Nose and near Popolopen Creek, approximately seven miles downriver from Constitution Island.[31]

Romans’s and the Commissioners’ reply to Congress generated a false sense of optimism that the work would be finished by December. In reality, construction was just creeping along. Romans lacked professional engineering expertise which led to overly optimistic schedules and a lack of progress. He was also by now claiming the unauthorized rank and privileges of a Continental colonel which further deteriorated his relationship with the Commissioners. Other issues arose as well. The Convention wouldn’t let rum be sold at the work site so workers were constantly looking for drink. Reports of black market activity, overpayment for supplies, and contractors suppling spoiled food to the workers also occurred. The Convention questioned none of this.[32]

As winter approached, everyone on Constitution Island realized the work would not be finished by December. Romans blamed the Commissioners and they blamed him. Romans moved into a finished blockhouse while the Commissioners remained in the abandoned farmhouse. Instead of talking to each other they began sending angry written messages to one another. Romans called it an “epistolary altercation” with many harsh words exchanged between the two sides. The Commissioners angrily castigated Romans for his vanity and idiosyncrasies. Romans replied to the Commissioners about their faults and lack of good judgement. The Commissioners even wrote to Romans that his slave was as disliked as he was. Much of the bile concerned long lists of disagreements about the work, cost, and minor items relating to building techniques. Work at the site slowed to a standstill.[33]

News of the feuding on Constitution Island reached Congress in Philadelphia. In response Congress appointed a three man committee of Robert Livingston, John Langdon, and Robert Treat Paine on November 8 to travel to the Highlands and evaluate the situation and report their findings back to Congress.[34]

The Committee was shocked and upset at conditions on Constitution Island. Romans’s optimistic progress reports were seen to have been false and that over 200 workers and soldiers had only been working on “barracks, the block-house, and the southwest curtain.” Additionally, work on the main fortification, the “Grand Bastion” had not even started. Upon checking fields of fire for the seventy-one emplaced cannons, they discovered that a ship sailing upriver would be masked by West Point until it was almost abreast the island. Then, most importantly, they saw the most egregious flaw in the planned fortifications. “The fortress is unfortunately commanded by all the grounds about it, and is much exposed to an attack by land; but the most obvious defect is, that the grounds on the West Point are higher than the fortress, behind which point an enemy may land without the least danger. In order to render the pass impassable, it seems necessary that this place should be occupied.”[35] The Congressmen were convinced that Romans did not know what he was doing and recommended in their report that someone with military experience be placed in charge of the project.

In response, the Convention on December 6 appointed yet another committee of three to determine what was happening on Constitution Island. This committee quickly ascertained that the project was a disaster. Work was going much too slowly, Romans’s and the Commissioners’ disagreements had caused the project to be inadequately supervised, and above all the Highlands were still unfortified. Ignoring Congress’ recommendation to fortify West Point, this committee recommended a fort be built on the north side of Popolopen Creek. Just before Christmas these recommendations were sent to Philadelphia.[36]

Romans hurried to New York to try and convince the Convention that his plans were still what were needed in the Highlands. He was successful in persuading the Convention to reverse itself and restart work on Constitution Island as well as build a thirty gun redoubt on the bank of the river opposite West Point. The Convention told him he would then need to try to convince Congress. Then reversing itself, the Convention told the Commissioners to stop work on Constitution Island but gave no further orders on what to do until mid-February. West Point itself was still not going to be fortified.[37]

Washington and Congress had had enough. Romans was paid through February 9, 1776 and dismissed. At that time he had only built an octagonal, wooden blockhouse with eight four-pounders, a barracks, a storehouse, and a wall with fourteen cannons.[38] No one was really in charge that winter on Constitution Island until Washington assumed responsibility for seeing the work completed. He chose Lt. Col. Henry Beekman Livingston to assume command of the project. When Washington became aware of the dismal defenses in the Highlands he dispatched Brig. Gen Lord Stirling to inspect the fortifications. Ironically, in spite of Lord Stirling’s recommendation to fortify West Point, it was neglected again because the summary of Stirling’s letter to Washington made no mention of West Point. As that oversight was being cleared up, the confusion of changing commanders at West Point allowed the recommendation to fall through the cracks. There was still no plan for fortifying West Point by the summer of 1776.[39]

Thus ended the first attempt to deny the Hudson River to the British. It would be another two years before West Point and vicinity was properly fortified. At first glance it’s easy to see why Constitution Island was chosen to be fortified. It appeared that guns placed on the south side of the island should be able to decisively fire on ships sailing upriver. But in fact, positions on West Point and on the east bank of the river actually dominate Constitution Island. Also guns on Constitution Island are at river level and unable to deliver plunging fire into enemy ships. The highest elevation on Constitution Island is 134 feet. On West Point potential battery elevations range from just over 165 feet to almost 400 feet, while on the east bank elevations of around 460 feet are possible. A battery on West Point could easily deliver plunging fire on Constitution Island. West Point also masks the approach of ships sailing upriver from two-thirds of the positions on Constitution Island.[40]

In Romans’ defense, he bought a copy of Military Instructions for Officers Detached in the Field by Roger Stevenson while he was in Philadelphia before going to New York. But this is the only book on military engineering he had. Additionally Romans’s skill with drawings and plans is quite evident in his Fort Constitution sketches. However, instead of building good, basic works that would have defended the Hudson, he spent too much time and money on his “Grand Bastion.”[41] As the Commissioners scathingly informed the Convention concerning Romans’s priorities “there was no necessity of making a temporary work have such an elegant outside appearance, and the inside to be lined with so much nicety and expense.”[42]

Above all, Romans should have been building on West Point instead of Constitution Island, and what he did construct he did not do quickly, properly or economically. Romans’s mistakes led to decisions to fortify downriver at Popolopen Creek which diluted the effort to fix the problem at West Point.[43] Romans’s drive “usually outstripped his talents and his purse—a risky combination.” Additionally “his difficult personality . . . left tension in his wake and generated a widely-held conviction that the engineer lacked the skills required.”[44]

On February 8, 1776 the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania gave Romans command of a company of matrosses, unskilled artillerymen who loaded and swabbed guns and handled ammo, under his original Connecticut rank of captain. Romans’s company left Philadelphia for Canada. Along the way his soldiers were accused of abusing army waggoneers and pillaging from civilians. Romans was court-martialed but the charges were dropped and he was assigned to Fort Ticonderoga and the command of four guns. Not surprisingly, he fell into continuous disputes with his junior officers while there.

Romans resigned from the Army on June 1, 1778 when he was around fifty-eight, quite old for the time. He returned to Wethersfield, Connecticut, and married nineteen year old Elizabeth Whiting. That’s all that history records of Bernard Romans until October 5, 1846 when his eighty-six-year-old widow applied for a Revolutionary War veteran’s and widow’s pension.[45]

In her affidavit she claimed Romans again volunteered for the Army and was enroute by ship to South Carolina. The British captured his ship and sent him to Jamaica as a prisoner of war. He was then sent to some unknown location in the U.S., but he died on the trip, “although from circumstances attending his demise, his friends had good reason to believe him to have been willfully murdered.”[46] She was denied her pension.

In late October 1777 British soldiers, retreating down the Hudson after learning of Burgoyne’s defeat at Saratoga, destroyed the fortifications on Constitution Island. The ruins still stand on Constitution Island today, a testament to the early, unsuccessful efforts to deny the Hudson to the British. They also symbolize how the initial efforts to make the Revolution a success depended on the use of volunteers such as Bernard Romans, who were often not qualified for their responsibilities. Yet in spite of his obvious shortcomings, Romans deserves to be remembered today as an American who was willing to aid his country during the critical early stages of the war.

[1]William Alexander claimed the title of the earldom of Stirling, although he never proved his claim. An able commander, he was honored as an earl by the Continental army.

[2]“To George Washington from Lord Stirling, 1 June 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed September 29, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-04-02-0336. During the Revolutionary period, what we today call West Point was commonly referred to as “the West Point” to distinguish it from better known places on the east bank of the Hudson.

[3]Eugene J. Palka and Francis A. Galgano, Jr., The Historical Military Geography of the Hudson Highlands, 2nd ed. (West Point, NY: U.S. Military Academy, 2006), 33.

[4]“Washington’s Sentiments on a Peace Establishment, 1 May 1783,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed September 29, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-11202.

[5]Palka and Galgano, The Historical Military Geography, 15.

[6]Lincoln Diamant, Bernard Romans: Forgotten Patriot of the American Revolution (Harrison, NY: Harbor Hill Books, 1985), 8-16. Also see “Bernard Romans, Maria Wendell and Colonial Cartography on the Eve of the American Revolution,” New Netherland Connections, accessed December 8, 2019, https://www.americanancestors.org/uploadedfiles/American_Ancestors/Content/Databases/PDFs/NewNetherlandConnections/NewNetherlandConnectionsV.8.pdf. Diamont gives Romans’s birth as c. 1720.”

[11]Edward Mott, Papers Relating to the Expedition to Ticonderoga, April and May, 1775 (Hartford: Connecticut Historical Society, 1860), 169.

[12]Diamont, Bernard Romans, 52-53.

[13]Peter Force, ed., American Archives, 4thSeries (Washington, D.C.: M. St. Clair and Peter Force, 1837-1853), 2:584-585.

[15]Palka and Galgano, The Historical Military Geography, 18.

[16]Dave Richard Palmer, The River and the Rock: The History of Fortress West Point, 1775-1783, 2nd ed. (West Point, NY: Association of Graduates; New York: Hippocrene Books, Inc., 1991), pg. 24.

[17]Force, ed., American Archives, 2:1259, 1265.

[18]Ibid., 2: 1295-1296. Constitution Island was known as Martalear’s Rock until around this time when it was renamed Constitution Island in honor of the British Constitution.

[19]Diamont, Bernard Romans, 69.

[20]Palmer, River and the Rock, 31-32.

[21]“II. Letter Sent, 10–11 July 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed September 29, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-01-02-0047-0003.

[22] Diamont, Bernard Romans, 66-67, 69-70.

[23]Palmer, River and the Rock, 32-33.

[24]Edward C. Boynton, History of West Point, and Its Military Importance During the American Revolution: and the Origin and Progress of the United States Military Academy, 2nd ed. (New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1871), 20-21.

[25] Force, ed., American Archives, 3:736.

[26] Palmer, River and the Rock, 34. The Convention had adjourned on September 2 and turned over control to a Committee of Safety.

[27]Force, ed., American Archives, 3:914-15.

[28]Ibid., 3:917, 919-920, 1268.

[29]Worthington C. Ford, et al., Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789 (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1904-1937), 3:280-282, 485-487.

[30]New York (State), Journals of the Provincial Congress, Provincial Convention, Committee of Safety and Council of Safety of the state of New-York : 1775-1775-1777 (Albany: Thurlow Weed, 1842),1:174.

[31]Force, ed., American Archives, 3:1293-1294.

[32]Palmer, River and the Rock, 40-41.

[33]Force, ed., American Archives, 3:1354-1367.

[34]Ford, et al., Journals, 3:341.

[35]Force, ed., American Archives, 3:1657-1658.

[36]Ibid., 4:387-388, 420-422, 425.

[37]Palmer, River and the Rock, 44.

[38]James M. Johnson, “Staff Rides & The Flawed Works of Fort Constitution,” Engineer, October 1990.

[39]Palmer, River and the Rock, 54, 56-57.

[40]Palka and Galgano, The Historical Military Geography, 22-26.

[41]Johnson, “Staff Rides & The Flawed Works of Fort Constitution.”

[42]Force, ed., American Archives, 3:1360.

[43]Johnson, “Staff Rides & The Flawed Works of Fort Constitution.”

[44]Diamont, Bernard Romans, 8-9.

[46]“Pension Application for Bernard Romans,” Revolutionary War Pensions New York State Applicants, accessed October 30, 2019, http://revwarny.com/romansbernard.pdf.

2 Comments

Dear Mr. Reasor,

Thanks for the great article. I have been puzzling over why my Revolutionary War ancestor Robert Chandler of the 2nd Connecticut Line’s Muster Cards indicate why he spent so much time after the Battle of Monmouth (that he did participate in) at the “Highlands” with his outfit. Critical to my understanding were your sources in particular (4) George Washington’s comments in 1783 calling West Point “the key to America.”

Robert was not apparently in the Battle of Stony Point as he was not in the light infantry until a year following that battle so he and his unit must have had a lot of “on duty” time before and after that battle with the area’s high priority belief held by General Washington.

Thanks for the nice comment, Jeff. I appreciate it. Yes, West Point was an important post during the Revolution. The British were certainly interested in it since this was the post that Benedict Arnold attempted to turn over to them.