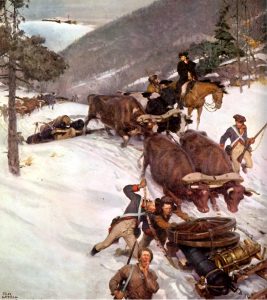

The best-known scene of Col. Henry Knox’s train of artillery in the winter of 1775-1776 is Tom Lovell’s painting The Noble Train of Artillery. It shows a caravan of ox-drawn artillery that the Continental Army moved from the recently conquered Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York (pictured near the top left of the painting) through the snowy Berkshire Mountains in western Massachusetts to where they were needed most: Gen. George Washington’s siege lines outside of Boston. The painting probably depicts a young and thin Knox on horseback to the right. The guns were necessary for Washington to establish sufficient fields of fire over Boston town, thereby putting the besieged British there in an inferior position and thus forcing the end of a stalemate that had gone on since April 19, 1775. With these guns overlooking Boston, on March 17, 1776, the last of the British evacuated the city, ending a near eleven-month siege.

Knox’s Noble Train became deservedly famous given its instrumental role in ending the British occupation of Boston and giving Washington his first victory of the war. Yet there is one major flaw with this story and the many variations of its depiction: it did not happen. Or, at least, it did not happen as depicted. For in truth, Knox did not have oxen. So then why do many of the sources and pictures say otherwise?

Let’s start at the beginning. . . .

The Need for Artillery

In the spring of 1775, the British attempted to raid a militia weapons cache outside Boston. Shots were fired, the countryside militia swarmed the British, and after a daylong running battle, the British found themselves besieged in Boston.

Boston bookseller Henry Knox managed to escape the siege lines, however, and began serving as a volunteer aide to the top militia commander, Massachusetts Gen. Artemas Ward. Knox had spent many idle hours in his Boston-based The London Book-Store reading up on the art and science of artillery, but when the Battle of Bunker Hill came sixty days into the siege, on June 17, 1775, Knox served as little more than a messenger for the ailing General Ward, who was suffering that day in his Cambridge headquarters from a debilitating fit of “calculus” (probably a bladder stone). The British won the battle, but it served only to extend their lines and the siege continued.

George Washington soon arrived and took command of the militias of the various colonies represented there, and from these he began to form the new Continental Army. Washington quickly realized breaking the siege and forcing the British out of Boston would require heavy artillery. (Thus far, all he had were a few light field pieces, probably mostly 4-pounder cannon.)

Meanwhile, just before the Battle of Bunker Hill, Benedict Arnold of Connecticut (commissioned at time as a colonel in the Massachusetts service) and Ethan Allen of the New Hampshire Land Grants (later Vermont) led a small force in seizing the two ill-defended British forts of Ft. Ticonderoga and Ft. Crown Point, both on Lake Champlain in eastern New York. In taking these forts, the Americans had gained a considerable supply of large artillery, including several cannon and mortars. The trouble was getting these guns back to the siege lines outside Boston. In the end, strife between Arnold and Allen delayed the transportation of the artillery back to Boston indefinitely.

As the Siege of Boston continued for months, Washington at first set his attention on digging in, expanding fortifications, and organizing his new Continental Army. The topmost Massachusetts artillerymen, the elderly Col. Richard Gridley, determined to retire, influenced in part by the courts martial of two of his artillery officer sons because of their lackluster service in the Battle of Bunker Hill.[1]Still, Washington had hoped that Gridley would serve as the Continental Army’s new artillery commander. Those artillery officers next in succession felt themselves too old to take on the burdens of command, and instead wholeheartedly supported the relative unknown Henry Knox. Washington agreed to Knox’s selection, but final authority on this resided with the Continental Congress, away in Philadelphia.

With the end of the year upon him, Washington grew more anxious to take the offensive against the British in Boston, though with so few cannon and so little gunpowder, he hardly had the means to act, even in a defensive posture. So, without waiting for Congress, on November 16, Washington asked Henry Knox to depart for Ticonderoga and fulfill the plan laid out by Benedict Arnold so many months earlier: to collect from Fort Ticonderoga all the artillery pieces he could and transport them back to American lines outside Boston. As Washington implored, “the want of them is so great, that no trouble or expence must be spared to obtain them.”[2]

Knox set off immediately, first to New York City to inventory the artillery supplies there, and then on to Ft. Ticonderoga. Though Knox would not learn of it for some time, on the next day, Congress indeed resolved to commission Knox into the Continentals with the rank of colonel.[3]

Knox’s Ticonderoga Expedition

On December 5, Colonel Knox arrived at the former British Ft. Ticonderoga and took inventory of the artillery pieces. Those guns from neighboring Ft. Crown Point were apparently brought to Ticonderoga before his arrival. Of the mortars, Knox selected fourteen of various sizes, most of which were average, though he must have been elated to find the three iron 13-inch mortars, short but massive, perhaps a ton each. For cannon, he could only find one large brass 24-pounder, but he was able to find thirteen 18-pounders plus ten 12-pounders. These plus other smaller cannon gave him forty-three pieces total, some brass, some iron. He also collected two howitzers, both of 8-inch caliber. There were many artillery rounds available, though Knox did not collect these. Instead, most would come from a different route, cast or otherwise stolen from the King’s store in New York.[4](Gunpowder would in time be made by the colonies, but a large supply came from the seizure of British stores in New York.[5])

To get this “Noble train of Artillery,” as he called it, to Boston, Knox first had to transport the pieces by gondola a short distance on Lake Champlain and then by land to nearby Lake George.[6]There the guns were loaded onto three vessels: a scow, a large batteau, and a periauger (that Knox called a “Pettianger”). The scow was at first overloaded and sank in the low water, but Knox’s hired men managed to “bail her out and tow her to the leward shore . . . and by halling the cannon aft ballanc’d her, and now she stands ready for sail.”[7]The three vessels were then sailed or rowed southward to the decommissioned Fort George at lake’s end. From there, Mother Nature came to his aid. A storm poured on them an “exceeding fine Snow” some two feet deep, which allowed his hired New York crews to mount the artillery onto sleighs. However, the snow proved too deep at first, and there was trouble securing oxen at a fair price.[8]

Before departing from Fort George to go ahead of his Noble Train to Albany, Knox wrote to Washington on December 17, 1775, claiming he had “provided [for?] eighty yoke of Oxen to drag them [the sleighs of artillery] as far as Springfield.”[9] On the same day, he wrote a similar sentiment to his wife Lucy Flucker Knox: “We shall cut no small figure in going through the Country with our Cannon, Mortars, etc., drawn by eighty yoke of oxen.”[10]

This image is now deeply rooted in American memory, captured in paintings, but it is far from reality. It seems Knox wrote of this plan too soon.

Once in Albany, where he visited at the home of Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler, Knox began negotiating in earnest for those oxen he had written about. The oxen were necessary to bring the artillery sleighs down from Fort George to Albany and then eastward back toward Boston.

In his diary, Knox gives the following during the month of December:[11]

26th. Sent off for Mr. [George] Palmer to Come immediately down to Albany.

28th. Mr Palmer Came Down. & after a considerable degree of conversationbetween him & General Schuyler about the price the Genl offering 18s. 9d. & Palmer asking 24s. prday for 2 Yoke of Oxen. The treaty broke off abruptly & Mr Palmer was dismiss’d. By reports from all parts the snow is too deep for the Cannon to set out, even if the Sleds were ready. [Which they were not, as they had no beasts to pull them.]

29th. General Schuyler agree’d with [me]. Sent out his Waggon Master & other people to all parts of the Country to immediately send up their slays [sleighs] with horses suitable, we allowing them 12s. prday for each pair of horses or £7 prTon for 62 miles.

The 31st, the Waggon master return’d the Names of persons in different parts of the Country who had gone up to the lake [George] with their horses in the whole amounting to near 124 pairs with Slays, which I’m afraid are not strong enough for the heavy Cannon, if I can Judge from the same shown me by Genl Schuyler.

In careful reading, we find that, after a negotiation for oxen failed based on price, Colonel Knox relented to using horses instead, of which he acquired at least 124 pairs.[12]In fact, there is evidence that Knox originally intended to use horses, until the oxen deal became an option, and so he merely fell back on his original plan.[13]

And so, contrary to tradition, it seems Knox had few oxen on his journey. The famous paintings and illustrations are both quite wrong.

Meanwhile, the artillery remained near Ft. George, delayed not just because of a lack of beasts, but also because of weather. The land route southward from the fort was an exceedingly slow one that followed the Hudson River, and once the crews were finally underway, they were forced to cross the frozen Hudson four times before reaching Albany.

Here Knox’s diary tells of another misconception of his Noble Train of Artillery. Not only was the artillery transported mostly by horses for the remainder of its journey, but also it was not one long caravan as commonly pictured. Rather, it was a fragmented set of companies, sometimes miles apart, conducting their respective sleighs with teams of two or sometimes up to eight horses (only occasionally employing oxen, whenever they could be had), and at times augmenting these with additional beasts as necessary to surpass particularly high snow drifts or difficult terrain.

As a few artillery pieces finally came into Albany, one at a time, the snow at first continued to fall, but then Mother Nature forsook them. A “cruel thaw” for several days delayed the Noble Train as it tried to make its way into town.[14]But snow soon fell again, and with it, Knox’s train was again on the move.

From Albany, Knox’s train passed eastward over the Berkshires, from “which we might almost have seen all the Kingdoms of the Earth,” and so into Massachusetts. This was the most difficult part of the journey, and here the horses at times proved insufficient for pulling the heavier pieces over the mountains. Knox continued to seek out oxen to augment his horses, but only occasionally did he find any to hire. At least he did hire “two teams of oxen” on January 11, 1776.[15]

Once over the Berkshires, the rest of the Noble Train’s journey continued without much difficulty. The artillery began to arrive in Framingham, some twenty miles outside Boston, on about January 25. With the exception of some of the lighter pieces which were immediately sent to the lines and mounted in the American entrenchments, most of the pieces were probably kept in Framingham until Washington called them up in early March in what would result in a bloodless American show of force that ultimately led to the British Evacuation of Boston on March 17, 1776.[16]

Conclusion

So why are the stories wrong? As we have seen, the Noble Train of Artillery was primarily dragged by horses. The many history books that report oxen likely only researched the subject in the papers of George Washington, citing the letter there from Knox that gives his intentions to use oxen to drag the train. But in truth, after local teamsters tried to price-gouge Knox for use of their oxen, Knox decided to use horses instead, yet apparently never wrote of this change to Washington. And since the correction does not appear in the papers of George Washington (and historians did not utilize Knox’s incomplete diary), historians therefore never identified the change of Knox’s plan. Thus, the wrong story of Knox’s oxen spread. In truth, Knox’s expedition was pulled by horses.

[1]Derek W. Beck, The War Before Independence: 1775-1776 (Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2016), 351-53 (Appendix 5).

[2]The instructions are a bit more complicated than given here. Instructions to Knox, November 16, 1775, in Papers of George Washington (PGW), rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/GEWN.html.

[3]Gridley’s official departure and Knox’s selection in Journals of the Continental Congress, ed. Worthington Chauncey Ford (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904),November 17, 1775, 3: 358-59, books.google.com/books?id=OTQSAAAAYAAJ.

[4]Enclosure to Knox to Washington, December 17, 1775, which gives just thirty-nine cannon including six 12-pounders. The other four 12s were obtained at the last minute, and Knox to Washington, January 5, 1776, describes them. Both are in PGW. Some of the pieces selected were originally from Crown Point (cf. Enclosure to Arnold to Mass. Comm. of Safety, May 19, in Peter Force’s American Archives (Washington, DC: M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, 1837-1846), 4: 2: 645-46). However, Knox’s diary, December 5-9, 1775, gives no mention of him going to Crown Point, so they must have been brought down before his arrival. “Knox’s Diary during his Ticonderoga Expedition,” New England Historical and Genealogical Register (1876), 30: 323, books.google.com/books?id=97IUAAAAYAAJ.

[5]Beck, War Before Independence, 305.

[6]Knox to Washington, December 17, 1775, in PGW; “Knox’s Diary,” December 5-9, 1775, 323. By land: the narrow and overly shallow waterway connecting the two lakes would have been frozen by this time. Knox’s diaryreferences a bridge.

[7]“Knox’s Diary,” December 9, 1775, 323. Scow sinks: Knox to his brother William, December 14, 1775, in Alexander C. Flick, “General Henry Knox’s Ticonderoga Expedition,” New York State Historical Association Quarterly Journal 9 (Apr 1928), 119-35.

[8]“Knox’s Diary,” December 25?, 26, 1775, 323-24.

[9]Knox to Washington, Fort George, December 17, 1775, inPGW.Ft. George was at the south end of Lake George, about fifty miles north of Albany.

[10]Knox to Lucy Flucker Knox, December 17, 1775, in Flick, “General Henry Knox’s Ticonderoga Expedition.”

[11]“Knox’s Diary,” December 27-31, 1775, 324.

[12]Knox’s diary also reports that the artillery was not transported from Ft. George to Albany until after this negotiation (due to a heavy snow, not just a lack of transportation), and thus was indeed brought by horse-drawn sleighs. Sadly, a few pertinent pages of Knox’s diary are lost. Interestingly, George Palmer also connived his way into a contract to produce for Knox a number of carriages or sleighs, which Knox later realized he had no need of because there were plenty existing sleighs available for hire. Yet Palmer firmly pressed Knox to honor the contract. It is unclear whether those sleighs Knox ultimately employed were indeed those built under Palmer’s contract. On this, see George Palmer to Knox, December 25, 1775, in Flick, “General Henry Knox’s Ticonderoga Expedition.”

[13]Knox’s December 10 Instructions for their [Artillery] Transportationin Flick, “General Henry Knox’s Ticonderoga Expedition.”

[14]Knox to Washington, January 5, 1776, PGW.

[15]“Knox’s Diary,”January 10, 1776, 325. Two ox teams: Knox, “Diary,”January 11, 1776, ibid.

[16]General source for this essay: “Knox’s Diary,” 321-26. On the date of Knox’s arrival, not recorded in his diary, instead: Flick, “General Henry Knox’s Ticonderoga Expedition.” The overall story is given extensive discussion in Beck, War Before Independence, 301ff.

21 Comments

Thomas Mifflin took umbrage at all the credit Knox received for this feat, claiming that most of the burden fell on his shoulders (as Quartermaster General) and that he too should have at least shared in the laurels. Curious if his role in all this figured at all in Knox’s account, because this was supposedly the start of Mifflin’s disillusionment with Washington’s generalship and his utter distaste for the role he (Mifflin) had in the Quartermaster Dept.

I did not see Mifflin’s name come up in Knox’s documentation, but to be fair, Knox’s documentation is incomplete.

Thanks for including Benedict Arnold in the taking of Ft Ti. Too many in history give 100% credit to Ethan Allan, and that marked the beginning of a long list of insults that resulted in Arnold’s decision to become a turncoat. Not justified, but now better understood ….

I actually don’t understand why Ethan Allen is so well remembered. After Ft Ti, he tries to take Montreal almost single-handed and is captured by the British. This after the Green Mountain Boys ousted him as their leader, replacing him with Seth Warner.

“For cannon, he could only find one large brass 24-pounder, but he was able to find thirteen 18-pounders plus ten 12-pounders. These plus other smaller cannon gave him forty-three pieces total, some brass, some iron.”

This is exceedingly unusual. Rarely was brass used for big guns. It was prized for its toughness and relative light weight, so it was usually reserved for field artillery. The weight of big fortress guns didn’t matter, so iron and bronze were primarily used. Not a single bronze gun is mentioned above. This is singular in itself, as most of the guns I’ve seen from Fort Ticonderoga were either iron or bronze. In fact, as bronze guns were generally prized over iron, if there was a choice between two guns of the same caliber, one bronze the other iron, they’d always go for the bronze one. Bronze and brass are different alloys based on copper, bronze being tin, brass being zinc. Is it possible Knox didn’t know the difference? (The main difference between the two was that when a bronze gun failed it usually burst by rupture or splitting. Iron on the other hand would blow apart in lethal chunks. The choice for an artillerist was a no brainer.)

In the eighteenth-century artillery, the term “brass” was applied to what we would now specify was bronze.

What JL Bell said 🙂

I grew up in Springfield Mass and loved to see the monument (near I-91) that commerates this fantastic journey.

J.L. Bell, thank you. Clears that up.

As someone who loves cattle, horses, and the Revolution, I found this article to be catnip. Of course I am fascinated to learn that the famous paintings are wrong. However I’m wondering why Knox changed from oxen to horses.

Perhaps I am misreading it, but it appears to me that Palmer was asking 24s per day for two yoke of oxen. Around here, a yoke of oxen is two oxen. Two yokes = four oxen. Therefore, each pair cost 12s.

Henry Knox dismissed Palmer and his oxen, and sent out for horses. He paid 12s for each pair.

Oxen are slower but stronger than horses, cheaper to feed, easier to keep, and their cloven hooves help them in the snow (especially if shod for ice).

Instead of 80 pair of oxen, it appears that at the same price per pair Henry hired 124 pair of horses, and still had to fall back on hiring oxen or extra horse teams to pull sleds up some of the steeper hills. If this is true, he did not save any money at all.

Why would he have done this? Might it have been because he was from Boston and had little knowledge of cattle? Even a city kid would have had a passing familiarity with horses.

Or maybe Henry wrote “2 Yoke of Oxen” when he meant a single double-yoke, i.e. two oxen. In that case, each yoke of oxen would have been 24s, and he (I think?) saved about £21 minus the cost and aggravation of locating the extra pulling help, and minus the extra feed and horse care.

All of this has been great fun for this part-time farmer to think about. Thank you.

It looks like availability was a more important factor than cost. The local farmers weren’t offering their ox teams in droves (!), but there was a contractor ready to supply horses. And Knox was on a deadline.

Thanks, that’s what I suspected also, after Palmer’s original offer was turned down. I also wondered if Schuyler’s price was a fair one for a more settled area, but not for a sparsely populated one, where an ox team would be difficult to replace. It takes 4-5 years to raise and train a team, so letting one go to Knox would be like giving up one’s farm tractor for the foreseeable future.

I appreciate both of your insights 🙂

Though they may have paid the same price per day for oxen and horses, as you noted horses were faster. A team of oxen averaged between 6 and 8 miles a day. A team of horses around 12 miles a day. (Though I don’t know how well this formula would have applied to the available roads.) So even if the oxen were the same price per day, the horses could theoretically get the job done somewhere between half and two-thirds the time. Thus the oxen were that much more expensive, or less economical, than the teams of horses. So the price is misleading since it doesn’t take into account the anticipated length of the trip.

This is great insight. I love your thinking. I wonder if the opposite is true through some of the more rugged terrain. Do you think the oxen would’ve gotten the job done quicker through the Berkshires? And, not given in the article above, one heavy gun broke through the ice near Albany, and they spent the better part of a day trying to pull it back out. Maybe oxen there would’ve made the job quicker?

All great points. Here’s another thought.

Something I have noticed in advertisements is that most horses of the period were small, what today we would call large ponies (14.2 hands). It is a selling point when ads claim “nearly 15 hands!” (an inch or two over pony size.) I’m confident that Henry Knox was not renting animals resembling modern giant drafts, but small, wiry animals. A horse/pony this size weighs about 900+ lbs. An ox’s greater strength is partly due to greater weight and muscle (1200-1800 lbs). So which animal would get the job done faster would depend on what quality was most needed: strength or speed? In deep snow or rugged hills, it would be strength. On clear roads, it would be speed.

You definitely know more about horses than I. My only thought is that the paintings seem to generally show large horses. For instance, Washington was a tall man, and his horse seems appropriately large. I recall too in some notes about William Dawes, who was one of the forgotten riders ahead of the April 19th 1775 start of the war, that he had a larger horse. I don’t know the history of horses, but my gut is that there were ample large horses for such an expedition even in 1775-1776. As more circumstantial evidence, when I see clothing of the period, most of the men were in the ranges of sizes as men are today, at least in height (not girth). Such makes me think that the horses were probably similar to today as well.

A lot depends on how cold it was. If it were a deep freeze, then the condition of the roads wouldn’t matter much, since their surface would have been frozen solid (as good as paved). Top it off with several inches of snow and the sleds would have moved right along regardless of what was pulling them. (The hard part would have been going down-hill.) And, of course, as we all know from sledding, the first few that pass create a good slick surface for the ones that follow. Horses would have had as good traction as oxen, and most pulling horses of the region may have even been provided with winter shoes that grab the ice… especially for traveling along rivers. One reason there was privation at Valley Forge, for example, was because it was actually a mild winter. If it had been good and cold the roads would have frozen solid providing a hard surface. Instead, because of the mild weather the supply wagons were mired in mud up to the hubs of their wheels.

Some information regarding a minor point–namely, going down hill in the snow and ice. There are at least three things you can/could do: have a braking bar like a bobsled; if the sled has front and rear runners, take the rears off and let the back drag on the ice; or sling a slack chain side to side in front of the runners and let them ride up on it causing the chain to dig into the ice.

At several points in his diary, Knox wishes the weather were colder and snowier. Winter was, after all, the season when New Englanders usually moved logs and other heavy items to the ports because of the snow-packed roads.

All great conversation, thanks for the insights again!