The skirmishes at Lexington and Concord are often considered the beginning of the American Revolution, a violent change in the controversy between Great Britain and thirteen of its North American colonies. John Adams opined that the Revolution started many years before: “But what do We mean by the American Revolution? Do We mean the American War? The Revolution was effected before the War commenced. The Revolution was in the Minds and Hearts of the People . . . This produced, in 1760 and 1761, AN AWAKENING and a REVIVAL of American Principles and Feelings, with an Enthusiasm which went on increasing till in 1775 it burst out in open Violence, Hostility and Fury.”[1] Adams felt that the ideological revolution began in 1760-61 but that the war of the Revolution was something different. There were several events that took place in 1774 and 1775 that could have “burst into violence” before muskets were fired on the village green at Lexington.[2] One of these took place in the village of Salem in Massachusetts.

The people of Salem had viewed the differences between the colonies and the Mother Country with foreboding, as noted by a resolution sent by the citizens of the town to the Massachusetts Assembly on October 21, 1765 responding to the Stamp Act: “We the inhabitants of said Salem, being fully convinced that the act lately passed by the Parliament of Great Britain, commonly called the Stamp Act, would if carried into execution be excessively grievous and burthensome to the inhabitants of his Majesty’s loyal province.”[3]

After years of controversial British colonial policies and colonial protests, things came to a head. In a response to the tossing of tea into Boston Harbor on December 16, 1773, Parliament passed a series of acts known as the Coercive Acts. The laws included the closing of the port of Boston, suspension of the Massachusetts’s charter, and a new Quartering Act. Officials who were accused of crimes would be sent outside of the colonies for trial. The colonists referred to these acts as the Intolerable Acts. Gen. Thomas Gage became the governor of Massachusetts with the end of charter rule.

Still, some loyal residents of Salem sent a letter to General Gage after he visited the community on June 4, congratulating him on his appointment: “We, merchants and others, inhabitants of the ancient town of Salem, beg leave to approach your Excellency with our most respectful congratulations on your arrival at this place. We are deeply sensible of his Majesty’s care and affection to this province, in the appointment of a person of your Excellency’s experience, wisdom, and moderation, in these troublesome and difficult times.”[4] The town was divided on the new administration but events continued to occur which led to a confrontation there. In August), an attempt by General Gage to interrupt a Provincial Congress meeting in Salem, followed by the arrest of seven members of the local committee of correspondence, was met by huge crowds of protesters. Gage was forced release the prisoners and his troops left Salem.

Colonials protested the Intolerable Acts in many different ways. In some towns mobs refused to allow basic civic functions. Courts were prevented to meet by crowds of citizens. On September 6, a mob of close to 5,000 people forced officials appointed by the British to resign from their positions.

Colonials and the British army jockeyed for the weapons stored in the colony. Colonials stole cannons and powder from the British around Boston. On September 1, British soldiers seized powder stored on Quarry Hill near Charlestown and took two cannon from Cambridge. The Continental Congress, before it adjourned in October 1774 issued a call for military preparations using terms like “meet with resistance and reprisal,” or “an adequate Opposition be formed.”[5] In December, colonials took arms and ammunition from Fort William and Mary near Portsmouth, New Hampshire. A rash of thefts of arms and ammunition stretched throughout New England.

In February, General Gage received a report from a spy that indicated Salem was a center for assembling military supplies: “Gun carriages making at Salem. Twelve pieces of brass cannon mounted are at Salem and lodged near the North River, on the back of the town . . . there are eight field pieces in an old store, or barn, near the landing place at Salem, they are to be removed in a few days, the seizure of them would greatly disconcert their schemes.”[6] In actuality, nineteen cannon were located in and near the forge on the north side of the North River in Salem, being fitted with carriages. Gage decided to take action, as he had when he sent troops to the magazine atop Quarry Hill. He chose Lt. Col. Alexander Leslie to lead a detachment comprising all the available men of the 64th Regiment, about 250 soldiers.

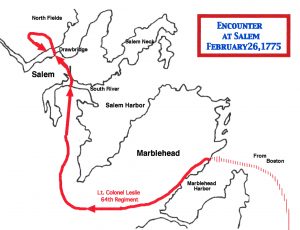

On Saturday, February 25, 1775, the soldiers boarded HMS Lively in darkness with little fanfare. The troops were ordered below decks to make the ship appear as just another warship. They sailed at midnight and arrived in Marblehead Bay just after noon the next day. As it was Sunday, it was thought that the pious people of Marblehead were returning to second religious services at about two that afternoon. The troops would stay hidden in the ship until then.

A few minutes after two o’clock the redcoats poured from the transport, forming up on the dock. They marched quietly through Marblehead and on toward Salem, Leslie on horseback just behind a small advance guard. Very quickly, they realized that their mission was not a secret as messengers raced through the town toward Salem. Bells tolled and instead of being an asset, the church service had gathered people in the town and they poured out to watch the marching soldiers.

Hundreds of locals followed Leslie’s column as it marched through Marblehead. They jostled alongside the redcoats but did not attempt to stop the progress of the men of the 64th Regiment. A local parson, Thomas Barnard, was holding services in the North Meetinghouse, located just shy of the drawbridge over the North River. His congregation disappeared as if by magic when the first call to arms reached them.

Crowds of people gathered along the road from Marblehead to Salem. Briefly delayed by a few planks removed from the bridge at the South Mills, the soldiers quickly replaced the timbers that the colonists had neatly stacked at the end of the structure. Messengers were already en route to nearby communities before the redcoats had reached Salem. The Marblehead and Salem militias were turning out with their weapons as the British soldiers approached the North River and the drawbridge that led to Robert Foster’s forge where the cannons were stored. Unknown to the British, the locals had already moved the cannons to less accessible sites.

Closing in on the river, Leslie could see from a distance that the drawbridge was in the up position, and the apparatus to raise or lower the bridge was on the opposite, north, shore. Dozens of angry colonials thronged around him as the column came to an abrupt stop at the river’s edge. Young men and boys were atop the raised portion of the bridge, shouting insults and curses at His Majesty’s troops.

Leslie ordered the bridge to be lowered, as the colonist’s were blocking the King’s way. They replied that the road was private property and refused to lower the span. A local leader, Capt. John Felt, walked up to Leslie and asked his business. Leslie ignored the man and moved closer to see what was to be done.

A face off resulted as Leslie was unable to convince the citizens to lower the drawbridge. Looking for other options, Leslie noticed several large boats—scows—tied up along the near shore. Quickly, he ordered his men to take possession of the boats. He was too late. Even as the British leader noted the vessels, local owners of the scows and bystanders took action. Captain Felt’s men stove in the bottoms of some of the boats even as owners like Joseph Sprague followed his example. British soldiers were seconds late and unable to take any of the scows before they were rendered unusable. In one of the boats, Joseph Whicher bared his chest to a British soldier’s bayonet and challenged the man to stab him. Whether by accident or intention, the bayonet struck Whicher and produced a small amount of blood. This only encouraged the hecklers surrounding the British soldiers.

The crowds of people surrounding the redcoats were ominous and some taunted them with cries of “Fire!” Leslie and his men showed great discipline as many of the colonists were armed and bands of militia from other towns were joining the mob. Suddenly, Leslie’s patience appeared to be ended and he formed his men to fire. Reverend Barnard engaged in him in a short conversation and the soldiers were ordered to stand down. It was late afternoon and the winter’s shadows crept onto the scene, causing Leslie more consternation. He stated that he would stay until allowed to cross the drawbridge and search the other side for the cannon.[7]

Felt, Barnard, Timothy Pickering of the militia, and Richard Derby, the richest man in Salem, met and discussed their options. The crowd was rowdy, more and more militia from surrounding communities had appeared, and the British soldiers were obviously nervous. How could they avoid a violent clash?

After a few moments of discussion among the colonial leaders, Barnard approached the Lt. Col. Leslie with a compromise. The drawbridge would be lowered if Leslie’s men would conduct a search no more than thirty rods on the other side. British honor would be satisfied, as he would be able to say he conducted the search, and the crowd would be satisfied that nothing was disturbed or damaged. Leslie agreed.

Felt ordered the bridge lowered and Leslie led a small detachment over to the other side. They marched a few rods until they came to a group of about forty militiamen blocking their path. Leslie ordered his troops to turn about and they began the long march back to their ship. Onlookers continued to berate the humiliated recoats all the way back.

Leslie and his men boarded their ship and sailed directly for Boston somewhat embarrassed but without firing into the crowd and starting a war. The spark that ignited the Revolutionary War would have to wait until April 19 at Lexington. The response to the British raid on Salem would lead Gage to be more stealthy on the night march to Concord, but attempts at secrecy would again fail. The colonists would be ready when the grenadiers, light infantry, and Marines marched on the night of April 18.

News reached London of the fiasco at Salem in a little over a month. Edmund Burke told Parliament: “Thus ended their first expedition, without effect and happily without mischief. Enough appeared to show on what a slender thread the peace of the Empire hung, and that the least exertion of military power would certainly bring things to extremities.”[8] The Gentleman’s Magazine proved visionary when it went to print on April 29, 1775: “The Americans have hoisted their standard of liberty at Salem, there is no doubt that the next news will be an account of a bloody engagement between the two armies.”[9] The account was prophetic, as unbeknownst to the anonymous writer, the skirmish at Lexington had taken place a little over a week before.

Note: Paragraph 4 was corrected and updated October 24, 2019, with information provided by a JAR reader.

[1]John Adams to Hezekiah Niles, February 13, 1818, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-6854, accessed April 11, 2019.

[2]For an in depth look at the rebellious activities prior to Lexington and Concord, see Ray Raphael, The First American Revolution: Before Lexington and Concord (New York: New Press, 2002).

[3]Peter Charles Hoffer, Prelude to Revolution: The Salem Gunpowder Raid of 1775 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013), 15.

[4]Loyal citizens of Salem to Thomas Gage, June 11, 1774, ibid, 21-22.

[5]Congress, October 21, 1774, in Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed., Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, Volume 1, 1774 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904), 102, and Congress, October 22, 1774, ibid., 103.

[6]Thomas Gage, Intelligence from unidentified writer, February 24, 1775, in James Duncan Phillips, “Why Colonel Leslie Came to Salem,” Essex Institute Historical Collections Volume XC, October 1954 (Salem: Newcomb & Gauss Co., 1954), 314.

[7]Eric W. Barnes, “All the King’s Horses . . . and All the King’s Men,” American Heritage, October, 1960, 86.

[8]Edmund Burke and Robert S. Rantoul, “Some Claims of Salem on the Notice of the Country. An Address by Robert S. Rantoul,” Essex Institute Historical Collections, Volume XXXII, July-December 1896 (Salem, Essex Institute, 1896), 14.

6 Comments

There is very little information from the 18th century on the Salem incident. Much of it is based on accounts written decades later, and it would be wise to remain skeptical. That Leslie went to Salem is based on evidence of the time, but the story itself is not.

This was a great read. I am an instructor for Project Appleseed and we touch on many of these points during the first of three history presentations covering the events of April 19 1775. It’s very difficult to paint an accurate picture of that day without first providing some context for the hostilities and the overall mindset of the American colonialists at that critical juncture when war broke out.

People who are hearing those stories for the first time need to clearly understand what the social-political climate was like at the time. This article does a great job of summarizing it and providing additional references to explore. Thank you!

Thanks for the note and thanks for the work you do. The Corps’ taught me that marksmanship was important, so keep up the good work!

Excellent read. Thanks Jeff for the research and narrative.

Really well put together article. I had first learned of the Salem Incident from the book “Bunker Hill” by Nathaniel Philbrick, but this article definitely taught me a lot more. The HMS Lively, the warship that Gage used to transport the Redcoats under the command of Colonel Leslie, wasn’t that ship also used to bombard General Warren and the militiamen at the Battle of Bunker Hill as well? All and all an excellent article!

In Charles Endicott’s 1856 “Account of Leslie’s Retreat at the North Bridge in Salem on Sunday, Feb’y 26, 1775” he notes that the troops’ landing occurred at Homan’s Cove “on Marblehead Neck” — on the opposite side of the harbor from the downtown area — which would have made more sense than marching through a crowded town that had a sizeable population at that time, and a militia that had been in training for at least a month. Although a location for “Homan’s Cove” on the Neck is no longer known (just as the locations of other early landmarks etc., including one of several Revolutionary gun batteries, are no longer known), and earlier accounts of the event note that the troops “marched through the town,” it still bears consideration whether the troops did actually march through almost the entire downtown area, or whether they chose an easier, more direct, and more remote approach to Salem, landing on Marblehead Neck and marching from there, as Endicott’s essay suggests (perhaps based on local Marblehead oral history).