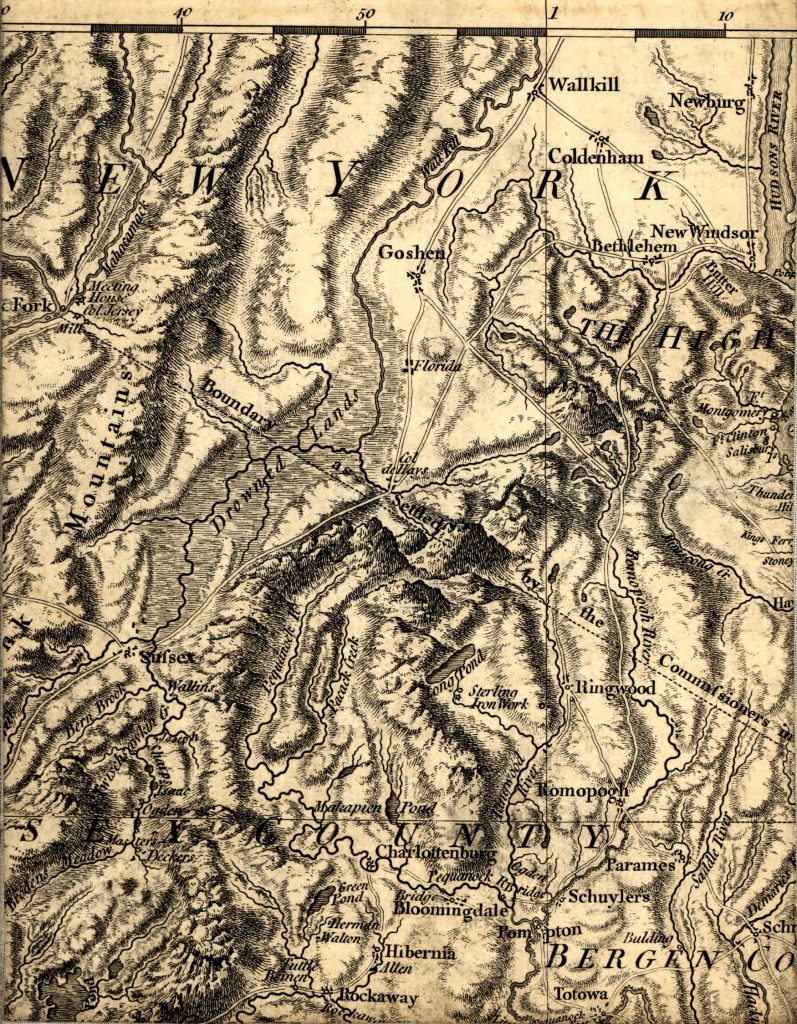

While there were many Revolutionary-era outlaws, Claudius Smith and the Cowboys of the Ramapos stand apart. Their story has long been exaggerated and romanticized through local legends, but the true account of their actions is far more violent. Smith and his band—comprised of his children, outlaws, deserters, Native Americans, and local Tories—terrorized the Whigs of Orange County in southeastern New York during the Revolution. The gang used beatings, robberies, and murder against combatants and noncombatants alike throughout the middle years of the Revolution, retreating into the dens of the Ramapo Mountains for safety. In committing these acts, the gang executed one of the era’s first and only campaigns of terrorism.

Claudius Smith was born on Long Island in 1736 and relocated with his family to Orange County, New York, near present day Monroe. In 1762 at the age of twenty-six, Smith enlisted in the Ulster County Militia under Captain James Clinton to fight for the British in the French and Indian War.[1] In the following seven years after the war, Smith’s criminal reputation grew. In 1769, a newspaper advertisement appeared in the New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury offering a fifty-dollar reward for Smith who recently escaped from jail after being confined for “debt, theft, and rioting.” The advertisement depicted Smith as having a white beard, pale complexion, short hair, and powder burns under his right eye. The newspaper warned that Smith went by the aliases James Reed and John Wright, and that he was “a great bully and will fight wherever he goes, being very conceited of his strength.” At the time of his escape, he wore raggedy clothes but would not for long, as he was a remarkable thief as well as “a noted horse stealer.”[2] Four years later, an advertisement in the New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury boasted that Newark, New Jersey, lawmen apprehended “the notorious Claudius Smith, who justly deserves to be rank’d among the first in his profession [horse stealing] in this country.” According to the advertisement, Smith escaped from prison four separate times because he had, “a dexterity peculiar to himself,” and added that he utilized multiple disguises to mask his crimes.[3]

When the Revolution came to Orange County, the once indiscriminate crimes of Smith and his gang became partisan acts of violence and thievery to the British government. They began by stealing horses in the area, penning them in an enclave known as Smith’s Clove near present day Monroe, New York, and delivering them to the British army in New York City.[4] Smith was captured once again in 1777 and imprisoned in Kingston, New York, for “stealing oxen belonging to the continent.” Upon his transfer to the jail in Goshen, Smith escaped.[5] On the night of October 6, 1778, Claudius Smith and the Cowboys raided the home of local militia captain Ebenezer Woodhull while he was away in Clarkstown, New York.[6] The following day, Abigail Woodhull testified to the Orange County Coroner that Smith and a party of six men came to her home, robbed her, and said that they wished Ebenezer were at home for they would “have him Ded or a Live.”[7]

Looking to satisfy their bloodlust that evening, Smith and the Cowboys continued to the house of another patriot, Maj. Nathaniel Strong. Mrs. Strong recalled to the coroner that around 1 a.m. the gang knocked on the door and broke the windows. When Major Strong asked who was at the door, Smith replied, “a friend,” and then ordered Strong to put down his gun and open the door. When Nathaniel complied and stepped outside, he was shot. Before he died, Strong named Claudius Smith as his killer.[8] Major Strong’s death prompted a letter of resignation from his brother Nathan Strong, a captain in the 4th New York Regiment of the Continental Army, as no one would be able to care for the family. Washington refused the resignation, but allowed the captain to return home and serve his time in the army as a supernumerary.[9]

The raid of the Woodhull residence and the murder of Nathaniel Strong by Claudius Smith and the Cowboys created a panic in the region. The following morning a group of seven local Whigs wrote to Governor of New York George Clinton with a summary of the gang’s crimes. They, too, articulated the paranoia of Orange County citizens:

In short, we have not thought ourselves secure for a long time. We live so scattered that they can come in the dead of night to any one family & do what they please.[10]

Eager to quell the local hysteria, Governor Clinton replied that he “issued such Orders as if vigorously executed trust will put a stop to these outrages in the Future.”[11]

With the exception of Claudius Smith’s escape to Long Island, Governor Clinton’s orders were ineffective. On November 11, 1778 the Cowboys ransacked Ringwood Manor, the home of local outspoken patriot and ironmaster, Robert Erskine, who was away serving as the Geographer and Surveyor General of the Continental Army. While no one was killed in the raid, the gang stole several hundred dollars worth of possessions and threatened to kidnap several of Ringwood’s residents “in his Majesty’s name.”[12] With local militias guarding the manor and bars placed over the doors and windows, attacking Ringwood Manor was a difficult task.[13] The Cowboys once again demonstrated that they could terrorize anyone supporting the Revolution in the Ramapo Mountains.

Around this time, a party of men led by Maj. Jesse Brush captured Claudius Smith on Long Island.[14] The party then transported him through Connecticut to Fishkill Landing in New York. Isaac Nicoll, the sheriff of Orange County, then took custody of Smith with the help of the Captain Woodhull and his militia. On January 13, 1779 the local court sentenced him to hang for his crimes of “burglary at the house of John Earle; robbery at the house of Ebenezer Woodhull,” and “for robbery of the dwelling and still-house of William Bell.”[15] Sheriff Nicoll expressed his feelings about Smith’s sentence to Governor Clinton four days later: “as to Claudius Smith and Jeames Gordon I shal Take pleashure in seeing them Executed.”[16] Smith was hanged on January 22, 1779.[17]

The intent of Claudius Smith’s execution was to rid Orange County of its most feared partisan and to reassure the region’s patriots of their safety. The result, however, was the exact opposite. John Clark was an ordinary citizen in Goshen, New York. He worked locally and occasionally served in the local militia like many of his neighbors. He likely did not expect Claudius Smith’s son, Richard, and the Cowboys at his door on the night of February 20, 1779, but after a knock he let the five or six men enter his home. One of the villains checked the time and declared: “it is about twelve o’clock and by one, Clark, you shall be a dead man.” They dragged him across his yard where Richard fired his pistol into Clark’s chest.[18] As he bled out, one man pinned this note to Clark’s coat:

A Warning to the Rebels

You are hereby warned from hanging any more friends to the government as you did Claudius Smith. You are warned likewise to use James Smith, James Flewelling, and William Cole well and ease them from their irons, for we are determined to hang six for one, for the blood of the innocent cries aloud for vengeance. Your noted friend, Capt. Williams and his crew of robbers and murders we have got in our power, and the blood of Claudius Smith shall be repaid. There are particular companies of us who belong to Col. Butler’s army, Indians as well as white men, and particularly numbers from New York that are resolved to be revenged on you for your cruelty and murders. We are to remind you that you are the beginners and aggressors, for by your cruel oppressions and bloody actions drive us to it. This is the first and we are determined to pursue it on your heads and leaders to the last till the whole of you is massacred. Dated New York February 1779.[19]

The murder of John Clark was the last, yet most incendiary act of terror committed by the Cowboys. As his report of the murder to Governor Clinton made clear, Sheriff Nicoll took the Cowboy’s threats seriously, expressing to Clinton that he was “a Fraid when the weather Gets warm and the Leaves Out, there will be many Murders Committed and Uppon some of Our principal peopal.”[20] Col. John Hathorn, a local militia leader, recalled that although Claudius Smith was dead, “his Baneful Poison” remains and warned that “Instances of their bloody acts are frequent, their threats obvious, insomuch that every Whig is realy in danger, its Notorious that no Individual that lives near their can be Exempt from their Power.” He added that a “number of the inhabitants are removing for fear and who dare even dare to keep their families on their places don’t pretend to Sleep in their Houses at Night.”[21]

It was the confessions of the aforementioned William Cole and another outlaw, William Welcher, that led to the Cowboys’ undoing. Sensing his end was near, the boastful Cole confessed to his crimes with the Cowboys, speculated as to who was responsible for the acts he was not involved with, and provided the names of Orange County residents known to harbor and aide the villains.[22] Divulging the Cowboys’ support system was disastrous for the group. General Washington himself began circulating the names of those mentioned in the confession, urging their immediate arrest.[23] The two confessions are essential, too, because they link the Cowboys to the British government in America and demonstrate that they were not just rogues but perpetrators of what today would be labeled state-sponsored terrorism. As proof, Cole claimed that the Ringwood manor thieves presented Mrs. Erskine’s gold watch to the Mayor of New York, David Matthews, and Robert Erskine’s rifle to Lord Cathcart, adding that Lord Cathcart awarded a bounty of 100 guineas to two of Claudius Smith’s sons for robbing the local muster-master. Cole also stated that many of the gang’s crimes were done with the help of either a detachment of British regulars or deserters. For instance, he claimed that last January, several Cowboys and “eleven of Gen. Burgoyne’s men” unsuccessfully ambushed a militia major in the Ramapos. William Welcher confessed his knowledge of a failed plot hatched by Mayor David Matthews, who offered 200 guineas each to kidnap the Governor of New Jersey, William Livingston.[24]

After the confessions of Cole and Welcher, the Cowboys committed no more notable violent crimes in the region for the remainder of the war. Some of the bandits likely dispersed into the mountains to avoid local authorities, but others were not so quiet. In a letter dated August 10, 1781, General Washington warned Governor Clinton that Richard Smith and several other Cowboys were promised “a very considerable reward if they will sieze your person and conduct you to New York,” though no records exist to indicate they even attempted the kidnapping.[25] Additionally, it is unclear who exactly was offering the reward.

The behavior of Claudius Smith and the Cowboys resembles the modern day definitions of terrorism. Using a hodgepodge of outlaws and ideologues, the gang acted independently but in support of the British government, and carried out orders and bounties provided by British officials. Though they robbed, murdered, and plotted against several of Orange County’s citizens, their goal was to generate fear in order to paralyze local anti-British activity, not simply to increase their wealth or eliminate enemies. They provoked a regional panic and forced the relocation of Patriot families as is demonstrated by the pleas of Sheriff Nicoll, Colonel Hathorn, and the committee of Whigs. Furthermore, they accomplished another desired result of terrorist groups: notoriety. Their crimes received wide circulation through newspapers, word-of-mouth, and personal correspondence to the point that even General Washington became aware of their conduct. Though the Cowboys’ terror failed to cause any major strategic or operational change for the Continental Army, it did create a problem that required an immediate response from Orange County’s civil authorities and militias. In the end, the lesson of Claudius Smith and the Cowboys is found in their transformation from petty criminals and outcasts to politicized mercenaries and killers. All they needed was a perceived threat to their existence, a common enemy, and a sense of purpose.

[1]New York Colonial Muster Rolls, 1664-1775: Report of the State Historian of New York, Vol. 2 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2000), 712.

[2]The New-York Gazette; and the Weekly Mercury, May 1, 1769, 3.

[3]Documents Relating to the Colonial, Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey, ed. William Nelson, Vol. 28 (Paterson, NJ: The Call Printing and Publishing Co., 1916), 564-565.

[4]Charles A. Huguenin,”The Cowboys of the Ramapos: The Legend of Claudius Smith,”, www.monroehistoryny.org/the-legend-of-claudius-smith–, accessed December 5, 2018.

[5]Edward M. Ruttenber and Lewis Clark, The History of Orange County, New York (Philadelphia: Everts and Peck, 1881), 71.

[6]The Public Papers of George Clinton: First Governor of New York, Vol. 4 (New York and Albany: State of New York, 1900), 146.

[9]Nathan Strong to George Washington, March 30, 1779, Founders Online, National Archives.

[10]The Public Papers of George Clinton, 146.

[11]The Public Papers of George Clinton, 147.

[12]James M. Ransom, Vanishing Ironworks of the Ramapos: The Story of the Forges, Furnaces, and Mines of the New Jersey-New York Border Area (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1966), 44-45.

[13]Albert H. Heusser, George Washington’s Map Maker (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1966), 152-53.

[14]New York in the Revolution as Colony and State, Vol. 2 (Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Company, Printers, 1904), 165. Major Brush was paid £480 for Smith’s capture.

[15]Ruttenber, The History of Orange County, 71.

[16]The Public Papers of George Clinton, 498. James Gordon was a convicted horse thief.

[17]Ruttenber, History of Orange County, 71.

[18]The Public Papers of George Clinton, 588.

[19]The New-York Gazette; and the Weekly Mercury, April 19, 1779, 2.

[20]The Public Papers of George Clinton, 587.

[21]”Letter From John Hathorn,” March 14, 1779, vol. 20F, pg. 29, Draper Manuscript Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, WI.

[22]Ruttenber, History of Orange County, 72-73.

[23]Washington to Thomas Clark, April 16, 1779, Founders Online, National Archives.

[24]Ruttenber, History of Orange County, 72-73.

[25]Washington to George Clinton, August 10, 1781, Founders Online, National Archives.

9 Comments

Interesting story of a vicious time in southern New York, but not necessarily “the era’s first and only” campaign of terror. Refer to the actions of Ethan Allen before the war started when, in 1773, he and his crew terrorized settlers in the New Hampshire Grants. He referred to it as “mob law” and “club law,” but in 1779 admitted that they had employed terror against them. Terror is also the term repeatedly utilized by New York authorities in describing their conduct when a proclamation went out authorizing their arrest in 1774.

As far as a definition goes, “terrorism,” one scholar recently defined, is “a performance art form.” It is “widely understood to be a political act, a gesture – however immoral or misguided – toward promoting some greater cause,” and “is primarily a spectacular method of communication aimed at audiences far from the target itself.” For “mob law” and “club law,” it was seen as the only viable alternative to counter the effects the common law had on those who disagreed with it.

For more, see my article in the Spring 2019 issue of Vermont History, which will be coming out in April, entitled “Law ‘at the muzzle of the gun’: Archaeology of a Fugitive Terrain, the New Hampshire Grants, 1749-1791.”

Mr. Shattuck,

Many consider the Boston Tea Party to fit the description of terrorism as a performance art as you’ve described. And too, it would be hard to dismiss much of Sullivan’s Expedition against the Iroquois as anything less than terrorism. One modern commentator provides the truism that the distinction between terrorism or a noble cause “depends on who is the agent.”

There are several of these instances throughout the war that could fit the ambiguous definitions of terrorism, which is why I wrote that the actions of the Cowboys constitute “one of” the first and only campaigns of terrorism.

Thank you for the comment!

Charles

If the Sullivan Expedition is labeled as terrorism, then some Indian raids should be considered terrorism too. Scalping and the killing of helpless infants certainly qualifies.

While society today debates just what is “terrorism,” I have never seen the term in a period document (I suspect it’s part of our modern love of labels). However, “terror” (occasionally, “terrour”) certainly saw use. In period dictionaries, it’s definition is quite basic–“fear communicated; fear received; the cause of fear.” In writings, it presents the sense of extreme fear–something more elemental than just fear. Isn’t that the goal of terrorism? Isn’t that what terrorism is?

Charles, I take care of the Woodhull Cemetery here in Blooming Grove—that of Captain Ebenezer, Abigail, and their children. (They are my first cousins, 7x removed.) I’m so glad to see you include them in your work. Some times Abigail’s contribution gets glossed over or lost. The DAR recognized her for patriotic service in regard to his trial. Thank you for including her here and keeping her memory alive.

Jill, I think Abigail’s testimony is a powerful display of courage and definitely one worth including.Thank you and I’m glad you enjoyed the article!

A great article. Thank you. Having lived in the are described in the article for all my life, I have heard some of these stories and a few others. The most interesting was that when Smith was hung (according to the stories he was very tall), his head came off. The story as told was that the head was placed in the foundation of the new Goshen Courthouse. True? Who knows? I also have hiked to ‘Smith’s Den’ in Harriman State Park many times.

The legend has it that Smith was 7 ft. tall but I’ve seen newspaper advertisements from the era that list him at 5 ft. 6/7 in. As to his head coming off and its display at the Goshen Courthouse, I’ve heard this is true.The Smith’s Den hike is definitely one I’d recommend! Thank you for your kind words!

Jill, where about is the Cemetery, and thanks for taking care of it. Do you have additional local history info?