In a country in which one of the main constitutional principles is separation of church and state, it is counter-intuitive to find that there are chaplains for the two houses of Congress. Aside from a couple of unsuccessful court challenges, the position has managed to survive into modern times largely due to custom and tradition. This tradition, which dates to the First Continental Congress in 1774, did not start well. Jacob Duché was appointed as chaplain, at least unofficially, for purposes of providing an opening prayer. As Duché strode to the lectern on September 7, 1774, to deliver a rousing prayer in support of the revolutionary cause, few could foresee the twists and turns his life would take, most prominently a national furor over his brief correspondence with Gen. George Washington.

The motion to employ Duché, an Anglican Rector, to address the opening of the Continental Congress was made by Samuel Adams of Massachusetts. John Jay of New York and John Rutledge of South Carolina opposed it, because “we were so divided in religious Sentiments, some Episcopalians, some Quakers, some Aanabaptists, some Presbyterians and some Congregationalists, so that We could not join in the same Act of Worship.”[1] Adams, defending his proposal, said Congress could “hear a Prayer from a Gentleman of Piety and Virtue, who was at the same Time a Friend to his Country,” that he had heard that Mr. Duchè “deserved that Character,” and “that Duchè . . . might be desired, to read Prayers to the Congress” at their opening the next day.[2] The motion passed.

The New Englander Adams, no fan of the Anglican church, had a strategic motive. Having an Anglican rector deliver the prayer would hopefully encourage more Anglicans to support the cause and demonstrate to the British that support for the rebel position was more widespread than they thought. He made sure that his friend Joseph Warren in Boston publicized the address there.

Adams would later defend his choice of Duché, stating that “as many of our warmest friends are members of the Church of England, [I] thought it prudent, as well on that as on some other accounts, to move that the service should be performed by a clergyman of that denomination.” Delegate Joseph Reed pronounced the appointment of Duché (and the prayer service itself) to be not only a needed spiritual support for the fledgling country, but a “masterly stroke of policy.”[3]

Duché delivered a fiery prayer to open Congress, starting with the 35th Psalm and, to the surprise of many, adding extemporaneous remarks. The reaction was outstanding. John Adams observed that “the service stirred warm patriotic feeling in those present,” and that it generally “had an excellent effect upon everybody here”[4] Silas Deane went further, stating that Duché “prayed with such fervency, purity, and sublimity of style and sentiment . . . that even Quakers shed tears.”[5]

Who was this Anglican who made such an impression? Duché, born in 1738, was part of the initial graduating class of the College of Philadelphia in 1757. One of his seven classmates was Francis Hopkinson, a future signer of the Declaration of Independence whose sister, Elizabeth, Duché would marry in 1760. Subsequent to his graduation he made two trips to England seeking ordination in the Church of England, which he gained in March 1759. He taught oratory after further study at Cambridge University and was ordained a deacon. He entered the priesthood in 1762 and succeeded Richard Peters in 1775 as rector of the United Parishes of Christ Church and St. Peter’s in Philadelphia.[6]

Psalm 35 “was very appropriate for the political climate of the time and became a unifying moment for the men present. Because this Psalm deals with David’s appeals to the righteous God for help against his enemies that have punished and persecuted him, many colonists found it symbolic of political conflict they were facing.”[7] It proclaims, “Let them [David’s enemies] be as chaff before the wind: and let the angel of the Lord chase them” (verse 5). Verse 20 states “For they speak not peace: but they devise deceitful matters against them that are quiet in the land.” The parallels to the current struggle were unmistakable.

Duché went on to deliver an extemporaneous prayer to supplement the Bible verse, praying that God “on these our American States, who have fled to Thee from the rod of the oppressor and thrown themselves on Thy gracious protection, desiring to be henceforth dependent only on Thee,” and that He “convince them of the unrighteousness of their Cause and if they persist in their sanguinary purposes, of own unerring justice, sounding in their hearts, constrain them to drop the weapons of war from their unnerved hands in the day of battle!”[8]

Duché had performed a heroic service to the Congress—uniting them when they needed it the most, laying the foundation for the later accomplishments of the American Congress, and in the process becoming the one of the first national heroes of the American Revolution.[9] His eloquence pushed Duché, entirely without his having sought it, into the political spotlight[10], a spotlight that would prove to be too hot and too bright for him to handle.

He continued to preach and inspire the rebel cause, encouraging them to “‘Stand Fast’ as the guardians of liberty,” in a published sermon called “The Duty of Standing Fast in Our Spiritual and Temporal Liberties” (July 1775) and two weeks later, he published a sermon called “The American Vine” which decreed a general fast throughout the colonies.

In July 1776, independence was declared. Less than a week later, John Hancock asked Duché to be the official chaplain of the first Congress. His acceptance was in retrospect the beginning of the end, setting off a series of events which rapidly spiraled out of control. For Duché, though he didn’t have it clear in his mind, independence was a bridge too far. He certainly supported the colonies in their dispute with the mother country, but his thinking wasn’t yet crystallized on independence. He accepted the chaplaincy almost reflexively.

At first, it looked like he was fully committed after independence was declared. Duché and vestry members at Christ Church in Philadelphia responded to the Declaration with warm support, agreeing to “omit those petitions in the Liturgy wherein the King of Great Britain is prayed for.” By doing so, Duché went expressly against the oath he had made when ordained in the Church of England.[11] This seemed to affirm his dedication to the cause. Instead, three months after the Declaration, he suddenly resigned his chaplaincy post, due to claimed health issues and a desire to tend to more local duties. He claimed to remain devoted to the rebel cause, but the resignation was a bad portent for what was to come. He would later call his acceptance of the chaplaincy of the post-Declaration Congress a mistake, and given ensuing events few could argue.

In September 1777, the British took Philadelphia. Duché opted to remain in the city, a risky choice given his prior actions, despite his more recent resignation, as he saw it his duty to continue to support his parishioners. Allowed to preach, though with British soldiers included in the congregation, he reverted to praying for the King. Nevertheless, he was subsequently arrested. And while his imprisonment lasted but one night, as one historian put it, he “left his patriotism in his cell.”[12]

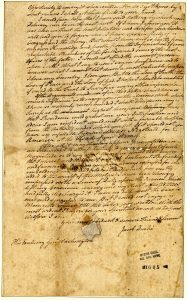

On October 8, 1777 he committed the act that would complete his patriotic reversal in a most stunning way. He penned a letter to George Washington, begging him to end the war and capitulate to the British. To take his appeal right to Washington was not out of the blue in that he had known Washington as an acquaintance, if not a close friend, for over twenty years. It is difficult to ascertain the extent of their familiarity, as only about half a dozen letters passed between them. Calling on this relationship, he begged Washington to keep the letter private. Washington could not and would not. According the poet and loyalist Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson who delivered the letter, Washington paced while reading it, showing a great deal of agitation. Finally, while acknowledging his esteem for both Fergusson and Duché, he stated that he had been placed in a position of trust by the American people and that “the proposal of Mr. Duchey, though conceived with the best intention, is not framed in wisdom.”[13]

Washington felt duty-bound to send the letter to Congress, writing to Hancock that “I received a Letter of a very curious and extraordinary nature from Mr Duché, which I have thought proper to transmit to Congress. To this ridiculous—illiberal performance, I made a short reply, by desiring the bearer of it [Fergusson], if she should hereafter by any accident meet with Mr Duché, to tell him, I should have returned it unopened.”[14] Soon thereafter it was published throughout the colonies to the same audiences who had read his stirring pro-rebel sermons. Instantly, Duché was transformed in the public eye from a hero to a traitor.

Asking Washington to abandon the cause was bad enough, but the way he framed his case made popular reaction even worse. In the letter, which ran over 3,000 words, he asked Washington if the conflict was worth “resign[ing] everything that was dear to you. You abandoned all those Sweets of domestic life, of which your affluent fortune gave you an uninterrupted enjoyment.” He demeaned the acts of the leaders of the revolution as “A Degeneracy of Representation—confusion of councils—Blunders without number. The most respectable characters have withdrawn themselves and are succeeded by a great majority of illiberal & violent men.” Putting undoubtedly too fine a point on it, he went on to tell Washington, “Are the Dregs of a Congress, then, still to influence a mind like yours? These are not the Men you engaged to serve. These are not the Men that America has chosen to represent her.”[15]

He belittled the colonies for their lack of resources (there was truth in this) and held out as a chimera the possibility of French entry into the war to help the Americans. He went on to take to the United States Navy to task: “Turn to your little Navy—Of that little, what left? Of the Delaware fleet, part are taken, the rest must soon surrender. Of those in the other Provinces, some taken, one or two at Sea, and others lying unmanned, and unrigged in their harbours. And now, where are your Resources? O my dear Sir! How sadly have you been abused by a faction void of truth, & void of tenderness to you & your Country? They have amused you with Hopes of a Declaration of War on the Part of France.”[16] Duché’s statement could not have been more ill-timed, as it was around the same time Congress received news of the victory at Saratoga, the pivotal event that would facilitate French support. Overall, he painted an extremely apocalyptic picture to the general: “your harbours are blocked up, your cities fall one after another, fortress after fortress, battle after battle is lost. A British army, after having passed almost unmolested thro’ a vast Extent of Country, have possessed themselves with ease of the Capital of America. How unequal the Contest now! How fruitless the expense of Blood!” Duché then put forth a plan of surrender and negotiation.[17]

Duché even pulled out what he might have thought was his trump card, an appeal to Washington’s vaunted sense of honor and duty, writing, “your character will rise in the Estimation of the virtuous and noble; it will appear with lustre in the Annals of History, and form a glorious Contrast to that of those, who have sought to obtain Conquests & gratify their own Ambition by the destruction of their Species and the Ruin of their Country.” Lastly, he believed as a man of religion that he was obligated to try to stop the bloodshed, concluding by saying, “I could not enjoy a Moment’s Peace, ‘till this Letter was written. With the most ardent Prayers for your spiritual as well as temporal Welfare”[18]

As if to drive the final spike in his doom, Duché had the temerity to dun His Excellency for an answer. Five days later, he followed up his initial letter with a short note asking for a response, and in a mastery of understatement: “My mind will remain in a state of painful anxiety, ‘till I have your candid answer and ‘till I am assured under your own hand, that I have not thereby forfeited your esteem, and that you are not in the least offended at the freedom with which I have written. By this lady you will have the best opportunity of honoring me with an answer.”[19] History records no direct response to Duché by Washington, true to his statement to Hancock that if he had known the contents, he would have returned it unopened.

As stated earlier, the Declaration of Independence was a tipping point for Duché, even though he remained in the service of Congress after July 1776. He described in his letter to Washington how he rashly accepted the invitation from Hancock to address Congress following the Declaration, and dedicated his sermon to Washington out of utmost respect for him. “Farther than this I intended not to proceed. My sermon speaks for itself & utterly disclaims the idea of independency,” he added.[20] This is true—a thorough reading of his writings and sermons indicates gives no indication of any appetite for independence.[21]

An obvious possible motive for the letter was self-preservation. Perhaps he wrote after succumbing to British threats. Washington recognized this possibility, telling Hancock, “I cannot but suspect, that the measure did not originate with him, and that he was induced to it by the hope of establishing his interest and peace more effectually with the Enemy.”[22] His letter contained details regarding naval and military strength of the colonial forces that Duché was unlikely to have known and may have been supplied by his captors. Forced into it or not, Duché never repudiated his comments publicly or, as far as is known, privately. Says historian Spencer McBride, “Duché appears as a man overwhelmed by a set of once complementary allegiances turned incongruous by the Declaration of Independence. When we consider the full context in which he chose to abandon the patriot cause, [that] scenario is the most likely.”[23] Clearly, he was a man who had gotten in too deep in the volatile mix of religion and politics, and under the watchful eyes of his captors he was grasping for a life line.

Duché’s letter deeply wounded a certain rebel, his brother in law and Declaration signer Francis Hopkinson. In a “Dear Brother” letter which he penned in November 1777, Hopkinson wrote that “Words cannot express the grief and consternation that wounded my soul at the sight of this fatal performance. What infatuation could influence you to offer to his Excellency an address filled with Gross misrepresentation, illiberal abuse, and sentiments unworthy of a man of character?”[24] Adding fuel to the argument that Duché’s hand was forced, he added that Duché “assert[s] many things . . . which are far from being true” and that “it is impossible for you to be acquainted with.” Most poignantly he wrote, “I tremble for you, for my good sister and her little family; I tremble for your personal safety. Be assured I write this from true brotherly love.”[25]

Hopkinson chose to send the letter to Washington for forwarding to Duché, but the general never found the opportunity and it was returned to Hopkinson—Duché apparently never saw it. Washington remarked to Hopkinson in returning it that “I was not more surprized than concerned, at receiving so extraordinary a letter from Mr. Duché, of whom I had entertained the most favorable opinion, and I am still willing to suppose, that it was rather dictated by his fears, than by his real Sentiments”[26]

The Washington letter effectively destroyed Duché’s career in the colonies. Indeed, after its widespread publication Duché found himself cursed by Americans as a traitor and held in contempt by the British as a blundering fool.[27] In December 1777, he sailed to England and tried to right himself and his life. His wife and children followed his flight in 1780. Perhaps having angered Providence by his actions, Duché’s ship to England was driven off course and wound up in Antigua. He was offered a job there but due to the conditions of his parole and his presence on the British “Registry of Traitors,” he thought it wise to continue to England to try to clear his name. He was eventually pardoned.[28]

He spent his first four years of his personal penance in England serving in his downgraded position as chaplain of the Asylum for Female Orphans in St. George’s Fields. Unlike most Loyalist exiles, he had both the chance to continue his profession and an entree into English society among what he called “a happy circle of literary and religious friends.”[29] In the early 1780s, Duché’s conversion to the teachings of Swedenborg, a scientist and mystic who claimed he could freely visit heaven and hell and talk with angels, and certain eccentricities caused some to question his sanity more than his patriotism, resulting in some leniency for his treasonous actions.[30]

Still he yearned for his native Philadelphia, even though his home and property had been confiscated and he was prohibited from returning. Like many of his fellow Loyalists, he never imagined the war would last as long as it did. In 1783, after several fruitless appeals to friends still there to help him be allowed to return, he wrote a letter to Benjamin Franklin, with whom he had been close during their Philadelphia days, Franklin having known him since infancy. He appealed to Franklin as to whether “your Excellency would condescend to inform me, as soon as may be convenient to you, whether the Act of Attainder in which my Name . . . will be repealed in Consequence of the Treaty of Peace; whether there is the least Prospect of my being reimbursed any Part of the Sum for which my House &c was sold;” as well as asking to be reinstated to his position.[31]

Franklin did not respond, so Duché appealed to Washington, asking if the general would “join with my Country in pardoning this Error of Judgment? Will you yet honour me with your great Interest & Influence, by recommending, at least expressing your Approbation of, the Repeal of an Act, that keeps me in a State of Banishment from my Native Country, from the Arms of a dear aged Father, and the Embraces of a numerous Circle of valuable & long-loved Friends.”[32] Washington finessed his reply, sounding magnanimous on the one hand—“personal Enmity I bear none, to any Man—so far therefore as your Return to this Country depends on my private Voice, it would be given in favor of it with chearfulnes”—but stating that the ultimate decision belonged to local authorities.[33] Duché wrote to Washington again in 1789, congratulating him on being elected President, and again appealing for aid in returning to America. No response by Washington is recorded.

Duché and his family were finally allowed to return in 1793 and shortly thereafter he was pardoned by Gov. Thomas Mifflin. Amazingly, he was able to meet with Washington several months later. The meeting was reportedly cordial, though there is no record of what was said. Duché chose to stay in the city when the yellow fever epidemic of 1793 broke out. Though unscathed by the epidemic, Duché was slowed by a mild stroke he had suffered in England. It is unclear whether he was ever allowed to preach after his return to America. In 1797, his wife of nearly forty years, Elizabeth, died in a freak domestic accident. Just one year later, Jacob followed her to the grave and is buried in St. Peter’s Churchyard.

As for the Chaplaincy of the U.S. Congress, the position remains today, more perhaps out of custom than anything else given contemporary pressures to sharpen the separation between church and state. Ironically, James Madison, who with Thomas Jefferson was a key proponent of the church-state separation, had been appointed to the committee, in the first House of Representatives, responsible for creating rules to regulate the appointment of chaplains. He also voted for a bill authorizing payment of congressional chaplains.[34] When the issue came before the Supreme Court in 1983, Chief Justice Warren Burger wrote for the majority that “There can be no doubt that the practice of opening legislative sessions with prayer has become part of the fabric of our society. To invoke divine guidance on a public body entrusted with making the laws . . . is simply a tolerable acknowledgment of beliefs widely held among the people of this country” (463 U.S. 792).[35] This decision, which relied at least in part on Madison’s membership on the chaplaincy committee, remains in effect today.

For Jacob Duché, the first to occupy this position in a most difficult time in our history, only hard lessons resulted. In a turbulent and divisive time, his mixture of religion and politics proved disastrous for him. It placed him in a series of circumstances through which he was unable to successfully navigate,[36] and turned him from hero to villain.

[1]John Adams to Abigail Adams, September 16, 1774, Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-01-02-0101.

[3]On-Line Library of Liberty, The Works of John Adams, Volume 2 (Diary, Notes of Debates, Autobiography), 378.

[4]A. G. Olree, James Madison and the Legislative Chaplains, Northwestern University Law Review, 102(1), retrieved from search-proquest-com.ezproxy.bucknell.edu/docview/233353008?accountid=9784, 158.

[5]Clarke Garrett, “The Spiritual Odyssey of Jacob Duché,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 119, No. 2 (April 16, 1975), 147.

[6]Power of Attorney to Deborah Franklin, April 4, 1757, Note 5, Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-07-02-0070.

[7]“Jacob Duché’s American Vine,” people.smu.edu/religionandfoundingusa/jacob-Duchés-american-vine/.

[8]House of Representatives, Office of the Chaplain website, chaplain.house.gov/archive/continental.html. Another source, Lorenzo Sabine’s Biographical Sketches of American Loyalists, indicates this prayer was delivered after independence was declared in 1776.

[9]Kevin J. Dellape, America’s First Chaplain : The Life and Times of the Reverend Jacob Duché(Bethlehem, PA: Lehigh University Press, 2013), search-proquest-com.ezproxy.bucknell.edu/legacydocview/EBC/1504568?accountid=9784, 2.

[10]Garrett, “The Spiritual Odyssey of Jacob Duché,” 147.

[11]Spencer W. McBride, Pulpit and Nation: Clergymen and the Politics of Revolutionary America (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2017), search-proquest-com.ezproxy.bucknell.edu/legacydocview/EBC/4755336?accountid=9784, 59.

[13]John Galt,The Life, Studies, and works of Benjamin West, Esq. (London, 1820), 42. Fergusson had related the account to West.

[14]George Washington to John Hancock, October 16, 1777, Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-11-02-0537.

[15]Jacob Duché to Washington, October 8, 1777, Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-11-02-0452.

[19]Duché to Washington, October 13, 1777, Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-11-02-0505.

[20]Duché to Washington, October 8, 1777.

[21]Garrett, “The Spiritual Odyssey of Jacob Duché,” 147.

[22]Washington to Hancock, October 16, 1777.

[23]McBride, Pulpit and Nation, 63.

[24]Washington at Valley Forge, together with the Duché correspondence (Philadelphia: J.M. Butler, 1858), 69-73.

[26]Washington to Francis Hopkinson, November 21, 1777, Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0339

[27]“Jacob Duche—American Revolutionary War Patriot and Traitor,” www.revolutionarywarjournal.com/jacob-duche/.

[28]William Pencak, Pennsylvania’s Revolution (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2010), 105.

[29]Garrett, “The Spiritual Odyssey of Jacob Duché,” 150.

[30]“Jacob Duche—American Revolutionary War Patriot and Traitor,” www.revolutionarywarjournal.com/jacob-duche/.

[31]Duché to Benjamin Franklin, January 28, 1783, Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-39-02-0032.

[32]Duché to Washington, April 2, 1783, Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-10980.

[33]Washington to Duché, August 10, 1783, Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-11664.

[34]Olree, James Madison and the Legislative Chaplains, 154.

[35]Wendy Cadge, Laura R. Olson, Margaret Clendenen, “Idiosyncratic Prophets: Personal Style in the Prayers of Congressional Chaplains, 1990–2010,” Journal of Church and State, doi.org/10.1093/jcs/csv093, 5.

36McBride, Pulpit and Nation, 66

One thought on “Jacob Duché: Mixing Religion and Politics During the Revolution”

Though a very good read, the propensity to promote the phrase separation of church and state as a founding principle is disturbing.

The phrase does not appear in any of the founding documents. The establishment clause only prohibits congress from declaring a national religion, and prohibits them from interference in the act of the individual’s ability to worship to his / her conscience.

The only place it appears, said phrase, is the letter from President Tho. Jefferson to the Danbury Baptist Association of Connecticut, in his usual eloquent fashion of writing, reaffirming that he had no intention of interfering with their Right to worship.

And though the Supreme Court of the United States made that claim of separation of church and state as part of their decision in 1947, it is still today just as farcical as it was then to even make such a statement. They were injecting their own personal opinion into the decision. And it should be remembered that the Supreme Court is not the where-all end-all to all things constitutional either. That is beyond the sphere of their authority as they offer opinions.

I fear we have allowed the different branches to either assume too much influence and power and some of them to abrogate too much to the other branches for the point of increasing their public image.

Aside from that it was a very interesting reading.