Aside from Gen. Anthony Wayne’s successful assault upon a British garrison at Stony Point in July, military activity in the first eight months of 1779 had been rather limited. Major Henry Lee, known as Light Horse Harry Lee to future generations, sought to change this in mid-August with a raid upon a British post less than two miles from New York City.

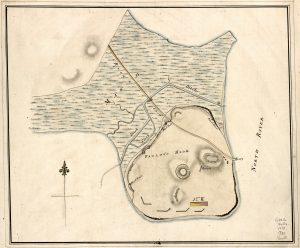

Paulus Hook, or Powles Hook, sat on a peninsula that jutted out from New Jersey into the Hudson River. Although its elevation was barely above sea level, the 400 man garrison at Paulus Hook was protected on three sides by the Hudson River and from the west by a large marsh that flooded at high tide.1 In fact, the only land approach to the fort was over a long causeway through the marsh and over a drawbridge that spanned a tidal moat dug across the peninsula.2 A ring of abattis encircled the post which included two fortified redoubts bristling with cannon and two block houses. All of this was within the shadow of New York City and the British fleet which made Paulus Hook a formidable fort to attack.3

Although General Washington was initially skeptical of Major Lee’s proposal to strike Paulus Hook, Lee was given permission to gather more intelligence on the post in preparation for a possible attack.4 By mid-August 1779, Major Lee had acquired enough information on the garrison and had adjusted his plan of attack sufficiently to gain General Washington’s cautious consent.

Since most of the troops that Lee requested for the operation were to come from Gen. William Alexander, Lord Stirling’s division, Washington wrote to Stirling to solicit his opinion on Lee’s proposal.

I have had in contemplation an attempt to surprise the enemys Post at Powlus Hook and have employed Major Lee to make the necessary previous inquiries. He will inform you of what has passed between us. The number first proposed for the enterprise was 600, but these appeared to me too many to hazard for an object of inferior importance: But by the inclosed letter. . . . Major Lee proposed to reduce the number to 400, three hundred of which to be employed in the attack. As the success must depend on surprise these appear to me sufficient to effect the purpose and as many as ought to be hazarded in the attempt . . . Your Lordship will consult Major Lee fully and if, upon the whole you deem the undertaking eligible you have my consent to carry it into execution . . . .But I need not add that the greatest caution will be necessary not to give a suspicion of our design and to keep it a matter of profound secrecy.The least alarm, would probably occasion disappointment and ruin the party.5

General Stirling approved Lee’s plan, and a week later, on August 18, Major Lee marched southward from Stirling’s headquarters at New Bridge Landing, New Jersey towards Paulus Hook. With him were 350 Virginia and Maryland troops along with a detachment of infantry and another of dragoons from Lee’s corps.6 The dragoons would not participate in the assault, but rather, screen Lee’s detachment along the eighteen mile march route.7

Major Lee tried to time the long march so that his attack commenced at half past midnight, a few hours before high tide, but his guide led the column astray. As a result, Lee and his men spent crucial hours and energy marching through difficult terrain. Lee angrily recalled that,

After filing into the mountains, the timidity or treachery of the principal guide prolonged a short march into a march of three hours; by this means the troops were exceedingly harassed; and, being obliged to pass through deep, mountainous woods to regain our route, some parties of the rear were unfortunately separated.8

Despite the disappearance along the march of a quarter of his detachment, Lee continued on towards Paulus Hook. When they reached the edge of the marsh around 3:30 a.m., Lee sent Lt. Michael Rudolph ahead to reconnoiter the fort. Lieutenant Rudolph reported that the fort was quiet and, despite the approach of high tide, the moat was still fordable.9 With no time to organize his men into three columns as originally planned, Lee ordered them to advance as they were. He explained his decision in a letter to General Washington: “I found my [original plan of attack]impracticable, both from the near approach of day, and the rising of the tide. Not a moment being to spare, I paid no attention to the punctilios of honor or rank, but ordered the troops to advance in their then disposition.”10

Lee pushed his men forward, determined, “to leave my corpse within the enemy’s line,” if the attack failed.11 Capt. Levin Hardy commanded a company of Maryland troops in the assault and described the advance: “We had a morass to pass of upwards two miles, the greatest part of which we were obliged to pass by files, and several canals to ford up to our breast in water. We advanced with bayonets, pans open, cocks fallen, to prevent any fire from our side.”12 Major Lee credited two officers in particular with leading the assault.

The forlorn hopes, led by Lieutenant McCallister . . . and Lieutenant Rudolph, marched on with trailed arms in most profound silence . . . the first notice to the garrison was the forlorn [troops]plunging into the canal. A firing immediately commenced from the block-houses, and along the line of abattis, but did not in the least check the advance of the troops.13

Lee’s men rushed the outer works and stormed into the fort. A bit of fortune shined on them when they discovered that the main gate was open in expectation of the return of a large Tory patrol. This also meant that the garrison was weaker than anticipated. The Americans poured into the fort, but they still had two strong redoubts and two fortified block houses to overcome.

Lieutenant McAllister, supported by Maj. John Clark of Virginia, easily overwhelmed the dazed defenders of the center redoubt, capturing six cannon and the post’s colors.14 At the same time, Lieutenant Rudolph, supported by Capt. Robert Forsyth and Capt. Allen McLane, stormed one of the blockhouses.15 The main barracks of the post, filled with invalids and camp followers, also fell quickly, but the fort’s commander, Maj. Nicholas Sutherland and about twenty-five Hessians successfully defended the last redoubt.16

Up to this point the Americans had not fired their muskets, relying instead on surprise and their bayonets to subdue the enemy. With one of the redoubts still in enemy hands, musket fire might have been useful. It was not an option for most of Lee’s troops, however, because most of the men ruined their powder when they waded through the flooded marsh and moat. The Americans gathered what little powder they could from the fallen and captured enemy and tried to seize the garrison’s powder magazine but failed to gain access to it.

With over 150 prisoners and approximately 50 enemy killed or wounded, all at the expense of only a handful of his own men, Lee could confidently claim success, despite the continued resistance of one of the enemy redoubts. To preserve this victory, however, Lee and his detachment, along with their prisoners, had to make good their return to the American lines.17 With alarm guns firing across the Hudson River and the British army rousing itself in New York, it was imperative that Lee begin his return march immediately. He recalled that, “[t]he appearance of daylight, my apprehension lest some accident might have befallen the boats [that Lee and the prisoners were to march to]the numerous difficulties of the retreat, the harassed state of the troops, and the destruction of all our ammunition by passing the canal conspired in influencing me to retire at the moment of victory.”18

Major Lee ended the assault on the remaining enemy redoubt and ordered his detachment to march westward with their prisoners, sparing the fort’s barracks from destruction because it was occupied by women and children and sick soldiers.19 Lee also failed to spike the enemy cannon. There was just no more time left.

To reduce the chance of being intercepted by a large enemy force from New York, Major Lee followed a different route westward for the return march, one that required the detachment to cross the nearby Hackensack River by boat. Unfortunately, while on the march to the boats, Lee learned that Capt. Henry Peyton’s cavalry detail, tasked with guarding the boats, never received word of Lee’s delay and had departed with the boats at sunrise, assuming that Lee had cancelled the attack.20 With no way across the Hackensack River, Lee was forced to retrace his march northward along his original route and risk interception by the enemy. He recalled,

In this very critical situation, I lost no time in my decision, but ordered the troops to regain Bergen road . . . . Oppressed by every possible misfortune, at the head of troops worn down by a rapid march of thirty miles, through mountains, swamps, and deep morasses, without the least refreshment during the whole march, ammunition destroyed, encumbered with prisoners, and a retreat of fourteen miles to make good, on a route admissible of interception at several points . . . one [enemy] party moving in our rear and another . . . in all probability well advanced on our right, a retreat naturally impossible to our left, under all these distressing circumstances, my sole dependence was in the persevering gallantry of the officers, and obstinate courage of the troops.21

Once again, fortune shined on Lee and his men when they encountered a detachment of fifty Virginians (likely part of Lee’s missing men) with dry gunpowder.22 Lee halted long enough to distribute a few cartridges to each man and then continued on. When they reached the vicinity of Fort Lee they were met by another large body of troops, reinforcements sent by General Stirling. Lee’s men could now effectively defend themselves, which is what they did when an enemy detachment suddenly emerged on their flank. After a brief skirmish, the Americans pushed on to New Bridge and safety.

Major Lee’s detachment reached camp around 1:00 p.m., exhausted from nearly twenty-four hours of constant activity. They had marched almost twenty miles under difficult conditions to surprise the enemy at Paulus Hook. At the loss of just a handful of men, they captured over 150 enemy troops and killed or wounded another 50.23 They then marched another twenty miles past an alarmed enemy, burdened with enemy prisoners that they guarded with virtually empty muskets.

Praise for Lee and his expedition was extensive. Gen. Nathanael Greene informed his wife that, “Major Lee has performed a most gallant affair . . . This expedition is thought to be more gallant than the Stoney Point.”24 Fellow Virginian, Gen. George Weedon, diplomatically noted that, “Wayne’s and Lee’s enterprises add great luster to our arms and do those Gentlemen much honor.”25

General Wayne was not bothered by the comparisons to his successful attack of Stony Point and graciously congratulated Major Lee.26 Someone else who was thrilled by Lee’s success was the commander-in-chief, General Washington. He expressed his gratitude to Lee and his men in the general orders.

The General has the pleasure to inform the army that on the night of the 18th instant, Major Lee at the head of a party composed of his own Corps, and detachments from the Virginia and Maryland lines, surprised the Garrison of Powles Hook and brought off a considerable number of Prisoners with very little loss on our side. The Enterprise was executed with a distinguished degree of Address, Activity and Bravery and does great honor to Major Lee and to all the officers and men under his command, who are requested to accept the General’s warmest thanks.27

Praise for Lee came also from Washington’s staff. Alexander Hamilton observed to his fellow aide, John Laurens, that, “Lee unfolds himself more and more to be an officer of great capacity.”28 Hamilton also hinted at a possible character flaw in Lee when he added, “if he had not a little spice of the Julius Caesar or Cromwell in him, he would be a very clever fellow.”29

Perhaps it was this spice of Caesar and Cromwell that upset a small group of officers who withheld praise for Lee and instead directed accusations of wrongdoing at him. The first hints of disgruntlement arose from General Stirling, who seemed bothered with the degree of praise lavished on Lee instead of himself. Stirling questioned the legitimacy of placing Major Lee, a cavalry officer, in command of what was primarily an infantry detachment. Gen. William Woodford and Gen. Peter Muhlenberg, both fellow Virginians, chimed in with a complaint that Lee was not the senior officer in the detachment and that he should have relinquished command to Maj. John Clark.

General Washington tried to quell the objections with a long letter to Stirling. In it Washington dismissed the notion that cavalry officers had no right to command infantry detachments or that a major was unqualified to command a force the size of Lee’s detachment (400 men plus Lee’s cavalry).30 Washington then outlined why Major Lee was the best choice to command the expedition.

This officer’s situation made it most convenient to employ him to make the necessary previous inquiries. It was the best calculated to answer the purpose without giving suspicion. He executed the trust with great address intelligence and industry and made himself perfectly master of the post with all its approaches and appendages. After having taken so much pains personally, to ascertain facts and having from a series of observations and inquiries arranged in his mind every circumstance on which the under-taking must turn, no officer could be more proper for conducting it.31

If General Washington thought his letter would halt the dissent, he was mistaken. Although General Stirling wisely let the matter drop, Generals Woodford and Muhlenberg, perhaps at the behest of some of their subordinate officers, pushed for a court martial of Lee. The young major was stung. It especially bothered him that his own countrymen (fellow Virginians) were behind the accusations. Major Lee shared his troubles with his friend, Joseph Reed, President of Pennsylvania’s Supreme Executive Council: “Generals and Colonels are now barking at me with open mouth. Colonel Gist, of Virginia, an Indian hunter, has formed a cabal. I mean to take the matter very serious, because a full explanation will recoil on my foes, and give new light to the enterprise.”32

Lee confessed that he had actually been too generous in his praise for some of the troops in the attack. “I did not tell the world that near one half of my countrymen (fellow Virginians) left me—that it was reported to me by Major Clarke as I was entering the marsh,—that notwithstanding this and every other dumb sign, I pushed on to the attack.”33

Lee asserted that he was prepared to sacrifice his life in the attempt on Paulus Hook while the efforts of many of Major Clark’s Virginians were, “not the most vigorous.” Lee ended the letter by assuring Reed that

I am determined to push Colonel Gist and party. The brave and generous throughout the whole army support me warmly. . . . I have received the thanks of General Washington in the most flattering terms, and the congratulations of General Greene [and] Wayne. Do not let any whispers affect you, my dear sir. Be assured that the more full the scrutiny, the more honour your friend will receive and the more ignominy will be the fate of my foes.34

Major Lee faced eight charges at his court martial. They came down to the following accusations:

- Withholding information from Colonel Gist.

- Lying about the date of his commission to keep command of the detachment from Major Clarke (who actually outranked Lee).

- Conducting the detachment in a disorderly manner.

- Appointing an officer to serve under a more junior officer.

- Appointing an officer to command the forlorn hope instead of choosing the commander by ballot.

- Retreating too soon, before taking more prisoners and destroying more stores.

- Conducting a disorderly retreat.

- Behaving in a manner unbecoming an officer.35

Lee’s friends and allies were confident that Lee would prevail on all counts. Gen. Nathanael Greene wrote a telling letter to Gen. George Weedon of Virginia at the beginning of the court martial expressing his confidence in Lee’s acquittal.

Major Lees gallant attack upon Powleys Hook I suppose you have heard of. This stroke is not of such magnitude as the Stony Point affair; but the difficulties were much greater, from the situation of the place, and the strength of the post. The attack was conducted with great spirit, and fortune favor’d it with success. The obstacles were so numerous that had not Major Lee been one of her favorite Children he must have faild. However he succeeded to the great joy of his friends. But can you believe it, he has been persecuted with a bitterness by his Countrymen, that is almost disgraceful to mention. . . . He has been arrested, and brought to trial, for misconduct, but there is not a shadow of evidence against him- on the contrary the more the matter is enquird into, the better he appears. After passing through the furnace of affliction, he will come out, like gold seven times tried in the fire.36

General Washington clearly wished the issue to be settled in Lee’s favor and provided evidence in the form of a letter to discredit the charge that Lee’s retreat was too hasty.

My principal fear, from the moment I conceived a design against the post, was on account of the difficulty of the retreat, founded on the relative situation of the post to that of the Enemy of York Island. This circumstance induced me to add . . . that no time should be lost in case [the attack] succeeded, in attempting to bring off Cannon, Stores or any other article, as a few minutes delay might expose the party . . . to imminent risk. I further recollect that I likewise said that no time should be spent in such case in collecting Stragglers of the Garrison, who might skulk and hide themselves, lest it should prove fatal.37

Even Major Clark (who was denied the honor of command because Lee allegedly lied about the date of his commission) helped Major Lee by testifying on his behalf.38 After five days of testimony the court rendered its decision. Describing some of the charges against Lee as “unsupported” and “groundless,” and some of his actions as necessary and fully justified, the tribunal acquitted Major Lee with honor on all eight charges.39 Their summation of the last charge was telling of the whole trial.

The Court . . . are of opinion that Major Lee’s conduct was uniform and regular, supporting his military character with magnanimity and judgment and that he by no means acted derogatory to the Gentlemen and the Soldier which characters he fills with honor to his country and the Army.40

Two weeks after the verdict, Congress expressed its high regard for Major Lee’s actions at Paulus Hook by passing the following resolution.

Resolved, That the thanks of Congress be given to Major Lee, for the remarkable prudence, address, and bravery displayed by him on the [late enterprise against Paulus Hook.]41

Congress also expressed their approval of Lee’s treatment of the prisoners captured in the raid noting that he displayed, “humanity in circumstances prompting to severity.”42 This was a reference to the fact that Major Lee gave quarter to the enemy (accepted their surrender) during the attack, something the British neglected to do on a similar type of raid that they conducted against Col. George Baylor’s dragoons a year earlier.

Along with these resolutions of approval, Congress considered a promotion for Major Lee, but this was tabled.43 Instead, Congress directed that a gold medal be struck and presented to Major Lee to commemorate his bold attack on Paulus Hook.44

Although it took years for the medal to be designed and cast, the fact that Major Lee was awarded one of only eight such medals in the whole war must have taken some of the sting out of his court martial. His future exploits in the service of General Nathanael Greene’s southern army in 1781 also insured that his court martial would be but an asterisk to his service in the Revolutionary War.

1John W. Hartmann, The American Partisan: Henry Lee and the Struggle for Independence, 1776-1780 (Shippensburg, PA: Burd Street Press, 2000), 106-107.

4John C. Fitzgerald, ed., “General Washington to Major Henry Lee, 28 July, 1779,”The Writings of George Washington, Vol. 15 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1936), 498.

5John C. Fitzgerald, ed., “General Washington to Lord Stirling, 12 August, 1779,” The Writings of George Washington, Vol. 16 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1937), 83-84.

6Frank Moore, ed., “Extract of a letter from an officer at Paramus,” Diary of the American Revolution, Vol. 2 (New York: Charles T. Evans, 1863), 207.

7Hartmann, The American Partisan, 109.

8Moore, “Extract of a letter from an officer at Paramus,” 207.

11William B. Reed, “Henry Lee to President Reed, 27 August, 1779,” Life and Correspondence of Joseph Reed, Vol. 2 (Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1847), 126-27.

12Reed, “Levin Handy to George Handy, 22 July, 1779,” Life and Correspondence of Joseph Reed, 2: 126.

13Moore, “Extract of a letter from an officer at Paramus,” 207-208.

14Hartmann, The American Partisan, 114.

15Mark M. Boatner III, ed., Encyclopedia of American History (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1966), 839.

16Hartmann, The American Partisan, 114-115.

17Reed, “Levin Handy to George Handy, 22 July, 1779,” Life and Correspondence of Joseph Reed, 2: 126.

18Moore, ed., “Extract of a letter from an officer at Paramus,” 208.

23Reed, “Levin Handy to George Handy, 22 July, 1779,” Life and Correspondence of Joseph Reed, 2: 126.

24Richard K. Showman, ed., “General Greene to Catherine Greene, 23 August, 1779,” The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, Vol. 4, (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina, 1987), 333.

25Showman, ed., “General Weedon to General Greene, 20 September, 1779,” The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, 4: 401.

26Anthony Wayne to Henry Lee, Jr., August 24, 1779, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

27Fitzgerald, ed., “General Orders, 22 August, 1779,” The Writings of George Washington, 16: 149.

28Harold Stryatt, ed., “Alexander Hamilton to John Laurens, 11 September, 1779,” The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, Vol. 2, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1962), 168.

30Fitzgerald, ed., “General Washington to General Stirling, 28 August 1779,” The Writings of George Washington, 16: 190-194.

32Reed, “Henry Lee to President Reed, 27 August, 1779,” Life and Correspondence of Joseph Reed, 2: 126.

35Fitzgerald, ed., “General Orders, 11 September, 1779,” The Writings of George Washington, 16: 262-265.

36Showman, ed., “General Greene to General Weedon, 6 September, 1779,” The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, 4: 364.

37Fitzgerald, ed., “General Washington to Major Henry Lee, 1 September, 1779,” The Writings of George Washington, 16: 217-218.

38Hartmann, The American Partisan, 123.

39Fitzgerald, ed., “General Orders, 11 September, 1779,” The Writings of George Washington, 16: 62-265.

41Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed., “24 September, 1779,” Journals of the Continental Congress, Vol. 15, (Washington, D.C. : Government Printing Officer, 1909), 1099-1100.

3 Comments

Thanks for an informative article on this aspect of Paulus Hook. I only learned of this event when researching an ancestor in Gist’s Supplemental Regiment. Did General Weedon in fact refer to him as “the head of the Wrongheads”?

Thank you for a fascinating article, Michael, with an excellent narrative pace. A couple of questions about the medallion, which appears to be a bronze (or bronzed?) version of the presentation one (I’m assuming the one depicted isn’t a re-strike.) Did Congress authorize multiple copies, and how were they distributed? Is Lee’s gold medal still extant? And who were the other seven recipients?

Rand, while not answering all of your questions, see Gary Shattuck’s JAR article on the gold medal recipients.

https://allthingsliberty.com/2015/04/7-gold-medals-of-americas-revolutionary-congress/