Today, Jacob Jones’s portrait as a naval officer hangs in the assembly room of the Old State House in Dover, Delaware. It honors his victory in one of the first five naval battles of the War of 1812. That victory was the only one not won by a stronger American frigate; it was between the United States sloop-of-war Wasp and the British sloop Folic, ships of equal power. It refuted the excuses of the British admiralty and demonstrated to Parliament that no longer could “Britannia rule the waves” with impunity. Jones was honored by the nation equally with the victors of the other battles: David Porter, Isaac Hull, Stephen Decatur, and William Bainbridge.

At his burial in Wilmington, Delaware, in October 1850, his “Life, Character, and Services” were eulogized by John M. Clayton, Delaware’s long-time U.S. congressman and senator, at the time serving as U.S. Secretary of State. He noted that, “much of the history of his early life is lost.”[1] One eminent naval historian has stated that “merely citing the record in the case of Jacob Jones leaves a great deal unexplained.”[2] One unexplained thing is why Jones gave up his profession as a doctor, his secure position as clerk of the Delaware Supreme Court, a wife and child, and at age thirty-one entered naval service in 1799 as a midshipman for the Quasi-War with France. That is a rank normally used for boys of twelve to sixteen. As one biographer wondered, “Why did he do this? No one can answer.”[3]

Some remarkable events occurred during the week of February 11–18, 1776, in Lewes, Delaware, that the nearly eight-year-old Jacob Jones plausibly could have witnessed. Perhaps his reactions to those events created an interest in the navy. Over the ensuing years, living in Lewes throughout the Revolution, that interest may have grown into a dream of becoming a naval officer.

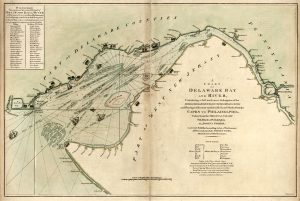

The small town of Lewes, Delaware, lay inside Cape Henlopen on the western side of Delaware Bay. The cape formed a roadstead where ships picked up pilots before proceeding up the narrow, shoaled channel to Philadelphia, the capital and largest city in the rebelling colonies. The town itself was set back from the bay and roadstead by a stretch of common-use marshland and a creek.

Jacob Jones had been born in March 1768 in central Kent County, Delaware. He had been orphaned by age six, and now at almost seven years of age he was living with his stepmother, Penelope Holt Jones, in the Holt family home in Lewes. Penelope had just inherited the home from her grandmother.

The home was located on the corner of Mulberry and Second Streets in the center of town. On the next lot to the southeast was the town’s principal inn, primarily used as a meeting place for lawyers conducting business at the county courthouse, itself the next building to the southeast of the inn. Beyond the courthouse was the graveyard of St. Peter’s Church and further southeast was the church on the southwest corner of Second and Market Streets. Across Market on the southeast corner was the mansion of the Rodney family, the most prominent in town. Directly across Second on the northeast corner of Second and Market Streets was the county jail and beyond that, the market. In that short block looking to the southeast about 100 yards along Second Street from Jacob Jones’s home could be seen all the elements of a civilized society: hospitality, the law, the church, prominent families and further beyond, commerce.[4] That was Jones’s world and he could roam it at will.

From about four until five in the waning afternoon sunlight of Sunday, February 11, 1776, five ships sailed into Lewes roads.[5] These were the first five ships of the Continental navy—Alfred, Andrew Doria, Columbus, Cabot, and Providence. Their arrival had long been anticipated. Nevertheless it came as an unpleasant surprise to the pilots of Lewes who had anticipated having the honor of guiding the first ships of the Continental navy to sea. As they rowed out to offer their services to the captains, they found that the ships had been brought south by Philadelphia pilots.

This was in violation of the arrangements taken by the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety to defend Philadelphia from attack up the bay. The principal defense was to be the rehabilitation of the former British fort on Mud Island, or Fort Island, and the placement of two ranks of chevaux-de-frise to block the channel approaching the fort.[6] After the placement of these obstructions, the committee commissioned ten pilots to lead ships past them. Five pilots were based in Philadelphia to take outbound ships down the river into the bay as far as Chester, Pennsylvania. Five pilots were based in Chester to bring ships into Philadelphia.[7] In order to stop these pilots from being captured by British ships and forced to guide them up the bay, the port naval officer at Philadelphia was instructed to insure they did not go farther down the bay than Chester. He was to have each ship master take an oath that he would discharge his pilot before issuing the ship a certificate to pass the obstructions. Ships had to go the rest of the way down the bay without a pilot unless they were convoyed by a Continental naval ship.[8] Additionally, the committee directed that:

all Pilots of the Bay and River Delaware ought to lay up their Boats, on or before the 20th day of September . . . [1775]. That any Pilot, or other person acting as a Pilot. . .who shall refuse or neglect to lay up his Boat or Craft, or who shall put himself in the way of being forcibly taken on board the King’s Ships, or who shall voluntarily serve . . . shall, on proof . . . be deemed an enemy to American liberty, a traitor to his country[9]

The Lewes pilots were angry and they immediately sent a letter of complaint to the committee.

According to your Resolves, the Pilots belonging to Cape Henlopen, have laid up their Boats, and are determined not to brake through them [the resolves]; if you will make the Pilots of Philadelphia doe the same, for it is very hard to see your Pilots come down and take the Bread out of their [i.e., our pilot’s] mouths . . . for as long as you admit them to fetch their Boats with them, they will do the like . . . . Henry Fisher, Luke Shields, John Learmouth and Samuel Edwards.[10]

Despite their anger, the pilots could not help but admire these ships. They had taken all of them to Philadelphia as merchant ships at one time or another. Now, as they came alongside, they could see that the ships were different. Most impressive was the thirty-gun flagship Alfred. She had been John Barry’s Black Prince and was still recognizable by her figurehead. She was now painted black below the waterline with gold sides broken by gun ports with black moldings and topped with a black gun ridge. Her rigging looked larger and stronger.[11] When going aboard, they were amazed at how shipshape the decks were.

The arrival of the vessels provided the opportunity for a grand Sunday afternoon outing for the people of Lewes. The weather was fine for February, approaching the 50s and sunset was at 5:20 with twilight lasting from 5:28 until 6:20.[12] They had easy access by the new bridge at the end of Market Street and across the well-worn, mile-long path through the common marsh to the bay front.

John Rodney was a family man, a close friend, confidant, and legal representative of the Holt family, and their neighbor just up Second Street.[13] His two sons, Daniel and Caleb, were schoolmates and pals of Jones.[14] They undoubtedly admired the first warships that they had seen, flying the new flag that Congress had just adopted in December to serve as the Grand Union flag. It had been first raised by Lt. John Paul Jones at the stern of Alfred.[15] What an inspiring sight for a boy of seven! The first warships he had seen and the new flag of the United Colonies.

Over the next several days, the first lieutenants and midshipmen from the ships were in town accompanied by working parties of sailors visiting the town market and Dodd’s general store and ship chandlery.[16] They were arranging for the purchase of provisions and supplies that they had consumed while spending over a month ice-bound at Reedy Island. Groups of navy men converged on Second and Market Streets in the early morning, where the boys could see them as they headed down Second Street to school.

The uniforms of the officers were splendid, perhaps more so than anything that the boys had seen before.[17] They wore cocked hats, long blue coats with red linings, lapels and cuffs, plus gilt buttons over red vests and blue breeches. The most impressive aspect of the officers’ appearance was the scabbards from which protruded the gold handles of swords and the wide swagger with which they walked. Some officers were walking behind the sailors of the working party with their swords drawn and herding them along like prisoners. Those officers seemed to be only about the age of Daniel Rodney.[18] Jacob Jones studied how they acted, if only to mimic them in mock battles he and his friends would enact after school. No longer would their battles be Minutemen versus Redcoats. It would be naval officers leading boarding parties. One of the officers leading one of the working parties also caught young Jones’s eye because he was so active and aggressively commanding, yet he so short and wiry. Wouldn’t it have surprised Jacob to learn that the officer leading one of the working parties had recently taken the name of “Jones”?[19]

Provisions were not the only reason the officers came to town. They needed men to fully man their ships. They were visiting the taverns and walking the streets of Lewes looking to recruit, by drink or sword, able men to go to sea. There were not enough volunteers or recruits in Philadelphia to man the ships. Congress regularly gave permission for captains to recruit men who were in jail for minor crimes by offering them the chance to be released if they would sail with the fleet. Many took the opportunity. Then, they soon deserted.

After sailing from Philadelphia at the New Year, these ships had been stranded by ice for more than a week in the Delaware River and for several more weeks at Reedy Island. That was when many of their men took the opportunity to desert and run. All the ships were affected with the problem. The Andrew Doria, under Capt. Nicholas Biddle, lost twelve men.[20] One of those was William Green, who had served as a carpenter in the Pennsylvania navy but had been removed as a mutinous troublemaker and later jailed as a debtor. To gain his freedom, on December 19, he had petitioned the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety to serve in the Continental navy, stating that he was “desirous of serving his country” and of “being of some useful service to society.” His release was granted the same day.[21] He signed on Andrew Doria on January 4 just as the fleet was departing Philadelphia, and deserted on January 10 at Reedy Island.[22] The ship could ill afford the loss of such a qualified man. To hide, Green had made his way to Sussex County where he was detained as a deserter and then also found to be a debtor. He was being held in the county jail in Lewes on that latter charge.

On Friday, making preparations to sail soon, Lt. James Josiah, first lieutenant of Andrew Doria, and a party of green-coated marines came into town expecting to collect men, volunteers, vagrants, or deserters. He discovered Green in the jail along with three others. He wanted them all, but especially had to have Green.

Because Green was being held on the separate charge of debt, Lieutenant Josiah found that Sheriff Boaz Manlove, already no friend of Congress, would not release him without authorization by the court.[23] In any case, the men would not come out of the jail. The militia was called, and failing to get the prisoners to come out, decided to starve them out. A large crowd began to form around the jail, spilling into the intersection of Second and Market Streets. Young Jones could have seen the crowd and militia milling about, just 100yards away from his home.

Lieutenant Josiah had returned to the ship and reported the stalemate in Lewes to Capt. Nicolas Biddle, commanding officer of Andrew Doria. Late in the day the crowd had thinned, but there was a loud clamor. Captain Biddle had come ashore. He entered the courthouse, just yards from the front door of Jones’s house. Then, as Biddle told his sister:

twas near five Oclock before I got ashore . . . turning Orator . . . [I said] This Man, May it please the Court and you Gent. of the jury, was put in Phila: Goal for Raising a Mutiny in the [Pennsylvania Navy] Gallies and I Obtained an Order of the Committee [of Safety] to take him out. Provided he enterd into the Continental Service and on no other terms would he have been Released. I beg the favoir of the Court to Read a Resolve of Congress Respecting the arresting of Men entered into their Service which is directly in point. And which I hope you will allow aught to Supercede all other Laws whatever . . . if you make a d[i]stincktion between the Goal and Goal Yard [naval service] . . . Your Laws differ from those of the Rest of the World. They are both equ[a]lly Places of Confinement. I again say such Procedure is without Precedent in any other Laws & derectly against those of the Congress . . . I should be very sorry to have the least Cause to Suspect this County of want of firm[ness] in the Cause. But Really this Conduct seems Calculated to counteract their [Congresses’] Measures. I shall only add that it is in your Power to give Me the Man as you plainly see that He is not nor cannot be Legally detaind. If I am not to have him, Let me know the Men by whose power & Authority he is kept in Order that I may transmit their Names to the Congress, And let them take order in the Matter.

When the jury foreman said “We will send for his Creditors and talk with them,” Biddle responded “What!!! Whenever I Ship a Man I must send through the Provinces or Continent to know to whom he is indebted and whether or not tis agreeable to them I should have him?” To that the foreman responded “Oh damn. I believe you may take him.”

Biddle said, after “Breaking the Goal Door . . . the Four Raskels stood on their defence. Barricad’d their Room door which Obliged me to force it.”[24] Somehow Green had acquired a weapon and was ready to defend his small fort and threatened to shoot anyone who entered. The crowd scattered, expecting bullets to fly. Captain Biddle stepped in, his pistol at his side, to face Green, who was pointing his gun. He said simply, “Green, if your aim is not good, you are a dead man.”[25]

With that, Green decided that sailing was preferable to death, and was taken to the Andrew Doria along with the others. With these impressments she was now well manned.[26]

On the 13th, three armed schooners arrived from Baltimore, the Wasp, Hornet, and Fly. They were also flying the new flag. As Joshua Barney, the first lieutenant of Hornet, later wrote, “An American flag was sent from Commodore Hopkins for our sloop. I put it on a staff. . . . This was the first time it was seen in the state of Maryland & which I had the honor of carrying.”[27]

Lewes pilots went out to meet them and bring them into the roads. The first American naval fleet was now assembled at Lewes. On Sunday, February 17, Commodore Esek Hopkins noted that the weather was turning bad, “wind out of the N.E. which made it unsafe to lye there. The wind after we got out began to blow hard.”[28] John Paul Jones reported “a sharp northeast wind.”[29]

The townsfolk of Lewes, hearing the fleet was to sail, collected on the Great Dune of the Atlantic beach. Not used to seeing such an array of vessels sail together, they found them a memorable sight as the ships reached the sea. The masts of the square-riggers seemed to touch the heavens, the fore and aft rigged schooners easily kept up with them. Gradually, they shrank in size . . . slipping over the horizon.[30] “The pilot[s] left them about three leagues from False Cape. Steering to the Southward.”[31]

That one week of seeing impressive warships and naval officers in action may well have awakened Jacob Jones’s young mind to ships, men, the sea and war. It was just the first week of many to come. For the next nine years he lived in Lewes and on many occasions witnessed arriving ships being pursued and attacked by the blockading British ships, heard the small arms fire between foraging parties and the militia. He lived under the possibility of threat by invasion from the sea. He watched ships sail to war, heard of the victories of John Barry, John Paul Jones, Lambert Wickes, and others and saw their prizes stop for pilots on the way to Philadelphia. He saw the huge British fleet carrying the army as it stopped off Lewes on its way to capture Philadelphia. He heard the sounds of the naval battle that consolidated that occupation. He could not have missed Joshua Barney’s brilliant maneuvering to win the battle of the Capes at the end of the war.

From all that and more, what boy would fail to form a dream and ambition to go to sea with the navy? Is it any wonder that when the United States Navy needed men, Jacob Jones was among the first to go? As the author of the best short personal biography of Jones wrote, “Whatever reasoning led to his goals . . . Jacob Jones did find his place in newly independent America and its pantheon.[32]

[1]John Middleton Clayton, Address on the Life, Character and Services of Com. Jacob Jones delivered in Wilmington, December 17, 1850 (Wilmington, DE: 1851), 5. Emphasis added. There are only several sentences of primary source information on Jones’s boyhood in one contemporary (1813) article.

[2]Fletcher Pratt, “A Delaware Squire: Jacob Jones,” Preble’s Boys (New York: William Sloan Assoc, 1950), 67.

[3]Jones’s first wife died childless before he entered the navy. He remarried (his second wife’s name has not been recorded) and had a son, Richard A. Jones, who became a captain in the US Navy, and daughter. He married a third time to Ruth Lusby after the death of his second wife and had four children, two of whom reached adulthood, including Edward Stanislius Jones, who became a lieutenant in the US Marine Corps and was with Commodore Matthew Perry during his expedition to Japan. Ronald Ringwalt, “Commodore Jacob Jones, Read before the Historical Society of Delaware March 20, 1906,” Papers of the Historical Society of Delaware, 44 (Wilmington, DE: Historical Society of Delaware, 1906), 6.

[4]Study of property deeds show that Lewes was laid out with lots 60 feet wide along Front, Second and Third Streets and 200 feet deep from Front to Second and from Second to Third. Thus, from Mulberry to Market Street there were five 60 foot lots for 300 feet or 100 yards.

[5]“At 10 A M Cast off from the Piers in Company with all the Fleet.” “Journal of Andria Doria, Feby 11,” Naval Documents of the American Revolution 3: 1219 (NDAR). Presumably the fleet left on the morning ebb tide with the flagship Alfred in the van.The current at Reedy Point is two to three knots at maximum ebb but diminishes further down (today). It is fifty nautical miles from Reedy Point to Lewes. Presumably the fleet sailed with, at least, winds light and variable, or four to six knots. The ships would have made seven to eight knots for a six to seven hour trip. The flagship arriving at about 4 pm and the remainder arriving over the next hour.

[6]These were strong timber poles secured to the bottom by a framework filled with rocks. They protruded at an angle upwards to just beneath the surface of the bay. They were capped with sharp metal tips that could pierce the hull of any unwitting ship. They would have to be removed or destroyed by an approaching enemy squadron while under fire from the fort and the galleys of the Pennsylvania Navy. Samuel Hazard, et. al. ed., Pennsylvania Archives Series 2, Vol. l (Harrisburg, PA: Lane S. Hart, State Printer, 1879), 230-231.

[7]“Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety,” [Philadelphia] Oct. 11th [1775], NDAR2: 405. It lists the ten pilots. Only one, Nehemiah Maull, was a Lewes pilot. “Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety,” [Philadelphia] November 7 [1775], NDAR2: 919. See also “Rules for the Government of Pilots Authorized to Conduct Vessels between the Port of Philadelphia and Chester,” Robert Morris, September 22, 1775, in “The Committee of Safety 1775-1776. The Council of Safety 1776-1777,” Pennsylvania Archives Series 4, 3: 591.

[8]“Pennsylvania Committee of Safety to George Bryan Port Naval Officer,” Philadelphia, June 20, 1775, NDAR5: 650.

[9]“Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety,” [Philadelphia], September 16, NDAR2: 120-122.

[10]Henry Fisher, &c. to Committee of Safety, February, 11, 1776. Pennsylvania Archives, Series 4, 3: 664. Since the Continental Naval Committee had requested that the ships be taken from Philadelphia to Reedy Island by officers of the Pennsylvania Navy. “Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety,” January 1, 1776, NDAR3: 562. The pilots who brought the ships down must have been the Philadelphia pilots based at Chester.

[11]“Alfred . . . A Ship with a Man head, Yellow painted sides Square and Taunt rigged without quarter Galleries.” “A List of Ships and Vessels Fitted out by the Rebels at Philadelphia to Cruize against the English which were Ready to put to sea on the 12th February 1776,” Report of a British Observer, in NDAR3: 1236. Not all the ships of this fleet were painted that way, but it is the color scheme ultimately adopted by newly constructed ships of the Continental Navy. Alfred was converted at the Wharton and Humphreys shipyard, where it had been built. Her former captain, John Barry, was placed in charge of re-rigging. Joshua Humphreys supervised strengthening the hull, timbers, and bulwarks as well as opening gun ports. Andrew Doria, Cabot, and Columbus received similar conversions by Barry and Humphreys, usually at their former owners’ wharves. The “gun ridge” was a feature first added merchant ships converted to warships to strengthen their sides against the vibration of gunfire. It was later continued on all ships and boats as the “gun wale” or “gunnel.”

[12]Captain Nicholas Biddle wrote to his brother James Biddle that the 14th was “like a summer day” and the evening was “calm.” “Nicholas Biddle to James Biddle, Feb:15, 1776,” NDAR 3: 1307. The winter of 1776 was a “comparative moderate” one. During January in Philadelphia the low was 25 and the high 48. “Pennsylvania Weather Records 1644-1835,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 15, 1 (1891), 115. The ships were able to get underway down river from Philadelphia on January 4, but then a cold snap set in and the river froze solid down to Reedy Island and the ships were stuck there until February 10 when a warm spell with temperatures high enough to melt the solid ice and flows set in. Sunset and twilight fromSpectral Calculator, www.spectralcalc.com/solar_calculator/solar_position.php.

[13]John Rodney was a cousin of Caesar Rodney, one of Delaware’s delegates to the Continental Congress and a signer. He and his wife had twelve children and he chose to remain at home and raise them. In November 1776, he became a member of the Committee of Safety of Sussex County. He also served as military treasurer for the county and was a member of the county’s Committee of Accounts of Military Expenses. In 1780 he became Clerk of the Court for the county. He was a contemporary of Penelope’s mother (Jacob Jones’s step-grandmother) and as neighbors of Ryves and Catherine Holt the families were friends. John was executor of Catherine Holt’s will (Will of Catherine Holt, “All Delaware Wills and Probate Records, 1676-1971,” Ancestry.com. Search results for Catherine Holt. Original will on pages bottom of 219 to top of 220 (image 425 of 717).) The papers of Ryves Holt are in the collection of Daniel Rodney, John’s son. Daniel F. Wolcott, “Ryves Holt of Lewes, Delaware, 1696-1763,” Delaware History, 7, 1 (March 1958), 12, 32.)

[14]Daniel Rodney (b. 1764) was four years older than Jones but Caleb Rodney (b. 1767) was less than a year older. Daniel was governor of Delaware from 1814 to 1817 and Caleb was governor from 1822 to 1823, succeeding from Speaker of the House upon the death of the previous governor. Roger A. Martin, History of Delaware Through Its Governors (Dover, DE: Delaware Heritage Commission, 2018). There was only one grammar school in Lewes. It was at the end of Second Street on Shipcarpenter Street, founded in 1761 by a group including Ryves Holt. Only there could Jones have become “well acquainted with the general branches of an English education.” “Captain Jacob Jones,” The Analectic Magazine, 2, (July to December 1813), 71. It is assumed the Rodney boys also went there. Hazel D. Brittingham, “Education in Lewes: 1663-1969,” Lewes History Vol. Xll (November 2009), 5-6. In doing so, from their home they would have walked right by Jones’s house.

[15]“Lt. John Paul Jones raised first American flag over U.S. vessel,” Naval History Blog, U.S. Naval Institute, www.navalhistory.org/2013/12/03/lt-john-paul-jones-raised-1st-american-flag-over-u-s-vessel.

[16]“Serving Lewes with a general store and its harbor as ship chandlers, the Dodd family occupied this site from the latter part of the 18th Century.” “Dodds Corner, History Marker” on Second Street, Lewes, www.historicalmarkerproject.com/markers/HMOSR_dodds-corner_Lewes-DE.html.

[17]The Lewes Independent Company of Foot formed under Capt. David Hall was still in its home-grown clothing. It was just beginning to be formed and would not get full uniforms until Col. John Haslet visited a few months later and began preparing for it to be called to Continental service.

[18]Daniel Rodney must have been inspired. Within a few years he had his own boat and was on the bay harassing British foraging parties. He later served as a local merchant captain before entering business and then politics.

[19]John Paul Jones (original name “John Paul”) “. . . was only around 5-feet-5-inches tall, so small that Abigail [Adams] would ‘sooner think of wrapping him up in cotton wool and putting him into my pocket, than sending him to contend with Cannon Ball.’” “Abigail also concluded that he was ‘Bold enterprizing ambitious and active.’” Cassandra Good, “John Paul Jones and His Romantic Romp Through Paris,” Smithsonian Magazine, April 21, 2015, Smithsonian.com, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/john-paul-jones-and-his-romantic-romp-through-paris-180955059.

[20]“List of Names Run from on Board the Brigantine Andrew Doria, to Which is appended a list of those signed on since 4 January,” NDAR3: 1291-1292.

[21]“Petition of William Green,” December 19, 1775, NDAR3: 172. “Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety,” December 19, 1775, NDAR, 3: 173.

[22]“List of Names Run . . ..”

[23]Boaze Manlove held the elected position of Sheriff of Sussex County from 1770 to 1771 and again from 1773 to 1776. “Sheriff History,” Sussex County Delaware, sussexcountyde.gov/sheriff-history. He was a leading Tory and defected to the British man-of war HMS Preston off Cape Henlopen in March 1777. Harold Hancock, ed., “The Revolutionary War Diary of William Adair,” Delaware History, 13, 2 (October 1968), 158.

[24]“Captain Nicholas Biddle to his sister Mrs. Lydia McFunn,” Letter begins “I was this Morning inform’d that one [William] Green . . ..” NDAR3: 1306-1307n1.While the salutation is missing, the letter was dated February 15, 1776.

[25]Biddle did not tell his sister the dangerous part of the incident. It has been told with various degrees of elaboration in Willis J. Abbot, Bluejackets of 76: A History of the Naval Battles of the American Revolution (New York: Dodd, Mead &Co., 1888), 115. William Bell Clark, Captain Dauntless: The Story of Nicolas Biddle of the Continental Navy (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1949), 98-99. And most recently in Tim McGrath, Give Me a Fast Ship (New York, NY: NAL Calibar, 2014), 39. Tim McGrath, “I Fear Nothing,” Naval History, Vol. 29, no. 4(August 2015), 55-56.

[26]“Nicholas Biddle to James Biddle, Feb: 15, 1776,” NDAR3: 1307.

[27]Autobiography of Joshua Barney,” NDAR3: 1263.

[28]Gardner W. Allen, A Naval History of the American Revolution (New York, NY: Houghton, Mifflin, 1919), 131.

[29]In letter quoted by John Henry Sherbourne, Life and Character of John Paul Jones (New York, NY: Wilder and Campbell, 1825), 12.

[30]McGrath, Fast Ship, 47, citing Pennsylvania Archives, 1st Series, 769–770. Obviously a bit of color added.

[31]“Extract of a Letter from Philadelphia dated 18th March.6,” NDAR, 4: 399.

[32]J. Worth Estes, “A Doctor Goes to Sea,” Delaware History, Vol. XXIV no. 2, 122.

3 Comments

A fascinating story about a man who probably should be better known to fellow citizens.

I did find a LOT of detail in the writing, which should maybe have been a bit less. That young Jones was impressed because of where he lived is an important part of his life, and therefore read and appreciated.

I found it interesting that very little detail about his famous Naval encounter was provided. Having come from a Naval family, and growing up with tradition and lore, I had heard of this Captain Jones, but not many have. A bit more about his famous battle might not have been amiss in this article. Thanks for writing it, and helping understand why Jones left his successful medical practice for the life on the sea. It captured me long ago as well.

Why is Commodore Thomas MacDonough’s defeat of the British fleet on Lake Champlain in September, 1814 left out?

In response to commentors. First of all. thank you for your interest and comments.

To Craig Wilcox. To fit with the Revolutionary War focus and the word limits of JAR articles, this article was originally titled “One Week in the Life of a Boy in the Revolutionary War.” You may be pleased to know that I have published articles on Jacob Jones for the naval Historical foundation. I am working on a book of Jones life. Material forming the the first third of the book will be published this winter locally by the Lewes Historical Society of Delaware. The reason is that it will coincide with the development of a Jones Museum in his boyhood home which is the oldest house in Delaware on its original foundations (1665) and part of the First State national Historic Park. Also see my final comment below.

To Raymond Saint Pierre. I have written articles and given many lectures on Thomas Macdonough and worked with Thomas Macdonough IV to have the Commodore inducted into the Delaware Maritime Hall of Fame. Unfortunately, he did not fit into this article,

Finally, re the editors added en 3 to the article. The arrcurate information is

Jones first wife was Ann Sykes of Dover. She may have died in childbirth.

Jacob Jones second wife was Janet (nee Moore). She was the daughter of Thomas W. Moore and niece of Ann (nee Moore) Ridgely, They were the children of Judge William Moore of Moore Hall near Valley Forge, PA. He was a “hot tempered Tory” and sent Thomas to England rather than see him in Continental service.

After the Revolution, Thomas was sent to Newport, RI as British Consul and his wife and daughter Janet followed him.

Janet was on a coach from Philadelphia to Dover, DE to visit her aunt Ann Ridgely when she and Jacob met. A romance followed which the aunt tried to control but failed. Thomas readily agreed to the marriage but he and wife did not attend. Jacob and Janet had a first child William while in Dover.

After Jones joined the navy in 1799, Janet lived with her mother and an aunt on her mother’s side and a half-sister in Brooklyn, NY. William died during that period. Jones visited on shore leave and they had three more children, 1800-1804. (daughter was named Williamina, there was a son, Please provide the source of Richard A. Jones USN and another that cannot be verified.)

Janet died of “consumption” in 1805 while Jones was in captivity in Tripoli. The children were first cared for by the half-sister and neighbors until Jones returned. It was said he “dispersed” them?

All of the above, and much more about the personality of Jones can be found in Mabel Lloyd Ridgely, What Them Befell: The Ridgelys of Delaware and Their Circle: In Colonial and Federal Times: Letters 1751-1890 (Portland, MA: Anthoensen Press, 1948).

The letters between Ann Ridgely and her brother Thomas Moore aboat the romance and marriage and between Janet and aunt Ann and cousin Williamina Ridgely, about life in Brooklyn, and the final letter from Janet’s half-sister Ann Sands to Williamina Ridgely telling of Janet’s death and subsequent issues are pages 135-156.

William Manthorpe