The period of the American Revolution does not afford many accounts of individual rank and file soldiers’ exploits, particularly on the side British side. The filing of some 80,000 pension applications in the United States makes it much easier to learn of a soldier’s activities during the war, whether it be the mundane task of guard duty or the dangers of battle. There was no equivalent pension for British or Provincial veterans. The British method of reward was meant for long-serving or wounded soldiers of the army. Those so “recommended” received the benefit of the Chelsea Hospital in London, where a veteran could be an out-pensioner and simply receive a stipend living somewhere on his own, or an in-pensioner, residing at the hospital, complete with rations, clothing and lodging. Pensioners could also be called upon again for military service, typically in “invalid companies” serving in a fortress or garrison town somewhere in Great Britain, and typically for a limited duration.

In addition to soldiers of the established regiments of the British Army, Chelsea also admitted militia, new-raised British corps (regiments raised after the start of the war and disbanded at its conclusion) and in some cases Provincials (regiments raised in America consisting primarily of Loyalists). Between the years 1778 and 1784, some 10,834 soldiers were admitted as out-pensioners, the vast majority at the end of the war, when there was a general reduction in the size of the army.[1] Scattered among the pensioners were a small number of Provincial soldiers, including twenty-two men of the Queen’s Rangers. Ten more of the Rangers were admitted over the next five years.

The Queen’s Rangers was one of the first Provincial regiments raised in the New York City area upon the arrival of the British forces there in July 1776. The corps was initially commanded by Lt. Col. Robert Rogers, the famed ranger commander from the French and Indian War.[2] Rogers gathered a number of diverse characters together to raise the companies that would compose the corps, including Robert Cook, a Loyalist from Wrentham, Massachusetts, who found himself (briefly) a prisoner of the rebels just three days after hostilities commenced at Lexington and Concord.[3]

The Provincial Forces were soon after put under the supervision of Inspector General Alexander Innes, former secretary to Lord William Campbell, the royal governor of South Carolina. Innes had the unenviable task of regulating what amounted to a small army of amateurs, both soldiers and officers, into something approaching the quality of the British Army. The Provincials were to be paid, armed, clothed, fed and disciplined in the same manner as the Regulars, which led Innes to observe on March 14, 1777: “Negroes, Mulattoes, Indians and Sailors, have been enlisted, shall they be discharged, and orders given none in future be admitted?” The answer was an unequivocal yes, commanding they “be discharged and none to be hereafter enlisted on any account.”[4]

For the Queen’s Rangers, this was just one in a series of events that completely altered the corps late that winter. Unhappy with Robert Rogers and the bulk of his officers, Alexander Innes, with the blessing of the commander in chief of the British Army in America, Sir William Howe, set about replacing Rogers and his officers.[5] Among those affected was Capt. Robert Cook, one of the ousted officers, and his men, apparently all black. The point may have been virtually moot, if a deserter’s description from March 2, 1777 was accurate: “Captn. Cook’s Company of Negroes are (all but three or four) dead.”[6]

The changes led to a series of new commanders for the Rangers, all British Army officers, culminating in October 1777 when John Graves Simcoe, an officer “with Confessed Ability, & very distinguished Honor” was appointed commandant.[7] Simcoe, only twenty-five years old when he took command, had arrived in America in 1775 as a lieutenant in the 35th Regiment before being promoted to a captaincy in the 40th Regiment. By the summer of 1778, the new British commander in chief had promoted him to lieutenant colonel, back-dating his commission to July 1, 1776 so as to give seniority over all other Provincial officers of that rank.[8] Simcoe was clearly a rising star in the British Army.

Under Simcoe’s command and active leadership, the Queen’s Rangers would see extensive service on the outposts of the British Army, particularly in Westchester County, New York, and in New Jersey. The corps also grew and expanded in scope, adding a troop of cavalry along with light artillery and riflemen, making it a formidable corps of light infantry. The Rangers under Simcoe took part in such actions as the Battle of Monmouth and in repelling General Lord Stirling’s attack on Staten Island; they set sail in April 1780 to take part in the final stages of the Siege of Charleston, South Carolina.[9]

Arriving towards the end of operations (the city surrendered to the British on May 12, 1780), there was little for Simcoe and his men to do but await further orders and explore the countryside. Simcoe wrote to his friend John André, “We hunt & barbecú in a grove of laurels to morrow, I wish business would permit you to partake of what I expect a novel Pleasure.”[10] In addition to fine dining, Simcoe and his men secured several black slaves from the plantations and ranks of the enemy. “I understand Mrs. Elliot is to apply to the Comr. in Chief for four Negro boys now with the Queens Rangers, & I think it necessary to explain to this matter,” Simcoe once again wrote to André, continuing “The Boys are Taylors & Musicians, & are at this time clothed in the Rebel Artillery Uniform, which her Husband commanded.”[11] This was no doubt a reference to the late Lt. Col. Barnard Elliott, commander of the 4th South Carolina Regiment, an artillery unit.

Simcoe found use in other former slaves as well, most notably for intelligence gathering. One unnamed young African American was sent by Simcoe to André to be de-briefed; Simcoe wrote to André, the deputy adjutant general, “I send you a very intelligent Negro Boy, within the Circle of his knowledge — When you dismiss him I will be obliged to you to pass him to the Quarter House, as I mean to keep him.”[12]

So who were these young former slaves collecting around Simcoe, and what role could they play in an organization like the Queen’s Rangers that was officially barred from enlisting blacks as soldiers? The muster rolls of the regiment may provide some answers. In the Provincial Forces, muster rolls were made out once every sixty-one days and were created for the purpose of paying soldiers. The rolls themselves listed all the soldiers by company, noting things such as dates of enlistment and casualties (deaths, desertions, and discharges) over that period. Regrettably, the muster period covering the return of the corps to New York, April 25 to June 24, 1780, does not appear to exist. The one immediately after, however, seems to include some of the men alluded to by Simcoe. While blacks were not allowed to bear arms, some few did serve in other capacities: principally as pioneers (unarmed military laborers) and as drummers or musicians. Each company of men had at least one drummer, often two, with perhaps some fifers. Their job was to communicate signals to the troops in camp, on the march and in battle. Comparing the rolls from before and after the siege, new drummers appear on the rolls with names that suggest they may be among the men Simcoe mentioned to André.

One new drummer appeared in Capt. John Saunders’ company, listed as “John Carolina.” Other than an annotation that he was born in America, no personal information was listed.[13] Capt. McCrea’s company had two new drummers, both Americans, Richard Lockerman and Barney Hartley.[14] The company commanded by Capt. James Kerr had one as well, but being absent sick and not mustered, was listed simply as “A Black Musician Name Not remembered.”[15] Andrew Ellis, another American-born drummer, was listed in Capt. Stair Agnew’s company.[16] Perhaps most interesting was the Highland Company under Capt. John Mackay, who added a hornsman or “clarinet” by the name of Sampson.[17] Were all these drummers black? Perhaps, perhaps not. They do appear to have included the captured slaves of the Ellis family, not all of whom worked out in their new capacity. Captain Kerr eventually remembered that his drummer’s name was Hector Young, “A Black boy intended for the Musick; but found unfit & taken from the Strength 16 Sept. 1780.”

Were these all of them? Apparently not.

A 1789 certificate from Lieutenant Colonel Simcoe sheds light on the subject, but also some confusion: “That the negroes Barney and Andrew served as Bugle Horns in the Queen’s Rangers, from the Siege of Charlestown to the disbanding of that Corps. That Andrew is in Nova Scotia & Barney in London & upon Col. Simcoe’s Enquiry of him, he said, that both Andrew & himself belonged to Mr. [John] Izard, who at the Time they joined the Queen’s Rangers, was aid du Camp to the Rebel General [Isaac] Huger.”[18] Andrew was indeed Andrew Ellis, who at the end of the war was a trumpeter in Capt. David Shank’s troop of light dragoons in the Queen’s Rangers.[19] The corps had undergone a major expansion starting in 1780, with new troops of light dragoons (cavalry) being raised by Captains John Saunders, David Shank, and Thomas Ives Cooke; later they added a troop of hussars formerly commanded by Capt. Frederick de Diemar.[20] If what Simcoe stated was accurate, that Ellis and Barney had been the property of John Izard and not the Elliotts, they could not have been among the four boys mentioned to André as being used as musicians. And who was Barney?

The certificate referenced above, dated February 25, 1789, appears to coincide with a request made by Simcoe to the War Office on March 20 following. The Queen’s Rangers, along with four other Provincial battalions, were made regular regiments of the British Army on December 25, 1782, so there was no question that, as British soldiers, men of the Queen’s Rangers were eligible for Chelsea pensions provided they met the accepted criteria.[21]

Determining the identity of Barney took some sleuthing, aided by Simcoe’s letter to the War Office recommending the young black trumpeter:

Sir,

B E Griffiths has applied to me for his Discharge from the Queens Rangers. The Particulars of his Situation I take the Liberty of Submitting to you, & entreating the Protection of the War Office on his behalf.

He joined the Queens Rangers at The Siege of Charles Town, & was very useful as a Guide; He served as a Dragoon & was frequently distinguished for his Bravery & Activity—in particular at the action near Spencer’s Ordinary, by his presence of mind when sentinel, He was principally concerned in betraying the Enemy into an unfavourable [situation], & in the consequent Charge of Cavalry was distinguished by Fighting hand to hand with a French Officer who commanded a Squadron of the Enemy & taking him Prisoner. When the Cavalry afterwards charged the Rebel Infantry, He by his gallantry preserved the Life of his Captain & was severely wounded. His Activity had made him so remarkable That I personally interfered with The Baron Steuben at the Surrender of York Town to obtain that He might not risk the Hazard of being sent Prisoner into the Country—& had I been with The Regiment when it was disbanded, I should have felt it my Duty to have recommended him as a proper Object for his Majesty’s Bounty of Chelsea, not having that Power, I humbly hope that you will direct him to be examined; in particular, as being a Loyal Negro, He has no other means of reaping the Protection his Services in The Opinion of Every Officer of the Corps as well as mine most amply merit.

I have the honor to be Sir, your most obt.

& most Humble St.

J G Simcoe

Lt. Coll. Comdt. (late) Q Rangers[22]

By Simcoe’s statement above, this young man had clearly joined the Rangers at the Siege of Charleston, which coincides nicely with his correspondence with André and certificate from the previous month. But was “B E Griffiths” actually Barney? Simcoe himself provided the answer, by writing both this certificate and his book, A Journal of the Operations of a Partizan Corps called the Queen’s Rangers, in which he described in detail the terrific fighting that took place on June 26, 1781 at the Battle of Spencer’s Ordinary, Virginia. If the actions mentioned in Simcoe’s letter to the War Office were indeed that conspicuous, the accounts should likewise be in his published account of the battle. And they were.

While Simcoe’s narrative of the battle is quite lengthy, as the bloody action that day was quite complicated, it is necessary here to only cover the relevant passages. At this point in the war, the Queen’s Rangers were a part of the army serving under Lieutenant General Lord Cornwallis, which was just then occupying Williamsburg, Virginia. The Queen’s Rangers, along with a small number of New York Volunteers, North Carolinians, and Hessian Jägers, had lagged behind the main army to collect some cattle, giving the main Continental force in Virginia under Maj. Gen. the Marquis de Lafayette an opportunity to attack:

The highland Company of the Queen’s Rangers had been posted in the wood, by the side of the road, as a piquet: a shot or two from their sentinels gave an alarm, and Lt. Col. Simcoe gallopping across the field, towards the wood, saw Capt. Shank in pursuit of the enemy’s cavalry. They had passed through the fences which had been pulled down, as before-mentioned, so that, unperceived by the Highlanders, they arrived at Lee’s farm, in pursuit of the people who were collecting the cattle. Trumpeter Barney, who had been stationed as a vidette, gave the alarm, and gallopped off so as not to lead the enemy directly to where the cavalry were collecting their forage and watering, and, with great address, got to them unperceived by the enemy, calling out “draw your swords Rangers, the rebels are coming.” Capt. Shank, who was at Lee’s farm waiting the return of the troops with their forage, in order to post them, immediately joined, and led them to the charge on the enemy’s flank, which was somewhat exposed, while some of them were engaged in securing the bat-horses at the back of Lee’s farm: he broke them entirely. Serjeant Wright dashed Major Macpherson, who commanded them, from his horse, but, leaving him in pursuit of others, that officer crept into a swamp, lay there unperceived during the action, and when it was over got off. Trumpeter Barney dismounted and took a French officer, who commanded one of the divisions. The enemy’s cavalry were so totally scattered, that they appeared no more: many of them were dismounted, and the whole would have been taken, had not a heavy fire out of the wood, from whence the Highland company were now driven, protected them . . . Cornet Jones, who led the first division of cavalry, was unfortunately killed: he was an active, sensible, promising officer. The mounted riflemen of the Queen’s Rangers charged with Capt. Shank: the gallant Sergeant M’Pherson, who led them, was mortally wounded. Two of the men of this detachment were carried away by their impetuosity so far as to pass beyond the enemy, and their horses were killed: they, however, secreted themselves in the wood under some fallen logs, and, when the enemy fled from that spot, they returned in safety to the corps. By a mistake, scarcely avoidable in the tumult of action, Capt. Shank was not supported, as was intended, by the whole of his cavalry, by which fewer prisoners were taken than might have been: that valuable officer was in the most imminent danger, in fighting his way back through the enemy, who fired upon him, and wounded the Trumpeter Barney and killed some of the huzzars, who attended him.[23]

Without doubt, the person that Simcoe had recommended to the War Office, B E Griffiths, was the same “Trumpeter Barney” described in Simcoe’s Journal. Denied an opportunity to serve as a full-fledged trooper, the young liberated slave capitalized on what opportunity he had by enabling his troop to escape a situation where they were not in a proper fighting posture, capturing an enemy cavalry officer of the 1st Light Dragoons,[24] and saving the life of his troop’s commander, Capt. David Shank.[25]

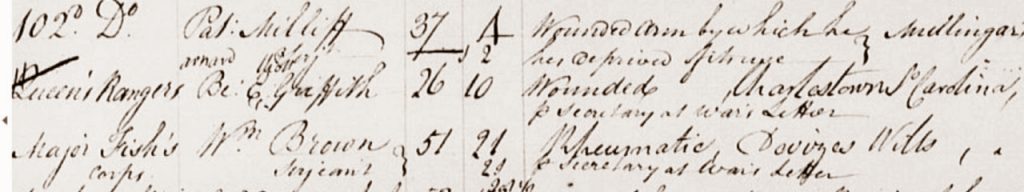

Did Trumpeter Barney get his pension? Yes indeed. The Chelsea Admission Book for August 5, 1789 records one Barnard E. Griffiths (listed in an earlier entry as “a negro”) admitted to Chelsea on the recommendation of a letter from the Secretary at War. It further added that Griffiths was twenty-six years old in 1789, was a laborer from Charleston, South Carolina, and had been wounded. The one incorrect detail listed, not uncommon in the Chelsea records, was years of service, given as ten.[26] This may have stemmed from the fact that Barney had actually accompanied Simcoe back to England in November 1781 on board the Swallow packet and had never officially received a discharge, although he no doubt stopped receiving pay when the corps was disbanded on October 10, 1783.[27]

While a number of blacks served as drummers, fifers, trumpeters and pioneers in different Provincial units, no other received the sort of commendation written by their commanding officer as Barney did from Simcoe. What other acts of heroism may have taken place, but were not been passed down to us in the annals of history?

[1]“Numbers of Men Admitted Out Pensioners of Chelsea Hospital” for the years 1778, 1779, 1780, 1781, 1782, 1783 and 1784. War Office, Class 245, Volume 2, Great Britain, The National Archives (TNA).

[2]Rogers’ warrant from Howe to raise the Queen’s Rangers is undated, but appears to be from about August 1, 1776. Simcoe Family Papers, F 47-3-1-1, Correspondence 1768-1776, Archives of Ontario.

[3]Petition of Robert Cook to the Commissioners for American Claims, Saint John, New Brunswick, March 17, 1786. Audit Office, Class 13, Volume 21, folios 120-121, TNA.

[4]“Inspectors Report to the Adjutant General 14th March 1777.” Headquarters Papers of the British Army in America, PRO 30/55/441, TNA.

[5]Regimental Orders for the Queen’s Rangers, March 30, 1777. Colonial Office, Class 5, Volume 98, page 87, TNA.

[6]Deserter interview of William Fennell, March 2, 1777. George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence, 1697-1799, MSS 44693, Reel 040, Library of Congress.

[7]Sir Henry Clinton to Lord George Germain, New York, November 8, 1781. Simcoe Papers, 1774-1824, University of Michigan, William L. Clements Library (CL).

[8]Orders by Adjutant General Francis Lord Rawdon, New York, July 20, 1778. Simcoe Papers, CL.

[9]The initial expedition to take Charleston sailed from New York in late December 1779. The Queen’s Rangers had been left behind on Staten Island primarily because Simcoe was a prisoner at the time, having been taken on the raid on Somerset Court House, New Jersey, October 26, 1779. He returned to the British in January 1780 and immediately solicited to have the corps join the troops to the southward. The Queen’s Rangers were one of five battalions sent as a reinforcement on April 1, 1780. Simcoe to Deputy Adjutant General John André, New York, February 23, 1780. Sir Henry Clinton Papers, Volume 86, item 26, CL.

[10]Simcoe to André, no date, c–May 1780. Sir Henry Clinton Papers, Volume 95, item 57, CL.

[11]Simcoe to André, no date, c–May 1780. Sir Henry Clinton Papers, Volume 95, item 56., CL.

[12]Simcoe to André, no date, c–May 1780. Sir Henry Clinton Papers, Volume 95, item 58, CL.

[13]Muster Roll of Captain John Saunders’ Company, June 24 to August 24, 1780. RG 8, “C” Series, Volume 1863, page 35, Library and Archives Canada. Hereafter cited as LAC.

[14]Muster Roll of Capt. Robert McCrea’s Company, June 24 to August 24, 1780. RG 8, “C” Series, Volume 1863, page 39, LAC.

[15]Muster Roll of Capt. James Kerr’s Company, June 25 to August 24, 1780. RG 8, “C” Series, Volume 1863, page 32, LAC.

[16]Muster Roll of Capt. Stair Agnew’s Company, June 24 to August 24, 1780. RG 8, “C’ Series, Volume 1863, page 31, LAC.

[17]Muster Roll of Capt. John Mackay’s Company, August 24, 1780. RG 8, “C’ Series, Volume 1863, page 42, LAC.

[18]“Certificate of Col. Simcoe dated 25th Feby. 1789.” Audit Office, Class 13, Volume 5, folio 30, TNA.

[19]Muster Roll of Capt. David Shank’s Troop, Camp near Newtown, September 2, 1783. War Office, Class 12, Volume 11035, TNA.

[20]Queen’s Rangers Abstract of Pay, April 25 to June 24, 1781. RG 8, “C” Series, Volume 1864, page 17, LAC.

[21]“Establishment of the Queen’s Rangers Commanded by Lieut. Colonel Simcoe, consisting of Five Troops of Dragoons, and Eleven Companies of Foot, from 25th December 1782 inclusive.” Headquarters Papers of the British Army in America, PRO 30/55/6547, TNA.

[22]Simcoe to Secretary at War George Yonge, March 20, 1789. War Office, Class 121, Volume 6, No. 420, TNA.

[23]John Graves Simcoe, Simcoe’s Military Journal: Journal of the Operations of a Partizan Corps called the Queen’s Rangers (New York: Bartlett and Welford, 1844), 226-237.

[24]According to Heitman, a cavalry officer named “Lieutenant Bresco” was captured at Spencer’s Ordinary. The 1st Light Dragoons under Major Call were the cavalry in the battle for Lafayette. “Return of the killed, wounded, and missing of the Light Corps under Col. Butler in the action of the 26th June 1781,” Papers of the Continental Congress, M247, reel 176, i156, page 169, National Archives and Records Administration. Thank you to Dr. Robert Selig for this reference. See also Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army during the War of the Revolution (Washington, DC: Rare Book Shop Publishing, 1914), 118.

[25]Trumpeter “Black Barney” was listed on the muster roll of Capt. David Shank’s Troop of the Queen’s Rangers at the time of the battle. RG 8, “C’ Series, Volume 1864, page 21, LAC.

[26]Chelsea Admission Book entry for August 5, 1789. War Office, Class 116, Volume 9, TNA.

[27]Diary of Frederick Mackenzie (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1930), 2: 694. Thanks to Lt. Col. Don Londahl-Smidt, USAF (ret) for this reference.

3 Comments

Outstanding article. Well done!

I am interested to learn if Simcoe and John Butler, of Butler’s Rangers, shared their experiences with each other since Simcoe and his wife lived in Niagara for a time prior to Butler’s death in 1796?

Hello Donald. While I do not know the answer to your question, you might consider delving into Simcoe’s Papers in the Archives of Ontario to see if there is any correspondence to or from Butler in there. It would be fun to discover they did. http://ao.minisisinc.com/scripts/mwimain.dll/144/ARCH_DESC_FACT/FACTSDESC/REFD%2BF%2B47?SESSIONSEARCH