Georgia’s fragile independence within the new American republic was shattered on December 29, 1778, when British troops attacked Savannah. Despite clear signs that the British were coming, the capital of the state on that December morning was caught by surprise. Panic set in as the redcoats approached the city. State officials and soldiers fled for the interior in hopes of reestablishing the government up the Savannah River at Augusta. A few weeks earlier, when British vessels neared the Georgia coast, Gov. John Houstoun, fearing an imminent attack on Savannah, ordered twenty-two year-old John Milton, a captain in the Georgia Brigade of the Continental army and the acting secretary of state, to remove the secretary of state’s papers to a safe location. Captain Milton secured the papers and transported them by boat on the Savannah River to Purrysburg, South Carolina.[1]

On January 22, 1779, Milton informed Gen. Benjamin Lincoln, who was organizing an American force at Purrysburg in the hope of recapturing Savannah, that Governor Houstoun had entrusted him with the task of securing the state papers, which he now held in Purrysburg. With the British advancing from Savannah towards Augusta, Milton was worried that the papers “may not be secure so near the Enemy” and asked General Lincoln if the papers “should be removed further into the country.” After receiving approval for the move, Milton transported the papers by wagon to Charleston, South Carolina.[2]

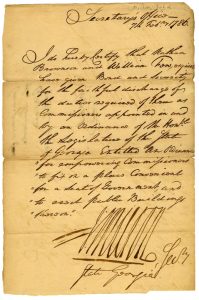

In February 1780, anticipating that a British siege of Charleston would leave the Georgia papers vulnerable to fire, General Lincoln, who was preparing the city’s defenses, ordered Milton to remove the papers north to Moncks Corner, where he could transfer them to the care of a “Mr. Parker, one of the treasurers of this state,” who had the job of protecting the state papers of South Carolina. If Parker refused to take responsibility for the Georgia papers, however, Lincoln authorized Milton to find a secure location for them on his own initiative. That the general deemed the security of the papers to be of vital importance for the future reestablishment of state government in Georgia was apparent by these statements and his willingness to put an army wagon at Milton’s disposal for the transportation of the archives. Lincoln urged Milton to begin his mission without delay—the British under Gen. Sir Henry Clinton were approaching Charleston from the south. He said Milton would be paid for his expenses and “all Quarter Masters and Commissaries are required to give you every assistance you may need in executing this business.”[3]

Milton, who was serving as an aide on Lincoln’s staff, followed the general’s orders. He removed the papers from Charleston, but there is no documentation about his journey from Charleston until his arrival in New Bern, North Carolina, where he left the papers in the care of Gov. Abner Nash. Presumably, he traveled to Moncks Corner as Lincoln had ordered. There is no evidence of any transaction that he may have had with Treasurer Parker. Milton may have remained at Moncks Corner until the British arrived at the town in April 1780. When the British invaded North Carolina in 1781, Milton made his way to New Bern, took charge of the Georgia records, and carted them through Virginia to Annapolis, Maryland, where they remained for the duration of the war. Milton’s documentary odyssey earned him a place in the pantheon of Georgia’s Revolutionary heroes. He became a fixture in the state’s post-Revolutionary administrations in his capacity as secretary of state until he left office in 1799.[4]

The story of John Milton’s Revolutionary exploits became part of Milton family lore, another dramatic chapter in the family history that descendants said could be traced to one of the English language’s greatest poets: John Milton. According to this lineage tale, the family descended from Sir Christopher Milton, the brother of poet John Milton. Unfortunately, extensive scholarship on John Milton the poet refutes the family origin story. There is no evidence that any of the descendants of Christopher Milton settled in the American colonies. What is known is that Georgia’s John Milton was born in North Carolina in 1756. His colonial lineage came from English settlers who moved from Virginia to the Carolinas. Milton’s parents, John and Mary (Farr) Milton, lived in coastal Onslow County, North Carolina. Little is known of their son’s life before 1776.[5]

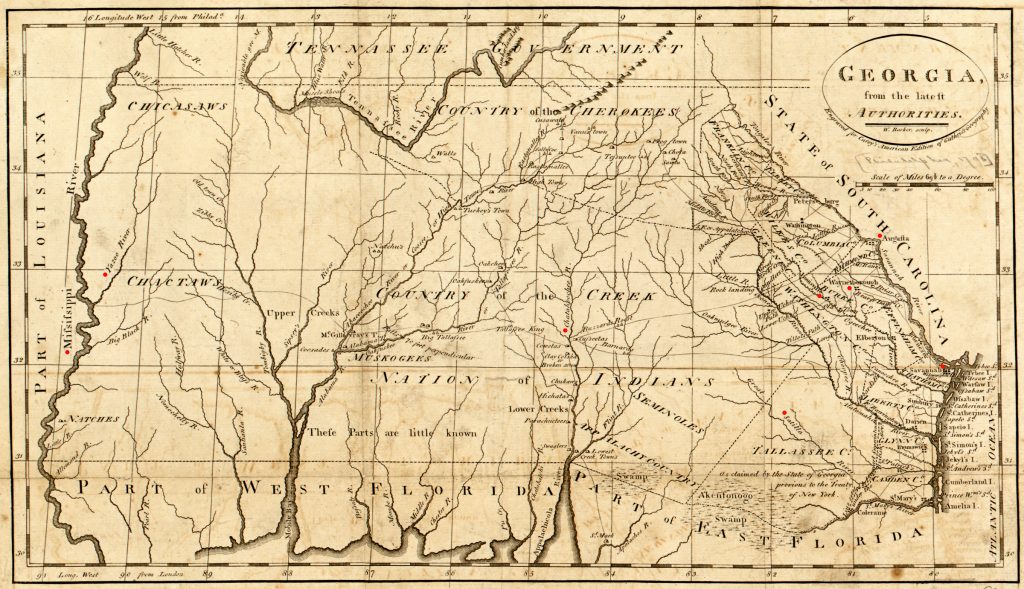

That was the year John Milton began his military service in the American Revolution. In February he joined the Georgia Battalion, the first Continental unit organized in the state. While there is no record of when he moved from North Carolina to Georgia, he may have been drawn to the state by the prospect of cheap land that Georgia secured in the Creek and Cherokee cession of 1773, an act that encouraged a wave of settlers from Virginia and the Carolinas. Milton is listed on the Georgia Battalion’s first return on February 16, 1776, as an ensign in the fourth company of the battalion commanded by Col. Lachlan McIntosh. By the end of April 1776, the battalion reported a strength of 286 men and 27 officers.[6]

The officers reflected the political division among the rebels in Revolutionary Georgia. Before the war, the Whig movement that arose to confront British rule was divided into conservative and radical factions. The conservatives wanted to reform British rule rather than overthrow it. If it came to independence, however, they wanted a government that would maintain their privileged political and economic status. The radicals believed that independence was the only solution in the face of British tyranny. They sought a democratic government for Georgia. Most of the higher officers in the battalion were conservatives, including Milton’s company commander, Capt. Arthur Carney, who eventually switched sides and joined the Tories. Where Milton stood politically at this time is uncertain, but as a young man and recent arrival in Georgia, he was more likely to have supported the radicals over the conservatives. His later service in the field and his tireless efforts to secure Georgia’s state papers were the actions of a committed rebel, not the record of a man who doubted the righteousness of the Patriot cause.[7]

His first encounter with the enemy was not promising. On February 18, 1777, a year after Milton joined the Georgia Battalion, Fort McIntosh on the Satilla River, the southernmost outpost of rebel Georgia, fell to a combined force of Loyalist cavalry and allied Creek Indians. Included among the captured Americans was 1st Lieutenant Milton of the Georgia Battalion. The terms of surrender released the prisoners under oath that they would not take up arms again until formally exchanged for British prisoners. In order to ensure American compliance, the British would hold Lieutenants Milton and William Caldwell hostage until the final exchange occurred. As the Americans marched off, the British, after a rebel force frustrated their further advance in Georgia, withdrew with their hostages south to their base at Saint Augustine in the colony of East Florida. Once arrived, they placed their American guests in Fort St. Mark (the former Spanish Castillo de San Marcos), where they remained until released to return to Georgia in November 1777.[8]

Besides the account of his efforts to save Georgia’s state papers, there is little information about Milton’s service in the war after his return from British captivity. He was commissioned captain in September 1777. In his history of Georgia published between 1811 and 1816, Hugh McCall wrote that after delivering the Georgia records to North Carolina, Milton returned to South Carolina and joined up briefly with the remnants of Lt. Col. William Washington’s dragoons after their defeat outside of Charleston. According to McCall, Milton then joined forces under the command of Baron de Kalb at Hillsborough, North Carolina. McCall next placed Milton at the side of Francis Marion after the American debacle at Camden, South Carolina, in the Swamp Fox’s guerrilla campaign against the British. While it is possible that after the fall of Charleston and the British occupation of his home state, Milton may have volunteered to serve with Marion, McCall may have confused Milton with a “Captain Melton,” a South Carolinian who served under Marion (Milton was often spelled Melton). Even though there are few details about John Milton’s Revolutionary years, his service was distinguished as evidenced by his status as a founding member and first secretary of the Georgia chapter of the Society of the Cincinnati.[9]

His dedication in securing the state papers ensured that the office of secretary of state was his for the asking as the war wound down. In August 1781, with the rebels once again in control of Augusta—the British remained in Savannah—state government was restored with the election of members to the General Assembly. The new government made John Milton secretary of state. He was reelected to the post in January 1783, when the General Assembly convened in Savannah, which the British had evacuated in July 1782. In July 1783, the legislature relocated to Augusta again—Milton became the first mayor in 1792—and the town remained the capital until 1796, when Louisville in newly created Jefferson County became the seat of state government. In November 1797, Milton was elected from Burke County to serve as a delegate to the constitutional convention that met in Louisville to create Georgia’s third constitution in May 1798. He continued to serve as secretary of state until the fall of 1799, when he resigned: Horatio Marbury, Milton’s deputy, became the new secretary. The longevity of Milton’s tenure suggests that the General Assembly saw him as a stable presence during years of tension between Georgia and the United States government over the disposition of Creek Indian lands and the disaster of the Yazoo Land Fraud.[10]

Milton’s prominence in state government made him a logical choice to serve as a delegate to the state convention that met in Augusta to ratify the US Constitution in December 1787 and January 1788. Although he resided in Augusta, located in Richmond County, he was chosen as one of three delegates to represent underpopulated coastal Glynn County (he owned land in Glynn) at the convention. Milton attended every session of the convention and was part of the unanimous vote for ratification. During the nation’s first presidential election in 1789, Milton served as one of Georgia’s five electors. The other electors were George Handley (former governor), George Walton (sitting governor), John King, and Henry Osborne. Georgia’s electors, like all of the presidential electors, each had two votes. All five electors placed their first vote for George Washington but divided their second vote between Milton, who received two votes, and three other candidates: James Armstrong, Edward Telfair, and Benjamin Lincoln.[11]

As a founding member of the Society of the Cincinnati, ratifier of the Constitution, and notable Georgia Revolutionary veteran, Milton had the bona fides of a Federalist in the first term of the Washington administration. There are some clues, however, that Milton, like most Georgia voters of the day, came to support Jeffersonian Republicanism over Hamiltonian Federalism. He remained an opponent of Great Britain, a centerpiece of Jeffersonian foreign policy. In April 1794, Milton served on a committee of prominent residents of Augusta who proposed a number of anti-British resolutions based on what they saw as Britain’s continued anti-American policies on land (arming Indians and retention of forts in the Northwest Territory) and at sea (confiscation of American vessels and impressment of American seamen). The document also included support for revolutionary France, another hallmark of Republicans, when that country was at the height of the Terror: “We view with fraternal sympathy the French nation forcefully struggling with manly fortitude against a host of tyrants.”[12]

The following year, Milton signed off on a document denouncing Jay’s Treaty (named for John Jay, the American negotiator), an agreement designed to resolve issues and relieve tensions existing between Britain and the United States since the American Revolution. Historians Stanley Elkins and Eric McKitrick argued that Jay’s Treaty “was more directly responsible than anything else for the emergence of political parties in America.” Republicans attacked the treaty as a Federalist betrayal of the United States’ alliance with France without any assurances that Britain would respect American neutral rights. While it is true that some prominent Federalists also endorsed the anti-Jay Treaty resolutions—Republicans accused them of doing so solely to garner votes—the fact that Milton was part of the committee designed to prepare the anti-British resolutions in April 1794, including the strong pro-French republican language, adds evidence that he had come to identify with the Republican camp.[13]

Another clue that Milton’s politics followed the Republican rather than the Federalist path was his stance on the Yazoo Land Fraud, the most contentious issue in Georgia politics during the 1790s. The scandal originated in Georgia’s wish to settle and profit from its claim on land extending to the Mississippi River, covering what would become most of the states of Alabama and Mississippi; the federal government contested Georgia’s claims to the area between the Chattahoochee and Mississippi Rivers. In 1795, the legislature voted to transfer most of the Yazoo territory (named for a river in the western section of Georgia’s claim) to four companies for a total of only $500,000. In “an unabashed land-jobbing scheme,” supporters of the sale, “Yazooists,” were enticed by the prospect of vast profits to be made in speculation (wealthy speculators from across the country lined up to invest) on the cheap lands, and bribes circulated through the General Assembly to assure passage of the Yazoo bill that became law in January 1795.[14]

Sen. James Jackson resigned his seat in the US Senate to return to Georgia and a seat in the state House of Representatives, where he led the anti-Yazooist forces who had gained popular support in the wake of the corruption that permeated the land deal. Jackson organized the legislative effort to repeal the Yazoo Act in 1796 and the burning of the bill and associated documents in a public ceremony outside of the capitol in Louisville. Although there is no evidence of Milton’s stance on the Yazoo issue or if he tried to profit in the speculative spree, the fact that he remained in office after the anti-Yazooists had gained control of the legislature strengthens the argument that he sided with the anti-Yazoo camp.[15]

According to historian George R. Lamplugh, the anti-Yazooist James Jackson so dominated the legislature after 1795 as a leader in the House and later as governor (1798–1801) that he “had a virtual veto over state appointments.” Jackson was a diehard Republican who fought against the largely Federalist-led Yazooist forces. It is unlikely that he would have allowed Milton to remain in office if he was pro-Yazoo. On the contrary, according to one source, Jackson even offered Milton the governorship in January 1796, but he declined the office. Jackson’s influence over Milton’s position was apparent in June 1798, when as governor he scolded Milton for witnessing a protest document authored by prominent Yazooist leaders. The document included excerpts from the original Yazoo Act of 1795. Lamplugh contends that as secretary of state, Milton may have agreed to authenticate the excerpts as being from a true copy of the original Yazoo bill as part of his professional duty and not as an act of sympathy with Yazoo. Jackson’s anger over Milton’s action may have led to Milton’s decision to resign his office by the fall of 1799 rather than risk the humiliation of the legislature not reelecting him to the post that year. If Milton was a victim of Yazoo, he had plenty of company. Many lawmakers lost their seats in the legislature as a result of the scandal, and Yazoo “ushered in an era of intense partisanship unprecedented in the post-Revolutionary history of Georgia.” That partisanship, based more on personalities than policies, came to divide Georgia Republicans—Southern Federalism was no longer much of a factor in Georgia politics.[16]

Milton’s identification with Republicanism also extended to a main pillar of that movement’s strength in the South: slavery. According to the first federal census in 1790, Georgia had a total population of 82,548, of whom 29,264 were enslaved persons. During the American Revolution, most enslaved persons fled Georgia during the breakdown of civil authority, and many of them supported the British in hopes of freedom after the conflict. Years after the war ended, there remained armed bands of escaped slaves living among the maroon (fugitive slaves and their descendants) population of coastal Georgia. In January 1787, over four years after the British evacuation of Savannah, Gov. Edward Telfair issued a proclamation, which Secretary Milton endorsed, offering a reward for the apprehension or killing of armed blacks, “run-away Negroe men,” in Chatham and Effingham counties. Escaped slaves resisted the reimposition of bondage in post-Revolutionary Georgia, but by the end of the 1780s the planting class had reestablished the old chattel system.[17]

John Milton, as a member of Georgia’s governing establishment, became a slave-owning planter in due course. Milton’s brother-in-law, former governor John Martin, allowed Milton, who was an executor of Martin’s estate, to choose “a negro boy slave, about the age of five years,” for the future service of Milton’s son Lucius, Martin’s godson. In November 1786, Milton placed an ad in Augusta’s Georgia State Gazettefor the rental of “a PLANTATION within 10 miles of Augusta, that will be sufficient to work from 30 to 40 Negroes.” Whether he found such a plantation is unknown, but he eventually acquired a planation consisting of over 862 acres near Waynesboro in Burke County to the south of Augusta and named it “Padan-aram.” (Milton also had large land holdings in Camden, Glynn, Washington, Franklin, and Richmond counties.) The Bible mentions Padan-aram (“the plain of Aram”) in Genesis as a place where Isaac sent Jacob: “Arise, go to Padanaram, to the house of Bethuel thy mother’s father; and take thee a wife from thence of the daughters of Laban thy mother’s brother. And God Almighty bless thee, and make thee fruitful, and multiply thee, that thou mayest be a multitude of people.”[18] In 1798, Milton owned thirty-seven enslaved persons, making him one of Burke County’s largest slave owners. Those individuals toiled at Padan-aram.

Milton emulated Jacob in producing many children. His wife, Hannah Elizabeth Spencer, was born in 1761 in South Carolina, the daughter of Richard Thomas Spencer and Mary Butler Spencer. Hannah’s sister, Mary Deborah Spencer, was married to former Georgia governor John Martin, who died in 1786. The following year, she married Horatio Marbury, Milton’s deputy secretary of state. The date of John and Hannah’s marriage is unknown, but their first child was born in 1781, so they may have been married in 1780. John and Hannah had eight children. Expecting great things of his sons, Milton gave them the names of literary, military, and political heroes from the classical eras of Greece and Rome and seventeenth century Europe: Homer Virgil Milton, Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Milton, Augustus Caesar Adolphus Gustavus Milton, Fabius Maximus Milton, Algernon Sydney Russell Milton, and Julius Caesar Milton. The Miltons blessed their two daughters with more prosaic names: Mary Anne Armstrong and Anna Maria Milton.[19]

Padan-aram, the site of so many important Milton family events, was also the place of John Milton’s death. He had suffered through health issues, including what may have been osteoarthritis brought on by his long years of writing as secretary of state. In a February 1800 letter to his brother-in-law and former deputy, Secretary of State Horatio Marbury, Milton complained about hand and arm pain: “My family are tolerably well and about, as for myself, I am, I hope, on the mending hand, tho still confined to my room; I have had a sore time of it, my right hand and arm have been more afflicted than ever they were.” On November 14, 1817, the Augusta Herald reported that Milton, age sixty-one, had died on October 19 at Padan-aram and praised him as being “irreproachable” in both his “public and private life.”[20]

By the time of Milton’s death, his son Homer Virgil Milton was a former US Army colonel who had fought bravely in the War of 1812. Homer’s son, John Milton, became governor of Florida during the American Civil War. Besides a large number of descendants, the only physical evidence of the Revolutionary John Milton’s life are the many Georgia state documents that he signed as secretary of state and some official correspondence and personal letters. His name also appears in a number of Georgia newspapers published during his time in office. Milton’s plantation, Padan-aram, is long gone, and his grave on that land is unmarked. In 1857, the Georgia legislature honored Milton’s service to the state by naming a new county after him; however, Milton County, which was located north of Atlanta, was abolished in 1932. Although it would not have occurred to Milton as he rode across the South guarding his state’s documents, those papers became the foundation of the collection that is housed in the Georgia Archives today, a legacy that the poet John Milton would have found worthy of praise. [21]

[1]John Milton to Benjamin Lincoln, January 22, 1779, Benjamin Lincoln Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society (MHS), Boston (Lincoln Papers); Hugh McCall, The History of Georgia: Containing Brief Sketches of the Most Remarkable Events Up to the Present Day (1784) (1811, 1816; reprint, Atlanta: A. B. Caldwell, 1909), 372–374. On Georgia and the American Revolution see Kenneth Coleman, The American Revolution in Georgia 1763–1789 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1958), and Leslie Hall, Land and Allegiance in Revolutionary Georgia (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2002).

[2]Milton to Lincoln, January 22, 1779, Lincoln Papers; On Lincoln, see David B. Mattern, Benjamin Lincoln and the American Revolution (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1998 (paperback), orig. ed., 1995).

[3]Lincoln to Milton, February 25, 1780, File II, Reference Services, RG 4-2-46, Georgia Archives, Digital Collection, File II Names, vault.georgiaarchives.org/digital/collection/FileIINames/id/48585/rec/88, transcribed copy of original letter from Letterbook of Benjamin Lincoln, Boston Public Library.

[4]McCall, History of Georgia, 469. According to Allen Candler, many of the records from the colonial period were lost. Most of the records Milton managed to save were from the secretary of state’s office. See Allen D. Candler, The Colonial Records of the State of Georgia, vol. 1 (Atlanta: Franklin Printing, 1904), 4–5. In March 1784, the state Executive Council authorized Capt. Nathaniel Pearre to bring back the state papers from Maryland; he returned the papers to Milton’s office in Savannah in June 1784. See Allen D. Candler, comp., The Revolutionary Records of the State of Georgia, vol. 2 (Atlanta: Franklin-Turner Company, 1908), 605. Also see “Savannah, in Georgia,” June 10, Charleston South Carolina Weekly Gazette and Public Advertiser, June 19, 1784, 2.

[5]Daisy Parker, “Governor John Milton,” Tallahassee Historical Society Annual, vol. 3, (Tallahassee Historical Society, 1937): 14; John T. Shawcross, The Arms of the Family: The Significance of John Milton’s Relatives and Associates (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2004), 30–33. For an extended exploration of the mythical relationship between the Georgia and Florida Miltons and the poet John Milton see Bruce Boehrer, “Milton in America: The Case of Jackson County, Florida,” Textual Practice, vol. 20, no. 1 (2006): 1–24, accessed April 17, 2019, www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09502360600559746. Harry Roy Merrens, Colonial North Carolina in the Eighteenth Century: A Study in Historical Geography (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1964), 61–63; “Died,” Augusta Herald, November 14, 1817, 3; Zae Hargett Gwynn, Abstracts of the Records of Onslow County North Carolina 1734–1850, vol. 1 (Zae Hargett Gwynn, 1961), 56 and Joseph Parsons Brown, The Commonwealth of Onslow: A History (New Bern, NC: Owen G. Dunn Company, 1960, second printing, 1971), 3–5, 377, 391.

[6]George White, Historical Collections of Georgia (New York: Pudney and Russell Publishers, 1855), 94, 96.

[7]Harvey H. Jackson, Lachlan McIntosh and the Politics of Revolutionary Georgia (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1979), 21–29, 33; White, Historical Collections of Georgia, 94; McCall, History ofGeorgia, 348–49.

[8]Martha Condray Searcy, The Georgia-Florida Contest in the American Revolution, 1776–1778 (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1985), 86–87; McCall, History ofGeorgia, 328.

[9]Francis B. Heitman, comp., Historical Register of the Continental Army During the War of the Revolution, April 1775, to December, 1783 (Washington, DC: W. H. Lowermilk and Company, 1893), 295; White, Historical Collections of Georgia, 113. McCall, History of Georgia, 469. Two Marion historians suggest that “Captain Milton/Melton was a Milton/Melton from South Carolina, not Georgia: Scott D. Aiken, The Swamp Fox: Lessons in Leadership from the Partisan Campaigns of Francis Marion (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2012), 262n10 and author email with John Oller, The Swamp Fox: How Francis Marion Saved the American Revolution (New York: Da Capo Press, 2016). Milton’s part in the Georgia Society of the Cincinnati in Francis Apthorp Foster, comp., Materials Relating to the History of the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Georgia from 1783 to its Dissolution (Society of the Cincinnati, 1934), 2, 9, 53.

[10]Marian B. Holmes, comp. and ed., for Georgia Department of Archives and History, Georgia Official and Statistical Register 1989–90 (Atlanta: Department of Administrative Services, 1993), 208; Charles C. Jones and Salem Dutcher, Memorial History of Augusta, Georgia (Syracuse, NY: D. Mason and Company, 1890), 100, 131; “Augusta, January 14,” Augusta Chronicle and Gazette of the State, January 14, 1792, 2; Yulssus Lynn Holmes, Those Glorious Days: A History of Louisville as Georgia’s Capital, 1796–1807 (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1996), 25–34; “A Proclamation,” Augusta Chronicle and Gazette of the State, August 3, 1799, 4; “Augusta,” Augusta Herald, November 20, 1799, 2; “Burke County,” Augusta Chronicle and Gazette of the State, November 11, 1797, 3; Albert B. Saye, “Journal of the Georgia Constitutional Convention of 1798,” Georgia Historical Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 4 (December 1952); 350–93; Kenneth Coleman, gen. ed., A History of Georgia (Athens: University of Georgia Press, sec. ed., 1991, first ed., 1977), 91–99.

[11]Merrill Jensen, ed., The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution, vol. 3, Ratification of the Constitution by the States, Delaware, New Jersey, Georgia, Connecticut (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin), 267, 269–70, 279; “Augusta, January 10,” Philadelphia Independent Gazetteer, March 17, 1789, 2; “Augusta, May 16,” Augusta Chronicle and Gazette of the State, May 16, 1789, 4.

[12]Lisle A. Rose, Prologue to Democracy: The Federalists in the South 1789–1800 (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1968), 60, 85, 99, 116, 118–19, 132–34, 164–65; “Augusta, April 19,” Augusta Chronicle and Gazette of the State, April 19, 1794, 3.

[13]“Town Meeting,” Augusta Chronicle and Gazette of the State, September 5, 1795, 2; Stanley Elkins and Eric McKitrick, The Age of Federalism: The Early American Republic, 1788–1800 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 415.

[14]George R. Lamplugh, Politics on the Periphery: Factions and Parties in Georgia, 1783–1806 (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1986), 66–72, 104–115; Charles F. Hobson, The Great Yazoo Lands Sale: The Case of Fletcher v. Peck (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2016), 37.

[15]William Omer Foster Sr., James Jackson: Duelist and Militant Statesman 1757–1806 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1960), 105–122; Lamplugh, Politics, 128–38; Hobson, Great Yazoo Lands Sale, 53–54.

[16]Lamplugh, Politics, 136, 147–49, 200—02; Augusta Chronicle and Gazette of the State, July 7, 1798, 4.

[17]Coleman, History of Georgia, 415; Watson W. Jennison, Cultivating Race: The Expansion of Slavery in Georgia, 1750–1860 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2012), 46–53; “A Proclamation,” Augusta Georgia State Gazette or Independent Register, January 13, 1787, 3.

[18]On Martin see James F. Cook, The Governors of Georgia, 3rd and rev. ed. (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2005), 46–49; Ancestry.com, “John Martin Will and Account Papers,” probate date, January 3, 1786, Court of Ordinary, Chatham County, Georgia, Georgia, Wills and Probate Records, 1742–1992(Provo, UT, 2015), images 12–13; Augusta Georgia State Gazette or Independent Register, November 4, 1786, 1; “Offers For Sale,” Columbian Museum and Savannah Advertiser, November 13, 1807,vol. 12, no. 74, p. 3, col. 1; Mary H. Abbe, Georgia Colonial and Headright Plat Index (Atlanta: R. J. Taylor Jr. Foundation and Georgia Archives), 9, 13, 22, 199, 237, 320, 428, 429, Georgia Archives Virtual Vault at vault.georgiaarchives.org, accessed April 16, 2019; number of slaves listed in Burke County Tax Digests, General Tax List by Tax Assessors 1798, p. 20, reel 2622, Georgia Archives County Tax Digest from Microfilm, AH 2622, Georgia Archives Virtual Vault, accessed September 12, 2019, vault.georgiaarchives.org/digital/collection/tax/id/70; “For Sale,” Augusta Chronicle and Gazette of the State,” September 7, 1799, 1; Genesis 28:2 (King James Version).

[19]“John Martin Will and Account Papers,” probate date, January 3, 1786, Court of Ordinary, Chatham County, Georgia, Georgia, Wills and Probate Records, 1742–1992, images 12–13; “Married,” Augusta Georgia State Gazette or Independent Register, January 20, 1787, 3.

[20]John Milton to Horatio Marbury, February 4, 1800, File II Reference Services, RG 4-2-46, Georgia Archives, File II Names Georgia Archives Virtual Vault, accessed April 17, 2019, vault.georgiaarchives.org/digital/collection/FileIINames/id/81126/rec/81; “DIED,” Augusta Herald, November 14, 1817, 3.

[21]“Milton County” in Obediah B. Stevens and Robert F. Wright, Georgia, Historical and Industrial by the Department of Agriculture (Atlanta: Franklin Printing and Publishing, 1901), 761 and Caroline Matheny Dillman, “Milton County,” in New Georgia Encyclopedia (Georgia Humanities and the University of Georgia Press, 2004–2019, accessed April 17, 2019, www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/counties-cities-neighborhoods/milton-county.

3 Comments

Fantastic story! I hope to read more from you. Karen in Canada whose ancestors were from Georgia.

Thanks, Karen. I’m glad you enjoyed the article.

I meant to say in my last email that I find that map of Georgia very interesting. I’m going to try to enlarge it to 24″ x 32 or 36″. I hope it will still be legible. Thank you for sharing.