Catharine Sawbridge was born in Wye, Kent, England to John Sawbridge and Elizabeth Wanley on April 2, 1731. Her father was a landed proprietor; her mother was an heiress. She was the their second child. She had an older sister Mary and two younger brothers, John and Wanley. Catharine’s education was left to a governess after the death of her mother when she was two years old. It appears that her education occurred on two levels: the first from the governess who, according to John Sawbridge, was “ill-qualified for the task she undertook;”[1] the second from her curiosity. In her father’s library, history caught her attention. She became an avid reader of “those histories that exhibited Liberty in its most exalted state, the annals of Roman and Greek Republics . . . Liberty became the object of a secondary worship.”[2] Later in life, she described this early period in the third person to her friend, Benjamin Rush: “A thoughtless girl till she was twenty, at which time she contracted a taste for books and Knowledge by reading an odd volume of some history, which she picked up in a window of her father’s house.”[3]

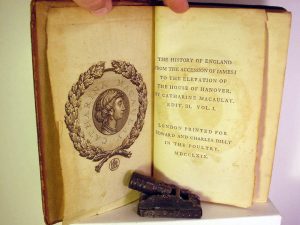

On June 18, 1760 at the age of twenty-nine, Catharine married a Scottish Physician, Dr. George Macaulay, who was fifteen years her senior. They lived for the next six years at St. James Place in London until his death. It was during these six years that Catharine Macaulay began to write her multi-volume History of England from the Accession of James I (1603) to that of the Brunswick Line. Volume I was published in 1763. In the Introduction, she explained why she chose to write the History:

Patriots who have sacrificed their tender affections, their properties, their lives, to the interest of society, deserve a tribute of praise unmixed with any alloy . . . Party prejudice, and . . . party interest, have painted past times in so false a light, that it is with difficulty we can trace features, which if justly described, would exalt [these] worthies . . . the virtue of [these] characters . . . is the principal motive that induced me to undertake this intricate part of the English history.[4]

Applying the lessons learned from the decline of the Roman Republic, she sought to show the parallel issues that characterized the reign of the House of Stewart. Her Whig version provided a counterpart to David Hume’s Tory-leaning version of the same period. Thomas Hollis, a fellow Whig republican, made available to her tracts and pamphlets from the 1640s and 1650s that had never been previously used by any other historian. Because there were no public libraries in London, a historian had to have access to personal libraries, and men like Hollis were all too ready to make them available to Macaulay. Aside from David Hume and Dr. Samuel Johnson, her work “was received with great applause.” Hollis wrote, “the history is honestly written, and with considerable ability and spirit; and is full of the freest, noblest, sentiments of Liberty.”[5] Dr. Joseph Priestley recommended “the very masterly history of Mrs. Macaulay.”[6] John Wilkes referred to Macaulay as “that noble English historian who does so great an honour to her own sex.”[7] Jonathan Mayhew, in a letter to Thomas Hollis, wrote that Mrs. Macaulay wrote “with a Spirit of Liberty, which might shame many great Men in these days of degeneracy, and tyrannysm, and oppression.”[8] Benjamin Franklin, in a letter to a newspaper, wrote about those “honest set of writers . . . who always show their regard to truth . . . to . . . the infinite advantage of all future Livies, Rapins, Robertsons, Humes and McAulays who may be sincerely inclin’d to furnish the world with that rara avis a true history.”[9]

Shortly after its publication Macaulay and her brother, John Sawbridge, became acquainted with John Wilkes. Unlike her brother she never became an active supporter of Wilkes, but they maintained a mutual admiration of each other. The reason: Macaulay was more of a political polemicist while her brother was more a political strategist.

In 1766 George Macaulay died at the age of fifty. It was also the year that Volume II of her History[10] was published. At the same time, she began to spend a considerable amount of time with the “Real Whigs” led by Thomas Hollis. They were a group of republican dissenters who saw themselves as descendants of the Commonwealth men (ie. Milton, Locke, Sidney, Harrington, etc.) of the seventeenth century. The more she discussed with, debated, and challenged her new friends’ positions, the more she crystalized her own position. She believed that man had natural rights and freedoms, that government was created to protect those rights and freedoms, and that when government denies or obstructs those rights and freedoms, man is justified to alter, rebel against, or abolish the government. In her History she attempted to show that true liberty was built upon virtue, the willingness of men to give up their private interests for the common good of society; and that Independence was the unwillingness of men to be constrained by the arbitrary (or unrestrained) powers of government. Self-government and the rule of law were for her the basis and expression of independence. Self-government was built upon representation and office rotation. “That as democratical power never can be preserved from anarchy without representation, so representation never can be kept free from tyrannical exertions on the rights of the people without rotation”[11] and the rule of law relied on the consistency of its application—which was difficult to maintain with the existence of the King’s prerogative. Macaulay’s first two volumes covered the reign of James I and the beginning of the reign of Charles I. Volumes III and IV, published in 1767 and 1768, covered the reign of Charles I until his death.

After finishing medical school in Edinburgh, Benjamin Rush travelled to London in September 1768 to practice at Middlesex Hospital and St. Thomas Hospital. He spent considerable time at the New York Coffee Shop of publishers Edward and Charles Dilly. Sometime in early January 1769 at a dinner at the Dilly’s home, Rush met Macaulay. A couple of weeks later, he wrote to her with a question regarding a position she had taken in her fourth volume:

you propose that “the representative assembly should not have the power to imposing taxes till the subject has been first debated by the senate.” Give me leave to observe here that I Cannot help thinking that the assembly should retain the exclusive right of taxing to themselves. They Represent the greatest part of the people. They are . . . from all parts of the commonwealth and are therefore much better acquainted with the circumstances of the country. Besides, they . . . are naturally supposed to have more property in the state, and therefore have a better right to give it away for the purposes of government. [12]

Not long afterwards, Macaulay received a letter from the Earl of Buchan. In it he wrote, “I have seen a letter from A Young American within these few days of the name Rush . . . He gives a long Account of a Conversation you honor’d him with . . . You stand Very high in Mr. Rush’s opinion”[13] From this first meeting, Macaulay and Dr. Rush would go on to be lifelong friends and correspondents.

In the same year, Macaulay wrote her first political pamphlet. It was entitled Loose Remarks on Certain Positions to be found in Mr. Hobbes’s Philosophical Rudiments of Government and Society with a Short Sketch of a Democratical Form of Government. It was addressed to Pasquale Paoli, the Corsican general, who was leading a revolt against France. In it, she challenged the belief that monarchies were necessary because of the flaws in human nature. She offered advice for constructing a republican constitution: “Of all the various models of republics, which have been exhibited for the instruction of mankind, it is only the democratical system, rightly balanced, which can secure the virtue, liberty, and happiness of society”[14] And she encouraged the enactment of additional reforms.

John Almon, a London publisher, distributed James Otis, Jr.’s Vindication of the British Colonies in the spring of 1769. Otis was one of the two firebrands in Boston—the other was Samuel Adams. In April, Macaulay, after having read the pamphlet, wrote to Otis,

Your patriotic conduct and great Abilities in defence of the rights of your fellow Citizens claim the respect and admiration of every Lover of their Country and Mankind . . . I beg leave to assure you that every partizan of liberty in this Island sympathizes with their American Brethren: have a strong sense of their Virtues and a tender feeling for their sufferings, and that there is none among us in whom such a disposition is stronger than in myself . . . The principles on which I have written the history of the Stuart Monarchs are, I flatter myself, in some measure correspondent to those of the Great Guardians of American Liberty.[15]

She ended the letter, “I shall be very glad to have the Honour of an account from your own hand of the present state of American affairs.” Three months later, she received the following reply:

Were I equal to the business [that you request] it would require an album. At present I can only say No. America is really distressed . . . The governors of too many of ye Colonies are . . . unprincipled . . . [and] rapacious revenue officers in general are to the last degree oppressive.[16]

This was the last communication that Macaulay would ever receive from Otis. Shortly after this letter, he was attacked by a Boston custom-house official because of a newspaper article he had written. The official beat Otis, who “received many very heavy blows [from a cane] on his head . . . that instantly produced a discharge of blood.” [17] For the remainder of his life, James Otis, Jr. was to suffer long bouts of mental instability. Otis’s sister Mercy Otis Warren informed Macaulay what had happened to her brother. This began another lifelong friendship and correspondence.

Beginning in 1770, Macaulay informed some of her American friends that she thought of continuing her History up to and through the colonial war. This encouraged many of them to send to her manuscripts, pamphlets, books, newspapers, summaries of colonial debates, and resolutions.

On March 30, 1770, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia wrote to Macaulay. He had never met her or written to her in the past.

A Lady of your singular merit, may expect to be troubled with the admiration, and the gratitude, of every friend to . . . freedom, in every part of the world. All the works of Providence . . . deserve admiration; . . . This Madam, is the only apology, that a stranger removed 3000 miles from you, has to make, for the liberty he has taken of writing this letter, and of presenting you with a late edition of [Henry Brooke’s] Farmer [Letters] published in this Colony. Your fine understanding, and your strong attachment to the rights and liberty of mankind, will secure your approbation of the worthy writer.[18]

Six days later, he wrote to his brother Arthur who was stationed in London, “I have not yet got Mrs. Macauley’s history—Will you be pleased to purchase it for me, and any other of her works that may be published.”[19]

The first incident in the American colonies that Macaulay responded to was the Boston Massacre. In a note of condolence to the Committeemen of Boston, dated May 4, she wrote,

I think myself much honored by the town of Boston for the compliment of transmitting the narrative relative to the massacre perpetrated by the ministry on the 5th of March. In condoling with you on that melancholy event, your friends find a considerable alleviation in the opportunity it has given you of exhibiting a rare and admirable instance of patriotic resentment tempered with forbearance and the warmth of courage with the coolness of discretion.[20]

The next day, her second political pamphlet, Observations on a Pamphlet, entitled, ‘Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontent,’ was published. It was a response to Edmund Burke’s pamphlet Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontent in which he claimed that the present discontent between England and her American colonies was due to the absence of a single-party government and to a “system of favouritism” in the present government. Macaulay, on the other hand, claimed that

A system of corruption began at the very period of the [Glorious] Revolution, and growing from its nature with increasing vigor, was the policy of every succeeding administration. To share the plunder of a credulous people, cabals were formed between the representatives and the ministers. Parliaments . . . from controling power over the executive parts of government, became a mere instrument of regal administration.[21]

Horace Walpole in his assessment of the two wrote “Mrs. Macaulay’s principles were more sound and more fixed than Burke’s, and [her] reasoning was more simple and more exact.”[22]

John Adams wrote Dissertations of the Canon and Feudal Law in 1765. It appeared in the Boston Gazette in four parts. In 1768 Thomas Hollis reprinted the work, also in four parts, in the London Chronicle. Because the name of the author did not appear in the Boston Gazette, it likewise did appear in the London Chronicle. For more than a year Macaulay had been corresponding with Sarah Prince-Gill, the wife of Moses Gill, a Whig merchant in Boston. Macaulay having read the serial in the Chronicle wished to learn the name of the author. She wrote to Prince-Gill and asked her to look into it for her. On March 24, Prince-Gill wrote back,

If Madam You will excuse a Liberty prompted by zeal for the Common Cause, I wou’d just hint that the Author of the “Dissertations on the Cannon & Feudal laws, is Worthy your Correspondence If you chose to maintain one in Boston . . . the real author is John Adams Esq; Barrister at law in Boston: A gentleman of Clear Sense, Precision of Sentiment and Expression, and thoroughly awake to the Cause of Liberty . . . [also] the assistance of the noblest patriots in Boston with whom I have the honor of a personal acquaintance will not be wanting whenever you make a requisition (for manuscripts, pamphlets, books, etc. . .).[23]

With this letter, Prince-Gill included a copy of her father’s History of New England.

Sometime over the summer, Moses Gill, on behalf of his wife, approached John Adams and informed him that Catharine Macaulay wished to open a correspondence with him. On August 9, he took the first step:

Madam . . . I have read, not only with pleasure, and instruction, but with good Admiration, Mrs. Macaulays History of England. It is formed upon the Plan, which I ever wished to see adopted by Historians. It is calculated to Strip off the false Lustre from worthless Princes and Nobles and Selfish Politicians, and to bestow the Reward of Virtue . . . upon the generous and worthy only . . . I could not therefore but esteem the [invitation] given me by Mr. Gill, as one of the most agreeable & fortunate occurences of my life . . .[I] have, however been informed that you have in contemplations . . . [decided that] the affairs of America are to have a share . . . it would give [me] infinite pleasure . . . if [I] can by any means in [my] power, by Letters or otherwise, contribute any Thing to your Amusement, and especially to your Assistance in any of your Inquiries.[24]

Isaac Smith, Jr., a twenty-two year old cousin of Abigail Adams, visited England early in 1771. While there he was to deliver two letters for John Adams.

Your letter, sir, I delivered to Mess. Dilly, who have both treated me with the greatest kindness and complaisance. I have had the pleasure of meeting with Mrs. McAulay, at her house; who enquired of me with regard to you, and informed me, sir, that she should write to you, as soon as she published a fifth Vol. which she has now in her hands.[25]

Shortly after Isaac Smith’s letter reached the Adams home, Abigail Adams wrote back to him with a request:

I have a great desire to be made acquainted with Mrs. Maccaulays own history. One . . . so eminent on a tract so uncommon naturally raised my curiosity . . . to know what first prompted her to engage in a Study never before in England to the publick by one of her own Sex and Country . . . As you have been entroduced to her acquaintance, you will I hope be able to satisfie me with some account.[26]

Macaulay, having finished Volume V, kept her promise and wrote to John Adams. She complimented him on the quality of his Dissertations and accepted his invitation to carry on a correspondence. “A correspondence with so worthy and ingenious a person as your self Sr. will ever be prised by as part of the happiness of my life.” [27] By this time men like John Adams and Benjamin Rush were sending over to Edward and Charles Dilly and John Almon everything that was published of significance in the colonies. This provided Macaulay with the most current information for consideration.

Richard Marchant, the Attorney-General for the colony of Rhode Island, was sent to London in July 1771 on legal business. There he met Arthur Lee, John Wilkes, John Price, and Benjamin Franklin, and frequented the New York Coffee Shop. He unfortunately never got to meet Thomas Hollis who had recently moved to the countryside. On April 29, 1772, at the weekly gathering in her home, Lee introduced Marchant to Macaulay. He described the visit in his journal:

I saluted this amiable daughter of Liberty with inexpressible Pleasure, nightened by the Pleasing Manner in which she rec’d me. We had a Feast of about two Hours Conversation upon Liberty in Genl The situation of the National affairs of the Kingdom which to Her appear fast approaching to Dissolution by the very Means which some there think the greatest Proof of Her Stability.—She enquired much of American Affairs. . . Her Spirit rouses and flashes like Lightning upon the Subject of Liberty, and upon the Reflexion of any Thing noble and generous—she speaks undaunted and freely lets forth her Soul—and disdains a cowardly Tongue or Pen [28]

Marchant met with Macaulay five more times before departing for the colonies. At the last meeting he gave her a copy of his pastor, Ezra Stiles, Sermon on the Christian Union. Upon his return to Rhode Island, Marchant delivered a letter from Macaulay to Stiles.

By the Favor of Mr. Marchant in whose company I have been very happy during some time of his Stay in England I am acquainted with the eminent abilities of the Author of the Discourse on the Christian Union. I take the opportunity of Mr. Marchant’s return to America to send you Sir thanks for the pleasure which the perusal of that Performance gave me and to request it as a favor that you will give a place in the Redwood Library to my Publications as a small Testimony of my Regard.[29]

Like with Benjamin Rush, John Adams, and Mercy Otis Warren, this would open another lifelong correspondence.

In six years Macaulay had written four volumes, two political pamphlets, established correspondence with a number of significant colonists, battled with male conservative historians regarding her abilities, and buried a husband she loved. She was worn out and had become ill. On July 19, 1771, she informed John Adams she had been suffering “with a severe fever for five month” and sometime between July 17 and 19, 1772, Henry Marchant reported, “she is in a very infirm State of Health through long confinement.” The illness would cause her to relocate to the city of Bath with its warm springs and peaceful countryside a couple of years later. Beginning in 1773, Macaulay turned much her attention to the impending conflict in the American colonies.

[1]Mary Hays, Female Biography (London: Richard Phillips, 1803), 5: 288.

[2]Catharine Macaulay, History of England from the Accession of James I to that of the Brunswick Line (London: J. Nourse, 1763), 1: vii.

[3]George W. Corner, ed., The Autobiography of Benjamin Rush (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1948), 61.

[4]Macaulay, History of England, 1: viii-ix.

[5]Francis Blackburne, Memoirs of Thomas Hollis (London: J. Nichols, 1780), 1: 210.

[6]Joseph Priestley, Lectures on History and General Policy (London: J. Johnson, 1803), 1: 340.

[7]John Almon, ed., Correspondence of the Late John Wilkes with his Friends (London: R. Phillips, 1805), 4: 139.

[8]Jonathan Mayhew to Thomas Hollis, August 8, 1765, in “Hollis-Mayhew Correspondence,” Bernhard Knollenberg, ed., Massachusetts Historical Society Proceedings 69 (1956), 173.

[9]“A Traveller, 20 May 1765,” in Leonard W. Labaree, The Papers of Benjamin Franklin (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1967), 12: 135.

[10]Macaulay, History of England, Vol. 2.

[11]Catharine Macaulay, Observations on a Pamphlet, entitled, ‘Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontent,’ 2nd edition (London: Edward and Charles Dilly, 1770), 20.

[12]L. H. Butterfield, ed., Letters of Benjamin Rush (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1951).

[13]www.gilderman.org/content/catharine-macaulay-14.

[14]Catharine Macaulay, Loose Remarks on certain Positions to be found in Mr. Hobbes’s Philosophical Rudiments of Government and Society with a Short Sketch of a Democratical Form of Government, 2nd edition (London: W. Johnston, 1769), 29.

[15]Catharine Macaulay to James Otis, Jr., April 27, 1769, in The Warren-Adams Letters (Boston, MA: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1917), 7-8.

[16]www.gilderlehrman.org/content/catharine-macaulay-40.

[17]London Chronicle, November 4, 1769.

[18]www.gilderlehrman.org/content/catharine-macaulay-12.

[19]Richard Henry Lee to Arthur Lee, April 5, 1770, in The Letters of Richard Henry Lee, 1762-1778, James Curtis Ballagh, ed. (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Archives), 1: 41-5.

[20]Letter to Gentlemen of Boston, conveying her condolence about the Boston Massacre, May 4, 1770, Catharine Macaulay, Boston Public Library, American revolutionary War Manuscripts, Collection (Boston:1902).

[21]Macaulay, Observations on a Pamphlet, 10.

[22]Horace Walpole, Memoirs of the Reign of George III (London: Richard Bentley, 1845), 4:130-1.

[23]www.gilderlehrman.org/content/catharine-macaulay-42

[24]John Adams to Macaulay, July 9, 1770, in The Adams Papers, Papers of John Adams,September 1755 –October 1773, Robert J. Taylor, ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1977), 1: 248.

[25]Isaac Smith, Jr., to John Adams, February 21, 1771, in The Adams Papers, 1: 71-74; “The American Interests of the Firm E. and C. Dilly, with Their Letters to Benjamin Rush,” L. H. Butterfield, ed., Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America (1951), 45: 305-09.

[26]Abigail Adams to Isaac Smith, Jr., April 20, 1771, in The Adams Papers, 1: 76-78.

[27]Macaulay to John Adams, July 19, 1777, in The Adams Papers, 1: 250.

[28]Journal Entry, April 29, 1772, Henry Marchant Letter Book, Newport Historical Society, Newport, RI.

[29]Franklin Bowditch Dexter, ed., The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901), 1: 293

5 Comments

I truly enjoyed your brief treatise regarding Mrs Catherine Macaulay. You paint a very good picture of her and her love of Liberty and Democratic principals.

However, one is left wondering about Mrs. Macaulay, left on her sick bed. What could have happened to her?

Please continue her story – it is fascinating!

Yes, Mrs. Macaulay’s second marriage and how people seized on it as a way to minimize her is a dramatic story in itself.

Glad you enjoyed the article on this remarkable woman, Craig. The rest of her story is coming soon!

You left us hanging! So, she turns her interest to the impending war; does she keep writing, does she go to America?

You will write more won’t you?

KarenP

Part 2 has already been submitted.

Thanks for letting me know that the article caught your interest.