By the evening of September 30, 1776, George Washington was, as he put it, “bereft of every peaceful moment.” During the previous month, his army had been badly mauled on Long Island and narrowly escaped destruction by executing a midnight evacuation to Manhattan. Forced to abandon New York City and take up defensive positions on Harlem Heights, Washington was exasperated on September 15 when his green troops were handily brushed aside by a British amphibious landing at Kip’s Bay.

Writing to his cousin Lund, a despondent Washington ruefully observed “that if I were to wish the bitterest curse to an enemy on this side of the grave, I should put him in my stead.” The general was determined to hold his ground, but lacked any confidence in his army’s mettle. “I am wearied to death all day with a variety of perplexing circumstances,” wrote Washington, “disturbed at the conduct of the militia, whose behavior and want of discipline has done great injury to the other troops, who never had officers, except in a few instances, worth the bread they eat.”[1]

Washington had good reason to question the reliability of his militia officers. Earlier that day, a general court martial had convened to investigate a bloody debacle occasioned by “Cowardice and Misbehaviour in the Attack made upon Montresor’s Island.”[2]

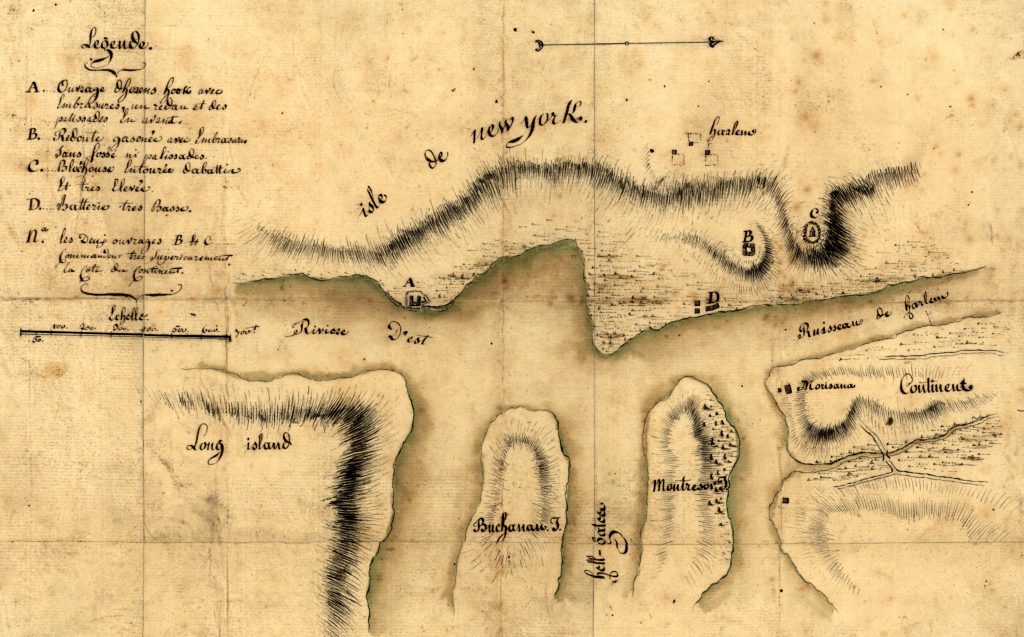

In the crucial battle for New York, Montresor’s Island had proved itself valuable real estate. The island, which lay in the East River about eight miles north of New York City, was ironically owned by the British military engineer John Montresor, whose property boasted a manor house and a complex of ancillary buildings including several barns and a farm office.[3] At the outset of the New York campaign, the island was largely undefended. The Americans had established a smallpox hospital on the island in the spring of 1776, which was guarded by about twenty men under the command of a subaltern.[4]

As British Gen. William Howe made plans for the invasion of Manhattan, he moved quickly to seize Montresor’s Island. At dawn on September 10, elite troops of the 1st and 2nd Battalions of Light Infantry landed on Montresor’s and Buchanan’s Islands.[5] Guarding the northern reaches of Manhattan Island, American division commander Maj. Gen. William Heath was alarmed by the flurry of activity across the Harlem River. On the evening of September 10, Heath reported to Washington that “the Enemy have been all this Day landing Troops on Montrosure’s Island where there appears to be a very large Number of them & Senteries posted all round the Island.”[6]

Heath’s alarm was justified. Situated so close to northern Manhattan, Montresor’s Island could afford Howe with the ideal jumping-off point for a major turning movement against the American left. “The possession of the Islands,” thought Capt. Frederick Mackenzie, “facilitates the landing of the Army on York [Manhattan] Island, and will protect the boats which may have occasion to pass” through the Hell Gate narrows.[7] Writing after the war, Gen. Henry Clinton, who could favor audacious flanking moves, claimed that he would have preferred bypassing Manhattan entirely. “We should . . . make every appearance of intending to force a landing on York Island,” Clinton suggested, “and when everything was prepared at Montresor’s Island (which I would have laid hold of for the purpose) throw the troops on shore from thence at Morrisania,” from where they could quickly block the rebels’ only escape route at Kingsbridge from the rear.[8]

Ultimately, although Howe would maintain a detachment of troops at Montresor’s property, he chose not to execute a major buildup on the island. By the middle of September, the only troops on the island seem to have been a 100-man detachment drawn primarily from the 71st Regiment of Foot, Fraser’s Highlanders.[9] The hold on Montresor’s Island, as well as control of the strategic Hell Gate narrows, was further strengthened on September 12, when His Majesty’s frigate Brune, which possessed an imposing complement of thirty-two guns, sailed up Long Island Sound and anchored near Montresor’s Island.[10]

Early on the morning of September 22, American commanders were presented with an unexpected opportunity to strike back. During the previous night, two sailors from the crew of the Brune jumped overboard and swam for the American lines, where they were eventually taken to General Heath for interrogation. According to the duo, Montresor’s Island was a pushover. The island, they claimed, was garrisoned by “but a few men.” Moreover, those troops were armed with nothing greater than small arms; a single piece of artillery had previously been assigned to the island, but had recently been removed to the Brune. John Montresor’s home was occupied by British officers, who were highly desirable targets for capture and interrogation, and a “considerable” amount of baggage and supplies were stored in the farm buildings.[11]

Heath called a council of his senior officers, who agreed that the enemy troops on Montresor’s Island could be “easily taken.” He then sought Washington’s endorsement for a plan to mount a raid on the island, dispatching Brig. Gen. George Clinton to headquarters for a face-to-face meeting with the commander-in-chief. Heath, however, was increasingly anxious to receive authorization for the raid immediately, and he dashed off another letter to Washington, citing fears that Clinton “may not return Untill late this afternoon, I am Desireous to Know your Excellency’s Opinion as Soon as you Please.” Heath was comfortable with the fresh intelligence regarding the strength of the British garrison, offering that “I think they may be taken without much difficulty.” Tellingly, Heath quickly scratched out the words “without much difficulty.”[12]

That afternoon, Heath was given free rein to run the operation. Writing on behalf of Washington, his military secretary Lt. Col. Robert Hanson Harrison informed Heath that the commander-in-chief “has no Objection to your making the Attempt you propose, If you are of opinion that the Intelligence given by the Two Lads is satisfactory & will Warrant It, and of which he says you are as good a Judge as he is.” Washington had a few stipulations, insisting that John Montresor’s home and outbuildings be spared unless it was absolutely necessary to burn them. Washington further highlighted the need for absolute secrecy in order to maintain the element of surprise. If the raid took place, it was imperative that American sentries posted along the Harlem River be informed in advance. “He requests,” wrote Harrison, “that you will acquaint him in time of the Resolution you come to in this Affair, that he may know how to conduct himself with respect to our Guards—If It is undertaken, they certainly must be apprized of It to prevent an Alarm.”[13]

Heath and his staff moved quickly to put the raid in motion, and by that evening a fairly detailed plan had been put together. Some 240 men would man about four flatboats for the assault on the island.[14] The plan as outlined by Heath called for the boats to descend the Harlem River on an ebb current and arrive at Montresor’s Island near dawn, just as a rising flood current covered the flats that surrounded the island, enabling the boats to reach the shore without running aground. A lead boat carrying field officers and a contingent of infantry would land first, immediately followed by two more infantry-laden boats which would land on each side of the first boat. According to Heath, a fourth flatboat carrying a three-pounder cannon would be at hand in case close artillery support was needed in order to cover a withdrawal.[15]

Although the information given by the two deserters was considered sound intelligence that demanded a quick response, the benefit of hindsight makes it abundantly clear that the raid on Montresor’s Island was rushed forward with undue haste. The operation would be carried out in less than twenty-four hours, and would be executed by green troops. The men had no time to train together for what amounted to an amphibious special operation, which, even in the best of circumstances, is considered one of the most notoriously difficult military endeavors to successfully execute.

The troops assigned for the raid were drawn from several units, including New York militia levies from Col. Isaac Nichol’s Regiment. At least a dozen men were drawn from the 7th Continental Regiment.[16] A smaller group of men were survivors of the 8th Connecticut, a Continental Line outfit that had nearly been captured en-masse at the Battle of Long Island.[17]

The operation would be led by Lt. Col. Michael Jackson; in an army of amateurs, Jackson, who had served under fire, was a sensible choice. After serving as a militia captain on the morning of the Lexington and Concord fight, he was wounded at Bunker Hill before earning his commission as the lieutenant colonel of the 16th Continental Regiment.[18]

Unfortunately, many of the officers who would lead the raid had no combat experience or hadn’t previously worked together on the battlefield. In addition to Colonel Jackson, the lead boat carrying the field officers would include Maj. Samuel Logan of the 5th New York and Maj. Moses Hatfield, a militia officer from Orange County, New York. [19] Hatfield secured an assignment to Col. Samuel Drake’s regiment of levies in June of 1776, but had been the subject of a court martial only two weeks before for “making a false report of the guards.”[20]

Capt. John Wisner, who would command troops aboard one of the two supporting infantry assault boats, had served as a company commander in Nichol’s Regiment of New York militia levies, but had seen little more that dull garrison duty at Fort Constitution.[21] In an era when familial connections could be a prime factor in securing a commission, Wisner possessed a respectable pedigree. His father, John Wisner, Sr., was a prosperous landowner and militia officer. His extended family owned and operated powder mills that supplied the Continental army; his uncle Henry was a delegate to the Continental Congress, and his cousin, Henry Wisner, Jr., was a well-respected militia officer. Despite such sterling connections, Wisner apparently possessed a reputation for unpredictable behavior. John McKesson, secretary of New York’s provincial congress, hoped that Wisner would do his duty but considered him “weak and flighty.”[22]

Another officer who was determined to accompany the raid was Heath’s aide Maj. Thomas Henley. Heath initially turned him down, explaining that the raid was simply no place for an unattached staff officer. Henley “grew impatient,” returned the Heath’s quarters, and again requested permission to go along, asking Heath to “let me have the pleasure of introducing the prisoners to you tomorrow.” Against his better judgment, as well as the advice of other officers who were present, Heath relented.[23]

At about 11 P.M. on the evening of the September 22, American sergeants from Heath’s Division began rousting bleary-eyed men from their tents. In the interest of tight security, the enlisted men didn’t appear to have been briefed on the mission and “were soon after embarked in the boats, without knowing where they were going, or for what purpose.”[24] Messengers had been dispatched to the American sentinels along the Harlem River with orders to keep quiet. With everything in place for the raid, Heath and his staff went to the shoreline for a better view of the operation.

Out on the river, the raid started out badly. The troops hadn’t been in the water long when George Marsden, the adjutant of the 7th Continental Regiment, noticed a man squatting in the bottom of the boat. Not a little annoyed, Marsden gave him “a kick or two.” Marsden was startled when he noticed a captain’s badge in the man’s hat, and asked him “what officer he was.” The man replied he was a captain. It was John Wisner.[25]

Wisner explained that some of his men were serving as sentries along the Morisania shoreline, and that they had observed “five Times the Number of the Enemy on the Island that we thought for, & that we were led into a plaguy Scrape.” He further warned that the Brune frigate was anchored in the vicinity of the island and could “rake us with Grape Shot.” When they caught sight of an unidentified vessel, Wisner jumped to the worst conclusion and blurted out “there’s the Man of War.” The enlisted men, hard at the oars, were understandably alarmed when they overheard the conversation.[26]

While the argument continued on Wisner’s boat, disaster struck. Although American sentinels along the Manhattan shore had been informed of the operation, one guard had inexplicably been missed. Oblivious that he was threatening the lives of his fellow soldiers, the sentinel dutifully shouted a challenge to the passing boats and ordered them to come to shore. Listening from a vantage point on the bank of the Harlem River, Heath heard the entire exchange. One of the officers in the boats answered “Lo! we are friends.” The sentinel would have none of it, and repeated his challenge. “We tell you we are friends,” came a response, “hold your tongue.”[27]

One of the boats abruptly halted in front of Heath, and an officer waded through the shallows toward the general. It was Henley. Clearly worried that enemy pickets would hear the commotion, Henley asked Heath “Sir, will it do?” Apparently of the opinion that it was too late to call off the operation, Heath responded “I see nothing to the contrary.” As he turned back to his boat, Henley responded “Then it shall do.”[28]

As the flotilla proceeded, the sentinel was unrelenting. “If you don’t come to the shore,” he shouted, “I tell you I’ll fire.” Left with few choices, one of the officers in the boats ordered his crew to “Pull away.” At that, the sentinel touched off a single shot from his firelock.[29] The ball did no immediate damage, but as the musket’s report reverberated across the surface of the Harlem River, the element of surprise was irretrievably lost. The British garrison on Montresor’s Island had heard the shot.

When the shot was fired, Wisner once again ducked into the bottom of his boat. Capt. James Eldridge then told him to get up, to which Wisner replied that he “did not chuse to be in the Way of those plaguy Balls,” and repeated the warning that the island was heavily defended, and that the British frigate would cut them to pieces.

Oddly enough, Wisner’s fears weren’t without foundation. The intelligence that the two deserters had brought in was only partly accurate. According to Frederick Mackenzie, the island was still guarded by a captain and one hundred men, who, thanks to the American sentinel’s musket being fired, had been alerted to a possible American attack. “Having discovered them approaching,” reported Mackenzie, British officers hastily prepared to repel an American landing. The plan was to allow the Americans to make landfall, “and then, before they could put themselves in order, to rush suddenly on them with Bayonets fixed.”[30]

As the boats made the final approach to Montresor’s Island, bedlam erupted. Contrary to orders, British troops prematurely opened fire on the boats. Wisner crouched in the bottom of the boat and Eldridge claimed that “I gave him several Kicks with my Foot which he did not attend to.” When the firing increased, Jotham Baker heard Wisner shout “for God’s Sake Retreat or we shall all be cut off.” The fear was contagious. Both Marsden and Eldridge claimed that they tried to restore order, but that “the men laid down in the Boat and were not to be governed.”[31]

“Chaos ensued,” claimed Eldridge. The men became so panic stricken and confused that two of the supporting boats ran afoul of each other. Corporal John Kilburn, sitting two seats away from Wisner, claimed that Wisner’s behavior had completely demoralized the men, and that “the Confusion was great.” An officer at the front of the boat, who was thought to be Eldridge, tried to get the men moving toward the island and shouted “Clap to your oars Boys we shall be safer on shore than here.”[32]

At Montresor’s Island, the situation was even worse. The lead boat carrying the field officers had landed as planned, but came under immediate attack. Troops from the 71st Regiment rushed toward the boat and opened fire, throwing Colonel Jackson and his party in confusion.[33] According to Col. John Glover, Jackson “called to the other boats to push and land, but the scoundrels, coward-like, retreated.”[34] As he attempted to rally his men, Jackson collapsed when a ball shattered his leg. Hard pressed by the Highlanders and lacking any support from the other boats, the Americans on the beach scrambled back for the safety of their own boat. Jackson was carried to the craft and placed inside; as Thomas Henley was climbing aboard, he was shot through the chest and collapsed over the gunwhales.

In the mad dash for safety, British troops snapped up prisoners, which included Major Hatfield, and maintained a fire at the boats, “which was continued on them,” reported Mackenzie, “as long as they were in sight. They rowed off in great confusion.”[35] The other boats, which never made it to shore, provided little more to the operation than a chaotic display of inaction. The officers had been unable—or unwilling—to regain control of their men and press the attack. At least one man in Wisner’s boat was shot dead. Marsden explained that “so much Confusion ensued that we were obliged to land at Morisania.”[36]

Aboard Jackson’s lead boat, there were far fewer men available to row due to the number of casualties left on the island. Jackson was in agony, Henley’s corpse lay in the bottom of the boat, and one man, mortally wounded, reportedly succeeding in rowing his comrades to safety before he “died at the oar.”[37]

The raid on Montresor’s Island had been a costly and embarrassing disaster for the Continental army. Precise figures of American losses remain elusive. Heath would later record fourteen men killed, wounded, and missing.[38] Mackenzie recorded that “one of the Majors and 13 men were taken prisoners; and some were killed and wounded.” During the rather-one sided exchange of gunfire, Mackenzie reported that two Britons from the 71st were killed.[39]

The loss of Henley, who was a popular officer, was a bitter pill for the Continental army. “We last Night lost a most intrepid Officer,” Lt. Col. William Tudor informed John Adams, who “fell a Sacrifice to the Cowardice of some Poltroons. This young Officer is universally lamented he bid fair to have been a great military Character.”[40] News of the disaster spread quickly; on September 25, a letter from Brig. Gen. John Morin Scott announcing the raid was read before the New York provincial congress.[41] On the afternoon of September 24, Henley, eulogized in general orders as a “brave and gallant soldier,” was laid to rest.[42]

Massachusetts congressional delegate John Adams gave voice to a widespread desire for retribution. Writing to Col. Daniel Hitchcock, Adams explained that he was “vexed and mortified” by the shameful outcome of the raid on Montresor’s Island. “Pray inform me what Officers and Men were sent upon that Attempt,” asked Adams. “It is said, there was shameful Cowardice. If any Officer was guilty of it, I sincerely hope he will be punished with death. This most infamous and detestable Crime, must never be forgiven in an Officer.”[43]

For his part, Washington was of the same opinion, and with Henley buried, the general quickly got to work insuring that the officers responsible for the debacle faced military justice. Just three days following the defeat, Washington’s aide Capt. Tench Tilghman reported that an initial inquiry was underway. “A very strict scrutiny is making into the conduct of the officers who thus shamefully deserted,” wrote Tilghman, “and it is expected they will meet the fate this cowardice deserves.”[44] On September 29, a general court martial was ordered to convene for “the Trial of Capt: Weisner & Capt. Scott for Cowardice and Misbehaviour in the Attack made upon Montresor’s Island.”[45] Although the unidentified “Captain Scott,”who was likely in one of the other flatboats, was spared an immediate trial, Wisner’s life was at stake.[46]

The court, headed by Brig. Gen. Rezin Beall, convened on September 30, and heard damning testimony from six men—which included officers, non-coms, and enlisted men—who had been aboard Wisner’s boat. But the defense called an additional six enlisted men who cast a measure of doubt on the prosecution’s case. One of Washington’s aides, Lt. Col. Samuel Blachley Webb, clearly expressed the expectations at headquarters when he informed his brother that the verdict of Wisner’s trial was expected to be announced soon. “If our people are in a hanging mood,” Webb wrote, “I think he stands a chance to swing.”[47] When Beall announced the verdict, Wisner was found guilty of misconduct and cowardly behavior but, contrary to expectations, was spared the firing squad and sentenced to be cashiered.

Wisner’s relatives scrambled to contain the damage done to their family’s reputation. On October 4, his cousin Henry forwarded a note to New York Brig. Gen. George Clinton in which he asked for further details on the failed raid. “The accounts I have are so Broken that I don’t Know what to Believe or what not,” but, he confessed, “I dare say the accounts are Bad enough.” Motivated by his regard for Wisner’s heartbroken father, he then asked Clinton’s help in giving his “unhappy Cousin” a second chance. Perhaps, he suggested, Wisner could be afforded “an opertunity in some measure to Recover his Character By fighting without the lines . . . I think he may safely doe that now, as the venture will not Be very great, unless he sets a higher value on himself now then he aught to doe.”[48]

General Washington was far less disposed to sympathy, and when informed of the outcome of the trial, was displeased with the sentence. Outraged at Wisner’s abysmal performance under fire, which had clearly contributed to disaster and endangered the lives of the men, the general immediately forwarded a forceful recommendation to the presiding officers of the court-martial that they reconsider the sentence. Washington, who demanded that his junior officers set a personal example of bravery on the battlefield, was hopeful to establish a stern precedent for cowardice in the face of the enemy. He wanted Wisner shot.

In an October 5 remonstrance to General Beall, Washington’s adjutant general Col. Joseph Reed expressed the commander-in-chief’s dismay at the lenient sentence. Washington, Reed Wrote, “has directed me . . . to remark that the discretionary power of the Court seems to have been exercised rather from some motive of compassion than any circumstance appearing on the face of the proceedings.” Considering the fact that Wisner had actually been found guilty of cowardice, Washington demanded an explanation for the light sentence. Alarmed that such a sentence would erode morale and discipline, Washington was concerned that enlisted men would view the entire affair as a blatant act of favoritism toward a commissioned officer. “To convict an officer of the crime of cowardice,” concluded Reed, “and in a case where the enterprise failed on that account, where several brave men fell because they were unsupported, and to impose a less punishment than death, he is very apprehensive will discourage both officers and men.”[49]

The following day, Beall replied for the members of the court, who rather bluntly let Washington know that, having actually heard the verbal testimony of the court-martial, they considered themselves “the best, the sole judges” of the case. The officers didn’t believe that Wisner’s behavior was the only cause of the raid’s failure, and were unsettled by the contradictory nature of some of the testimony. Considering the fact that Wisner’s life had been at stake, Beall was uncomfortable with some of the testimony from other officers, as “Throwing the fault on some one or more persons might be essential to their own justification and preservation.”[50] Stymied in his efforts for a harsher sentence, Washington finally approved the sentence of the court on October 31.

The particulars of John Wisner’s service at Montresor’s Island apparently remained a dark secret within the family. His children were aware that he had served as a militia captain in the vicinity of Fort Constitution. But according to his daughter Hannah Vanhouten, the family was under the impression “that her father went into the war at the commencement of said war and did more or less service throughout the war.” Another daughter, Anna Post, was led to believe that her father had served at least three years and “came near being killed in a battle in said war.”[51] Somewhat understandably, the family seemed unaware that George Washington had wanted the family patriarch executed.

For the family of Michael Jackson, there were no illusions of grandiose Revolutionary exploits. During surgery on his shattered leg, over thirty bone fragments were removed from the wound, and physicians attested to the fact that he could “never expect to have the free use” of the limb again.[52] Appointed colonel of the 8th Massachusetts in January of 1777, he was nonetheless regarded as “very lame & unfit for Duty.”[53]Eventually breveted a brigadier general, Jackson remained incapable of an active field command. Due to his ghastly combat wound, he struggled with chronic pain and a severe limp for the remainder of his life.

When Jackson died in 1801 at the age of sixty-six, the inscription carved on his tombstone was a moving reminder of a life permanently altered by the brief firefight at Montresor’s Island:

General Michael Jackson

Filial Piety, conjugal

Affection, Parental tenderness,

The virtues which adorn

The Patriot, the Citizen,

And the Soldier,

Shone conspicuously in him.

Long oppressed with a wound

Sustained in his countrys cause

AD 1776

He died with the firmness

of a true Christian.

10th April AD 1801

[1]George Washington to Lund Washington, September 30, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-06-02-0341.

[2]General Orders, September 29, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-06-02-0328.

[3]G.D. Scull, ed., The Montresor Journals(New York: New York Historical Society, 1882), 126. American troops were widely credited with burning Montresor’s property in January 1777. General Heath, however, would later lay the blame on skittish British sentries. Heath, Memoirs, 104. The island is now known as Randall’s Island.

[4]General Orders, April 19, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-04-02-0068.

[5]Frederick Mackenzie, The Diary of Frederick Mackenzie (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1930), 43.

[6]William Heath to George Washington, September 10, 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-06-02-0219.

[8]William B. Willcox, ed., The American Rebellion: Sir Henry Clinton’s Narrative of His Campaigns, 1775-1782 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954), 44-45.

[10]William Bell Clark, Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Washington: Department of the Navy, 1969), 4:982. Mackenzie, Diary, 44.

[11]William Heath, Memoirs of Major-General William Heath By Himself (New York: William Abbatt, 1901), 55-56.

[12]Heath to George Washington, September 22, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-06-02-0289.

[14]Sources vary on the number of men and boats, from 140-300 men and four to six boats. Heath would record 240 men and four boats. Heath, 58. John Glover recorded 240 men and six boats. John Glover to Tabitha Glover, October 7, 1776, in Henry Phelps Johnston, The Campaign of 1776 Around New York and Brooklyn (Brooklyn: Long Island Historical Society, 1878), part II, 99.

[16]George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Continental Army Court Martial, Proceedings at Harlem Heights, New York. 1776. Manuscript/Mixed Material. www.loc.gov/item/mgw445833/. George Marsden testified that he initially boarded his boat with a “Sergeant and twelve Men.”

[17]Peter Force, American Archives(Washington: 1853), 5th series, 3:718. A regimental return lists two men from the 8th Connecticut, David Spencer and Matthias Button, missing in action at Montresor’s Island, and one man, Ralph Lines, initially missing but later located in an army hospital.

[18]Francis Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army (Washington: W.H. Lowdermilk, 1893), 239-240.

[20]General Orders, September 12, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-06-02-0229.

[21]Public Papers of George Clinton (New York: Wynkoop Hallenbecck Crawford Co., 1900), 1: 137.

[25]George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Continental Army Court Martial, Proceedings at Harlem Heights, New York. 1776. Manuscript/Mixed Material. www.loc.gov/item/mgw445833/.

[31]George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Continental Army Court Martial, Proceedings at Harlem Heights, New York. 1776. Manuscript/Mixed Material. www.loc.gov/item/mgw445833/.

[34]Johnston, The Campaign of 1776, part 2, 99.

[36]George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Continental Army Court Martial, Proceedings at Harlem Heights, New York. 1776. Manuscript/Mixed Material. www.loc.gov/item/mgw445833/.

[37]Johnston, The Campaign of 1776, part 2, 99.

[39]Mackenzie, Diary, 63. Archibald Roberston reported the capture of one American major and thirteen men, and eight British casualties. Archibald Robertson, Archibald Robertson: His Diaries and Sketches in America, 1762-1780 (New York: New York Public Library, 1930), 100.

[40]William Tudor to John Adams, September 23, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-05-02-0019.

[41]Journals of the Provincial Congress, Provincial Convention, Committee of Safety and Council of Safety of theState of New York (Albany: Thurlow Weed, 1842), 642.

[42]General Orders, September 24, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-06-02-0298.

[43]John Adams autobiography, part 1, “John Adams,” through 1776, sheet 51 of 53 [electronic edition]. Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive. Massachusetts Historical Society. www.masshist.org/digitaladams/.

[44]Peter Force, American Archives (Washington: 1851), 5th Series, 2: 523.

[45]General Orders, September 29, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-06-02-0328.

[46]“Captain Scott” cannot be definitively identified. For a brief discussion on the confusion regarding Scott’s identity, see Enis Duling, “Arnold, Hazen, and the Mysterious Major Scott”, Journal of the American Revolution, February 23, 2016, especially note 37.

[47]Washington Chauncey Ford, ed., Correspondence and Journals of Samuel Blachley Webb (New York: 1893), 1: 168.

[48]Public Papers of George Clinton, 1: 368.

[49]Peter Force, American Archives (Washington: 1851), 5th series, 2: 895.

[51]G. Franklin Wisner, The Wisners in America and Their Kindred (Baltimore: 1909), 117, 114-115.

[52]Note 1, George Washington to Thomas Mifflin, January 19, 1784, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-01-02-0040.

[53]“John Brooks to George Washington, February 21, 1777, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-08-02-0429.

4 Comments

Great article, Joshua Shepherd. I mention the raid on Montresor’s Island in the article, “1776–The Horror Show” (Journal of the American Revolution, January 29, 2019). The soldiers captured at Montresor’s were among 4,000+ POWs crowded into various facilities that winter.

I’m grateful to learn more about the officer and 13 soldiers who became prisoners after this raid.

Confusion Alert! An interesting investigation and great article, thanks. . . . but alas, the author has, not unsurprisingly, confused the Wisners. They confuse just about everyone. The John Wisner who was on this mission was John Wisner, Sr. (c.1718-1778). He was the BROTHER of Henry Wisner of the Continental Congress (there are THREE Henry Wisners active in the Revolution, furthering the confusion). Capt. John, Sr. was an experienced militia commander and had seen deadly combat during the French and Indian War. His company was Continental line (more or less) at this time. He was in his early to mid 50s, and had ample opportunity to know that Washington and some of his officers might not always make great decisions. He had had further cause to be dubious, as his company had just endured being told to “march down the ice” of the Hudson to Ft. Constitution since the roads were bad. Two of his men talk about the harrowing shifting of the ice as they marched in their pension applications. “Friends of Hathorn House” have researched this man extensively. There was no room for movement or defense in the troop flatboats. Wisner could let his men be slaughtered, or withdraw. His Court Martial officers confirmed their sparing of his life under mitigating circumstances when Washington had his aide question their decision—”attempted interference with the judiciary”—they pushed back. John, Sr. died two years later, having been cashiered for this action. His son, Capt. John Wisner, Jr., continued in service, with a good record, throughout the war.

Thank you for your comment, Ms. Gardner. You’re certainly correct, there’s a good bit of confusion on the Wisners, so many Johns and Henrys! Some of the primary accounts are helpful. In his letter to George Clinton after the raid, Henry Wisner (Jr.) refers to the John of Montresor’s Island as “my unhappy cousin, John Wisner”, and then mentions that the “perticuler Regard I have for his father gives me great pain.” (Public Papers of George Clinton, 1: 368.) John Sr.’s father Hendrick died a decade before the war, so it seems unlikely he’s the “father” being mentioned. John Sr. would have been in his late 50’s at the time of the raid.

In an 1825 pension application, John Jr.’s daughter Anna Post recalled living with her paternal grandfather, John Sr., during the campaign of 1776 while John, Jr., was away on active service. (The Wisners in America and Their Kindred, 114-115)

Thanks again for the interest!

Will be happy to share the sources showing that this man was John Wisner, Sr. if you wish to contact us. Identifying him correctly is of local interest only…. We note that “cousin” is a term indicating nonspecific relationship at this time; Henry Wisner Sr. of Cont. Congress wrote the letter in GC papers Vol 1 item 190 as shown by internal evidence of writing style; neither of the Johns of that time was his “cousin” as we calculate relationships today. Capt. John Wisner, Jr. is the man who persists in the military records after this time period, which never would have been allowed after a court martial. John Sr. died in 1778 and is noted as having a military career “ending badly” in 1878 Memorial of Henry Wisner by Franklin Burdge, the only mention in print.