On Saturday September 17, 1938 New York governor Herbert H. Lehman and 5,000 others assembled in Poughkeepsie to observe the sesquicentennial of the Empire State’s ratification of the U.S. Constitution. One hundred and fifty years previously delegates had gathered in that Hudson Valley hamlet to debate whether New York should ratify that document and thus join the fledgling United States. Delegates haggled and compromised for weeks in the summer heat before reaching a slim majority, which they finally did on July 26, 1788. Ratification had been no sure thing. New York Federalists could count upon only nineteen “yeahs” with certainty when the delegates first gathered that June.[1] After those weeks of tense argument—and numerous preliminary votes against passage—the delegates voted 30-27 in the affirmative, becoming the eleventh state to ratify. One of the thirty “yeahs” was Isaac Roosevelt of New York City, a committed Federalist, prominent sugar merchant, and president of the Bank of New York.

An individual who had originally planned to attend the 1938 commemoration but could not was President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, whose Hyde Park estate was just down the road from Poughkeepsie. President Roosevelt had an appreciation for local, state, and national history, especially as it related to the Roosevelt family, which he regarded more often than not as the same thing. He was especially interested in Dutchess County, where he was born and in which both Poughkeepsie and Hyde Park are located. Like many Roosevelts before him he was a member of the Holland Society. He took the oath of office for both of his gubernatorial and all four of his presidential inaugurals on the Roosevelt 1686 Dutch family Bible.[2] He was also a founding member of the Dutchess County Historical Society, which met at least occasionally at his home, Springwood, overlooking the Hudson River.[3] Incredibly, during his presidency he even served as official historian of the Town of Hyde Park.[4] A lifelong philatelist, President Roosevelt had personally overseen the planning and construction of the Poughkeepsie post office. In October 1937 he spoke “as one of your neighbors” to the gathered locals before laying the cornerstone of the fieldstone structure.[5] As a “neighbor” or otherwise, President Roosevelt spoke that autumn day in the first year of his second term of the controversies between the Federalists and Anti-federalists, of course not failing to mention the role of his ancestor Isaac Roosevelt.

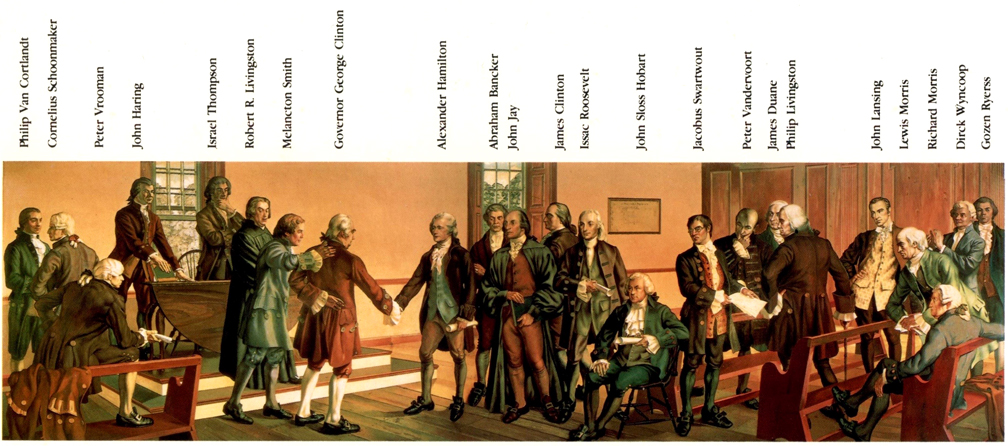

The stately post office remains. Inside are several murals in whose commissioning President Roosevelt had also played a direct role. Financed by the Treasury Department’s Section of Fine Arts, the murals were created under the auspices of the New Deal initiative to put artists and others to work. One of the works in the Poughkeepsie post office is Gerald Sargent Foster’s “Delegates at the New York Convention to Ratify the Federal Constitution” (sometimes called “The Ratification Convention, 1788”). The long list of figures the painting depicts is a Who’s Who of New York in the Early American period. Among those portrayed are George Clinton, Alexander Hamilton, Robert R. Livingston, Melancton Smith, John Jay, Richard Morris, Jacobus Swartwout, Philip Van Cortlandt, Philip Livingston, James Duane, and Isaac Roosevelt. With its sweeping scene of the New York signers having reached agreement and Governor Clinton and Alexander Hamilton sealing the deal with a handshake, Gerald Foster’s painting is reminiscent of John Trumbull’s 1818 masterpiece “Declaration of Independence,” which stands today in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda. Foster’s creation might not be a masterwork on par with Trumbull’s, but it did become part of, if not national iconography, then certainly local and regional prominence. The post office remains a destination for individuals interested in places affiliated with either Franklin D. Roosevelt or New Deal projects. Gerald Sargent Foster’s painting is also testimony to New York’s significance to the Revolution and to Early America. In July 1987 the United States Postal Service in cooperation with the New York State Commission on the Bicentennial of the United States Constitution released a special cancellation commemorative card depicting the striking mural. The Commission also incorporated Foster’s rendering into its official commemorative poster.[6]

Isaac Roosevelt was Franklin’s great-great-grandfather. No person was prouder of his family lineage that Franklin D. Roosevelt, but with the world in crisis such as it was in late summer 1938 there was too much for the president to tend to back in Washington to return to the Hudson Valley for the sesquicentennial of New York’s ratification. Earlier that year Hitler’s Germany had annexed Austria, and was now threatening to overrun Czechoslovakia. British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain had spent the past few days in Berlin speaking to the German chancellor about the crisis while Roosevelt and the rest of the world followed closely. Everywhere one looked tyranny and oppression were on the rise: in Hitler’s Germany, Stalin’s Soviet Union, Mussolini’s Italy, Franco’s Spain, Hirohito’s Japan, and other, smaller nations. Democracy may have looked tenuous but Franklin Roosevelt, ever the optimist, could find the silver lining in most situations. That is in part why the president on that Constitution Day, September 17, 1938, made certain to participate as he could. President Roosevelt addressed the assembled Poughkeepsie crowd via telephone, with five hundred radio stations broadcasting his words nationally. He reminded tense listeners that Washington, Adams, Hamilton, Clinton and their cohort too faced difficult challenges and were even considered traitors by many of their contemporaries. He continued, “Then, as now, there were men and women afraid of the future—distrustful of their own ability to meet changed conditions; short-sighted in their dog-in-the-manger conception of local and national needs. They were afraid of democracy; afraid of the trend toward unity; afraid of Thirteen States becoming one nation.”[7]

Franklin and Isaac Roosevelt’s earliest ancestor in the New World was Claes Martenzen van Rosenvelt. Claes was just one of the many Dutchmen who came to New Netherland in the mid-seventeenth century to test his mettle and make a go of it. Succeeding Roosevelts drew from his inspiration, toiling with little fanfare but great diligence and purpose. They thrived in banking, mercantilism, shipping, and other pursuits, laboring with stolid determination, content in building their interests incrementally. The key to the Roosevelts’ success was their commitment to creating lasting institutions. The Roosevelts however were there to stay, and a surprising number of institutions that Isaac either co-founded or joined soon after their creation still exist in some iteration in the twenty-first century.

During the Stamp Act crisis of 1765-66 New York’s merchants had successfully banded together in response against Parliament’s unpopular taxes. Taking sustenance from their victory and seeing the strength in their numbers, they gathered at Bolton & Sigel’s Tavern (today Fraunces Tavern) on April 5, 1768 and founded an organization dedicated to facilitating trade: The New York Chamber of Commerce. It was the first of its kind in the colonies, which is not surprising given the growing importance of the city and its port.[8] Isaac Roosevelt was one of the earliest members of the organization, in which he would have had a natural interest as a sugar refiner and merchant. It exists today as The Partnership for New York City. In 1770 Roosevelt helped incorporate New York Hospital, which in 1998 merged with Presbyterian Hospital to become New York–Presbyterian. In 1784 with Alexander Hamilton and others he founded the Bank of New York, the city’s first lending institution and today The Bank of New York Mellon. Not least, he helped create New York State and even the United States itself.

Noblesse oblige—doing good while doing well—was very much a family precedent. In the ensuing decades, and even centuries, other Roosevelts founded and co-founded similar institutions relating to public health, culture, banking, and charity within New York City and elsewhere. Chemical Bank (today part of JPMorgan Chase), the American Museum of Natural History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Roosevelt Hospital are but a few examples. Isaac the Patriot—as he later became known—was the first truly prominent Roosevelt, and if not a Founding Father he was certainly part of that milieu. Friends and associates included Alexander Hamilton, John Duane, Richard Morris, John Hancock, Nicholas Low, and John Jay. In 1786 one of Isaac’s daughters married Richard Varick, the Revolutionary War officer who had served under Philip Schuyler before transferring to Benedict Arnold’s command at West Point. After Arnold’s betrayal Varick was held, tried, and eventually acquitted of any involvement. Varick finally became Gen. George Washington’s aide and recording secretary, working on the commander’s papers in, of all places, Poughkeepsie. In civilian life Roosevelt’s son-in-law Varick was, among other things, mayor of New York from 1789, when the federal capital was in Manhattan, until 1801 when he gave way to Edward Livingston. Roosevelts married into the Schuyler, de Peyster, Walton, Barclay, and other families, further mingling their bloodlines into the financial, social, and familial veins of the city and region’s most elite clans.

Isaac Roosevelt’s Colonial New York

Had events not gone as they did and the Patriots not rebelled from George III’s authority, Isaac Roosevelt might be remembered today, if at all, as another industrious merchant who did all right for himself under the British Crown. He was born on December 19, 1726 and grew up on Manhattan’s fashionable Queen Street. The Roosevelts were proud of their lineage. Even though Dutch New Amsterdam had long given way to British New York the Roosevelts made it a practice to remain bilingual, speaking Dutch in the home regularly at Sabbath dinner.[9] They also worshipped in the Dutch Reformed Church, maintaining a sense of community with other families tracing their roots back to Holland. It is unclear if Isaac himself spoke Dutch but his father and uncle both left wills written in that language, which suggests he did.[10] On September 22, 1752 at twenty-five Isaac married Cornelia Hoffman of Kingston, New York. The Hoffmans were another elite clan, owning great swaths of property in Dutchess County that was worked by their African-American slaves. Cornelia was all of eighteen and eventually bore Isaac ten children, some of whom died young in often-pestilential New York. In the ensuing years work, faith, and family remained important as Isaac and Cornelia raised their growing brood. On July 2, 1767 he laid the cornerstone for the North Dutch Church on Fulton Street. The family were members. As chairman of that place of worship’s building committee Isaac must have been proud when the church opened two years later on May 25, 1769.[11] Though converted into a post office in its final years, the church remained part of New York life until finally being torn down in 1875.

Later the same year the North Dutch Church opened, King’s College founded its medical school. Two years later on May 16, 1769 the college graduated its first two medical students in a commencement at nearby Trinity Church. The commencement speaker challenged all the assembled to found a public hospital for the growing city. In 1770 Isaac Roosevelt was one of New York Hospital’s incorporators. The following year, on June 13, 1771, King George III gave the institution his official imprimatur with a charter.[12]

While Roosevelt was doing these things, raising his family, tending his business affairs, and watching the political scene, he and his family were living on Wall Street. In April 1772 they relocated to the home of his recently deceased bachelor brother Jacobus on Queen Street to be closer to his sugar concern.[13] The sugar refinery was a growing enterprise. Directly opposite stood the stately mansion of their new neighbor, the wealthy merchant William Walton.[14]

The Stamp Act had been repealed for some time when the Roosevelts moved to Queen Street but tensions simmered as the British enacted further unpopular legislation. After the Stamp Act came the Townshend Acts with taxes on numerous goods including sugar, the basis of Isaac Roosevelt’s business; the creation of an American Board of Customs to collect the levies on sugar and numerous other commodities such as tea; and a New York Restraining Act designed to punish New Yorkers for failure to comply with the Mutiny (Quartering) Act of 1765. Affairs boiled over in the colonies with the Boston Tea Party in December 1773. The New York General Assembly responded conservatively, hoping that a Committee of Correspondence might navigate a middle course between the British and the colonists. When it did not, New Yorkers responded in May 1774 with an only slightly more assertive Committee of Fifty-One. Taking its legitimacy from the will of the people, the quasi-official Committee of Fifty-One in summer 1774 selected New York’s five delegates to the First Continental Congress under the chairmanship of Isaac Low. Those representatives in turn created the Continental Association, whose local Committees of Inspection were to supervise the colonial boycott of British goods. To accomplish this the conservative Committee of Fifty-One gave way to a more strident Committee of Sixty in November 1774. Many New Yorkers remained primarily Loyalist and conservative, which is not surprising given the strong commercial ties between the city and mother country. The conservative New York General Assembly had even declined to select representatives for a Second Continental Congress in the early months of 1775.

By the time the redcoats and minutemen exchanged shots at Lexington and Concord that April the New York General Assembly’s authority had become tenuous. In New York, as in other colonies, the British were incrementally losing their authority. Though the colonial governor remained nominally in charge, the New York General Assembly itself met for the final time on April 3, 1775. More and more, civilian authorities stepped into the breach. In March an increasingly emboldened Committee of Sixty had called for a meeting of men from various counties to meet at the Exchange in lower Manhattan on April 20, 1775 for the purpose of holding a Provincial Convention and appointing New York delegates to the upcoming Second Continental Congress. The dozens who gathered at the Exchange included Col. Philip Schuyler, John Jay, James Duane, Isaac Roosevelt, Robert R. Livingston, Alexander McDougall, George Clinton, Major Philip Van Cortlandt, and others. Convention participants appointed Philip Livingston their president. Their work done and the delegates to the Second Continental Congress duly selected, the Provincial Convention disbanded on April 22. The following day a horseman arrived in New York City with news of the shots fired in Massachusetts.

Isaac Roosevelt’s Revolutionary War

New Yorkers vented frustration at the British by taking to the streets, seizing munitions, commandeering ships in the harbor, and causing general mayhem. To stanch the growing lawlessness, leaders gathered at the Merchants’ Coffee House on April 29 and signed the “General Association,” agreeing to follow the diktats of the Committee of Sixty, the Provincial Convention, and the Continental Congress in the wake of the General Assembly’s weakening authority.[15] On May 1 the Committee of Sixty gave way to a Committee of One Hundred, one of whose number included Isaac Roosevelt. The Committee of One Hundred was more eager to press grievances than the Committee of Sixty and certainly more than the Committee of Fifty-One. Still it was hardly radical or even revolutionary; for starters its chair was Isaac Low, the conservative merchant who had co-founded the New York Chamber of Commerce in 1768. Isaac Low, unlike this brother Nicholas, would ultimately stay true to the Crown and become a Loyalist. This new organization called for the creation of a New York Provincial Congress, which met in session four times in the succeeding year in response to the growing crisis. The Provincial Congress in effect became New York’s governing body. Isaac Roosevelt was a delegate to each.

Events were moving quickly. The Second Continental Congress created a Continental Army and placed Gen. George Washington in command. On June 25, 1775 New York Royal Governor William Tryon, returning from an extended trip to London, coincidentally arrived in New York City the same day General Washington did. Tryon remained onboard ship until Washington and his entourage passed through the city on their way to Boston. Tyron, that final vestige of colonial authority, remained in the city for many months but eventually fled to the safety of a British ship anchored in New York Harbor in October 1775. Events escalated over the ensuing months until on July 4, 1776 delegates to the Second Continental Congress issued the Declaration of Independence. Five days after that, while New Yorkers were tearing down the statue of King George III on Bowling Green in lower Manhattan, the Provincial Congress declared New York’s independence. The following day the Provincial Congress renamed itself The Convention of Representatives of the State of New York.

Declaring independence does not mean independence is so easily achieved. Gen. William Howe and his forces pushed George Washington and his men out of Long Island and lower Manhattan in the summer of 1776 with little difficulty. The city was the hub of British military operations for the next seven years. During that time it endured two catastrophic fires, and the physical and economic impacts of overcrowding with soldiers and refugees.[16] Isaac Roosevelt and many others thankfully witnessed little of this. He and his family were among those able to flee Manhattan at the war’s outbreak. The Roosevelts spent the next several years north of the city in Dutchess County near Cornelia’s ancestral home in the Patriot stronghold of Kingston. For a time in late 1776 Isaac served in uniform as an enlisted man in Dutchess County’s 6th Militia. Such a position, important though it was, was insufficient for a man of his capacity. Instead, leaders put him in charge of converting £55,000 into paper currency for use within the colonies. It was a complicated task, especially given that there was no standard unit of paper currency within the colonies. He nonetheless managed to perform the feat, converting the British pounds into legal tender.[17] Roosevelt continued his duties a representative for the people of New York. In the Ulster County Courthouse on April 20, 1777—two years to the day after the Provincial Convention at the Exchange—Isaac Roosevelt and other delegates ratified the New York State Constitution. The war continued, with the British military maintaining their control of Manhattan and the Patriots largely holding sway in the remainder of New York. Finally in November 1783 the American Revolution ended.

An Independent New York

When Evacuation Day arrived on November 25, 1783 Isaac Roosevelt was one month shy of his fifty-seventh birthday. He was one of the first to return home, and was not doubt relieved that both his home and his business had survived the fires and the occupation. Soon it would be time to rebuild that city, but first there was to be celebration. Roosevelt hurried to New York City so quickly that he witnessed George Washington’s triumphal return to the city.[18] He was there too at Fraunces Tavern that evening for the party hosted by Gov. George Clinton. People celebrated and gorged for days at numerous affairs. Isaac Roosevelt and others organized a party at Cape’s Tavern at Wall Street and Broadway for Washington and the French allies. Theodore Roosevelt, who like his distant cousin Franklin was something of a historian, in his 1913 autobiography shows Mr. Cape’s bill, on which Isaac signed off as one of the state auditors. The invoice came to just over £156 for expenses including 120 dinners, 135 bottles of “Madira,” thirty “bouls” of punch, and sixty broken wine glasses.[19] Washington said goodbye to his officers at Fraunces Tavern on December 4 and left for Mount Vernon. Then came the harsh reality of building a new nation.

As the calendar turned over into 1784 New York City, just like the United States itself, faced a number of challenges. The city had a number of attributes in its favor, including a deep, natural port with easy access to European and Caribbean markets; open space for settlement in northern Manhattan Island; fertile land farther north easily accessible via the North (Hudson) River; a diverse, multilingual population; mechanics and craftsmen well-skilled in myriad occupations; and a wealthy, educated merchant class accustomed to solving complex social, political, and economic problems. What is more, for all the problems endured during the occupation the experience brought a few, limited benefits. One of them was that the British and Hessians had provided a certain modicum of economic stimulus, spending money, including specie, in the course of their daily presence over seven years.[20] As an added benefit, trade inevitably picked up almost immediately after the British sailed off. Still, the challenges were numerous.

Isaac Roosevelt continued with his business, bringing his offspring James into the operation and renaming the concern Roosevelt & Son. That February he began a new venture that would consume much of his energy in the coming years. An advertisement appeared in the New York Packet on February 23, 1784 inviting interested persons to gather at the Merchants’ Coffee House at 6:00 pm the following evening for the purpose of founding a bank based on “liberal principles.”[21] It is difficult to overstate the novelty—and fear—that banks held for many. Banks were all but unknown to most Americans, who in the wake of the Revolution were inherently nervous of enterprises whose powers were manifest in the hands of a few. There had only been a few banks in the nation’s young existence: the Bank of Pennsylvania, an institution founded in 1780 by Philadelphians for the purpose of aiding the Continental Army; and the more aspiring and powerful Bank of North America, chartered the following year. Now in New York, less than three months removed from Evacuation Day, men were gathering to create a lending institution in Manhattan. On March 15, 1784 organizers gathered again at the Merchants’ Coffee House to elect leaders. At that fateful meeting, bank subscribers elected Gen. Alexander McDougall president and William Seton cashier, with the bank’s activities to be overseen by a board of twelve directors whose numbers included John Vanderbilt, Nicholas Low, Isaac Roosevelt, Comfort Sands, and Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton wrote the Bank of New York’s constitution.[22] The Bank of New York opened its doors on June 9, 1784, directly across the street from Isaac Roosevelt in the front rooms of the Walton House.

In these years just after the Revolution Roosevelt remained active in politics as a member of the New York State Assembly. The year he turned sixty, 1786, was a transformative time in his life. For starters be became president of the Bank of New York on May 8 upon the death of Alexander McDougall. It was relatively simple for Roosevelt to maintain affairs at both the sugar refinery and the bank, the two being adjacent to one another. With James now largely running the refinery, Isaac could confer with his son in the morning, make certain everything was in order, and then tend to bank issues once the lending institution opened at 10:00 am.[23] The same day as his appointment as bank president, daughter Maria married Richard Varick, who at that time was the Recorder of New York City.[24] On November 15, James married Maria Eliza Walton, the niece of William Walton in whose home was headquartered the Bank of New York. These were Franklin D. Roosevelt’s great-grandparents.

These personal and other triumphs aside, things were still difficult for the young United States. Inflation was rampant. The Articles of Confederation were proving insufficient to manage the affairs of the colonies, which were often at odds with one another on trade and other issues. Thus the call in 1787 for a Constitutional Convention that might resolve at least some of the concerns. Whether it was the Convention’s mandate to write an entirely new document is a matter of controversy even today, but nonetheless on September 17 they signed the document in Philadelphia and sent it off to the states for ratification. By the time New York began its ratifying convention on June 17, 1788 eight states had ratified, one less than the number needed to render the Constitution binding. New Hampshire (June 21) and Virginia (June 25) were next to vote “yeah.” Anti-federalists had been concerned about individual liberties, which is why Hamilton, Madison, and John Jay authored The Federalist. In New York men like George Clinton and Melancton Smith were won over slowly until New York ratified the Constitution on July 26.

New York became the first capital of the United States during the Federal period. The government hired Pierre L’Enfant to remodel New York’s City Hall and convert it into Federal Hall. George Washington was sworn in on the balcony overlooking Wall Street on April 30, 1789. Richard Varick, Roosevelt’s son-in-law, because mayor that same year. Still there was personal tragedy. Roosevelt’s beloved wife Cornelia died on November 13. President Washington was invited to attend the funeral but declined. Always worried about precedent, Washington explained in his diary on the 15th that he “Received an Invitation to attend the Funeral of Mrs. Roosevelt (the wife of a Senator of this State) but declined complying with it—first because the propriety of accepting any invitation of this sort appeared very questionable and secondly (though to do it in this instance might not be improper) because it might be difficult to discriminate in cases wch. might thereafter happen.”[25]

Now a widow, Isaac Roosevelt began scaling back. His sugar refinery was in the capable hands of his son James. In these years after the Revolution Roosevelt had increased his wealth by acquiring property confiscated from Loyalists during the war.[26] Financially secure, he retired as Bank of New York president on May 2, 1791. Still he maintained a presence in philanthropic affairs. The year before he had become president of the New York Hospital, which he had helped incorporate twenty years previously. Isaac Roosevelt held that position until his death on October 13, 1794.

Legacy

Isaac Roosevelt was born at a time that led him to be present—and take part in—great events. Still, had his great-great-grandson Franklin Delano Roosevelt not become President of the United States in 1933 Isaac might well have been lost to history. Such would have been inevitable given the milieu in which Isaac lived and worked among the luminaries that were the Founding Fathers. Some physical remnants of Isaac Roosevelt remain today. The Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum in Hyde Park displays the original Gilbert Stuart portrait of Isaac Roosevelt. The New-York Historical Society holds the key to the North Dutch Church tower.[27] The church’s gates now surround part of Columbia University.[28] In April 1937, just a few months prior to President Roosevelt’s address at the corner-laying of the Poughkeepsie post office, his mother Sara lent the Museum of the City of New York a tea set once owned by Isaac and Cornelia for an exhibit entitled “Dining in Old New York.”[29] Thirty years later art and book collector Solton Engel, a 1916 Columbia University graduate, bequeathed to the university several hundred items, including Isaac Roosevelt’s personal copy of the first edition of The Federalist.[30] These artifacts are all reminders of the legacy of an important New Yorker and American. More significant, however, are the vision and accomplishments of the man himself as he worked toward financial success, charity, familial responsibly, and toward the creation of a new nation.

[1]E. Wilder Spaulding, “New York and the Federal Constitution,” New York History20, no. 2 (April 1939): 126.

[2]“Four Presidential Inaugurations,” FDR Presidential Library & Museum, www.fdrlibrary.org/inaugurations, accessed September 14, 2019.

[3]Kevin J. Gallagher, G. C. Dickens, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Robert W. Bingham, “The President as Local Historian: The Letters of F.D.R. to Helen Wilkinson Reynolds,” New York History 64, no. 2 (1983): 136.

[5]“Roosevelt Talk to His Neighbors,” New York Times, October 14, 1937, 12.

[6]Jay Price, Steve McManus, and Ron Morrision. Celebrating Our Constitution: Summary of Selected Programs of State and Local Bicentennial Commissions and Other State Organizations (Washington, D.C.: Commission on the Bicentennial of the United States Constitution, 1987), 45.

[7]Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Radio Message to I50th Anniversary of Constitutional Convention, Poughkeepsie, N Y., September 17, 1938,” Franklin D. Roosevelt—“The Great Communicator” The Master Speech Files 1898, 1910-1945, Series 2, File 1174, Presidential Library & Museum, http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/_resources/images/msf/msf01211, accessed October 3, 2019.

[8]Lee M. Friedman, “The First Chamber of Commerce in the United States,” Bulletin of the Business Historical Society 21, no. 5 (November 1947): 138.

[9]Allen Churchill, The Roosevelts: American Aristocrats (New York: Harper & Row, 1965), 50.

[11]Talbot W. Chambers, The Noon Prayer Meeting of the North Dutch Church, Fulton Street, New York: Its Origin, Character and Progress, with Some of Its Results (New York: Board of Publication of the Reformed Protestant Dutch Church, 1858), 25.

[12]“An Old Hospital in a New Centre,” New York Times, March 31, 1929, 118.

[13]Charles Barney Whittelsey, The Roosevelt Genealogy, 1649-1902 (Hartford: Press of J.B. Burr & Company, 1902), 26.

[14]Karl Schriftgiesser, The Amazing Roosevelt Family: 1613-1942 (New York: Wilfred Funk, Inc., 1942), 110.

[15]Barnet Schecter, The Battle for New York: The City at the Heart of the American Revolution (New York: Walker & Co, 2002), 52-53.

[16]“The North Dutch Church,” Harper’s Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, June 5, 1875, 457.

[17]Churchill, The Roosevelts, 67.

[18]Schriftgiesser, The Amazing Roosevelt Family, 118.

[19]Theodore Roosevelt, Theodore Roosevelt: An Autobiography (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1913), 3.

[20]Henry Williams Domett, A History of the Bank of New York, 1784-1884 (New York: G. P. Putman’s Sons, 1884), 2.

[23]Allan Nevins, History of the Bank of New York and Trust Company, 1784 to 1934 (New York: Privately published, 1934), 27.

[24]Portrait and Biographical Record of Seneca and Schulyer Counties, New York (New York and Chicago: Chapman Publishing Company, 1895), 502.

[25]George Washington, “Washington Papers, November 1789,” National Archives, Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/01-05-02-0005-0003#GEWN-01-05-02-0005-0003-0015-fn-0002-ptr, accessed October 6, 2019.

[26]Harry Beller Yoshpe, The Disposition of Loyalist Estates in the Southern District of the State of New York (New York: Columbia University Press, 1939), 31.

[27]“Key to Tower of North Dutch Church,” New-York Historical Society, https://www.nyhistory.org/exhibit/key-tower-north-dutch-church-0, accessed October 6, 2019.

[28]John Tauranac, “Lost New York, Found in Architecture’s Crannies,” New York Times, February 12, 1999, E44.

[29]“Museum Depicts Old Time Feasting,” New York Times, April 20, 1937, 22.

[30]“Rare Whitman Book among 500 Works Given to Columbia,” New York Times, October 4, 1967, 44.

2 Comments

A very interesting article in all respects. But please do not imply undue parallels or commonalities between those who voted to ratify the Constitution in 1788, with the New Dealers of the 1930s. Many of those who voted in New York to ratify the Constitution did so because of the guarantee that there would be a Bill of Rights added to it, a series of amendments that would limit the power of the federal government. Franklin Roosevelt recognized few if any limits on the power of the federal government that he oversaw.

Thanks for the comment. I don’t think we’re in any disagreement. I aspired less to show that Franklin Roosevelt was a Federalist than to emphasize his family history and that he was proud of such. FDR was clearly a Jeffersonian and not a Hamiltonian. Around the same time of the groundbreaking for the post office and the sesquicentennial of New York’s ratification of the U.S. Constitution he put Thomas Jefferson and Monticello on the nickel. Later he went on to make sure that the Jefferson Memorial got built on the Mall. His Four Freedoms speech of January 1941 clearly alludes to the Bill of Rights in its call for freedoms of speech and worship.

Best, Keith