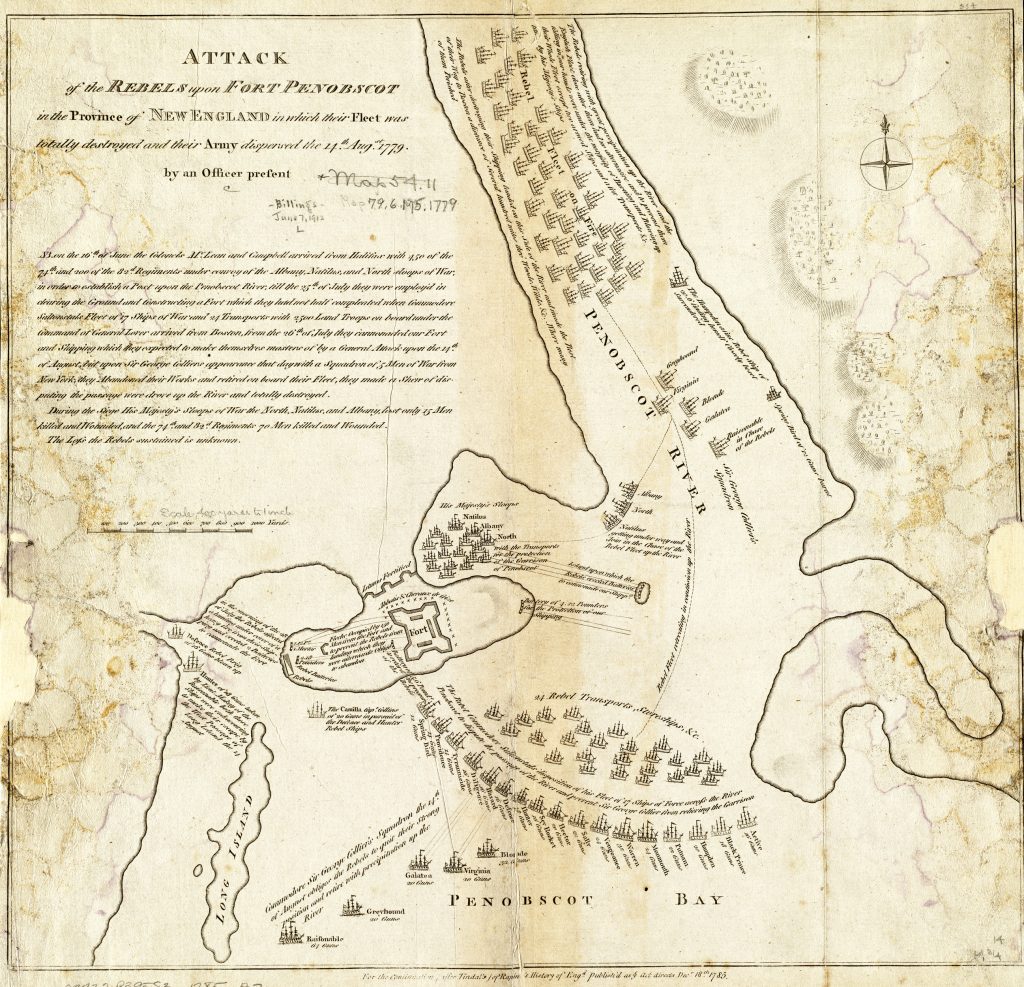

For much of the Revolutionary War, the relative obscurity and isolation of the three Massachusetts counties of York, Cumberland, and Lincoln along the coast of present day Maine protected the inhabitants from British threats. This changed in June 1779, when Gen. Francis McLean and 700 British troops, escorted by a handful of British warships and transports, landed on a peninsula near the entrance to Penobscot Bay (about mid-way up the coast of Maine).1 General McLean’s arrival was part of an effort to start a new British province, New Ireland, which was to extend from the Penobscot River eastward up the coast to the St. Croix River. British leaders believed that the presence of a strong British post on Penobscot Bay would help hasten the establishment of New Ireland and isolate and neutralize the small settlement of Machias (which had been a nuisance to the British in Nova Scotia).

McLean’s force landed in mid-June and immediately built a fort upon high ground overlooking Penobscot Bay and the mouth of Bagaduce River (which flowed south and east of the peninsula). Much of the peninsula was heavily wooded and the western shore, which overlooked the bay, rose steeply to one hundred feet above the sea, making an attack from that direction very difficult. Three British warships under Capt. Henry Mowat blocked the entrance of the river and protected the southern and eastern approaches to the British fort (dubbed Fort George by General McLean) while the narrow northern approach, which was bordered by a marsh and water, was covered by the fort’s guns.

News of the British arrival in Penobscot Bay reached Boston within a week and the Massachusetts state government reacted decisively by authorizing a military expedition to drive them away. Fifteen hundred troops from the counties of York (300 men), Cumberland (600 men), and Lincoln (600 men) were summoned, and a large fleet of ships, including the thirty-two-gun continental frigate Warren, was organized into an expeditionary force.2 Command of the ground forces went to Gen. Solomon Lovell of Weymouth. Lovell, whose military experience stretched back to the French and Indian War, had led a brigade of Massachusetts militia at Rhode Island in 1778. Lovell’s second in command, Gen. Peleg Wadsworth, had also seen action in Rhode Island.

The expedition’s ground troops were divided into three militia regiments. Unfortunately, all three regiments failed to recruit their allotted quotas so the expedition began almost 500 men short of its goal.3 Furthermore, the quality of the recruits was questionable. General Peleg Wadsworth noted that “One fourth part of the Troops . . . appear’d to be Small Boys & old men, & unfit for the service.”4 Regardless of these concerns, the expedition’s leaders pushed forward and prepared to sail to Penobscot Bay. Col. Samuel McCobb commanded the militia troops from Lincoln County while Col. Jonathan Mitchell led the Cumberland County troops and Maj. Daniel Littlefield did the same for the York County troops. About one hundred artillerists under Lt. Col. Paul Revere and over two hundred marines onboard the warships rounded out the available ground troops which amounted to approximately 1150 men.5

The troops were transported and protected by a large fleet of twenty-one transport ships and eighteen warships.6 The warships included Continental and Massachusetts state naval vessels as well as a number of privateers outfitted for combat. Commodore Dudley Saltonstall of the Continental Navy commanded the fleet. The total number of cannon distributed among his warships numbered nearly 300 and ranged from a few 18 and 12 pound guns aboard the Warren to numerous 4, 6, and 9 pound guns aboard the rest of the warships.7

The ships and men of the expedition rendezvoused at Boothbay Harbor in mid-July and set sail for Penobscot Bay on July 24. Saltonstall’s fleet entered the bay the next day, and a few of his ships traded cannon fire with Captain Mowat’s ships, but the exchange had little effect on either side.

General Lovell attempted to land some of his troops near Dice’s Point, along the high bluffs on the west side of the peninsula, but recalled his men before they landed because of poor weather conditions. A second attempt to land troops early the next morning was repulsed by a small British force atop the bluffs. The Americans redirected their attention to Nautilus Island where a British artillery battery helped Captain Mowat cover the mouth of the Bagaduce River. The British battery was manned by forty British sailors who fled in the face of a large detachment of American marines. The captured British cannon were repositioned by a detachment of Lieutenant Colonel Revere’s artillerists, so that they could fire on Captain Mowat’s ships. This forced Mowat to withdraw his ships further up the Bagaduce River and made it impossible for Mowat to cover the western shore of the peninsula with his cannon.8

While all of this occurred, General Lovell’s militia made a third attempt to land on the western shore, but the death of Major Littlefield of York County ended this effort. Littlefield and two of his men drowned in the assault when a British cannonball sunk their boat before it reached the shore. Thirty-six hours later, early in the morning of July 28, Lovell launched a fourth and final assault on Dice’s Point. General Wadsworth recounted the dawn landing years later:

The morning was quite still but somewhat Foggy. The Vessels of War were drawn up in a Line just out of reach of Musket Shot & 400 Men (viz. 200 of Militia & 200 Marines) were in Boats along side ready to push for the Shore on Signals. The highest Clift was preferred by the commander of the Party, knowing that his men would make the best shift in rough ground. The fire of the Enemy opened upon us from the top of the Bank or Clift, just as the boats reached the Shore. We step’d out & the boats immediately sent back. There was now a stream of fire over our heads from the Fleet & a shower of Musketry in our faces from the Top of the Cliff. We soon found the Clift unsurmountable even without Opponents. The party therefore, was divided into three parts, one sent to the right, another to the left till they should find the Clift practicable & the Center keeping up their fire to amuse the Enemy. Both parties succeeded & gained the Height, but closing in upon the Enemy in the Rear rather too soon gave them opportunity to escape, which they did, leaving 30 kill’d, wounded & prisoners. The conflict was short, but sharp, for we left 100, out of 400, on the shore & bank. The marines suffer’d most, by forcing their way up a foot Path leading up the Clift. This Action lasted but 20 Minutes.9

Capt. John Welsh commanded the marines who scaled the cliff one shrub or branch at a time. He was fatally wounded in the assault, but his marines reached the top. Another account of the assault from an unknown American participant proudly boasted of the courage displayed by the troops:

Landed our troops under a shower of cannon and musquet balls, some loss on both sides—never did men behave with so much courage—They jumped ashore, stood three fires from [the enemy] then drove them into their fort.10

General Lovell was also proud of his men and recorded the following in his diary:

When I returned to the Shore it struck me with admiration to see what a Precipice we had ascended, not being able to take so scrutinous a view of it in time of Battle, it is at least where we landed three hundred feet high, [actually closer to 100 feet] and almost perpendicular & the men were obliged to pull themselves up by the twigs & trees.11

British resistance to the assault was surprisingly weak in part because General McLean never believed that the main American attack would come from the west. McLean assumed that all of the previous American activity along the western shore (which he considered impossible to ascend) was really a feint to distract the British from the main assault somewhere else on the peninsula. As a result, he posted only a small picket guard of about eighty men along the bluff. Lt. John Moore commanded part of this picket guard and described the American attack:

After a very sharp cannonade from the shipping upon the wood, to the great surprise of General M’Lean and the garrison, they effected a landing. I happened to be upon picket that morning, under command of a captain of the 74th regiment, who, after giving them one fire, instead of encouraging his men (who naturally had been a little startled by the cannonade) to do their duty, ordered them to retreat, leaving me and about twenty men to shift for ourselves. After standing for some time I was obliged to retreat to the fort, having five or six of my own men killed and several wounded. I was lucky to escape untouched.12

Moore and his surviving men joined the rest of the British picket force in a hasty retreat to Fort George and the garrison braced for a full scale assault. Based on the size of the American fleet, General McLean believed the Americans vastly outnumbered him and reportedly commented, “I was in no situation to defend myself, I only meant to give [the Americans] one or two guns, so as not to be called a coward, and then have struck my colors, which I stood for some time to do, as I did not wish to throw away the lives of my men for nothing.”13

McLean avoided the humiliation of surrender when the expected American attack never materialized. After the successful landing onshore, General Lovell became cautious and entrenched his army about 600 yards from Fort George. Lovell informed the Massachusetts Council of his actions soon after the landing:

This morning I have made my landing good on the S.W. head of the Peninsula which is one hundred feet high and almost perpendicular very thickly covered with Brush & trees, the men ascended the Precipice with alacrity and after a very smart conflict we put them to the rout, they left in the Woods a number killed & wounded & we took a few Prisoners. Our loss is about thirty kill’d & wounded, we are within 100 Rod of the Enemy’s main fort on a Commanding piece of Ground, & hope soon to have the Satisfaction of informing you of Capturing the whole Army.14

While General Lovell and the Massachusetts ground forces settled into a siege of Fort George, Commodore Saltonstall displayed some aggressiveness by leading three of his warships, including the thirty-two gun continental frigate Warren, against Captain Mowat’s ships. As they entered the mouth of the Bagaduce River, Saltonstall’s vessels were pounded by British cannon in the fort and along the shore, and by Mowat’s ships. The American ships inflicted only minimal damage on Mowat’s vessels and withdrew badly battered.15 Despite this setback, Commodore Saltonstall remained determined to capture or destroy Captain Mowat’s ships and moved to neutralize one of the British shore batteries on the peninsula that had damaged his ships.

The Half Moon battery was a strong British outpost on the southwestern shore of the peninsula. Its purpose was to help Captain Mowat defend the mouth of the Bagaduce River and prevent the Americans from sailing into the river to attack Fort George from the south and east. A detachment of Commodore Saltonstall’s marines and sailors, supported by some of Col. Samuel McCobb’s militia, attacked the battery early in the morning of August 1. The militia performed poorly and fled in the face of British resistance, but the marines and sailors overwhelmed the garrison and seized the position before daybreak. Unfortunately for the Americans, a British counterattack at dawn dislodged the marines and sailors and returned the Half Moon battery to British hands. Commodore Saltonstall, discouraged by this setback, changed tactics and began a siege upon Mowat’s ships by placing naval cannon on the mainland to bombard the British ships.

An uneasy stalemate ensued over the next two weeks as the Americans slowly extended their trench line and batteries closer to Fort George and the British ships. General Wadsworth recalled, “We were employed daily, or rather Nightly in advancing upon their Fort by Zigzag intrenchments till within a fair gunshot of their Fort so that a man seldom shew his Head above their Works.”16

By August 13, anxiety among the American commanders about the possible arrival of a British relief force finally convinced General Lovell and Commodore Saltonstall to launch a joint attack on the British fort and ships. The Americans were about to proceed with a direct assault on both when several large vessels were sighted entering Penobscot Bay. The American commanders feared that the approaching vessels were British warships with reinforcements and cancelled their attack. When their fears were confirmed, Lovell and Saltonstall ended the siege and evacuated their men. Lovell’s troops and almost all of their gear and supplies were quietly loaded aboard transport ships under cover of darkness.17 By morning the American transport ships were struggling to sail upriver, away from the British threat.

Saltonstall’s warships followed Lovell’s transports and were pursued by the British. To the shock of Lovell and his men on the transports, instead of standing to fight the British navy and protect the transports, Saltonstall’s warships caught up to and then passed the transport ships. Many of the transport captains panicked and guided their slow ships towards the western shore of the Penobscot River. One by one they beached and burned their vessels rather than let the troops and sailors fall into British hands. Most of the transports were aground and on fire before nightfall, scattered along the western shore of the river below present day Bucksport.18 The Americans aboard the doomed ships scrambled ashore, leaving most of their gear and supplies behind. Fortunately for these men, the British were more interested in the armed American ships and continued their pursuit upriver. The stranded Americans on the western shore of the Penobscot River were left to make their way westward through the Maine wilderness to the Kennebec River. Behind them burned the wreckage of over half the American fleet. The American ships still afloat struggled further upstream.

Some made it to the falls of Bangor where General Lovell proposed that a fortified position along the shore be built to protect them, but the captains and crews disagreed and chose to burn their vessels and flee westward.19 The demise of the Penobscot Expedition was a significant military and financial blow to Massachusetts. Hundreds of men were lost and the state was nearly bankrupted by the cost.20 The reputations of Paul Revere, Dudley Saltonstall, and Solomon Lovell, along with all of the troops associated with the expedition, were tarnished. Criticism of the sailors and troops, especially the marines, was largely undeserved. The men of the Penobscot Expedition had been hastily assembled and poorly led, and yet they had nearly defeated a well entrenched force of British regulars. Had Commodore Saltonstall and General Lovell been more decisive in their actions, the entire affair may have ended differently. Alas, bad luck and bad leadership caused the Penobscot Expedition to end disastrously.

1John Calef, “Journal of the Siege of Penobscot,” The Magazine of History with Notes and Queries, No. 11, (New York : William Abbatt, 1910), 303.

2Nathan Goold, “Colonel Jonathan Mitchell’s Cumberland County Regiment, Bagaduce Expedition, 1779,” Collections of the Maine Historical Society, Series 2, Vol. 10, 54.

3C.B. Kevitt, “General Lovell Journal, July 21, 1779,” General Solomon Lovell and the Penobscot Expedition: 1779, (Weymouth, MA: Weymouth Historical Commission, 1976), 29.

4James Phinney Baxter ed., “Statement of General Wadsworth,” Documentary History of the State of Maine, Vol. 17, (Maine Historical Society, 1913), 273.

5George E. Buker, The Penobscot Expedition: Commodore Saltonstall and the Massachusetts Conspiracy of 1779.(Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2002), 41.

6Buker, The Penobscot Expedition,29-31.

8Calef, “Journal of the Siege of Penobscot,” The Magazine of History with Notes and Queries, No. 11, 307.

9“General Peleg Wadsworth to William D. Williamson,” Collections of the Maine Historical Society, Series 2, Vol. 2, 157-158.

10Buker, The Penobscot Expedition, 44.

11Kevitt, “General Lovell Journal, July 28, 1779,” General Solomon Lovell and the Penobscot Expedition: 1779,35.

12Joseph Williamson, “Lieutenant Moore to his father, Sir John Moore at Castine During the Revolution,” Collectionsof the Maine Historical Society, series 2, Vol. 2, 408.

13Buker, The Penobscot Expedition, 45.

14Kevitt, “General Lovell to Jeremiah Powell, 28 July, 1779,” 80-81.

15Calef, “Journal of the Siege of Penobscot,” The Magazine of History with Notes and Queries, No. 11, 308-309.

16Nathan Goold, “Peleg Wadsworth to William D. Williamson, January 1, 1828, Colonel Jonathan Mitchell’s Cumberland County Regiment: Bagaduce Expedition, 1779,” Collections of the Maine Historical Society, Vol. 10, 71.

17Kevitt, “General Lovell Journal, August 13-14, 1779,” General Solomon Lovell and the Penobscot Expedition: 1779,48, 50.

18Kevitt, “General Lovell Journal, August 14, 1779,” General Solomon Lovell and the Penobscot Expedition: 1779, 50.

19Buker,The Penobscot Expedition,90-91.

20Mark M. Boatner, Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (New York : D. McKay Co., 1966), 852.

3 Comments

It is always a pleasure to read anything written regarding the Penobscot Expedition. I have been a student of the expedition for 20+ years and have twice visited the site. Mike’s article is a solid introduction to what happened, but there is much more intrigue and personality conflicts that are wholly unknown to the vast Rev War community. Paul Revere’s reputation suffers as a result of his actions at Bagaduce. Perhaps the battle is overlooked because it can be considered a State (Massachusetts) rather than a Continental operation, even though Continental Marines and a few Continental warships were involved. The disaster has been considered the worst defeat of American Naval forces until Pearl Harbor.

I was just reading about the Penobscot Expedition last week because my 5th great-grandfather was in Col. Henry Jackson’s Regiment who was recalled from Rhode Island and sent by way of Boston to reinforce the expedition. While they were near the Isle of Shoals, they heard about the disaster and instead put in at Kittery to help gather the stranded men.

“The Fort,” by Bernard Cornwell is a great historical novel about this expedition. It gives a great about of detail and remains an easy read. You may be very surprised about Paul Revere’s behavior. I would suggest anyone studying this event get a map with the place names as they were in 1779.