By the end of 1774, Catharine Macaulay had met Benjamin Rush, Arthur Lee, Richard Marchant, and Benjamin Franklin, and had corresponded with John Dickinson, James Otis, Jr., John Adams, William Livingston, Richard Henry Lee, Abigail Adams, Ezra Stiles, Mercy Otis Warren, and Samuel Adams. The number of Americans that Macaulay had met was about to change.

On December 30, 1774 Josiah Quincy, Jr., a representative of the colony of Massachusetts and the author of the pamphlet Observations on the Act of Parliament, commonly called the Boston Port Bill, with Thoughts on Civil Society and Standing Armies, visited Bath. He had arrived at Falmouth, England on November 8 but did not reach London until November 17. Between his arrival in London and his arrival in Bath he had met with Charles and Edward Dilly, owners of the New York Coffee Shop, a number of Honest Whigs who gathered there, Lord North (on November 19), former governor of Massachusetts Thomas Pownall (on November 21), Lord Dartmouth (on November 24), Lord Saville (December 5), and Lord Shelburne (on December 12). His mission was to lay out

a clear and full idea of the true situation of political affairs . . . in consequence of the late acts of the British Parliament” and “have the opportunity of conversing with those, in and out of administration, who may have been led into wrong sentiments of the people of Boston and the Massachusetts Province.[1]

On December 31, Quincy “visited the celebrated Mrs. Macaulay: delivered my letters to her, and was favoured with a conversation of about an hour and a half, in which I was much pleased with her good sense and liberal turn of mind. She is indeed an extraordinary woman.”[2] On January 2, he again “spent the afternoon in very improving conversation with Mrs. Macaulay.”[3]

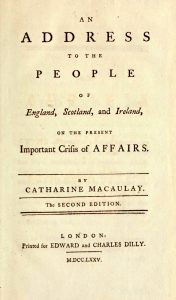

Two weeks later, Macaulay published her An Address To the People of England, Scotland, and Ireland On the Present Important Crisis of Affairs. Concerned that the situation between Britain and the colonies had “grown very alarming,”[4] she appealed for a change in government policy. Her argument began with the following:

My friends and fellow citizens . . . the ministry, after having exhausted all those ample sources of corruption which your own tameness under oppressive taxes have afforded, either fearing the unbiased judgment of the people, or impatient at the slow, but steady progress of despotism, have attempted to wrest from our American Colonists every privilege necessary to freeman . . .

She then presented examples of how the privileges have been wrested:

[We] have seen the Americans . . . stripped of the most valuable of their rights; and, to the eternal shame of this country, the stamp act, by which they were taxed in an arbitrary manner, met with no opposition, except from those who are particularly concerned, that the commercial intercourse . . . should meet with no interruption . . . With the same guilty acquiescence, you have seen the last Parliament finish their venal course, with passing two acts for shutting up the Port of Boston, for indemnifying the murderers of the inhabitants of Massachusetts-Bay, and changing their chartered constitution of government . . . and, without any interruption either of petition or remonstrance, [have] passed another act for changing the government of Quebec . . .

Next, she identified those who purposely misinformed the English people of the effects of the Acts and why:

In these times of general discontent, when almost every act of our Governors excites a jealousy and apprehension in all those who make the interests of the community their care, there are several amongst us who, dazzled with the sun-shine of a court, or fattening on the spoils of the people, have used their utmost endeavours to darken your understandings on these subjects, which, at this time it is particularly your business to be acquainted with . . . [The Ministers and Members of Parliament assert] that you are too needy and too ignorant to be adequate judges of your own business . . . [They] have had the insolence to tell you . . . that all goes well, that your Governors faithfully fulfil the duties of their office, and that there are no grievances worthy to be complained of but those which arise from that spirit of faction . . .

Macaulay then offered a means of restoring the bond between Great Britain and her colonies:

A conquered city has time given it to raise the contributions laid upon it, and may raise it in its own way. We have treated our Colonies worse than conquered enemies. Neither Wales nor Ireland are taxed unheard and unrepresented in the British Parliament; as the Colonies [are] . . . My friends and fellow citizens, the Americans declare, that if you will not oppress them . . . they will ever esteem a union with you . . . they will be ever ready to contribute all in their power towards the welfare of the empire; and that they will . . . hold your interests as dear to them as their own . . .

She concluded the Address as if speaking passionately on the floor of the Roman Senate:

[The colonists] exhort you, my friends and fellow citizens, for the sake of that honour and justice for which this nation was once renowned—they entreat you . . . not to suffer your enemies to effect your slavery in their ruin.

If a civil war commences between Great-Britain and her Colonies, either the Mother Country, by one great exertion, may ruin both herself and America, or the Americans, by a lingering contest, will gain an independency; and in this case, all those advantages which you for some time have enjoyed by your Colonies, and which have hitherto preserved you from a national bankruptcy, must for ever have an end; and whilst a new, a flourishing, and an extensive empire of freemen is established on the other side [of] the Atlantic, you, with the loss of all those blessings you have received by the unrivalled state of your commerce, will be left to the bare possession of your foggy islands; and this under the sway of a domestic despot, or . . . an easy prey to the courts of France and Spain.

Rouse, my countrymen! Rouse from that state of guilty dissipation in which you have too long remained, and in which, if you longer continue, you are lost forever. Rouse! and unite in one general effort; ‘till by your unanimous and repeated Addresses to the Throne, and to both Houses of Parliament, you draw the attention of every part of the government to their own interests, and to the dangerous state of the British empire.[5]

Macaulay could have entitled her work, “A Dark Cloud which Hangs over the Empire.” What made the address extraordinary were the following:

- She addressed colloquially and directly the people of Britain instead of the King or Parliament

- She called out the corrupt royal appointees in the colonies

- She called out the Ministry’s disrespect and disregard for the political judgments of the British people

- She offered two outcomes to the impending civil war, neither of which was good for Britain

- She ended her work with a dire warning

In 1769, Macaulay had sold the copyrights to all four volumes of her History of England from the Accession of James I to that of the Brunswick Line to the London printers Edward and Charles Dilly, and agreed to allow them to publish all of her future writings. On January 13, the day that the Dillys printed the Address To the People of England, Scotland, and Ireland On the Present Important Crisis of Affairs they sent four copies of the “small pamphlet published this Day by Mrs. Macauly” to John Adams.[6]

One week later, Macaulay wrote to Mr. and Mrs. Northcote, friends whom she had recently stayed with for three months in Devonshire south of Bath.

In the declining, fallen state of England to hear our children as the Americans are called breathing sentiments which would have done honour to our country in its most virtuous, its more vigorous days, must fill with great satisfactions every Englishman’s breast untainted with the vices of the age. [Because of] my unabated zeal for the welfare, the prosperity, and the liberties of the British Empire more than from my prospect of success in this profligate state of public conduct I have drawn up an Address to my Countrymen on the present important crisis of Affairs.[7]

On February 25, Abigail Adams received a letter from Mercy Otis Warren inquiring whether “the letters to Mrs. Macaulay are gone.” The packet of letters she was referring to included Abigail’s letter to Macaulay dated “1774.” Warren was hoping to include a letter dated December 29, 1774 that she had just finished, but it was too late. The ship carrying the packet had already departed for England.

[My letter] is Rather more lengthy than I should have presumed [it] to have been . . . but I thought the Circumstances of America were such that it demanded some perticulars from Every hand, more Especially as we have so Many Busy and Mischievious tongues and Pens to Vilify and misrepresent us.[8]

By this time Macaulay had become a celebrity in Bath. She hosted dinner parties, entertained visitors and periodically would “give lessons on general politics and English constitutional history.”[9] She renewed old friendships with Vicar Augustus Toplady of Broad-Hembury, Mr. and Mrs. Northcote, his neighbors, and John Wilkes, the political dissident former Member of Parliament and current Lord Mayor of London, and developed new friendships with Dr. Clement Cruttwell, his brother and printer Richard Cruttwell, artist Joseph Wright, writer Edmund Rack, physician (with questionable credentials) Dr. James Graham, clergyman Richard Polwhele, Toplady’s friend John Collett Ryland, and poet and playwright Hannah More. Of all of her friends in Bath, the one who unquestionably doted upon her was Rev. Dr. Thomas Wilson. He was the non-resident rector of St. Stephen’s-Walbrook in London, the prebendary of Westminster, and a founding member of the Society of the Supporters of the Bill of Rights through which he became a close friend of John Wilkes and an acquaintance of Macaulay’s brother John. Following the death of his wife in 1772, he moved to Bath and made “his permanent home at Alfred House No. 2.”[10] In addition to his high level of education, he was a philanthropist and the owner of an extensive library. It is unclear whether he met Macaulay prior to her arrival in Bath, but he had read all five volumes of her History. He quickly became taken with Macaulay’s intelligence, genteel manner, conversational wit, and political dispositions.

Macaulay received four letters over the next ten months. Even though one was formally addressed to Edward Dilly, it was equally intended for Macaulay. On April 15, 1775, four days before the confrontations at Lexington and Concord, Dr Ezra Stiles wrote to Macaulay,

The Resolutions of Parliament instead of intimidating only add Fuel to the Flame, invigorate & strengthen the Resolutions of the Americans . . .We hoped the unhappy & unnatural Differences would have been amicably adjusted upon Principles of Public Justice, Equity, [and] Benevolence. If otherwise, America is ready for the last Appeal, which however shocking and tremendous, is by the Body of the Colonies judged less terrible than the Depredations of Tyranny & arbitrary Power . . . It will not be the Loss of several Battles that can conquer & subdue the Spirit of a hardy People fighting for Property, Religion & Liberty . . . Our fathers fled hither for Religion and Liberty; if extirpated from hence, we have no new World to flee to. God has located us here, and by this Location has commanded us here to make a Stand . . . It is my ardent Prayer to the Most High that the Union between Great Britain and these Colonies may never be dissolved; and that we may always boast and glory in having Great Britain the Head of the whole British Empire. And we thank you, dear Madam, for interposing your kind Offices, in your late truly patriotic . . . Address to the three Kingdoms.[11]

On May 22, Abigail Adams wrote to Edward Dilly on behalf of her husband, John, who had recently set off for Philadelphia and the Second Continental Congress.

The state of the inhabitants of the town of Boston and their distresses no language can paint—imprisoned with the Enemies, suffering hunger and famine, obliged to ensure Insults and abuses from breach of faith lited to them in the most solemn manner by the General, that if they would deliver up their arms, both they and their affects should be suffered to depart, and then treacherously deceived—for no sooner did they comply , but he said merchandize was not considerd as affects . . . Very few [women] but have husbands, Brothers or Sons [because] each[was] jeopardizing their lives in their Defence . . . the British troops who have been landing upon one of our Sea coasts . . . [have been] plundering hay and cattle . . . We have lamented the infatuation of Britain and have wished an hounourable reconsiliation with till she has plunged her Sword into our Bosoms . . . Tyranny, oppression and Murder have been the reward of all the affection, the veneration and the loyalty which has heretofore distinguished Americans . . . [then came ] the terrible 19 of April when they premeditately went forth and secretly fell upon our people like savage furies . . . Tis thought we must now bid a final adieu to Britain, nothing will now appease the Exasperated Americans but the heads of those traitors who have subverted the constitution, for the blood of our Breathren crys to us from the Ground.[12]

Abigail also included with the letter a number of papers written by John under the pen name Novanglus.

On August 24, Mercy Otis Warren wrote to Macaulay,

The public papers as well as private accounts have Witnessed to the Bravery of the Peasants of Lexington, the spirit of Freedom breath’d from the Inhabitants of the surrounding Villages . . . the Conflagration of Charlestown will undoubtedly Reach Each British Ear before this comes to your Hand. Such Instances of Wanton Barbarity have been seldom practiced Even among the Most Rude & uncivilized Nations . . . I shall give a short Account of the present situation of American affairs in the environs of Boston. We have a well Appointed Brave & High spirited Continental Army, Consisting of About twenty-two thousand Men, Commanded by the Accomplished George Washington Eqr . . . This army is to . . . be supported & paid at the Expence of the United Colonies of America . . . Both the Ministerial & the American armies seem at present to be Rather on the Defensive as if Each were wishing for some Benign Hand to Interpass & heal the Dreadful Contest without letting out the Blood from the Bosom of their Brethren . . . so tenacious are we of the Birth Rights of Nature & the fair possession of freedom which no power on Earth has a Right to Curtail that we shall Never give up the Invaluable Claim . . .[13]

On November 29, 1775, Macaulay received a letter from Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, a delegate to the Congress, saying, “North America is not fallen, nor likely to fall down before the Images that the King hath set up . . . Lexington, Concord, and Bunkers Hill opened the tragic scene.” He went on to describe the taking of Fort Chambly, St. Johns, and eventually Montreal. Unfortunately, he assumed another victory that would not come to pass:

It was expected that [Gen. Carleton] would fall into the hands of Colo. Arnold, then at Quebec, to which place he had penetrated with 1000 men by the rivers Kenebec and Chaudiere. No doubt is entertained here, but that this Congress will be shortly joined by Delegates from Canada, which will then complete the union of 14 Provinces . . . the Councils of America [have determined] to prepare for defence with the utmost vigor both by Sea & land, Altho’ upon the former of these elements, America may not at first be in condition to meet the force of G. Britain . . . time and attention will, under the fostering hand of Liberty, make great changes [in] this matter. The knowing ones are of opinion that by next Spring so many Armed Vessels will be fitted out as to annoy our enemies greatly.[14]

This was the last letter Macaulay would receive from the colonies until February 1777 when she secretly received three letters from Mercy Otis Warren.

During 1774, Macaulay and Edward Dilly believed her mail was being tampered with. To protect Macaulay and her correspondence, Dilly took a series of steps: first, in the spring of 1774, he asked that all letters sent from Massachusetts henceforth “for Mrs. Macaulay [be sent] . . . under Cover, to me;” second, in the fall, that all letters henceforth be transported by trusted captains, including Scott, Gordon, Faulkner or Falconer; and third, in the winter of 1774 and spring of 1775, that all letters from him to Massachusetts henceforth would be sent “To the Care of my friend, Mr. Henry Bromfield of Boston.” The system seemed to work until the War broke out and “all freedom of intercourse [was] now cut-off;—cut off not only by Royal Proclamation, but necessarily impeded by the hostile movements between Great Britain and a country which has been long used to look over to her with warm affection as a friend, protector, and parent.”[15]

On August 23, 1775, King George III issued the Proclamation for Suppressing Rebellion and Sedition. It was in this document that he pronounced the colonies “have at length proceeded to open and avowed rebellion.” It was also in this document that he suspended the Act of Habeas Corpus.

We strictly charge and command all our Officers, civil as well military [and] our obedient and loyal subjects . . . to disclose and make known all treasons and traitorous conspiracies which they shall know to be against us . . . and transmit . . . due and full information of all persons who shall be found carrying on correspondence with, or in any manner of degree aiding or abetting the persons now in open arms and rebellion against our Government within any of our Colonies.[16]

Because of her criticism of the government, her pro-American sympathies, and her correspondence with a number of the American revolutionaries, Macaulay’s friends became concerned for her safety. She now had not only her health to worry about but also the possible loss of her freedom.

Note: Be sure to read about Catharine Macaulay, 1763 thru 1772, and Catharine Macaulay in 1773 and 1774.

[1]Eliza Susan Quincy, ed., Memoir of the Life of Josiah Quincy Adams, Junior of Massachusetts Bay: 1774-1775 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1875), 159.

[4]Catharine Macaulay to Henry Marchant, October 1774,” in Edward Field, ed., State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations at the End of the Century: A History (Boston and Syracuse, NY: Mason Publishing Company, 1902), 224.

[5]Catharine Macaulay, An Address To the People of England, Scotland, and Ireland On the Present Important Crisis of Affairs (London: Edward and Charles Dilly, 1775), 3-29.

[6]Thomas Belsham, Memoirs of the late Reverend Theophilus Lindsey, 2nd edition (London: 1820), 391; Edward Dilly, to John Adams, January 13, 1775, in The Adams Papers, Papers of John Adams, December 1773—April 1775, Robert J. Taylor, ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1777), 2: 211-13.

[7]www.gilderlehrman.org/collection/glc017943.

[8]Mercy Otis Warren to Abigail Adams, February 25, 1775,” in The Adams Papers, Adams Family Correspondence, December 1761—May 1776, Lyman H. Butterfield, ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963), 1: 186-88.

[9]Rev. Joseph Hunter, The Connection of Bath with the Literature and Science of England(1853), 56-7.

[10]C.L.S. Linnell, ed., The Diaries of Thomas Wilson D.D. (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1964), 17.

[11]www.gilderlehrman.org/collection/glc01798.

[12]Abigail Adams to Dilly, May 22, 1775,” in The Adams Papers, December 1761—May 1776,1: 200-04.

[13]www.gilderlehrman.org/collection/glc0180002.

[14]James Curtis Ballagh, The Letters of Richard Henry Lee, 1762-1778 (National Society of the Colonial Dames of America, 1911), 1: 160-64.

[15]Jeffrey H. Richards and Sharon M. Harris, eds., Mercy Otis Warren: Selected Letters (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2009), 84-5.

[16]Proclamation for Suppressing Rebellion and Sedition (London: Charles Eyre and William Strahan, 1775).

Recent Articles

This Week on Dispatches: Scott Syfert on the Mecklenburg Declaration

Richard Cranch, Boston Colonial Watchmaker

Announcing the 2025 JAR Book of the Year Award!

Recent Comments

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

I am not sure I will ever be convincingly swayed one way...

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

Interesting! Thanks, from a Charlotte NC Am Rev fan.

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

A great overview of that controversial document. I tend not to accept...