Having just attained his thirteenth (or eleventh) birthday, he found himself confined to a bed on the second floor of a small two-story house on the Caribbean island of St. Croix, gripped by a violent fever now in its second week.[1] Next to him was his mother, who had been the first to come down with the illness shortly after New Year’s 1768.

The inheritor of a small fortune, Rachel Faucette had been pressured by her mother into marrying a silver-tongued “fortune hunter” by the name of Johann Michael Lavien.[2] The marriage had been “unhappy” from the start, and shortly after bearing him a son, she had left her husband—only to be imprisoned for months by virtue of a Danish law regarding deserting wives.[3] After being released, she had escaped to a nearby island and met the charming but indolent minor Scottish noble James Hamilton. The couple entered into a common-law marriage on the island of Nevis and would eventually have two sons, James Jr. and Alexander.

Looking to remarry, Lavien commenced official divorce proceedings a few years later. He accused Faucette of not only neglecting her lawful spouse and child, but of “whoring with everyone;” the court provided Lavien his divorce and also denied Rachel the right to remarry ever again—rendering the stigma of bastardy that had hung over James Jr. and Alexander permanent.[4]

Chafing under the difficulty of raising a family and at the complications presented by Rachel’s and the boys’ irregular status, James Hamilton abandoned his family a few years later, shortly after moving them to St. Croix.[5]

Stigmatized as whore and bastard, abandoned, and now desperately ill, Rachel and young Alexander had been subjected to the some of the worst examples of the cruelty and selfishness present in human nature.

Worse still, eighteenth-century medicine rendered the treatment for their shared fever harsher than the malady itself. Already drifting between death and life, mother and son were subjected to regular rounds of bleeding, enemas, and emetic purgatives for several days. In a horrific scene the modern mind can scarcely imagine, mother and son laid together in a sickbed saturated by their own sweat, filth, flatulence, and vomit as a result.

It was to be the last memory Alexander would have of his mother.

After two days of this agony, Rachel Faucette expired next to her son. Within hours of her death, officers from the local probate court descended upon the house to mark off all of Rachel’s property. Only just healthy enough to stand again, Alexander and his older brother would attend their mother’s funeral days later in clothing provided to them by the charity of others. What was left of Rachel’s estate would spend the next year held up in court, only to go to her ex-husband, who had wasted no time in swooping in to make his claims. The boys, now virtual orphans, were on their own.[6]

The trauma of his Caribbean childhood—and the attacks from opponents it engendered as a public figure—were an emotional scar that was reopened time and time again in Alexander Hamilton’s life. “I am a stranger in this country . . . ’Tis a weakness; but I feel that I am not fit for this terrestreal Country.”[7]

Hamilton’s origins also colored the way through which he viewed the world and human nature. Unsurprisingly, the lenses through which he looked at both were somewhat darker than rose.

Left to make it on his own merits, Hamilton almost immediately put his keen intelligence, acuity for figures, and flair for dramatic writing to good use as a clerk in a local merchant house. The precocious youth soon garnered the attention of wealthier patrons, who funded his permanent move to the colony of New York and admission into King’s College (now Columbia University). This was the first stepping stone in a career trajectory that saw him go from Patriot pamphleteer, aide-de-camp to George Washington, Continental Congressman, Constitutional Convention delegate, co-author of the Federalist Papers, to first Secretary of the Treasury in the Washington Administration.

From this last perch Hamilton arguably became the second most powerful man in the nascent republic. Never one to settle for doing one thing at a time when he could do two or three, the plans he submitted to Congress to put the new federal “machine in some regular motion”shocked many in their rapidity and reach.[8]

More importantly, they struck directly at the heart of the same ideological cleavages bitterly galvanized during the recentratification debate—between those who favored a national-centric, assertive central government and those who favored a state-centric, limited central government. Hamilton had always been one of the leading lights in the nationalist camp, and by virtue of his position and his proposals he was now the unquestioned leader of the burgeoning Federalist party.[9]

This also made him one of the two poles in the quickly-escalating political party system, opposed on the other side by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson. Not only would the latter become the leader of what was to become the Democratic-Republican Party in opposition to Hamilton’s national programs, but would clearly delineate an alternative conception of what the American Revolution had meant. More fundamentally still, Jefferson’s political organization would posit an understanding of human nature so distinct from Hamilton and the Federalists that the ensuing rancor between the two factions rendered that of our current discourse tepid in comparison.

The lenses through which Jefferson viewed mankind were as rosy as the fine wines he enjoyed at his dinner table.“I am among those who think well of the human character generally.” If freed from the superstitions and ignorance of past ages, and the monarchic urges of the modern age, human nature and the human mind were “perfectible to a degree of which we cannot as yet form any conception.”[10] It was—always had been, always would be—the higher calling of Jefferson and those with “true republican” principles to exhort mankind to “burst the chains under which monkish ignorance and superstition had persuaded them to bind themselves,”thereby enabling the “general spread of the light of science”and a golden, harmonious age of human history.[11]

Standing directly athwart this millennial aspiration, in the Jefferson imagination, was Alexander Hamilton, who would never reconcile himself to an open-armed embrace of republicanism, let alone democracy. Though he was “affectionately attached to the Republican theory,” and though its precepts were the “real language” of his heart, he could not cast aside grave doubts about it in practice; he considered its success after American independence “as yet a problem.”[12]

Having personally witnessed the lower-depths of human nature to a much greater extent than Jefferson, he was quite open in his belief that it was “not safe to trust to the virtue of any people.” Whereas Jefferson was convinced that severing ties with the constituted ways of the past was an absolute necessity, Hamilton could only tremble at such a prospect. “When the minds of [the people] are loosened from their attachment to ancient establishments and courses, they seem to grow giddy and are apt more or less to run into anarchy.”[13] For any order or liberty to exist, people must be restrained—by traditional ways and by constituted authority.

This was anathema to Jefferson, who would declare that a “precious degree of liberty” may run the risk of occasional “turbulence,” but that even this was inherently beneficial, as it “prevents the degeneracy of government, and nourishes a general attention to the public affairs.”[14]

Where Jefferson saw liberty, Hamilton saw license. Where Hamilton saw order, Jefferson saw tyranny.

Upon this fault line did the two men and their followers contest the battle to establish the meaning of the American Revolution: a Jeffersonian agrarian “empire of liberty” or a Hamiltonian single, commercial nation.[15]

Ostensibly, it was Jefferson and the Jeffersonian image of America that ultimately triumphed. Propelled by Federalist overreach (for which Hamilton himself deserves a lion’s share of the blame), he and the Democratic-Republicans’ won both the recently-constructed White House and convincing majorities in Congress in the Election of 1800.[16]

Assuming the role of valedictorian, Jefferson declared victory over not just the warm corpse of the Federalist party, but victory in the final, culminating battle of the American Revolution. His and the Democratic-Republicans’ triumph was “like the joy we expect in the mansions of the blessed,” and though the people of the United States had “been led hood-winked from their principles” during his predecessor’s administrations, he expected no less than “a perfect consolidation” of the revolutionary principles of ’76, and a perpetual “just and solid republican government maintained here.”[17] These would become “the true principles of the revolution of 1800, for that was as real a revolution in the principles of our government as that of 1776 was in its form.”[18]

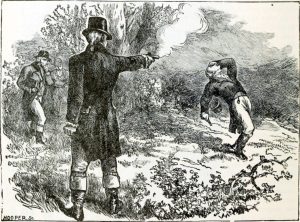

This ultimate victory became a symbolic fait accompli when Alexander Hamilton succumbed to the bullet of Vice President Aaron Burr in 1804. As meteoric as his rise to prominence, was Hamilton’s fall from grace once outside the moderating influence of George Washington’s supervision. From manipulating John Adams’s cabinet members from the outside, to publishing a disastrous pamphlet against Adams (and then working to unseat the president in the election of 1800), to the humiliation of the “Reynolds Affair,” to his open (and ultimately fatal) attempts to stymie Burr’s political career—the final decade of his life had been a seemingly-suicidal spiral downwards.[19] “We live in a world full of evil,” he lamented to his wife as he approached the last year of his life—seemingly resigned to the tragic fate soon to come. “In the later period of life misfortunes seem to thicken round us; and our duty and our peace both require that we should accustom ourselves to meet disasters with christian fortitude.”[20]

To all appearances, the “bastard brat of a Scotch Pedler” would end up not far from where he had begun: besotted in personal squalor and loss; a loser in life and in history.[21]

History, and its course, can be fickle though, and the Jeffersonian final victory over Hamilton would begin to look neither final nor victorious not long after the earth around the late Federalist’s grave had settled.

The issue that had caused the deepest lines of division between the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans had not been Hamilton’s assumption, bank, or manufacturing plans, but the French Revolution. As American ambassador, Jefferson had been present in Paris during—and had even participated in—the Revolution’s initial stages, and would remain an enthusiastic supporter, blithely assured upon his return to the States of its ultimate success.[22] “The nation has been awakened by our revolution, they feel their strength, they are enlightened, their lights are spreading, and they will not retrograde.”[23]

Not only was the revolution in France the logical heir to the one in America, it was destined to be every bit as successful. “I have so much confidence on the good sense of man . . . that I am never afraid of the issue where reason is left free to exert her force; and I will agree to be stoned as a false prophet if all does not end well in [France].”[24]

Hamilton had little to no confidence in the “good sense of man,” and had had forebodings towards the Revolution from the start. “I rejoice in the efforts which you are making,” he wrote to his old comrade, the Marquis de Lafayette, “while I fear much for the final success of the attempts . . . for the danger in case of success of innovations greater than will consist with the real felicity of your Nation.” Why such pessimism in a time of great hope? “I dread the vehement character of your people, whom I fear you may find it more easy to bring on, than to keep within Proper bounds, after you have them in motion.”[25]

Releasing, but then containing, popular energies during a revolution had been a concern of Hamilton’s at the outset of the American Revolution, and it was even more present at the outset of the French.[26] It came as little surprise then when the “cause of liberty” in France quickly devolved into The Terror—“the most cruel sanguinary and violent that ever stained the annuals of mankind, a state of things which annihilates the foundations of social order and true liberty.”[27]

Quick to denounce the course of events, Hamilton was even quicker to denounce those who continued to support the French Revolution in the United States (“our Jacobins”) despite its murderous devolution—Jefferson “the high priest”among them.[28] “In France . . . He drank deeply of the French Philosophy, in Religion, in Science, in politics.”[29] Still drunk from his time there, and upon his exalted views on human nature, Jefferson and his followers were too blind to see that the Revolution in France would lead, not to a new age of liberty, but to a sea of anarchic blood at worst; or to something akin to the old age of absolute monarchy at best.

Hamilton would not be far off the mark—on Jefferson’s delusion and upon the ultimate outcome. Though the latter would “deplore” those consumed by The Terror, he deplored their loss “as I should have done had they fallen in battle. It was necessary to use the arm of the people, a machine not quite so blind as balls and bombs, but blind to a certain degree.” In the end, “time and truth” would show that those lost to Madame la Guillotine had died for a greater purpose, and “their posterity will be enjoying that very liberty for which they never would have hesitated to offer up their lives.” In a sentiment that would have horrified Hamilton, Jefferson would conclude that “the liberty of the whole earth depended upon” the Revolution’s success, and rather than see it fail, “I would have seen half the earth desolated.”[30]

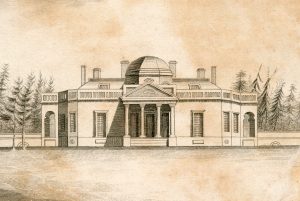

Yet ensconced in final retirement at Monticello years later, Jefferson would implicitly admit that history had indeed rendered him a “false prophet”—and that the late Alexander Hamilton had been correct all along. Far from being a vindication for the liberty of people everywhere, the French Revolution had instead become one of three epochs in human history defined by “the total extinction of national morality” and by Napoleon Bonaparte “partitioning the earth at his will, and devastating it with fire and sword.”[31] He had deplored the corruption and abuses of the Ancien Regime, but the revulsion he felt towards Napoleon brought forth the full extent of his ample descriptive powers: He was “The Attila of the age,” “the ruthless destroyer of 10. millions of the human race,” the “great oppressor of the rights and liberties of the world,” and his truly deserved fate would have been to perish “on the swords of his enemies, under the walls of Paris.”[32]

Even more galling to the elder Jefferson would be the disappointment of the younger Jefferson’s serene assurances about the United States’ own republican future—and, in turn, the confirmation of Alexander Hamilton’s skeptical premonitions thereof. The Louisiana Purchase that was concluded by his administration had doubled the territorial extent of the United States, and in so doing had, in Jefferson’s estimation at least, done nearly as much to ensure the republican future of the country as the revolutions of 1776 and 1800. “It is the case of a guardian, investing the money of his ward in purchasing an important adjacent territory,” he declared, and the addition of Louisiana was “a great achievement to the mass of happiness which is to ensue.”[33]

Hamilton was less sanguine. Believing the American people to be “more enterprizing than wise,” he and what were left of the Federalists worried that the westward migration to follow the Purchase “must not only be attended with all the injuries of a too widely dispersed population, but . . . must hasten the dismemberment of a large portion of our country, or a dissolution of the Government.”[34] Ever the nationalist, he prophesied that the greater the dispersion across the continent, the less influence the national government would be able to exert on its western people—and the less fealty those people would feel towards their government and country. The ultimate price of the Louisiana Purchase would not be $15 million dollars, but disunion.

Jefferson scoffed at this. “The larger our association, the less will it be shaken by local passions, and in any view, is it not better that the opposite bank of the Mississippi should be settled by our own brethren and children, than by strangers of another family?”[35] He was assured that history would show that “the larger the extent of country, the more firm its republican structure, if founded, not on conquest, but in principles of compact and equality.”[36]

To Jefferson’s increasing mortification, the advancing years would come to prove Hamilton’s forebodings prophetic once more. Through the first half of the nineteenth century, each new territory’s application for statehood triggered a sectional political war between southern and northern interests—between slave states and free—to the point that, by the time of the “Missouri question” in 1820, Jefferson was sounding an entirely different tune at the prospect of disunion. “But this momentous question, like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it as once the death knell of the Union.”[37]

Adding insult to the injuries already done to his assumptions about America’s future were the failures of the generations succeeding Jefferson’s and Hamilton’s—generations in which Jefferson had placed so much hope for so long. Vacating the stage of public affairs, he looked forward to resigning “everything cheerfully to the generation now in place. They are wiser than we were, and their successors will be wiser than they, from the progressive advance of science.”[38]

Yet by the time of the Missouri Crisis, he was resigned only to dying in the belief “that the useless sacrifice of themselves by the generation of 1776, to acquire self-government and happiness to their country, is to be thrown away by the unwise and unworthy passions of their sons, and that my only consolation is to be, that I live not to weep over it.”[39]

The agrarian republic he had always envisioned was slowly but surely giving way to the commercial, capitalist iteration Hamilton had foreseen, and for this the generation that had succeeded theirs was wholly to blame. This cohort,

having nothing in them of the feelings or principles of ’76, now look to a single and splendid government of an aristocracy, founded on banking institutions, and moneyed incorporations under the guise and cloak of their favored branches of manufactures, commerce and navigation, riding and ruling over the plundered ploughman and beggared yeomanry.[40]

Hamilton had not desired this so much as he had viewed it as inevitable, human nature being what it is. His harsh childhood in the Caribbean (and the harsh winter spent with the Continental Army at Valley Forge—and his experience with the mutinous Continental officers towards the end of the war—and his experience with the venality of parochial interests in the Confederation era) had disabused him of any belief in the inevitable “progress of science” or in human perfectibility. He had been born in, and never able to forget, the “vanity and vindictiveness of human nature,” and so he had spent his public life supporting plans and systems that had both taken into account and had harnessed those endemic defects in a productive direction.[41]

Jefferson’s first and lasting experience of human nature (an experience he tried to limit as much as possible within the secluded confines of Monticello) had been in the optimistic, abstract theories of the Enlightenment, encountered in the books his libraries had been lined with and through the modes and manners of the privileged Tidewater elite he was born and died in. It would be the consternation of his later years that the realities outside of this sheltered milieu consistently disappointed him—and confirmed the worldview of his greatest rival.

Hamilton’s political and mortal demise, brought about by his own endemic defects, deprived him of the opportunity to enjoy the satisfaction of witnessing his vision of America take shape—or the satisfaction of witnessing the Sage of Monticello’s consternation.[42] By the time history had begun to prove him right, he had been long-cold within his grave—but perhaps not quite so cold as the chill that increasingly gripped Thomas Jefferson’s heart the more he saw the Hamiltonian vision of the United States and the world develop before him.

The capricious winds of political fortune had given Jefferson final victory—but the irrepressible tide of history had given Hamilton final, albeit posthumous, revenge.

[1]For a discussion of the uncertainty regarding Hamilton’s year of birth, see “Happy Birthday Alexander Hamilton! But What Year Were You Born?” National Constitution Center, constitutioncenter.org/blog/happy-birthday-alexander-hamilton-but-what-year-were-you-born, accessed January 4, 2019.

[2]“To William Jackson, New-York Aug 26 1800,” in Joanne B. Freeman, ed., Hamilton: Writings (New York: The Library of America, 2001), 931.

[3]See Daniel S. Levy, “Trouble in Paradise: A Founding Father’s Island Youth,” in Neil Fine, ed., Alexander Hamilton: A Founding Father’s Visionary Genius—and His Tragic Fate (New York: Time Inc. Books, 2015), 14.

[5]See Richard Brookhiser, Alexander Hamilton, American (New York: Touchstone, 1999), 17.

[6]Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton (New York: Penguin Books, 2004), 24-25.

[7]“To John Laurens, Jany 8t.,” in Freeman, ed., Writings, 66.

[8]Alexander Hamilton to William Hamilton, May 2, 1797, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-21-02-0037.

[9]For an authoritative analysis of the reaction to and debate of Hamilton’s programs, see Stanley Elkins and Eric McKitrick, The Age of Federalism: The Early American Republic, 1788-1800 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 257-302.

[10]“To William Green Munford, Monticello June 18, 1799,” in Jean M. Yarbrough, ed., The Essential Jefferson (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2006), 194.

[11]For Jefferson’s “true republican” quote, see Thomas Jefferson to Peregrine Fitzhugh, February 23, 1798, Founders Online,National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-30-02-0089. For his declamation against “monkish superstition, see “To Roger C. Weightman, Monticello, June 24, 1826,” in Yarbrough, ed., Essential Jefferson, 277.

[12]“To Edward Carrington, Philadelphia May 26th, 1792,” ibid., 750.

[13]“To John Jay, New York Novem 26. 1775,” in Freeman, ed., Writings, 44.

[14]“To James Madison, Paris, Jan. 30, 1787,” in Yarbrough, ed., Essential Jefferson, 156.

[15]For Jefferson’s idea of an “empire of liberty,” see Jefferson to Benjamin Chambers, December 28,1805, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/99-01-02-2910.

[16]For a discussion of the final death throes of the Federalist Party during the presidency of John Adams, see Elkins and McKitrick,The Age of Federalism, 691-754. Though Jefferson’s and the Democratic-Republicans’ victory in 1800 was a convincing landslide, Jefferson’s personal election as president was not made official until after one of the most dramatic episodes in American political history. See Edward J. Larson, A Magnificent Catastrophe: The Tumultuous Election of 1800, America’s First Presidential Campaign (New York: Free Press, 2007).

[17]“To John Dickinson, Washington, March 4, 1801,” in Merrill D. Peterson, ed., Jefferson: Writings (New York: The Library of America, 1984), 1084.

[18]“To Judge Spencer Roane, Sept. 6, 1819,” in Yarbrough, ed., Essential Jefferson, 250.

[19]For a sketch of Hamilton’s last decade, see Brookhiser, American, 127-153, and 197-217. For a detailed examination of the “Reynolds Affair,” see John L. Smith, ”Alexander Hamilton’s Extramarital Escapades.” Journal of the American Revolution. August 28, 2016, allthingsliberty.com/2016/08/alexander-hamiltons-extramarital-escapades/.

[20]“To Elizabeth Hamilton, March 1803,” in Freeman, ed., Writings, 995.

[21]John Adams to Benjamin Rush, January 25, 1806, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-5119.

[22]For Jefferson’s recollections of his experience with the French Revolution, see Peterson, ed., Writings, 78-97. For an analysis of Jefferson’s time in Paris, see Joseph, J. Ellis, American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson(New York: Vintage, 1998), 125-138.

[23]“To George Washington, Paris, Dec. 4, 1788,” in Peterson, ed., Writings, 932.

[24]“To Diodati, Paris, About 1789,” ibid., 958.

[25]“To Lafayette, New York October 6th. 1789,” in Freeman, ed., Writings, 521.

[26]See aforementioned letter, “To John Jay, New York November 26. 1775,” ibid., 44.

[27]“Memorandum on the French Revolution,” ibid., 835.

[28]For his denunciation of those who continued to support the Revolution in America, see “American Jacobins, [1795–1796],” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-19-02-0122. For his “high priest” label, see “The Stand No. VII, [21 April 1798],” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-21-02-0242.

[29]“To Edward Carrington, Philadelphia May 26th, 1792,” in Freeman, ed., Writings, 746.

[30]“To William Short, Philadelphia, Jan. 3, 1793,” in Peterson, ed., Writings, 1004.

[31]“Autobiography, 1743-1790, With the Declaration of Independence, January 6, 1821,” ibid., 93.

[32]“To John Adams; Monticello, July 5, 1814,” ibid., 1339.

[33]“To John C. Breckinridge; Monticello, Aug. 12, 1803,” ibid., 1139; “To Dr. Joseph Priestley; Washington, Jan. 29, 1804,” Ibid., 1142.

[34]“Purchase of Louisiana,” in Freeman, ed.,Writings, 999.

[35]“Second Inaugural Address; March 4, 1805,” in Peterson, ed., Writings, 519.

[36]“To Francois de Marbois; Monticello, June 14, 1817,” ibid., 1410.

[37]“To John Holmes; Monticello, April 22, 1820,” in Yarbrough, ed., Essential Jefferson, 254.

[38]“To Judge Spencer Roane, Sept. 6, 1819,” ibid., 252.

[39]“To John Holmes; Monticello, April 22, 1820,” ibid., 255.

[40]“To William Branch Giles; Monticello, Dec. 26, 1825,” Ibid., 271. For a sketch of the disappointments and disillusions of Jefferson’s later years, see Geoff Smock, “Jefferson’s Reckoning: The Sage of Monticello’s Haunting Final Years.” Journal of the American Revolution. April 25, 2018, allthingsliberty.com/2018/04/jeffersons-reckoning-the-sage-of-monticellos-haunting-final-years/.

[41]“The Defence No. I,” in Freeman, ed., Writings, 844.

[42]For a discussion of the contrasting visions of America the two men had, see Chernow, Alexander Hamilton, 3-6; and James H. Read, “Alexander Hamilton’s View of Thomas Jefferson’s Ideology and Character,” in Douglas Ambrose and Robert W.T. Martins, eds., The Many Faces of Alexander Hamilton: The Life and Legacy of America’s Most Elusive Founding Father (New York: New York University Press, 2006), 77-103.

9 Comments

Hamilton’s vision lives on to current day as we continue to prove this brilliant man’s prophecy true as to the spite and avarice of our souls.

“Jefferson would implicitly admit that history had indeed rendered him a “false prophet”—and that the late Alexander Hamilton had been correct all along.” Outstanding essay Mr. Smock!

Very well written and thought out. Great summation of both men and very accurate.

I wish there was a like button or a huzzah button. Lots of times I don’t want to comment but really want to show support for the post and JAR.

An excellent suggestion, IMO, I like the “huzzah button” idea.

Agree with comments. First-rate article and writing.

According to my research, Alexander Hamilton had a family secret. He was the hidden son of the British-American/Dutch power elite having descended from Peter Stuyvesant through his biological family – the Crugers of NYC. He was the son of businessman Henry Cruger, Sr., of the British West Indies and the City of New York. The nephew of New York Mayor John Cruger, Jr., the grandson of Mayor John Cruger of New York who had married heiress Maria Cuyler of Albany, New York. Hamilton was therefore the step-brother of Henry Cruger,Jr. of New York and Bristol, who had the unique distinction of having been elected to both the Parliament of Great Britain and the New York State Senate. Until this aspect of Hamilton’s history is known, Hamilton will continue to remain an enigma.

Great article. I have such a hard time with the Hamiltonian v Jeffersonian views of government, but this well written and illuminating piece about Jefferson’s predictions vs actual outcomes.

This was an excellent article, IMO. I believe that it would make a perfect primer for a college level course in any of several fields of study – American History, Political Science, Psychology, Sociology, Philosophy, and, in particular, Divinity studies since it addresses the paradoxical affects of the Yin/Yang of the human animal. Looking at our beloved country today, the expression, “and so it goes …” seems apropos.