In 1782, when the sixteen-gun sloop-of-war HMS Albany was determined to be at the end of her usefulness, nobody seemed truly surprised or sad about it, least of all her commander. The vessel had survived six continuous years of war-time service in His Majesty’s Royal Navy, in addition to a prior life as a merchant vessel. She had done patrol duty, convoy duty, seized ships and smugglers, and battled warships from Massachusetts. Now she was considered old and decrepit. Her captain had long been frustrated with his command of her and often referred to her as that “wretched” ship, but that was due more to frustration with his lack of advancement than the vessel’s overall fitness. Her end was ignominious, a decrepit prisoner-of-war transport vessel shipwrecked on partially submerged rocks during a fierce New England storm in December 1782. The event was barely noted or remarked upon, fitting perhaps since throughout her service life, Albany and her commander had frequently been short-changed the credit or honor due to them. The vessel’s history and service, however, actually merits more glory and laurels than her end suggests.

The origins of Albany are not quite clear. One source states she began as the American sloop Howe, built and launched in New York. The New England Chronicle in September 12, 1776, reported the vessel as the former Rittenhouse from Philadelphia. Molyneux Shuldham, vice admiral of the blue and commander-in-chief of His Britannic Majesty’s Ships in North America from January to July 1776, referred to Albany as the former Britannia. Ship captain Hector McNeill, later of the Continental Navy, owned several vessels including a sloop named Brittania. It is possible Albany had been his ship, which he offered for sale in 1776. Having plied New England waters, Brittania had likely become familiar to Royal Navy Capt. Henry Mowatt.[1]

Henry Mowatt (some sources spell it Mowat) had been on the American station as surveyor and naval officer since 1758 and probably knew more about the Maine coast than anyone else in the service. He had over a decade of hydrographic surveying experience aboard the Canceaux, at which time he also chased and captured smugglers. But in the fall of 1775, his name became synonymous with the devil. On October 18, he commanded a small British naval force that arrived off Falmouth, present-day Portland, Maine. Mowatt carried orders to bombard the town, which he proceeded to do, after alerting the townspeople and giving them time to leave their homes. The subsequent burning of Falmouth made him a hated man along the New England coast. It also appears to have stymied his career advancement. In January 1776, he sailed back to Portsmouth, England for his old survey ship Canceaux to be refitted. It was in England, while awaiting command of a frigate or something better, that Mowatt recommended for purchase into the navy a ship currently in Boston that would be re-named Albany.[2]

The Lord Commissioners wrote to Vice Admiral Shuldham that Mowatt

hath represented to us that there is at Boston a Merchant ship called the Brittania which has been surveyed by your order, in dimensions as far as he can recollect . . . judged capable of carrying sixteen six Pounder with Swivels . . . You are hereby required and directed, so soon after the receipt hereof as possible, to purchase the said Ship upon the most advantageous terms you can for His Majesty, and to call her by the name of the Albany accordingly; directing the Naval Officer at Boston to pay for the purchase of her.[3]

In the meantime, events dictated otherwise. In March, Boston had been evacuated of 9,000 British soldiers and more than 1,000 Loyalists. They had boarded 120 ships in Boston Harbor on St. Patrick’s Day morning, in what has since become the public holiday known as Evacuation Day. After being out-maneuvered by George Washington’s guns installed atop Dorchester Heights, the British had decided to vacate the town. The enormous flotilla set sail for Nova Scotia. It was Washington’s first military victory as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. The vessel Mowatt had recommended for purchase was likely used in this massive evacuation and then afterwards sat in the harbor at Halifax, Nova Scotia.[4]

Although he wanted to remain in England to await a better command, Mowatt was ordered back to America. He and a party of Loyalists left London on April 4, 1776 and by the end of the month, Canceaux cleared Yarmouth on its way back to America. After his arrival in Halifax, Mowatt took command that June of the newly purchased Albany. He had not expected to command the vessel and was disappointed in the posting. The experienced officer considered her sea-worthy and had suggested her purchase, but considered the vessel to be in poor shape. He had hoped for something better. With her purchase and commission, HMS Albany became part of the large naval armada Lord North’s ministry put into the waters of North America to quell the growing rebellion. Her new home station was Halifax and the naval yard quickly converted her to a Royal Navy vessel armed with sixteen cannon.[5]

Albany was one hundred feet long, twenty-six feet in beam, and about 230 tons. She had a wooden hull, plenty of sail and carried a 125-man crew. But her draft was shallow and her officer accommodations considered poor. Mowatt thought her capable of service but a “wretched” ship. The vessel became part of the Nova Scotia station, sent out to protect British shipping and capture rebel vessels.[6]

On November 18, 1776, Albany dispatched one of her boats to take a sloop named Providence, loaded with lime and cord wood. The rebel vessel had tried to enter a harbor known as Herring Gut, near present-day Port Clyde, Maine. When Albany’s boat approached, the crew deserted the ship. No papers were found by the searchers from Albany.[7]

Throughout 1777, the sloop patrolled the sea lanes of New England and the Canadian Maritimes, doing convoy duty and seizing rebel vessels. Mowatt grew increasingly dissatisfied with his position on the periphery of the war. After six months aboard Albany, he took brief command of HMS Milford and then HMS Scarborough. In those ships he fought some daring sea battles, including a few engagements against American captain John Paul Jones. In May 1777, when ordered to return to Albany, he felt his capabilities as a captain had been insulted. One bright spot was the arrival of his surrogate son, Robert Percy. In May, the young man transferred to Mowat’s command aboard Albany and continued to serve his patron throughout the entire Revolutionary War period.[8]

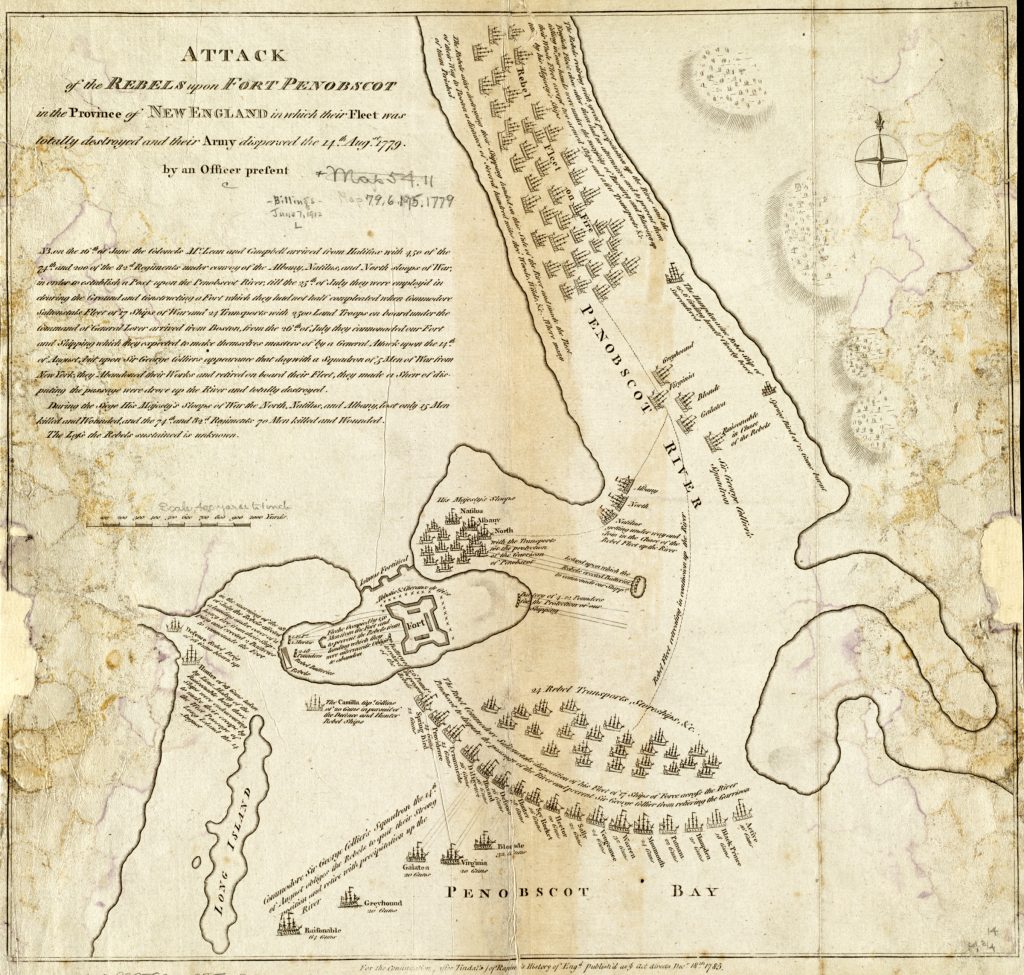

Likely due to the destruction of Falmouth, Mowatt’s career languished and for the next five years he remained commander of Albany. Much to his frustration, the sloop mostly guarded Canadian waters from rebel fishermen.[9] Even his commendable service in defense of Fort George in Castine, Maine, against the Penobscot Expedition in 1779 could not dispel the cloud over his lack of advancement.

When the British decided to occupy a large part of downeast Maine late in the war, the Albany and Mowatt, with his intimate knowledge of the coast, were considered crucial to the objective. One source states Albany was called to New York at the beginning of 1779 to name Mowatt as commander of the naval part of the force. This did not materialize and Mowatt and Albany were ordered back to Halifax with a load of powder to replenish the garrison there. At Halifax, Sir George Collier ordered Mowatt and Albany to the Bay of Fundy and then himself soon departed for New York. Mowatt countered, in a letter from Bay of Fundy, stating Albany was not sufficient a class of ship to lead the invasion force. But the letter garnered no response and orders arrived for Albany to report back to Halifax. There, Mowatt arrived as the invasion force readied to depart. Capt. Andrew Barclay of the frigate Blonde happened to be in Halifax and Mowatt urged Vice Admiral James Gabbier to have Blonde at least accompany Mowatt’s small force. The admiral agreed, but Mowatt still had to lead the invasion force from aboard the “wretched” Albany.[10]

The force sailed for Penobscot in early June. Albany, accompanied by the sloops North and Nautilus, convoyed four armed troop transports to the Bagaduce peninsula, present-day Castine, Maine, in the heart of Penobscot Bay. One transport was London, commanded by Henry Mowatt’s brother David. The frigate Blonde sailed nearby, at one point scaring off a pesky rebel group of ships.[11]

They arrived on June 17, 1779 and landed 750 men under command of Brig. Gen. Francis McLean. In addition to construction engineers and artillerymen, McLean brought 450 Argyle Highlanders from 74th Foot regiment and 200 men from 82nd Foot, a force totaling roughly 700 men. A site was chosen on the center high ground of the peninsula, one that gave commanding views of the harbor and approaches.[12]

Construction immediately began on a large fort, called Fort George in honor of their sovereign. To Mowatt’s frustration, the Blonde soon departed, which left only Albany and sloops North and Nautilus to defend the new post. Mowatt commanded Albany while Jerrard Selby led the sixteen-gun North and Lt. Thomas Farnham commanded the sixteen-gun Nautilus.[13] Long familiar with New Englanders, Henry Mowatt knew they would soon mount a counter-attack.

In late July, just before Americans attacked the Bagaduce post, Mowatt and Albany captured the sloop Sally in Penobscot Bay. They found her with no one on board but loaded with cordwood. Richard Pomroy of Albany described Sally as a typical plantation-built sloop with a square stern, no head and an all-black bottom and sides. He had sailed on her in Casco Bay seven years earlier, at which time she had belonged to a John Gray.[14]

The anticipated American counter-attack arrived in the form of eighteen warships and twenty-four transports, mostly from Massachusetts and New Hampshire. Led by Commodore Dudley Saltonstall, the ships landed armed forces under command of Gen. Solomon Lovell to dislodge the British from Fort George. Paul Revere was in command of the artillery. Delays, miscommunication and squabbles soon overtook the American forces which allowed Mowatt time to expertly position Albany, Nautilus and North in defense of the small harbor and approach to Fort George. He “sprung” the three sloops, a nautical term to align vessels end to end across the mouth of Castine’s harbor. The tactic was sound; any approaching American ships faced a three ship broadside of cannon fire. Mowatt also allowed use of some of his sloops’ cannon for shore batteries and seconded as many sailors as possible to help with the fort’s defenses.[15]

When the British first arrived at Penobscot, they had arranged for Thomas Goldthwaite, former commander of nearby Fort Pownal then living in its ruins with his family, to come to Castine. This may have been an opportunity to seek British protection at Fort George. Before the arrival of enemy forces, Goldthwaite and his family, including son-in-law Francis Archibald, were quartered aboard Albany, on board which Goldthwaite’s son Henry had taken refuge on July 23. On July 25 the enemy arrival forced the Goldthwaite family to be moved off the ship to a house and barn far from shore, which became a military hospital and social center for many who tended to congregate there in evenings.[16]

With a relief squadron, Admiral Sir George Collier, suffering so much from a fever he was confined to a chair on his quarter-deck, arrived off Penobscot on evening of August 13. His fleet consisted of the thirty-two-gun Blonde with Capt. Andrew Barkley, twenty-eight-gun Virginia under Capt. John Orde, twenty-eight-gun Greyhound with Capt. Archibald Dickson, twenty-gun Camilla with Capt. John Collins, and twenty-gun Galatea under Capt. John Howorth. The fourteen-gun sloop Otter under Capt. Creyk and Collier’s own flag ship, sixty-four-gun Raisonnable, completed the formidable force.[17]

The next day, Collier arranged his forces in a crescent to do battle. The American fleet, which had re-embarked its land forces throughout the night, instead fled upriver. When Saltonstall and his warships sped past the American transports, it meant everyone had to shift for themselves. The rout which followed saw no escape. Most American vessels were grounded and burned by their own crews, with just one vessel captured by the British. The rest were destroyed in what historians have called the worst American naval defeat up to Pearl Harbor.[18]

With arrival of Collier’s fleet and American retreat, the Albany, North, and Nautilus quickly joined in pursuit of the rebels. Henry, one of Goldthwaite’s sons, aided the British aboard Albany in their chase. He participated until wounded by a musket ball. Henry had difficulty recovering from his wound and eventually sailed for England on December 24, 1781. Mowatt and his flotilla had done more than their share to save the eastern provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland, as well as the numerous Loyalists who now flocked there. Among the latter was Mowatt’s brother David of Kittery.[19]

After this stunning defeat of Massachusetts forces, Henry Mowatt failed to receive any proper recognition for his important role in defense of Fort George. He recognized the battle had been America’s worst blow received during the war. Instead of having the honor of taking the official siege account back to London, Collier snubbed him, with a dubious claim Mowatt and his ship could not be spared. He then ordered Mowatt and Albany upriver to search for cannon from the wrecks. Collier sent word of his victory to London by another vessel. Mowatt wrote, “services of the three sloops of war during the siege were totally omitted and their captains not even named.” For the remainder of his career, Mowatt was regularly blocked, sidelined, or bypassed in most career advancements; often junior officers saw promotion over him. At one point he wrote, “his feelings as a man, his spirit and honor as an officer and his duty to the service, injured and degraded, in his rank compelled him to consider resignation from the service.”[20]

On October 27, 1779 there was a total solar eclipse, important enough that suspension of war was arranged with Henry Mowatt aboard Albany. A scientific team from Harvard, organized by Rev. Samuel Williams and led by science professor Fortescue Vernon, wanted to travel with six students to Long Island, present-day Isleboro, and set up an observation post. Leave for the observers was granted, but with a clear order to have no communication with any inhabitants, and to depart on the 28th, the day after the eclipse.

Being thus retarded and embarrassed by military orders, and allowed no time after the eclipse to make any observations, it became necessary to set up our apparatus and begin our observations without any further loss of time; in the course of which we received every kind of assistance from Capt. Henry Mowatt, of the Albany, which it was in his power to give.[21]

It was the 48th eclipse in Saros series 120, the total duration was two minutes and it made an amazing spectacle for observers in its 138km wide path. Today, a granite marker sits on site of their observations.[22]

The winter of 1779-80 was so cold and brutal, there was widespread starvation. Mowatt, much against the evil caricature of the devil who had burned Falmouth, arranged food and shelter for needy families. In early February 1780, the schooner Good Intent and her master Willmot Wass was captured in Penobscot Bay by Albany. The vessel was later condemned.[23]

In May 1780, Henry Mowatt was aboard Albany in the Bagaduce River. There he provided orders for a Loyalist regiment, the King’s American Rangers. The force was under command of James Ryder Mowatt (it is not clear if he was a family connection or not).

You are hereby impowered and directed to take by Force of Arms, all Vessels and Craft that may fall in your power, belonging to the Subjects of the Kings of France and Spain, as also those belonging to the Rebells of America, and you are to order all Captains to this Port or to some other place in Nova Scotia.[24]

On May 23, the thirty-ton schooner Sukey and her master and owner named Proud was captured about one league eastward off Frenchman’s Island, near mouth of the Damariscotta river. Capt. James Ryder Mowatt of the King’s American Rangers captured her while in command of two boats belonging to Albany. He put two of the prisoners ashore and sent the vessel to Fort George at Castine and then on to Windsor, Nova Scotia.[25]

James Mowatt’s ranger force continued to operate throughout Penobscot Bay seeking vengeance on those who chose not to take the loyalty oath. Henry Mowatt’s brother David appears to have also served in this group, and both he and James Ryder were apparently taken prisoner that June. Although they attempted an escape, they were recaptured near the Isle of Shoals.[26]

On July 5 the sloop Patty, loaded with wood and bark, was captured off Sheepscot River by the Mermaid, tender to Albany. The vessel, owned by David Rudd, was out of Townsend, present-day Boothbay Harbor. As Mermaid approached, Patty’s crew escaped in boats. She was carried into Fort George. Later in October, working in conjunction with Blonde, Nautilus, North, and brig Hope, Henry Mowatt and Albany captured two sloops, Mercury and Fortune. The following March, Albany’s tender Mermaid captured the schooner Nancy. Her master was George Leach and the armed vessel had six swivel guns mounted on carriages. She was sent eastward to Halifax.[27]

At some point in the following years, Albany was involved in the capture of the schooner Ranger and re-capture off Cape Sable of sloop William and Barbara loaded with wine and salt. On June 24, 1782, Halifax courts adjudicated several vessels Albany had captured, seized or forced into port. They included sloops Hannah, Sally, and Tryal. There was also schooner Swallow and schooner Paco Bob. Another vessel taken by Albany had no name. It was a shallop that had been captured and plundered by the Americans. She was carried into Castine.[28]

Henry Mowatt remained senior naval officer in Penobscot aboard the “wretched” Albany. Advancement and better postings eluded him throughout the war’s final years. It was a bitter pill for him to swallow as he saw younger, less experienced officers promoted above him. By July 1782, he apparently had had enough. That year, Albany had been relegated to patrol duty. In July, a survey board declared her unfit for any further Royal Navy service. Without a friend in high places and with no official recognition for his nearly twenty-seven years of active service, Mowatt asked Admiral Robert Digby for permission to return to England. He was ready to resign his commission. Permission to return was granted in the fall of 1782.[29]

It is unclear whether Mowatt was still aboard Albany at this time. It is known he was in Halifax in August 1782 when he penned a letter to Rev. Jacob Bailey in Annapolis about educating his young son. Albany’s master’s logs in the British National Archives end on June 8, 1782. Mowatt may have had nothing more to do with the vessel after she was declared unfit for service that July. But with prisoner of war exchanges between British and Americans increasing in numbers and frequency, Albany still had a job to perform. On October 2, 1782, the vessel was loaded with 232 American prisoners of war at Halifax and sailed to Boston for repatriation. One source states Mowatt was no longer in command of her by then, but another states he and his ward Robert Percy served aboard Albany from June 1776 to October 25, 1782, so it is possible Mowatt made this voyage as her captain. He likely did not think much of this service as commander of a prisoner transport carrier. Regardless, by late October 1782, Mowatt was seriously re-thinking his naval career and ready to go home to England.[30]

Once back in England, he did not resign but instead was finally promoted to captain. His next command was twenty-eight-gun captured French merchant ship La Sophie, but two years later she too was ordered to be sold. Henry Mowatt served in the Royal Navy for forty-four years, thirty of them spent on the North American station mostly in New England waters. He and his brother David had several professional and personal ties with Maine, especially in Castine during its occupation and after. On April 14, 1798 aboard HMS Assistance off the Virginia coast at age sixty-four, Henry Mowatt fell dead from apoplexy. He is buried in St. John’s Episcopal Church graveyard in Hampton, Virginia.[31]

The Albany delivered the prisoners of war to Boston in October 1782. She may have made more trips between Halifax, Castine, and Boston with prisoners in November or December. In December 1782, she was in Boston preparing to depart for Castine and then Halifax. Albany headed toward Castine and Fort George in Penobscot Bay where she wrecked on the Northern Triangles.The vessel by this time had a crew of fewer than sixty men.[32]

The Northern Triangles are an extensive series of rocks and ledges at southern entrance to Penobscot Bay, southwest of Vinal Haven just north of and within sight of Little Green and Large Green Islands. Located halfway between Tennants’ Harbor and Matinicus Island, the triangles are a true ship hazard at low tide in Two Bush Channel.[33]

The HMS Albany was wrecked on December 28, 1782 in a winter storm. She grounded on the rocks with such force that her fate was sealed. Many crew abandoned ship, getting into her two boats, a pinnace and a cutter. The pinnace reached Ash Point near Owls Head. There, some of the men chartered another boat and returned to Albany to take off the rest of the crew. They eventually returned to Castine.[34]

The cutter had difficulty from the start and soon got lost in poor visibility and freezing sleet. They began to row towards Castine, but conditions were horrible. Three aboard the cutter froze to death. The remaining men ended up on a beach on Matinicus Island. One source states islanders referred to the beach long afterwards as Dead Man’s Beach. Island residents took care of the survivors and buried the dead there. One story is that one sailor cried with shame and stated he had been part of a raiding party from Albany which had earlier landed on Matinicus and killed some of the islanders’ cattle.[35]

Although some sources suggest that the vessel had been stripped of cannons before serving as a transport, people reported seeing cannon that had gone down through the ship’s hull, among the rocks. One source reported that the keeper of Goose Rocks Lighthouse in Fox Islands Thoroughfare often made visits to the wreck, which was visible at low tide. Reportedly, he was able to see its guns during calm seas. A local Maine diver says that depth of what is left of the wreck at low or slack tide is about forty feet.[36]

A local Thomaston boy named Joshua Thorndike is said to have been part of a privateer crew out of Falmouth during the war. At some point, they were captured by Mowatt and Thorndike remained a prisoner aboard Albany for over nine months. When he learned of the ship’s wreck, he and some friends sailed out to the site and salvaged as much as they could. Thorndike called it a detested craft.[37] Capt. Henry Mowatt would likely have agreed, although he would have used the word “wretched.”

[1]The Despatches of Molyneux Shuldham, Vice Admiral of the Blue and Commander-in-Chief of His Britannic Majesty’s Ships in North America, January-July, 1776 (New York: Naval Historical Society, 1913), 6: 787; The New England Chronicle, September 12, 1776; Gardner Weld Allen, “Captain Hector McNeill of the Continental Navy,”Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 1922, 5. See also J. J. College, Ships of the Royal Navy (Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1987), 26.

[2]“Henry Mowatt” Mowatt Genealogy – Person Sheet, mowattfamilyhistory.ca/ps03/ps03_497.htm, accessed May 31, 2016; Harry Gratwick, Captain Henry Mowatt: The Maritime Marauder of Revolutionary Maine (Stroud, UK: The History Press, 2015), 95; and “George Jackson to Vice Admiral Shuldham, February 29, 1776”, Despatches of Molyneux Shuldham, 6: 105.

[3]“Lords Commissioners, Admiralty, to Vice Admiral Molyneux Shuldham, April 4, 1776”, William James Morgan, ed, Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1969), 4: 1015-16.

[4]George Athan Billias, ed., George Washington’s Opponents: British Generals and Admirals in the American Revolution (New York: William Morrow & Co., 1969), xvi.

[5]Gratwick, Maritime Marauder, 96; “Henry Mowatt” Mowatt Genealogy – Person Sheet; “Diary of Thomas Moffat, April 4, 23, 25, 28, June 1, 1776”, 8-D, Item 106 Peter Force Collection, Library of Congress; and Canceaux: Master’s Logbook (National Archives, Kew), Adm 52/1637, Adm 52/1638.

[6]“Albany” Wreckhunter.net,www.wreckhunter.net/DataPages/albany-dat.htm, accessed January 4, 2019; “Henry Mowatt” Mowatt Genealogy – Person Sheet; Harry Gratwick, Historic Shipwrecks of Penobscot Bay (ME: The History Press, 2014), 19; and Gratwick, Maritime Marauder, 100.

[7]American Vessels Captured by the British During the Revolution and War of 1812: The Records of the Vice-Admiralty Court at Halifax, Nova Scotia (Salem, Massachusetts: The Essex Institute, 1911), 63.

[8]“Transcripts of Entries of Letters in Vice-Admiralty Court, March 21, 1777” in Morgan, ed., Naval Documents, 8: 163; “Henry Mowatt” Mowatt Genealogy – Person Sheet; and Gratwick, Maritime Marauder, 99. See also “Master’s logs: Albany, 1776 June 2 – 1779 January 16,” ADM 52/1553, British National Archives

[9]Gratwick, Maritime Marauder, 100.

[10]“Henry Mowatt” Mowatt Genealogy – Person Sheet.

[11]Gratwick, Maritime Marauder, 104-105; and “Henry Mowatt” Mowatt Genealogy – Person Sheet.

[12]Henry I. Shaw Jr., “Penobscot Assault 1779” Military Affairs v17, No 2 (Summer 1953), 85; Jon Nielson, “Penobscot: From the Jaws of Victory” American Neptune (October 1977), 293; John Calef, The Siege of Penobscot (New York: William Abbatt, 1910), 2, 3; Russel Bourne, “The Penobscot Fiasco” American Heritage (1974), 29; A “Supplement” to the Nova Scotia Gazette and the Weekly Chronicle, July 6, 1779; Robert C. Brooks, “The Artificers and Inhabitants Who Built Fort George, Penobscot 1779-1780” Maine Genealogist (May 2004), 53; and Gratwick, Historic Shipwrecks, 22.

[13]Richard Hiscocks, “Commodore Collier’s North American Campaign – May to August 1779,” morethannelson.com/, accessed January 4, 2019.

[14]American Vessels Captured by the British During the Revolution and War of 1812: The Records of the Vice-Admiralty Court at Halifax, Nova Scotia (Salem, Massachusetts: The Essex Institute, 1911), 73-74; and “Masters’ logs: Albany, 1779 Mar 10 – 1779 Aug 21”, ADM 52/1552, British National Archives.

[15]“Entry for July 29, 1779, in Journal of the Attack of the Rebels”, Nova Scotia Gazette, September 14, 1779, Collections of the Maine Historical Society v7 (Bath: Maine Historical Society, 1876), 124; Gratwick, Historic Shipwrecks, 23-24; “Henry Mowatt” Mowatt Genealogy – Person Sheet; and Calef, Siege of Penobscot, 338.

[16]Joseph Williamson, “Thomas Goldthwaite” Bangor Historical Magazinev2 (1886), 87-89; Robert Goldthwaite Carter, Col. Thomas Goldthwaite – Was He a Tory? (Portland: Maine Historical Society 1896), 48; James H. Stark, The Loyalists of Massachusetts and the Other Side of the American Revolution (1907),354-358; Charles Bracelen Flood, Rise, and Fight Again: Perilous Times Along the Road to Independence (1976), 169-170, 198; E. Alfred Jones, The Loyalists of Massachusetts: Their Memorials, Petitions and Claims (1969), 146, 147-148; and Robert C. Brooks, “Refugees, Deserters, Prisoners on HMS Albany During the Siege at Penobscot July-August 1779” Maine Genealogist (November 2006), 173.

[17]Hiscocks, “Commodore Collier’s North American Campaign”.

[18]For more on the Penobscot Expedition see George E. Buker, The Penobscot Expedition: Commodore Saltonstall and the Massachusetts Conspiracy 1779 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2002).

[19]William M. Fowler, Jr., Rebels under Sail: The American Navy during the Revolution (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1976), 117; Jack Coggins, Ships and Seamen of the American Revolution (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1969), 167-68; James P. Baxter, “A Lost Manuscript containing Services of Henry Mowat, R.N.,” Collections and Proceedings of the Maine Historical Society 2d ser., v2 (1891), 364-65; Jones, The Loyalists, 146; David E. Maas, Divided Hearts: Massachusetts Loyalists 1765-1790 (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1980), 658; and Brooks, “Refugees, Deserters, Prisoners on HMS Albany”, 173.

[20]Gratwick, Maritime Marauder, 123; “Henry Mowatt” Mowatt Genealogy – Person Sheet; Baxter, “Services of Henry Mowat”, 345-75; and “Mowat’s Service Record” National Archives, Mowat Scrapbook, Charles E. Banks MSS, Maine Historical Society, Portland.

[21]John Pendleton Farrow, History of Islesborough, Maine (Bangor: T.W. Burr, 1893), 92.

[22]Gratwick, Historic Shipwrecks, 25; Farrow, History of Isleborough, 89; “Total Solar Eclipse of 27 Oct, 1780 AD,” moonblink.info/AEclipse/eclipse/1780_10_27; and “Total Solar Eclipse of October 1780” Bangor Historical Magazine v6 (Bangor: Joseph W. Porter, 1891), 63-65.

[23]Gratwick, Maritime Marauder, 127, 128-130; Edward Kalloch Gould, British and Tory Marauders on the Penobscot (1932), 5-32; “The British Occupation of Penobscot During the Revolution,” Collections and Proceedings of the Maine Historical Society, v1 (Portland: Brown, Thurston & Co., 1890), 392; and American Vessels Captured by the British,36; and “Masters’ logs: Albany, 1780 June 8 – 1782 June 8,” ADM 52/1552, British National Archives.

[24]James Phinney Baxter, ed., Documentary History of the State of Maine, Volume XVIII (Portland: Maine Historical Society, 1914), 96–98.

[25]American Vessels Captured by the British, 79.

[26]Baxter, ed., State of Maine, 301.

[27]American Vessels Captured by the British, 55, 57, 59-60; and “Masters’ logs: Albany, 1780 June 8 – 1782 June 8,” ADM 52/1552, British National Archives.

[28]American Vessels Captured by the British, 30, 38, 59, 74, 80, 86, 93; and “Masters’ logs: Albany, 1780 June 8 – 1782 June 8,” ADM 52/1552, British National Archives.

[29]“Robert Digby”Dictionary of National Biography v5 (London: 2004), 972; Gratwick, Historic Shipwrecks, 21, 27; Baxter, Mowat’s Service Record, 345-75; and Mowat Scrapbook.

[30]“Letter Henry Mowatt to Reverend Jacob Bailey August 11, 1782 – Halifax” in “Henry Mowatt,” Mowatt Genealogy – Person Sheet; Gratwick, Maritime Marauder, 130; “The First Father: Henry Mowatt” in “Henry Mowatt” Mowatt Genealogy – Person Sheet;Larry G. Bowman, Captive Americans (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press , 1976), 9; Allan Everett Marble, Surgeons, Smallpox and the Poor: A History of Medicine and Social Conditions in Nova Scotia 1749-1799 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993), 129-136; Dr. Allan Everett Marble, pers. comm.; Joseph Casino, Elizabethtown 1782: The Prisoner of War Negotiations and the Pawns of War (Trenton, NJ: New Jersey Historical Society, 1985), 6.

[31]“Mowat’s Complaint to Admiralty [n.d.],” Joseph Williamson MSS, Safe 1, Shelf 40, Maine Historical Society, Portland; Baxter, “Services of Henry Mowat,” 345-75; “Mowat’s Service Record” Gratwick, Maritime Marauder, 123; and “Henry Mowatt” Mowatt Genealogy – Person Sheet.

[32]Gratwick, Historic Shipwrecks, 21; and “Albany” Wreckhunter.com, www.wreckhunter.net/DataPages/albany-dat.htm, accessed January 4, 2019.

[33]NOAA Chart 13302; and “Albany” Wreckhunter.com. See also “Georgia” Wreckhunter.com.

[34]“Albany” Wreckhunter.com; and Gratwick, Historic Shipwrecks, 27.

[35]Gratwick, Historic Shipwrecks, 27.

[36]Ibid.; Edward Rowe Snow, Storms and Shipwrecks of New England (2005), 150, 164-165; and Rob Johnson, pers. comm. June 2015.

4 Comments

My compliments on an excellent article Charles. I have the ship muster books for the Albany and may perhaps answer a couple of your questions. The last cartel to Boston appears to have delivered 231 prisoners there on 26 November 1782. Mowat signs the final book covering the period November-December 1782, so it would appear he was still with the ship. According to the books, it looks lie Albany took at least 31 prizes during the war, and ferried many troops. Not a bad record at all.

Todd, thank you for your comment and information. Please contact me as I would like learn more about Albany’s final months from her September delivery at Boston to her December wreck.

Thanks for a detailed and well-documented article.

I’ve been doing research into the General Survey that Mowat worked on prior to the Revolution. The Surveyor General, Samuel Holland, did not have a very good opinion of Mr. Mowat. It seems Holland had to get orders issued to Mowat telling him to go along with his requests. Even at that, Mowat spent more time cruising for smugglers than following Holland’s orders–most notably taking soundings. That chore may well have been rather boring and seemed a useless activity to Mowat but the lack of soundings on the resulting maps and charts proved problematical to the Royal Navy in the years and decades following. Maybe Mowat’s attitude at this time carried over into his other doings in later years resulting in his being passed over.

Also, the “Canceaux” appears in Frederick Haldimand’s Papers a few times. It appears she spent a goodly portion of time during the Revolution on the St. Lawrence and “the lakes.” Some of her crew also found themselves seconded to ships on Lake Champlain. One of the midshipmen went by the name Fras. Mowat. He’s probably a relation but I haven’t looked into that question.

Just remembered something I forgot to mention: one must be cautious when using the term “sloop” in reference to ships in the period of the Revolution. Today the term refers to a single-masted boat with fore-and-aft sails but, for the British navy in the eighteenth-century, it can mean a “sloop of war.” The British used this term when talking about one of the lesser classes of ships in the rating system. A sloop of war might be what we think of as a sloop today but it could also be a two- or three-masted vessel rigged as a brig, for example, or even ship-rigged. The “Albany,” as pointed out in the first sentence of this article, fit into the “sloop of war” category.