To historians of the American Revolution, the date of 1775 for French participation in the Patriot cause may seem incredible. The enigmatic “Monsr Dubuq,” “Dubuc,” or “Dubuque” was nonetheless, one of the first French officers to assist in the American Revolution, before envoy M. Julien Bonvouloir,[1] and two years prior to the arrival of Baron de Kalb and Marquis de Lafayette in July 1777. As early as July 6, 1775, British Maj. Stephen Kemble reported “A Frenchman came this day from the Rebels says a French Man, one Dubuc, is their Chief Engineer, as Gridley cannot act from his Wound. Sent the French Man to the Provosts.”[2] A July 8 report states, “I am told ye French rebel that came ye other ev’g [evening] speaks English though he pretends otherwise . . . which he [General Howe] takes to be string proof he came over with some design.”[3] On August 17 Kemble reported, “The Capt. of the Man of War that Conveyed the inhabitants to Salem returned, and brought with him Monsieur Dubuque, a French Man, who had been employed by the rebels as an Engineer.”[4]

So just who was this mysterious French engineer Dubuq? The engineer who served the rebels at Boston in June, July, and August 1775 was probably Jean-Baptiste du Buq (1752-1787), son of Louis XVI’s Intendant des Colonies J-B “le Grand” Dubuc and a member of the Noailles Regiment (which, coincidentally, was led by Lafayette’s brother-in-law).[5] Dubuq sailed for Beverly, Massachusetts, from La Trinité, Martinique in late April 1775. His contact was Josiah Batchelder, a merchant member of the Committee of Correspondence at Beverly, who had traded pine lumber and building materials, along with salt cod, from Massachusetts for sugar cane products (molasses and rum, etc.) with the Dubuq family at Galion, La Trinité, Martinique, as early as 1769.[6] Dubuq’s schooner, captained by Nathaniel Leach, a Batchelder associate, was intercepted by the British sloop of war Nautilus off Cape Cod before he was allowed to make his way to Beverly and Salem. Dubuq wrote that Gen. Israel Putnam brought him to the American Camp at Cambridge in a chaise on June 4, 1775.[7]

At General Putnam’s request, Dubuq went to New London, Connecticut, in early June 1775 on a mission seeking gunpowder suppliers and returned to the “Rebel” camp just after the Battle of Bunker Hill. He then served as “chief engineer” in the place of Richard Gridley who had been wounded in the thigh during the June 17 battle. Dubuq wrote about his construction of earthworks at Winter Hill and Prospect Hill under Putnam in June. In early July, Gen. Charles Lee ordered him to view the New Hampshire lines under the command of Gen. John Sullivan and Col. John Stark, with headquarters at the Royall Mansion in Medford.[8]

Dubuq then visited Danvers, Marblehead, and Newburyport, and heard Pres. Samuel Langdon’s speech at Harvard revealing the colonists’ ambitions for “Free Trade.” Dubuq wrote to the French colonies in the Caribbean for powder, some of which arrived from St. Domingue (Haiti) for the Provincial Massachusetts Committee on Supplies soon after August 8.[9]

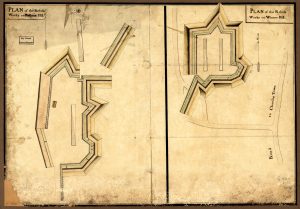

A “French Redoubt” is clearly identified between Prospect and Winter hills in Medford on the 1775 map of Boston and Environs by Henry Pelham, showing that the work bore that name in August.[10] The redoubt is shown in other detailed drawings of the “Rebel Works” on Prospect and Winter hills.[11] Washington had visited the new entrenchments soon after his arrival in the area, and wrote from Cambridge to John Hancock, President of Congress on July 10: “I arrived safe at this place on the 3rd instant. . . . Upon my arrival I immediately visited the several posts occupied by our troops . . . on our side we have thrown up intrenchments on Winter and Prospect Hills . . . the enemy’s camp in full view, at a distance of a little more than a mile.”[12]

After leaving the rebels and coming in to Boston, on August 20 “Monsr Dubuq” wrote two letters to British Gen. Thomas Gage, with several pages of detailed observations identifying his family connections and describing his visit to New England from April to August in service of his King (Louis XVI) and the American rebels, including the construction of the “French Redoubt.” In an apparent ruse to gain passage back to Europe he even offered his service to Gage himself.[13] The first letter, from “Monsr. DuBuq, A Frenchman who left the rebels among whom he served in quality of an Engineer,” written in French and translated by this author, began as follows:

To His Excellency General Gage, Commandant of His Majesty’s Troops . . . My journey in this country was to have been for only two or three months after which time I planned to return to my country. I had the misfortune to let myself be deluded into the cause of the Americans and my services were received. I was employed by them in the quality of an engineer. The works I made were situated on Winter’s Hill adjacent to Prospect Hill on the Medford side.[14] The slopes of Prospect dominate the Cambridge river [and] are very well fortified by the works and the situation. The rear would be little accessible. . . . As to whom the entrenchments are for in particular I could not tell in all exactitude as to proportions and their situation, but the plans which I could make in giving perhaps an idea. . . . Dubuq.[15]

A second letter written by Dubuq to Gage in English the same day, August 20, gave details of his visit in a letter of introduction (in French) with his family connections:[16]

Dear Sir,

As for further information in my regard you will please be able to take in receipt of Mr. Dubuq de Bellefond Commandant of the battalion of la Trinité of Martinique, Mr. the Count of Choiseul-Meuse, Brigadier of the armies of the King and governor of Martinique, Mr. Dubuq Superintendent of Commerce of the Colonies to enable to assure you, I flatter myself, Sir, That by saying to you that I belong to them, they will add advantageous accounts on my behalf. I have the honor to be with profound respect, Dear Sir, of your excellency, The very humble and very obedient servant,

Dubuq

Dubuq continues with his lengthy account in English documenting his role as engineer and his sourcing of powder supplies for the rebels as well as providing many interesting details of the American officers, soldiers, and conduct during the siege of Boston:[17]

Dubuq—Boston August 20th 1775

To His Excellency General Gage commanding his majesty’s forces in America

I have already the honour to write you some reflections about the rebels and their measures, but I shall believe to have quite satisfied but when I shall have given you a more particular account on the same subject and my behaviour since I left my country. I shall begin if you will give me leave.

Departed from Martinico the twenty third of April with a mere desire of traveling and being back in three months. Captain Leach was the master of the vessel, and was bound for Beverly. Off Cape Cod, we were brought to the sloop of war the Nautilus, Captain John Collins. The Lieutenant, Mr. Will Brown, took charge of the schooner which he carried into Boston. We cruised three days more, and came to anchor in the harbour. The schooner was cleared and brought by the Nautilus under the protection of another sloop of war at Marblehead. The day after we had leave to go to Beverly; the kindness I received from Captain Collins and all the officers on his board afforded me sufficient reasons to engage my coming and offer you my services; but deprived of any acquaintance who could protect that resolution, I durst not get into Boston and I followed my former idea. The day after my arrival in Beverly, I went in Salem where I settled to spend the time I purposed. Many persons suspecting that I had served in France engaged me to offer my services; young and inexperienced, their impressions prov’d it and I wrote to Mr. Putnam. He answered and fournished me a chaise to go in the camps. His letter is dated June the fourth and is now in the hands of Mr. Lee.[18]

I rode to Cambridge the same day. He [Putnam] enquired a great deal from me about the quantity of powder which could be in our French Islands, and engaged me to write for getting some from thence. About eight days after, I departed for New London. I wrote in Martinico to Mr. Olivier St. Pierre, Guadeloupe to Mr. Caramajor Basseterre and Hispaniola to Mr. Brocas, Port au Prince. A merchant in New London was to dispatch a vessel in the fortnight.[19] I heard in that town the new[s] of the Battle at Charleston [Bunker Hill] and soon departed for Cambridge where I found faces quite disturbed; they were then entrenching on Prospect Hill; Mr. Putnam ordered me to fortify with some intrenchments [on] Winter’s Hill. When I did I was encamped with two other Frenchmen, one Mr. de Longchamp. Then arrived in Cambridge Mr. Washington and Mr. Lee.[20] Mr. Lee sent me the day after his arrival to survey the lines of New Hampshire which I have already had the honour of speaking to you of. As I was going I met with Mr. de Longchamp who was a-coming from Medford and made his escape in your camps on Bunker’s Hill. Since that day, I conceived the resolution to fetch for an occasion of coming and offer you my services in the Kin[g]’s army. I reflected on the inconsequent proceeding which has brought me amongst the rebels but I could not effect my design by the same way as Mr. de Longchamp, I mean thro’ their guards. Besides not willing to go off as a coward deserter. I wrote a letter to Mr. Lee whereby I presented him of my retreat and asked him for a pass to go to Canada, hoping that it could serve me to go to Portsmouth where I intended to get aboard the Scarborough, Captain Barclay. Mr. Lee and Mr. Putnam assured me they suspected no connection betwixt Mr. de Longchamp and me and promised me a commission if I agreed to stay. I resoluted to take it to support me in the meantime I would find an occasion to come to you. Then I left the camp and lived in Medfort [Medford]. I have always been there since and walked sometimes in Cambridge and the camps. The last time I have been is Monday last week. I departed the Wednesday to go and get a passage in Newburyport for Martinico. I found it by a vessel which was to sail in but three weeks. Hearing that a sloop of war was come to Salem to escort the transport which brought the poor of Boston I resoluted to try every mean[s] to go aboard, and the vessel for Martinico was but my camp-de-reserve. I returned to Medfort on Saturday morning. The foggy weather made me hope that the man of war could not sail; but at my return in the afternoon I found I was quite deceived. I went to Danvers to wait for an occasion of going by sloop to Marblehead where I heard the man of war had sailed. The sailors of that little town were too much kept by their arming a dozen of privateers. They employed to that work all last Sunday. I have yet heard a noise that they would have the same week six hundred men to mount them. I embarked then at Marblehead Tuesday in the afternoon. I went thro’ the ferry in a little boat to get where that of the Merlin was taking water. I went on the frigate and left in the town of Marblehead a bundle of some of my cloathes. I was very much flattered with all the politeness I proved from Captain Barnaby and all his officers. I felt them a very great difference between the gentlemen amongst whom I was and the coarse rebels I had lived among before at the dock. The Captain made me the kindness to lend me his man to go ashore and try could I get the things I had left in the inn. What gave me that confidence is that I had been thought in the morning by all the peasants to belong to the man of war. We were stopped three times by their guard and seeing how much I was in danger to be catched I gave up my design and went aboard the frigate.

As to the epoch of the going off of Mr. Longchamp, the day after the rebels seeing the floating batteries mounting the river drummed an alarm. ‘Twas over all on Prospect Hill which Mr. Putnam commanded when they perceived that the King’s Troops were not going to form the attack, every soldier went in his tent. I think if they had not so soon come from that alarm they would have been in the plain to face the regular troops at their landing. As for their gathering together they do it very quick—as soon as the drums beat they are under arms. They use to fear an attack when they see floating batteries mounting the river.

For the number of their guards at night reinforcements, I can give you but conjectures as it was a service very different from that wherein I was employed. They relieve it in the morning and I doubt very much it be reinforced in the night. It is pretty numerous, but I think they inspect not very exactly when going upon that duty. The soldier arms are in general in a pitiful state. I have seen some which were not of caliber and others garnished with unfiring flints. The little discipline which does not subject the soldier to clean his arms shall support more and more that abuse; ‘tis yet thought very common among them that the suns reflection on the bright arms of the King’s Troops disturb them from taking a just sight.

They have on Winter’s Hill two brass field pieces taken at Quebec. They have four pounders in the main road from Cambridge to Watertown. They have eight pieces of cannon, some field pieces and all the different pounders. They have lately received from the north two very large guns of four and twenty to six and thirty pounds. They minded to place them on Prospect Hill in the Bastion which commands the river. As for chevaux de frise they have but five or six in all the intrenchments in Cambridge. Tis not, as far as I could discover, a means of defense they are very fond of using of. Since the light horses are arrived they order’d for fifteen hundred halberds eight feet long. They placed them all by the entrenchments for the case they should be attacked by that corps.

Tis any ground to believe they shall feel misery very soon. The most part of the soldiers are very unclean, often without stockings, and lying in straw what gets them very lousy. Great many amongst them who are sick, over all of the troops of Mr. Putnam, if I recollect well, but this fortnight one of his rebel officers is dead with the small pox.

Powder is pretty scarce. I doubt of the new I have heard the last days, they had received such and many other falsehoods the less poor wits amongst them find to support the spirit of the crowd. They fancy they will make a free trade with all the nations of the world, and the strangers will fight to enter into their ports. Such was the respectable talk of the president of the college[21]in his free enthusiasm.

As for the generals, there is but General Lee who has any experience; he is a very alert man, always surveying the lines and posts. He walked about all the night of the attack by the riflemen. General Putnam is a very good soldier, and General Washington a very rich man.

In all the time I have spent amongst those rebels I have been but once to Roxbury in the intrenchments which command the river of Cambridge [Charles River]. Then they had no gun there and I have perceived it was protected westwards but by the situation.

They generally reckon a greater number of troops in Roxbury than in Cambridge, but I don’t believe in all, the army of the rebels over goes twelve thousand men amongst which a great many of a mean age.

For conclusion, Sir, they are but a parcel of rebels governed by a tyranny of which they can’t fail to know soon the difference from the happy constitution under which reason ought to maintain them. I know the inconsiderate proceeding which engaged me amongst them. I am more to complain than to be condemned on it. My account is but the interpretation of my changement of my sentiments, I pray you to be persuaded of it and to believe that I am yours to command, to expose my life for the defence of this cause I esteem the best.

I am with a very great respect, Sir, Your Excellency’s The most Humble and most obedient Servant,

Dubuq

The appearance of M. Dubuq and his “French Redoubt” built at Boston during the siege in June 1775, predates by two years Lafayette landing in South Carolina, and opens new insights into the causes and foreign resources of the American Revolution. In 1885, the City of Somerville built a memorial at the site in a park on Central Hill, that was subsequently destroyed. The site is now occupied by Somerville High School and Library.

[1]Bonvouloir was the secret envoy of Vergennes, the French minister of state, through whom negotiations were opened in 1775 that resulted in French intervention for American independence.

[2]“Journal of Stephen Kemble,” Collections of the New York Historical Society (New York: New York Historical Society, 1883), 47; MA Archives 137-8. Col. Richard Gridley, Chief U.S. Engineer, was wounded at Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775.

[3]Dubuq to Thomas Gage, August 21, 1775, Thomas Gage Manuscripts, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[4]“Journal of Stephen Kemble,” 55.

[5]Arbres Généalogiques sur Toujoursla, GeneaNet.org. Dubucs who served during this era include Abraham du Buc de Marcussy (de Marentille, 1761-1825), a sous-lieutenant in the Agenois Regiment which sailed with de Grasse from Martinique to Yorktown, and his brother Jean-Baptiste de Buc de Marcussy (1752-1787). Gilbert Bodinier, Dictionnaire des officiers de l’armée royale qui ont combattu aux États-Unis pendant la guerre d’Indépendance3d ed. (Château de Vincennes, 2001), 172-73.

[6]Dubuq apparently went to Beverly with an introduction by Dubuq de Bellefond, commandant of the battalion of the Trinity of Martinique, a correspondent and trading partner of Josiah Batchelder. Batchelder was on the Committee of Correspondence and Safety in Beverly, Massachusetts from 1773 until the end of the Revolution. Josiah Batchelder Papers, Series 3, B and C, 36 and 37 Correspondence and Bills in French: 1769-1776, and 1777-1792, Beverly Historical Society, Cabot House.

[7]Dubuq to Gage, August 21, 1775.

[8]Charles Lee quartered early in July with his famous dog Spado at the Royall Mansion, that he christened ‘Hobgoblin Hall’ in Medford. John Sullivan and John Stark were also quartered there. Washington later moved Lee and his dogs headquarters to the Oliver Tufts House, still standing nearby. Somerville Historical Society.

[9], James Swan recorded on August 8, 1775 that the first foreign military supplies (probably those ordered by Dubuq), in which the Committee of Safety had an interest, were soon to arrive from Cap François, St. Domingue. The Committee Appointed to State the Disbursements of this Colony in the Defense of American Liberty for the consideration of the Continental Congress: Col. James Swan account, 1775 Provincial Committee Accounts, Massachusetts Archives.

[10]“A PLAN OF BOSTON IN NEW ENGLAND with its Environs . . .With the Military Worksconstructed in those places in the Years 1775-1776,” Henry Pelham. The pass that he was granted to do the survey for this map was dated August 21.

[11]These were likely re-drawn by British Engineer Col. John Montresor based upon Dubuq’s plans. See John Montresor, “Draught of the Towns of Boston and Charlestown and the Circumjacent Country shewing Works thrown up by his Majesty’s Troops,”Map Division, Library of Congress.

[12]Final Report of the Boston National Historic Sites Commission(Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1961), 232-236. Also “Forts built prior to Washington’s Arrival” in Somerville Historical Monographs “George Washington in Somerville” by George Hill Evans, Librarian, Somerville Public Library, 1933, sub-committee on Study and Research of the George Washington Bi-Centennial Commission, appointed by Mayor John J. Murphy in 1932. Somerville Public Library.

[13]Dubuq to Gage, August 21, 1775.

[14]The “French Redoubt” is shown on Henry Pelham’s map.

[15]Dubuq to Gage, August 20, 1775, Thomas Gage Manuscripts, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[16]“Monsieur, Quant àde plus amples informationsà mon égard s’il vous plait En prendrez vous pourrez en reçevois de Mr Dubuq de Bellefond Commandant du battaillon de la Trinitéde la Martinique, Mr le Comte de Choiseul-Meuse brigadier des armies du Roi et gouverneur de la Martinique, Mr Dubuq surintendant du commerce des colonies pourer encore vous en donner, je me flatte, Monsieur Qu’en vous disant que je leur appartiens, ils ajouteront des comptes avantageux sur ma conduite. J’ai l’honneur d’etre avec un trés profound respect, Monsieur, De vôtre excellence, Le trés humble et trés obéisant serviteur, Dubuq.”

[17]Final Report of the Boston National Historic Sites Commission,232-236. Also “Forts built prior to Washington’s Arrival” in Somerville Historical Monographs.

[19]“By a vessel which arrived here on the 30th ult. from Cape François [St. Domingue, now Haiti], we are informed that the Captain of the vessel sent from this port to the Cape for a quantity of warlike stores, in which the Committee of Safety for the Colony of Massachusetts had interested themselves, had executed his commission and was to sail with a large quantity in a day or two so that she may be hourly expected.” Nicholas Cook to George Washington, Providence, August 8, 1775, Revolution Miscellaneous 1774-83 Vol. 138 p. 262-9; Reports 1774-83, Vol.137 p. 19, Massachusetts Archives. Correspondence between John Adams and Massachusetts Provincial Council president James Warren confirmed a shipment of 7,000 pounds of powder was en route to Boston between July 24 and August 9, 1775. John Adams to James Warren, July 24, 1775, in “Journal of Stephen Kemble,” 52-54; Warren to Adams, August 9, 1775, Adams Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[20]“Forts built prior to Washington’s Arrival” in Final Report of the Boston National Historic Sites Commission, 3, 232-236.

[21]Samuel Langdon acted as chaplain to several American regiments on August 15, 1775 including that of Col. John Glover. (Langdon Papers, Harvard University Archives.) Dubuq may also have seen a sermon by Langdon published as Government corrupted by vice, and recovered by righteousness: A Sermon preached before the honorable Congress of the colony of the Massachusetts-Bay in New England, assembled at Watertown, on Wednesday the 31st day of May, 1775. Being the anniversary fixed by charter for the election of counsellors, Samuel Langdon, D.D. president of Harvard College in Cambridge (Watertown, MA: Benjamin Edes, 1775).

10 Comments

Thanks! Sharing on Facebook Group Pages for American Revolution Round Table of Northern Delaware and W3R-US (Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route).

I appreciate your positive feedback! It is amazing to me that this French engineer Dubuq and his “French Redoubt”( clearly mapped by Henry Pelham, artist J.S.Copley’s half brother in 1775-6) have remained unrecognized for so long. I have much information on his family, of whom other members were in Boston from 1791 – 1793, and descendants who remain in Paris. I also am familiar with Bob Selig and the W3R program. In fact I grew up in Scotch Plains NJ that was the site off one of the camps on the W3R march. As a member of the American Friends of Lafayette, I am glad to have you share the link to this article.

Excellent piece, and a great illustration of the Bunker Hill / Breed’s Hill confusion that continues to THIS very day. It’s not just our schools today that confuse the two hills, but even the British of the day. Look at the title of the main etching here: “Battle of Bunker’s Hill”. Nope, no fighting took place at Bunker; it ALL took place at Breed’s Hill.

I have a theory as to why the confusion, but can a real historian explain to me why the British, in control of Boston for years, got the two names switched ? Even the Museum there won’t return an answer to me about this … frustrating.

No British writer gave an explicit reason for the name chosen for the battle, but modern concern about it is largely semantic. There are many cases of battles not being named for the specific ground on which they were fought. The Battle of Bennington in 1777 is named for the town that one side was trying to reach; the Battle of Waterloo is named for the place where the British commander had his headquarters; etc.

In the case of Bunker Hill, the British objective was, in fact, Bunker Hill – before any American activity on the peninsula, British plans were to build a redoubt on Bunker Hill facing American positions. With the construction of an American redoubt on the peninsula, there was an obstacle in the way of the British objective, which was still Bunker Hill. Having driven the Americans off the peninsula, British forces proceeded to build a redoubt on Bunker Hill, their original objective. From a British perspective, the purpose of the battle to occupy Bunker Hill, and the battle was fought to achieve that objective; the American redoubt on Breed’s Hill was an obstacle to that objective.

What a fascinating tale! – a couple of things stood out for me. With regard to the site of his “French Redoubt,” I know the Somerville High School site very well. It is right next to City Hall and this last January I had the pleasure of lecturing at the High School in preparation for my speech at Prospect Hill for the New Year’s Day commemoration of the raising of the Grand Union flag over the new establishment of the Continental Army (the Army of ’76). The history embedded in the area is palpable and I’ve had the good fortune to witness the locals’ passion for it. I understand the area of Prospect Hill was much higher ground than it is today, but when standing atop the monument and gazing in the direction of Bunker Hill, you get a sense of what a commanding position it was during the Siege.

Additionally, the mention of “halberds,” is very good evidence of Gen. Nathanael Greene’s orders to use wooden “spears” in the event of an attack based on the desperate shortages of powder.

“Tis not, as far as I could discover, a means of defense they are very fond of using of. Since the light horses are arrived they order’d for fifteen hundred halberds eight feet long. They placed them all by the entrenchments for the case they should be attacked by that corps.”

Thanks for your very interesting piece,

Byron DeLear

It is great to hear from local historians who are interested in the Siege of Boston and the “Rebel” earthworks on the hills in the environs. I was also interested, in addition to Dubuq’s comment about the halberds, that he also reported the desperate state of the rebels’ powder supply as well as the sad condition their muskets. It was enlightening to hear that their excuse for letting them rust was that they thought the reflection off the shiny British musket barrels disturbed their sight! I have also seen plans of the Rebel fortifications that had what looked like tree branches pointing outward from the works to act as chevaux-de-frise.

I disagree. I find no problem with your analysis, BUT understand, it was the British maps of that period that clearly switched the names of those two now famous hills, one of which became famous for the Patriots’ defense.

My question is simple: why did the map makers switch the two names ??

You write, “it was the British maps of that period that clearly switched the names of those two now famous hills.” Sounds like you’re referring to the map “Boston its Environs and Harbour with the Rebels Works . . . from the observations of Lieut. Page” which can be seen here:

https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3764b.ct000070/?r=0.233,0.145,0.236,0.097,0

But not all British maps of that period switched the names; here are two others, for example:

https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3764b.ct000252/?r=0.224,0.175,0.695,0.285,0

https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3764b.ar093200/?r=0.434,0.151,0.222,0.091,0

So—one mapmaker made the mistake, and that map was reproduced, but no more widely than other maps. We can’t say that the mistake on this one map is the reason that the battle came to be called Bunker Hill—after all, Americans have called it that ever since it happened, not just British writers, and the battle has figured far more prominently in American memory than in British memory. To your question of why this one map has the names wrong, I have no idea.

Great map references—Thank you, Don. Henry Pelham’s is still the most accurate from the Boston perspective since he included not only the layout of both Patriot and British defensive works, but also included the layouts of the Tory Row estates in Cambridge with outbuildings and garden plots. He even showed in detail the estate of Gov. Shirley, not on most other plans of the siege of 1775-6. The real point was not the nomenclature of Bunker/Breeds Hill, but the fact that, although Dubuq was then in New London ordering powder for the patriots, due to Gridley’s wound he then became the first French engineer to serve the patriot cause. He was followed by a line of distinguished French engineers who founded and trained the US Corps of Engineers: Louis Lebègue Duportail (1743-1802), Louis de Tousard (1749-1817), Stephen Rochefontaine (1755-1814), and Guillaume Tell Poussin (1794-1876).

The first picture doesn’t depict the American position on April 19th. That would be more like Putnam’s position on Prospect Hill in July, 1775. As my 4th great-grandfather, Caleb, wrote in his diary:

July 24th, Monday.

Today all the troops under command of Brigadier General Putnam, except Colonel Little’s regiment [Caleb’s Regiment], were ordered to march from Prospect Hill, to be stationed elsewhere, their vacancies to be supplied with troops from Cambridge, Winter Hill, etc., under the command of Brigadier General Green.

It’s interesting. I found this article after I posted an excerpt from the diary on my Facebook page. Between July 12th and 27th, Caleb mentions the desertion of a number of British soldiers into the American lines and the Massachusetts Historical Society has an article on psychological warfare relative to this time and Prospect and Bunker’s Hill. There were slips of paper sent into the British lines comparing what soldiers could expect on each hill (Prospect for the Patriots and and Bunker’s for the British).

If there is any confusion over the name of the battle, it was fought for control of the key strategic position, Bunker’s hill, and one of the American officers decided to entrench pn the more forward and untenable position of Breed’s hill. Once the British had cleared the Americans from the Charlestown Peninsula they fortified Bunker’s hill and were able to fire on the American lines in Cambridge with artillery they emplaced there. Textbook siege craft that had been overlooked by both sides and finally corrected by the British on June 17.

I discovered this article here when I was researching the phrase “French lines” in this entry in Caleb’s diary:

July 26, Wednesday.

This morning our regiment was ordered out of the great Fort [on Prospect Hill] to man the French lines — where we are for the future to repair in an alarm. A grenadier, belonging to the enemy’s side when on sentry, quitted his post, came over to us and delivered himself a prisoner to our guards. The whole regiment off duty.