Thomas Jefferson and Julia Child. Not two people you’d expect to be linked in history. But yet, indeed they are—as two gourmets who loved fine French cuisine. Frequently today in books, magazines, and online articles, Thomas Jefferson is “credited” with “introducing” such French foods as crème brûlée to the American appetite, as well as . . . French fries. Really?

Well, the French fry credit is mostly a myth. But like many things in American history, there’s an even more fascinating story behind the myth. Let’s take a quick look at the historical record of Jefferson, his preference for French foods and how it came about. At face value, it would seem that Jefferson wouldn’t have had much exposure to many exotic foods, living up at Monticello, his home perched atop a mountain overlooking the town of Charlottesville, Virginia. In Jefferson’s time, Charlottesville was practically at the edge of the western Virginia wilderness.

But we also know that Jefferson got around in his life. Aside from Williamsburg, the Virginian colonial capital, he spent vast amounts of time in Philadelphia (a very cosmopolitan city for its time) and other northern cities during the American Revolution and post-Revolution period. He then possibly at least had some small exposure in America to different dishes from foreign cultures like France.

Jefferson and James Hemings in Paris

It was May 1784 and the Revolutionary War was over. The post-war Confederation Congress had recalled John Jay from diplomatic duties in France. It needed to fill the slot of the third Minister Plenipotentiary working in Paris assisting Benjamin Franklin and John Adams. Thomas Jefferson was the logical choice. Congress asked and Jefferson accepted.

On July 5, 1784 Jefferson set sail for England and then to Paris. Sailing with Jefferson was Martha (“Patsy,” his daughter),[1] and a nineteen-year-old enslaved house servant named James Hemings,[2] whom Jefferson referred to in his early records and correspondence as “Jame.” Jefferson’s intent, although he didn’t publicly say so,[3] was to have James master the French “art of cookery”[4] and then bring French recipes and cooking styles back to Monticello when Jefferson’s foreign assignment was up. James Hemings must have shown some culinary promise back at Monticello to have been chosen to accompany Jefferson. Nearly as soon as Jefferson got settled in Paris at his Hôtel d’Orléans[5] on the Rue de Richelieu (before finally settling in at his Hôtel de Langeac residence), he enrolled James in a three-year apprenticeship to learn classic French cuisine. During that period of 1784-1787, Hemings also learned French fluently and was paid 288 livres per year by Jefferson.[6]

By 1787, Hemings was apprenticing for the master chef de cuisine at Château de Chantilly, the country estate of Louis-Joseph de Bourbon (prince de Condé), where sometimes even French kings used to drop in for lunch. And by 1788, Hemings was chef de cuisine for Thomas Jefferson in his Champs-Élysées townhouse and its ever-constant flow of diplomatic guests. No recipes or menus exist from the dinner parties Jefferson hosted. But it’s very likely that, along with Hemings’s learned dishes of crème brulée (“burnt cream”), meringues, French-style crème Chantilly (whipped cream), macaroni and cheese, was a dish served as “pommes de terre frites àcru, en petites tranches”[7] (“potatoes deep-fried while raw, in small cuttings”). In other words—French fried potatoes.

Potatoes (white potatoes in particular, long thought in Europe to have been poisonous), were making a huge mark in French haute cuisine at exactly the same time Jefferson and Hemings were in Paris. “According to legend, the king [Louis XVI] began wearing the plant’s blossoms pinned to his coat, and Marie Antoinette wore a garland of them in her hair. The potato was served at the royal court, which led to the aristocracy to adopt it as well.”[8]

The evening of September 17, 1789 turned out to be the final Hôtel de Langeac dinner party in Paris. The event, which started at 4:00 p.m., was hosted by Jefferson with the planning and execution of the gourmet menu by Hemings. Two of the four visitors included the Marquis de Lafayette and the American Gouverneur Morris. But the talk was of the growing anger and unrest among the commoners of Paris and speculation of whether French soldiers were even still loyal to the monarchy. (We, in the twenty-first century, know that it was the start of the French Revolution.)

Jefferson, being recalled back to America, left Paris on September 25, 1789 with his four charges,[9] a harpsichord, and eighty-six crates of books, wine, seedlings and various kitchen utensils, such as an Italian pasta-making machine. Packed into the shipping containers were also over 150 recipes of collected French dishes—including presumably one for French fries. He was being called back to America to assume the new cabinet position of secretary of state in the new federal government. Hemings accompanied Jefferson to both New York City and Philadelphia as master chef preparing state dishes in his signature “half-Virginian-half-French style.”[10]

By 1793, Jefferson and Hemings had agreed on terms of James Hemings’s requested emancipation: that he would be freed upon completion of a tutorial cooking school at Monticello[11] for chosen kitchen help. Both sides kept their word on the agreement and Hemings was freed in 1796. He settled in Philadelphia and later in Baltimore. As a highly skilled professional, Hemings always found work as a cook.

The Death of James Hemings

A month and a half before newly-elected President of the United States Thomas Jefferson was to take the oath, Jefferson wrote to Baltimore inn keeper William Evans.[12] Evans informally knew Hemings from his Baltimore inn-keeping crowd. Jefferson was working through Evans as a third party to see if Hemings would be interested in the executive chef position at “The President’s House” (the previous name for The White House): “You mentioned to me in conversation here that you sometimes saw my former servant James, & that he made his engagements such as to keep himself always free to come to me. Could I get the favor of you to send for him & to tell him I shall be glad to receive him as soon as he can come to me?”[13]

Privately, however, Jefferson expressed some reluctance to the idea. He had seen through personal observation that as early as 1797 that Hemings had developed a substance abuse problem with alcohol. Jefferson wrote to Evans that Hemings “was an affectionate & honest servant to me . . . and yet the fear of his drinking . . . induces me to wish rather that he would decline the thought.”[14] Regardless, Evans extended the invitation to Hemings as Jefferson wished. But Hemings kept making excuses to not answer back.[15] Evans offered Jefferson his own perceived reason: “as I am rather inclined to believe that, he would not answer your purposes from his being overly fond of liquor.”[16] Three weeks after becoming president in March 1801 and still with no word from Hemings, Jefferson wrote to Evans that, “after having so long rested on the expectation of having him . . . [I] wrote to Philadelphia, where I have been successful in getting a cook equal to my wishes.”

Unfortunately, there was an even more tragic postscript to the James Hemings story. Eight months after taking the presidential oath, Jefferson wrote to Evans asking him to confirm a rumor he had been told that Hemings had, “committed an act of suicide.”[17] Evans replied that unfortunately it was true:

I received your favour of the 1st Instant, and am sorry to inform you that the report respecting James Hennings Having commited an act of Suicide is true. I made every enquiry at the time this melancholy circumstance took place, the result of which was, that he had been delirious for Some days previous to his having commited the act, and it was the General opinion that drinking too freely was the cause.[18]

Historian Annette Gordon-Reed offers her perspective that, “The hectic pace and pressure for perfection drove many chefs to drink, and as the years went by, Hemings himself would fall prey to that professional hazard.”[19]

The Presidential Years

The Philadelphia contact who supplied President Jefferson with “a cook equal to my wishes” was French minister plenipotentiary to America Philippe de Létombe, who had enthusiastically recommended Honoré Julien. Julien worked out so well that he stayed on as Jefferson’s chef at the President’s House through both terms of the presidency.[20]

A story repeatedly told in printed and online accounts tells of a particular dinner party given by Jefferson and Honoré Julien at the President’s House on February 6, 1802. One of the dishes supposedly served at the dinner party was French fries (or “fried potatoes” as they would’ve been called). One of the dinner party guests, Massachusetts congressman Rev. Manassah Cutler, recorded for posterity in his diary the gathering and the food served. The fried foods showing up were “fried eggs” and “fried beef,” but, alas, no fried potatoes:

Feb. 6, Saturday. Dined at the President’s–Messrs. Hillhouse, Foster, and Ross, of the Senate; General Bond, Wadsworth, Woods, Hastings, Tenney, Read, and myself. Dinner not as elegant as when we dined before. Rice soup, round of beef, turkey, mutton, lamb, loin of veal, cutlets of mutton or veal, fried eggs, fried beef, a pie called macaroni, which appeared to be a rich crust filled with the strillions of onions, or shallots, which I took it to be, tasted very strong, and not agreeable. Mr. Lewis told me there were none in it; it was an Italian dish, and what appeared like onions was made of flour and butter, with a particularly strong liquor mixed with them. Ice-cream very good, crust wholly dried, crumbled into thin flakes; a dish somewhat like a pudding—inside white as milk or curd, very porous and light, covered with cream-sauce—very fine. Many other jimcracks, a great variety of fruit, plenty of wines, and good. President social. We drank tea and viewed again the great cheese.[21]

It’s unknown how many times and to whom James Hemings and Honoré Julien served “French fried potatoes” or “pommes de terre frites à cru, en petites tranches” from Hemings’s French recipe. But it must have been a considerable number of times. It’s also quite likely that the dish (because of its simplicity) may have been copied and spread by the multitude of Jeffersonian guests. But there’s no hard documentation on it. “President Jefferson was a culinary superstar in our early republic. He gets credit—probably too much—for introducing some popular European foods into American cuisine. Wealthy households were eager to mimic what the president served on his dinner table.”[22]

But certainly Thomas Jefferson himself didn’t formally “introduce” French fries to the American continent. It’s impossible to trace an exact straight line of fried potatoes (in any shape) directly from Hemings’s French recipe for what would become rectangular American “French fries” in the 1930s. Besides, to complicate things (aside from the fact that both Belgium and France claim to have invented the French fry), the Hemings recipe for “French fries” yields a product looking more like thick, round potato chips.

An Original 1824 Monticello-Related Recipe for “French Fries”

There’s one thing that is clear for historical devotees of French fries. Two years before Jefferson died, Mary Randolph, the sister-in-law to Martha Jefferson Randolph (Jefferson’s daughter living at Monticello) began writing a cookbook from collected recipes. It’s generally accepted that at least some of the Mary Randolph cookbook entries might also contain recipes that James Hemings had brought back from France and taught to Monticello cooks in that 1793-1796 time period. We just don’t know which ones. (To this day, only one sheet still exists[23] in James Hemings’s own handwriting, and that’s a list of Monticello kitchen utensils written just two weeks after Hemings received his freedom.)

Leni Sorensen was Monticello’s “African-American Research Historian and a culinary historian.”[24] Sorensen chimed in on the Jefferson-French-fries controversy a few years ago: “I hope with this final recipe of the year to help lay aside the French Fry/Thomas Jefferson origin myth. Except for not being sliced into what we think of as the long skinny rectangle French fry shape, these round sliced and fried potatoes of Mary Randolph are clearly pretty darn close.”[25]

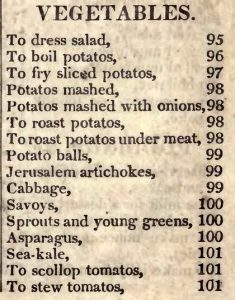

So, to rephrase Sorensen’s expert words, the following Mary Randolph 1824 recipe: “To fry sliced potatos” might get you as close to Thomas Jefferson’s round or curly French fries as you can get today:

Peel large potatoes, slice them about a quarter of an inch thick, or cut them in shavings round and round, as you would peal a lemon; dry them well in a clean cloth, and fry them in lard or dripping. Take care that your fat and frying-pan are quite clean; put it on a quick fire, watch it, and as soon as the lard boils and is still, put in the slices of potatoes, and keep moving them till they are crisp; take them up and lay them to drain on a sieve; send them up with very little salt sprinkled on them.[26]

Vive la liberté and bon appétit!

[1]Martha Wayles Jefferson, Thomas’s wife, had just died on September 6, 1782.

[2]Yes, James’s younger half-sister was Sally Hemings. Sally was staying behind at Monticello at this time. Later, Sally and Thomas’s daughter Polly sailed to Paris in 1787.

[3]“I propose for a particular purpose to carry my servant Jame with me.” Thomas Jefferson to William Short, May 7, 1784,”Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-07-02-0171, accessed April 11, 2019 (Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 7, 2 March 1784 – 25 February 1785, ed. Julian P. Boyd (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953), 229). William Short was Jefferson’s private secretary while in Paris.

[4]Agreement with James Hemings, September 15, 1793, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-27-02-0127, accessed April 11, 2019 (Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 27, 1 September–31 December 1793, ed. John Catanzariti (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 119–120).

[5]The French word “hôtel” previously and still can also refer to a townhouse or even hospital. Jefferson lived in four residences during his five years in Paris, August 1784–September 1789.

[6]Annette Gordon-Reed, The Hemingses of Monticello (New York, W. W. Norton & Company, 2008), 180. Technically James Hemings was nearly a free man the minute he stepped onto French soil under the terms of French law. The law, deemed the “Freedom Principle,” allowed for a slave to be emancipated with few exceptions when a third party in Paris sued for the slave’s freedom.

[7]The full common French phrase for “French fries” or “French fried potatoes.”

[8]Thomas J. Craughwell, Thomas Jefferson’s Crème Brulee: How a Founding Father and his Slave James Hemings Introduced French Cuisine to America (Philadelphia, PA: Quirk Books, 2012), 74.

[9]By 1787, Polly Jefferson and Sally Hemings had also sailed over to Paris to join Patsy Jefferson and James Hemings.

[10]Chef Ashbell McElveen, “James Hemings, Slave and Chef for Thomas Jefferson,” New York Times, February 4, 2016. Chef McElveen, founder of the James Hemings Foundation, characterized a phrase also used by Daniel Webster when he visited Thomas Jefferson at Monticello in December 1824: “Dinner is served in half Virginian, half French style, in good taste and abundance.” D. Webster, E.D. Sanborn, F. Webster, The Private Correspondence of Daniel Webster, Vol. 1 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1857), 365.

[11]The tutorial lessons also made use of the ~150 French recipes collected by Hemings and Jefferson, one of which quite likely was how “To fry sliced potatos” (French fries). Jefferson’s recipe for ice cream, written in his own hand, resides in the Library of Congress.

[12]“William Evans conducted the inn at the sign of the Indian Queen located at 187 Baltimore Street—commonly called Market—the principal street in Baltimore. It was the site of Evans’s tavern and the starting point for both the Philadelphia and southern mail stages (The New Baltimore Directory, and Annual Register; For 1800 and 1801 [Baltimore, 1801], 6, 12, 37).”, Editorial comments by editors – Founders Online, National Archives. Jefferson to William Evans, February 22, 1801,”Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-33-02-0037, accessed April 11, 2019 (Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 33, 17 February–30 April 1801, ed. Barbara B. Oberg (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006), 38-39).

[13]Jefferson to Evans, February 22, 1801, ibid.

[15]“Hemings did not pursue the invitation, perhaps because TJ did not ask him directly.”—Editorial comment by editors – Founders Online, National Archives. Jefferson to Evans, November 1, 1801,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-35-02-0449, accessed April 11, 2019 (Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 35,1 August–30 November 1801, ed. Barbara B. Oberg (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008), 542–543).

[16]Evans to Jefferson, February 27, 1801, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-33-02-0080, accessed April 11, 2019 (Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 33: 91–92).

[17]Jefferson to Evans, November 1, 1801.”

[18]Evans to Jefferson, November 5, 1801,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 11, 2019, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-35-02-0460, (Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 35: 569–570).

[19]Gordon-Reed, The Hemingses of Monticello,227.

[20]Brought from Monticello to assist Chef Honoré Julien in the Jefferson presidential kitchen were: Edith “Edy” Hern Fosset (enslaved cook), Peter Hemings (enslaved cook and brewer), Francis “Fanny” Gillette Hern (enslaved cook), and Ursula (enslaved pastry cook). Adrian Miller, The President’s Kitchen Cabinet: The Story of the African Americans Who Have Fed Our First Families, from the Washingtons to the Obamas (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017), in Forward.

[21]W. P. Cutler and J. P. Cutler, Life, Journals and Correspondence of Rev. Manassah Cutler, LL.D., by his grandchildren William Parker Cutler and Julia Perkins Cutler (Robert Clarke & Co., Cincinnati, 1888), 71-72. The “great cheese” referred to was a giant block of cheddar cheese weighing 1,235 pounds, presented to President Jefferson in January 1802 by the town of Cheshire, Massachusetts, and its 900 cows. It was said, “no Federal cow [a cow owned by a Federalist farmer] be allowed to offer any milk,” lest it should leaven the whole lump with a distasteful savour.’” Obviously by late summer 1803 and with no refrigeration, it was agreed to get rid of the “great cheese.”

[22]Miller, The President’s Kitchen Cabinet, 75.

[23]Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jefflife.html#070; accessed September 10, 2019.

[24]Now owner of Indigo House, “Dr. Sorensen is a PhD expert in 18th- and 19th-century cooking methods used by Virginia housewives and slaves, including those who cooked for Thomas Jefferson.” https://www.heritageharvestfestival.com/speakers/dr-leni-sorensen/accessed September 12, 2019.

[25]The recipe for “Jefferson-era: Fried Potatoes” was published online December 2, 2011 by Leni Sorensen: https://www.monticello.org/site/blog-and-community/posts/jefferson-era-recipe-fried-potatoes; accessed September 10, 2019.

[26]Mrs. Mary Randolph, The Virginia House-Wife or Methodical Cook (F. Thompson, Washington, 1824), 97.

6 Comments

I enjoyed this nifty piece and good research. I can’t help thinking that the second way of slicing potatoes in Mary Randolph’s recipe at the end of the article describes the making of (very curly) potato chips!

Jett, yes, it does! Curly-que french fries have been around longer than I’d ever suspected.

I’m glad you enjoyed the article & thank you for the nice words!

Very interesting article. Is there any source for the first names of the party goers mentioned by Rev. Cutler?

Robert, the identification of the party-goers (including Rev. Cutler of Massachusetts) seems to be all Federalist congressmen: James Hillhouse (CT), Theodore Foster (RI), James Ross (PN), Peleg Wadsworth (MA), Henry Woods (PA), Seth Hastings (MA), Samuel Tenney (MA), and Nathan Reed (MA); which leaves the unknown “General Bond”. He wasn’t even in Boatner’s AmRev encyclopedia and some other sources. Maybe a reader can shed light?

Thank you, this helps to further place these men in the historical context and also to place Wadsworth, Hastings and Tenney in my extended family tree.

Robert – you’re welcome and in that case – congratulations on your extended family tree members!