“Be a King George.” Four simple, but oft repeated words drilled into the Prince of Wales from childhood by his mother, Augusta of Saxe-Gotha. And through a faithful adherence to her command George lost an American Empire.[1]

In 1751 Princess Augusta was widowed unexpectedly on the sudden death of George’s father Frederick. Though a tragedy, it did at least provide her with the opportunity to remove herself from the rancorous bear pit of Hanoverian court politics.From then on she chose to live in the relative seclusion of Leicester House and devote herself entirely to the care of her children. Here the dowager princess guarded her brood of nine so jealously that it was noted they seldom met anyone from outside.[2]

In this secure but uncritical environment Augusta inevitably emerged as the dominant force in the Prince’s life. “The mother always prevailed,” his tutor Lord Waldegrave later noted warily.[3] She became his champion and confidante, a devoted if domineering matriarch whose advice George never questioned.

As the young Prince grew into maturity Augusta’s dominance inevitably evolved a political dynamic. “I am going to carry a copy of this unworthy letter to my mother,”[4] the young heir threatened when his grandfather George II refused his request to be promoted to commander-in-chief.

Even at twenty-one the Prince steadfastly refused to move out of the family home, despite his grandfather offering him his own sumptuous wing in St. James palace as befitted an heir apparent. George wrote to the King, “I hope that I shall not be thought wanting in the duty I owe Your Majesty, if I humbly . . . remain with the Princess my Mother; this point is of too great consequence to my happiness for me not to wish . . . indulgence in it.”[5]

It was unavoidable in the artificiality of this closed social environment that George’s openness to experience never fully developed. As a child he reacted badly to criticism and became morose and withdrawn if challenged. The consequences of this lifelong character trait were to be profound. Throughout his reign he repeatedly pursued his own narrow viewpoint long past the point where he was clearly in the wrong. It was a personality defect only exacerbated by his habit of seeking advice from a handful of trusted confidantes, most of whom lacked the energy or guile to contradict their king.

Both characteristics impaired any creative or inquisitive solutions to affairs of state that a more open and less pugnacious monarch may have pursued. This was especially pronounced during the American war where the King’s obdurate nature and over-reliance on a few key ministers emerged as principal reasons for Britain’s defeat.

George’s character flaws are vividly illustrated in a series of remarkable letters, many of which have only recently been opened to public scrutiny. The survival of this apparently long-lost collection was extremely fortunate as they were found labeled, “To be destroyed unread,” in the basement of Apsley House nearly a century after they had been placed there by the Duke of Wellington, the principal executor of George IV.[6]

It is a comprehensive and surprisingly intimate collection that reveals a touching if naive motivation behind the monarch’s attempts to subdue the Revolution. Like a wayward child, America must “remain attached to the Mother Country.” On this point George is both persistent and uncompromising. It is a phrase he repeats on numerous occasions throughout the papers and it does not take a Freudian psychotherapist to see buried in this idiom the embers of his own authoritarian upbringing.

To George, the domineering mother and her infallible lover Lord Bute were the personification of all that was laudable in the British character. As a Prince they taught him that duty, honor and loyalty were, above all else, the principles on which manhood and statehood were founded. And George would never falter from this guidance. In his turn as King, whether with his own recalcitrant brood at Windsor or his non-compliant subjects across the Atlantic, George would insist on that same loyalty and devotion. Predictably, this authoritarian attitude accomplished identical, if to the King incomprehensible, results. Both his sons and his subjects rebelled from royal authority.[7]

The earliest letters in the collection reveal an earnest, if insecure, young man struggling with the monumental pressures of his position.His zealous desire not to disappoint is at times almost painful to read. He writes to Lord Bute plaintively, “I see plainly that I have been my [own] greatest enemy: for had I always acted according to your advice I should now have been the direct opposite from what I am.”[8]

A pronounced sense of personal loyalty is displayed throughout his writings, but more darkly so too an almost pathological fear of abandonment.In many of the letters it is only too easy to transpose his childhood mentor Lord Bute for America. “I do hope you will from this instant banish all thoughts of leaving me and will resolve for the good of your country to remain with me,”[9] he wrote him, whilst in a later prophetic note he added, “If you should now resolve to set me adrift, I could not obraid you, but on the contrary look on it as natural consequence of my faults, and not want of friendship in you.”[10]

Writing to Bute as a sixteen year old boy he castigated the ministers of his grandfather George II. “They have treated my Mother in a cruel manner which I shall neither forget nor forgive until the day of my death. My Friend [Bute] is also attacked because he wants to see me come to the throne with honour. I look upon myself as engaged . . . to defend my friends as long as I draw breath.”[11] He continued with perhaps the most telling phrase seen in any of his private or public papers. In an echo of his mother’s epithet “be a king George” he solemnly declared, “I will take upon me the man in everything . . . I have chosen the vigorous part . . . and will never grow weary of this.”[12]

It is clear that even as an uncrowned Prince George intended a reign unlike any of his Hanoverian predecessors. He would never rule as a mere cypher. George would prove to his people that he was not a German elector reluctantly transported onto a foreign throne. He was emphatically King of Great Britain. “It has been a certain position with me that firmness is the characteristic of an Englishman,”[13] he later confessed.

Unfortunately the very same “firm” and “vigorous” characteristics he so lauded as attributes of his people in Britain produced fatal political consequences when dealing with “Englishmen” with similar characteristics across the Atlantic. George was almost entirely responsible for diplomatic failures early in the war, when his aggression and intransigence destroyed Britain’s only plausible opportunity to work through a peaceful solution to the Constitutional crisis.

“If we take the resolute part they will prove very meek.”[14] George’s letter to Lord North on the eve of the war was characteristic of his approach to the rebellion throughout the remainder of the conflict. Only by action and firmness could Britain overcome a Revolution he willfully downplayed as mere “disturbances.”

He alone perversely sponsored the notion that it was his ministers leniency, not their misjudgment, that had given rise to the initial revolt. He sarcastically noted, “if unaccounted with the conduct of the mother country and its colonies [one] must suppose the Americans poor mild persons who . . . had no choice but slavery or the sword; whilst the truth is too great lenity in this country increased their pride and encouraged them to rebel.”[15]

The letters reveal consistent demands for coercive action on the part of his ministers and generals that sit uncomfortably alongside modern histories that sympathetically portray George as acting mostly upon bad advice. They reveal that, on the contrary, he received competent and honest appraisals of the situation in America throughout the war. He simply chose to ignore intelligence that conflicted with his own views on how the rebellion should be quashed.

On the first reports from Concord and Lexington in 1775 the MP Thomas Pownall declared in Parliament that he believed the beginning of hostilities to be “bad news.” To everyone else in the House this seemed self-evident. George however was indignant. He wrote, “As to Mr Pownall’s expression of ‘bad news’ it shows he is more fit for expediting the directions of others than he would have been for a military department . . . where firmness is required.”[16] In fact Pownall had been the colonial governor of both the Province of Massachusetts Bay and New Jersey, had travelled widely in the North America and knew better than most the attitudes of colonial Americans and the perils British authority was under. But “bad news” was not what George wanted to hear.

Defeats of arms he brushed aside in a similar cavalier fashion. After the disastrous winter defeat at Trenton, George wrote nonchalantly, “the accounts from America are most comfortable,” before going on to contradict himself by blaming the humiliation on the Hessian officers’ “want of spirit.”[17] He ended optimistically, “I have seen a letter from Lord Cornwallis that the rebels will soon have sufficient reason to fall into [their] former dejection.”[18] It was a delusion he was to never cast off.

As the war progressed George continued to see only what he wanted to see. General Howe’s dilatory actions around New York were greatly criticized by his contemporaries as having allowed Washington and his army the chance to slip away unmolested. It was arguably the greatest military blunder of the war, as a more aggressive commander could have captured the Continental army wholesale. The King, however, resolutely refused to portray it as a mistake. “I differ widely with [lord North] as to bad news being likely from New York . . . I reason just the contrary, that Howe by delay has so much better concentrated his manoeuvres . . . and will strike the more decisive blow.”[19]

But a decisive blow never came, and the arrival of France and Spain into the conflict and a military stalemate on the American continent emboldened Whig critics of the war in Britain. Relentless parliamentary motions attacking the continuation and direction of the conflict began to grind down Prime Minister Lord North. But not so George. He wrote to North without a trace of irony, “the present accounts from America seems to put a final stop to all negotiations. Further concession is a joke.”[20] For In fact he had rejected all concessions and had done his best to hamstring politicians with more conciliatory views. He concluded with a magnificently bellicose if unrealistic clarion call: “We must content ourselves with distressing the Rebels . . . till the end of the [French] war . . . which will oblige the Rebels to submit.”[21]

He reacted with predictable horror when in 1779 Sir William Meredith tabled a parliamentary motion for peace with America, writing, “nothing can incline me to enter into what I look upon as the destruction of the Empire.”[22] He regarded the City of London as particularly treacherous, it being short-sightedly obsessed with issues of finance and trade rather than honor and duty.[23] He commented condescendingly if presciently, “if persons sit down and weigh the expense they will find . . . [the war] has impoverished the state . . . and raised the name only of the [Americans] . . . but this is only weighing events in the scale of a tradesman behind his counter. Divine Providence [has] placed me to weigh whether expense, though very great, is not sometimes necessary to prevent what may be more ruinous to a country than loss of money.”[24]

But the King’s subjects in Britain continued in increasing numbers to oppose the American war. Throughout the remainder of the struggle George’s “Divine Providence” seemed to be sleeping.

In April 1780 the MP John Dunning tabled a famous motion in Parliament that “the influence of the Crown has increased, is increasing and ought to be diminished.”[25] Shockingly the motion was passed by 233 to 215. Just a century on from the “Glorious Revolution” that had replaced the Stuart monarchs, George now received a terse warning from a sizable section of his subjects. Where the Stuarts had gone the Hanoverians could easily follow.

George’s response was predictable. He called for national unity in a nation already fatally divided, and resolutely refused to even consider ending the conflict unless independence was removed from the negotiations. “Every means are to [be] employed to keep the empire entire, to prosecute the present just and unprovoked war in all its branches with the utmost vigour and . . . his majesty’s past measures . . . treated with proper respect.”[26]

Whatever the year, whatever the military or political state of the rebellion, George remained intransigent. He was emphatic, resolute but fatally deluded. “The next campaign will bring the Americans in a temper to accept such terms as may enable the mother country to keep them in order . . . the regaining of their affection is an idle idea. It must be the convincing them that it is in their interests to submit.”[27] For George it was always the next campaign. Always one small step away from reducing the Rebels to submission and convincing them they would be better off remaining with the mother country.

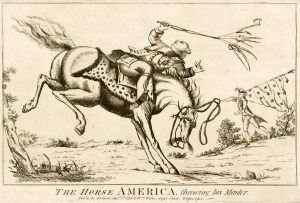

But it was a fantasy. The Revolution became a disastrous world war. The Dutch joined the American coalition, the French invaded the British Island of Jersey and Minorca was lost to the Spanish. The defeat at Yorktown finally dealt the coup de grace to the ambitions of all who argued for a continuation of the conflict. All, that is, except the king himself. “I have no doubt that when men are a little recovered of the shock felt by the bad news . . . that they will find the necessity of carrying on the war.”[28] But Lord North was more realistic. “My God it is all over,” he repeated over and over on the intelligence from Yorktown.

Still George remained almost obsessive in his attempts to chivvy up support for the war long after even his most loyal ministers had given up the ghost. As late as spring 1782, he clung to the bizarre notion that parts of America could be saved. Attempting to form an administration to replace Lord North he insisted he would take MPs of any party or faction with just a single proviso, that they agree on the condition of “keeping what is in our possession in North America, and attempting by a negotiation with any separate province or even district to detach them from France, even upon any plan of their own, provided they remain separate states.”[29] But by 1782 it was a delusion both politically and militarily. The United States existed as a single political entity and Britain would have to negotiate with it, with or without the Kings acquiescence.“Knavery seems to be so much the striking feature of its inhabitants,” the King wrote to Lord Shelbourne, “that it may not in the end be an evil that they will become aliens to this kingdom.”[30]

“When I am dead and chested you will find Calais engraved on my heart.”[31] Though George lacked the poetic temperament of his royal predecessor Mary Tudor there is little doubt he experienced similar remorse over the loss of America as she did Britain’s remaining French colony. For the rest of his reign the humiliation appears to have tormented his mind.

In 1782 George descended into a fit of melancholia over the weight of the defeat. Humiliated, and in his own mind abandoned by his indecisive ministers, he drafted an abdication speech. It was a remarkable document evoking the same intransigent attitudes at the end of the conflict as at the beginning of it. Writing in the third person, he exclaimed, “his majesty is convinced the sudden change of Legislature has totally incapacitated him from conducting the war with effect or from obtaining any peace but on conditions which would prove destructive to . . . the British nation. His majesty therefore with much sorrow finds he can be of no further utility to his native country which drives him to the painful step of quitting it forever.”[32]

How serious George was about abdicating in favor of his son, we can never know, but the relinquishing of a crown voluntarily was a luxury no British monarch had undertaken for a thousand years. Ultimately George’s attachment to his Nation and his sense of honor and duty prevailed over his personal despondency, and the constitutional crisis never materialized.

Obdurate and deluded as he was, he yet possessed a remarkably prescient understanding what the ultimate outcome of the peace treaty would be for Britain. He predicted that “the present contest with America I cannot help but seeing as the most serious in which any country was engaged. It contains such a train of consequences that they must be examined to feel its real weight.”[33] He correctly surmised that if America gained its independence she would become a serious rival to the British Empire in the coming decades. He also correctly anticipated that Britain’s other colonies and ultimately Ireland would follow America’s course.

George’s final American letters reveal conflicting emotions towards the “new” United States. In his formal address to parliament he announced, “Religion, language, interest, affections, may, and I hope will, yet prove a bond of permanent union between the two countries, to this end neither attention nor disposition on my part shall be wanting.”[34] In private, however, he was a little less gracious. When the treaty of Paris was signed, finally putting an end to the war in 1783, George churlishly commented, “I have no objection to that ceremony being performed on Tuesday; indeed I am glad it is on a day I am not in town, as I think this completes the downfall of the lustre of the empire; But when . . . public spirits are quite absorbed by vice and dissipation what has now occurred is but the natural consequence.”[35]

Yet in one final and perhaps surprising way the letters reveal George’s approach to the American war did have at least one positive and long lasting effect. There were many in Britain, including the Whig leader Charles Fox, who demanded an unconditional peace with America. This would have meant in effect abandoning the entire continent heedless of the diplomatic and military situation with the other bellicose nations of France, Spain, and Holland. Here George’s obdurate nature and insistence that independence must come with a guarantee of peace in Europe probably saved Canada as an independent nation. He astutely wrote, “common sense tells me that if unconditional independence is granted, we cannot ever expect any understanding with America, for then we have given up the whole and have nothing to [gain] for what we want from thence. Independence is certainly an unpleasant gift at best, but . . . must be [a] condition of peace.”[36]

In the end at least, his adherence to his mother’s advice had a positive effect on the history of at least two nations. In Great Britain and Canada, unlike America, for a further forty years George would still “be a King.”

[2]“Except at the Levees he saw nobody and nobody saw him.” Ibid., 5.

[3]Ibid., 4. Courtiers observed the adolescent Prince always “strove to follow the counsels she gave.”

[6]www.rct.uk/collection/georgian-papers-programme/papers-of-george-iii.

[7]Though George’s treatment of his numerous offspring is beyond the scope of this article, those wishing to study his turbulent relationship with his children should see John Van De Kirste, George III’s Children (London: The History Press, 2004).

[8]Dobree, The Letters of George III, 12.

[14]Dobree, The Letters of George III, 99.

[23]For the long running disputes between the City of London and George III over the American war which almost brought Britain to a constitutional crisis see John Knight, “King George III’s Twitter War,” Journal of the American Revolution, July 11, 2017.

[24]Dobree, The Letters of George III, 131.

[25]www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1754-1790/member/dunning-john-1731-83.

[26]Dobree, The Letters of George III, 136.

[30]King George to Lord Shelbourne, November 1782, in George Bancroft, History of the Formation of the Constitution of the United States Volume 2 (Clark, NJ: The Lawbook Exchange, 2000).

[31]www.englishmonarchs.co.uk/tudor_8.htm.

[32]Dobree, The Letters of George III, 154. George first threatened abdication in March 1782. He again wrote a draft abdication letter in March 1783. George spoke of “a cruel dilemma,”leaving him “but one step to take without destruction of my principles and honour; the resigning of my crown.”

8 Comments

Mr. Knight, you have researched and written a very insightful and interesting article. Where my research has touched on issues outside the field of intelligence, it became obvious to me that the British Government, and not only the King but also the bureaucracy, failed to understand, and indeed had no interest in understanding, that culturally the “Americans” had become a different breed of individuals from the British or for that matter the carefully suppressed Irish. This I see as perhaps the most important reason for the loss of the country. Your research supports my thinking.

Thank you for your article and more so the further reading links!

Great article, classic lust for power – Apparently the loyalty King George expected he failed to show his grandfather. – I am going to tell my mommy on you….

I strongly object to this article. For starters, Sir Lewis Namier showed long ago that the story of Princess Augusta saying “George, be a king” is a myth. Secondly, it is far too easy and far too common for modern historians to psychoanalyze George III based on spending zero seconds in his company. This has happened for decades with authors throwing around pejoratives on the king’s motives and actions. We did not know George III; we did not live in the 18th century; we do not understand what it meant to be a king at age twenty-two—which he was. The Hanover family was also not native to Britain, coming there only in 1714, and there had been an armed rebellion against the royal family in 1745–46, so he had a right to be suspicious of critics. Most importantly, George III was not a tyrant or acting inappropriately. If people in Alaska or Hawaii today used armed rebellion to attack American soldiers, because they wanted independence, the U.S. president and government would do exactly what the British government did in the Revolution: uphold the rule of law. George III was upholding the law as it existed at the time.

Punctuation counts. Is it “Be a King George”? or “Be a king, George” or .“George, be a king” Since a previous poster replied that Princess Augusta never said this phrase, I guess it doesn’t really matter now.

Thank you all for your comments and criticisms. This is what debating history is all about in my view. If there were only one opinion on historical “facts” sites like this would be pretty dull. I embrace all such criticisms, as if they are valid they can only improve my work. There are several points about your critique however Mr Monk that appear to me to be somewhat facile and in one case outright wrong.

It is ironic you quote Namier. As a former patient of Sigmund Freud, Namier was a believer and proponent of the psychohistory you later criticise and seem to despise. His work and sources were controversial at the time and have been largely disparaged since. Augusta saying to the young Prince “be a King George” was not a myth and is documented in contemporary accounts including that of his tutor Waldegrave.

Nowhere have I suggested George was a tyrant. On the contrary, I believe he was one of Britain’s greatest Monarchs. However, as pointed out by Ken Daigler he misunderstood the burgeoning nationalism of the American colonies and was the principal force behind the British political and military response to the rebellion. It is this that is the thrust of the piece. This, however, is my interpretation of his letters, is not definitive and is clearly open to challenge. This is your right.

However, your point that you need to have “known” “lived” or experienced the issues of George III to write about him seems a spurious argument to me. By definition, most history is written and debated by those who were not contemporaries. History would be a pretty cursory and dry exercise if only engaged in by those who had first-hand experience of the actions of, or attitudes of those written about.

I have recently written about the Great Fire of London but was never a baker on Pudding Lane, the first moon landing, but have never met Aldrin or been to the moon, and the England world cup victory in 1966 but have never played professional football in my life. I don’t think this in itself diqualifies me from writing about them.

Finally and most importantly, George III was NOT upholding the rule of British law as you state. As indicated in the piece, that law was the prerogative of the British parliament, not the British monarch and this is why he was castigated by so many British Whigs for his actions during the war. I look forward to reading your “non-Freudian” pieces in future. I am sure they will be informative and entertaining.

Mr Wright:

I enjoyed your approach to this article. More than a year later, however, I’m still puzzling over the beginning of your footnotes. “Ibid”” is used as scholarly shorthand to indicate that the current footnote was derived from the same source listed immediately before it. What was your source for the first five footnotes?

Unlike the print medium, in a format like this, even at a later date, the initial source might be popped in through a reply. I’ve had to do it myself.

Stephen Gilbert

Stephen Gilbert

Hi Stephen. A year pondering a footnote? Wow even in a pandemic years that is precisely 364 days too long. You are correct the note makes no sense. I have looked up the original script I sent to JAR and the beggining of the piece featured quotes from “You’ll be Back” the Lin Manuel Miranda “Hamilton” song. This had an original footnote number 1 which was – Bonamy Dobree (ed) The letters of George III Lonodn:Cassell 1935) George to Lord Bute 1756 pg 7. The ibid should therefore have referred to this source. I am assuming the editors either did not like my opening from “Hamilton” or using it infringed copy-right and in removing it they inadvertadly removed the original footnote too. Hope this helps.