The Continental Navy. Words that didn’t exactly strike fear into the heart of the mighty British Royal Navy. For most Americans, knowledge of the early American Navy likely begins and ends with the daring exploits of John Paul Jones, starting in 1778. Indeed, it was not the Continental Navy, but the French Navy, that was decisive in defeating the British at Yorktown. But why were the French there? Conventional wisdom identifies the American victory at Saratoga in 1777 as a major reason. While it may have been the triggering event, sealing French aid for the American rebels was not a one-event story; it was a process involving diplomatic as well as military maneuvers.

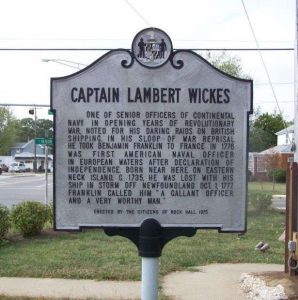

Historians debate the contribution of the Continental Navy to the success of the Revolution and France’s entrance into the conflict. Some, acknowledging that naval actions were instrumental to the outcome, dismiss the notion that the Continental Navy had much impact at all, contending it was the mighty Royal Navy and the French Navy that determined outcomes. In terms of size, the Continental Navy acquired nearly sixty ships over the course of the war, but there were fewer than forty owned in any one year and many fewer in service.[1] The Continental Navy, even before Jones had yet begun to fight there, played a pivotal role in this process through their activities in the European theater in 1776 and 1777. And while many people were involved in this effort, this story is focused on one. His name was Capt. Lambert Wickes.

The Continental Navy had no pretensions about confronting the British Navy head on. This would have been suicide. It did play two overlapping roles. First, to keep the Continental Army supplied, covering for shortfalls in American manufacturing capacity. Much of this work was with the illicit cooperation of the French. Second, to stoke further conflict between the British and French by preying on British shipping from the shelter of French ports. What ensued was a kind of brinksmanship, as the Americans continually pushed the two countries close to war and then backed off. American success in the effort is an interesting study which could be called “Gunboat Diplomacy, Revolution Style.” The activities of Wickes and his naval brethren were critical in positioning the French to eventually ally with America in the Revolution.

Unfortunately, Wickes would not be around to see the fruits of his labors. His ship, the Reprisal, on its return trip to America, was wrecked in early October 1777, swamped by a Nor’easter off Newfoundland which killed all aboard except the cook. Jonathan Williams, Benjamin Franklin’s grandnephew,writing to the American Commissioners in France late in 1777, reported, “I have just heard a melancholy Accot of Capt Wickes having foundered on the Banks of Newfdland. This I am much disposed to disbelieve, and the more so as I think the accot does not carry with it an air of certainty . . . a man arrived in a french Vessell from the Banks who called himself the Steward of the Reprisal, and said that when the Ship foundered he saved himself by the gang Ladder which supported him, ‘till french Vessell took him.”[2] Alas, Williams’ report was true, and the life of one of the most successful and notorious of the Continental Navy’s captains came to a premature end that early October day. But Wickes left a remarkable list of accomplishments that have been overshadowed by the later adventures of Jones.

Born in 1735, Maryland native Wickes took a visible role early in the rebellion. He first caught the attention of Rebel leaders when, despite British pressure, he refused to carry British tea into Baltimore on his merchant ship the Neptune. Two weeks earlier, one ship that did carry British Tea to Annapolis, the Peggy Stewart, was burned by Rebels in the less-celebrated “Annapolis Tea Party.”

This notoriety secured Wickes an appointment to the new Continental Navy, where he was listed eleventh in seniority among the original twenty-four ranked commanders and captains (Jones was eighteenth). He was assigned to the Reprisal, a vessel purchased for the Navy by the Continental Congress. The schooner was about 200 tons, one hundred feet long and thirty feet wide. It carried eighteen 6-pounder carriage guns and was served by a crew of 130 seamen.[3] Wickes’ first engagement became known as the Battle of Turtle Gut Outlet. An American ship, the Nancy, returning from the Caribbean with a much-needed supply of nearly 400 barrels of gunpowder, as well as other military supplies, ran aground in the Capes of Delaware. In this vulnerable position, it came under attack by HMS Kingfisher. Wickes and the Reprisal, along with John Barry and the Lexington, held off the British ship long enough for the crew to off-load about half the gunpowder and other items. As the British closed, a trail of gunpowder was set as a fuse, which detonated the remaining gunpowder as the British boarded the Nancy, destroying both ships and killing several British sailors.[4] Unfortunately, Richard Wickes, Lambert’s brother and 3rd lieutenant, was also killed by a cannonball near the end of the fight. “We have this Consolation,” Lambert Wickes wrote his elder brother Samuel, “that he fought like a brave Man & was fore most in every Transaction of that Day.”[5]

Next for Wickes was an important mission covered in an earlier article in this Journal.[6] He was assigned to transport Continental Congress envoy William Bingham, who working with the French would help obtain supplies for the American war effort from his post in Martinique. They set out on July 3, 1776, and upon arrival encountered HMS Shark in the harbor. After shuttling Bingham safely to shore, Wickes engaged the Shark, a conflict that was eventually broken up by the firing of French shore batteries, causing the Shark to withdraw. This was the first of many instances where Wickes would provoke conflict between the two superpowers, causing British protests and sometimes testing French tolerance, anxious though they were to avenge losses from the Seven Years’ War, but nominally neutral in the American rebellion.

En route to Martinique, armed with privateering commissions backed by the firepower of the Reprisal, Wickes had started privateering by nabbing three British merchant ships, carrying mostly commercial goods (rum, cocoa, etc.). The ships and goods were returned to the United States for sale, escorted by a large portion of his crew. He also captured a fourth ship, this one the Duchess of Leinster, headed for Ireland. Reluctant to retain this prize, due to his shortage of (trusted) crew, Wickes sent the ship its way. But instead of divulging the true reason for their release, he told their captain he was letting them go because they were Irish property and the United States was not at war with Ireland. His hope was that this information would get back to Ireland, which it appears to have done. A bit of positive public relations never hurts, even for a privateer!

Wickes received a hero’s welcome upon his return to Philadelphia, as well as kudos from the Secret Committee of Correspondence of the Continental Congress on September 21, 1776, which wrote that “Capt Wickes’s behaviour meets the approbation of his Country & Fortune seems to have had an Eye to his Merit when She Conducted his three prizes safely in.”[7]

Wickes’ next human cargo would be even more valuable. His heroism earned him the assignment of carrying the venerable Benjamin Franklin (along with two of his grandsons) to France to be the American Commissioner. An October 24, 1776 letter from the Committee of Secret Correspondence to the current commissioners in France states,

The Congress having Committed to our charge and Management their Ship-of-War Called the Reprisal commanded by Lambert Wickes Esq. . . . we have allotted her to carry Doctor Franklin to France and directed Captain Wickes to proceed to the Port of Nantes where the Doctor will land and from thence proceed to Paris, and he will either Carry with him or Send forward this letter by express as to him may then appear best. The Reprisalis a fast Sailing Ship and Capt Wickes has already done honor in Action to the American Flagg.[8]

On the same day, the Continental Marine Committee of Congress informed Wickes of his heretofore secret cargo:

The Honourable Congress having thought proper to Submit the Ship Reprisal under your command to our direction for the present voyage or Cruize. You are to be governed by the following orders. The Honble Docter Franklin being appointed by Congress one of their Commissioners for negotiating some publick business at the court of France. You are to receive him and his Suite on board the Reprisalas passengers whom it is your duty and we dare Say it will be your inclination to treat with the greatest respect and Attention and your best endeavours will not be wanting to make their time onboard the Ship perfectly agreeable.[9]

While the instructions were straightforward about the need to deliver Franklin with all due haste, they provided Wickes leeway to take some prizes, if Franklin approved. The opportunity arose near the end of the voyage, and on November 27, 1776, the Reprisal captured two British merchant ships, the Vine and the George, both of which would later be sold upon arrival in Nantes, France. With this, Wickes became the first Continental Navy captain to capture prizes in European waters. The Reprisal approached the coast of France in November, but contrary winds prevented it from reaching Nantes. An impatient Franklin disembarked December 3 to complete the rest of the trip by land.

Thus began the delicate dance of selling American-captured British prizes, operating out of French harbors, as France strived to maintain its neutrality. In his writings, Wickes was quite clear that his orders were to continue patrolling and capturing British prizes. Wrote Wickes: “those orders [to depart] from the French Ministry I look on as Fenness [finesse] and only given to Save appearances and gain time, as they are not yet quite ready for a Warr.”[10] He was correct, the French weren’t ready; as well as needing some evidence that the American cause was winnable, they also were stalling for time to get their navy built up to a level where it could at least be competitive with the British. In the meantime, they would alternately ignore, disclaim knowledge of, explain away, or indignantly condemn (but without much action to back it up) American privateering activities out of their ports.

Wickes for his part was all in, and over the first half of 1777 conducted two voyages circumnavigating Ireland, the first with the Reprisal alone, the second a three-boat squadron of Continental Navy vessels. Collectively, these two voyages seized twenty-three ships, pursued many more, slowed or halted much commercial shipping in the region, and generally terrorized coastal areas. Reported Williams:

The little american Squadron under Commodore Wickes have made very considerable havoc on the Enemys Vessells in the Irish Channel, this has created universal Terror in all the Seaports throughout Ireland and on that side of England and Scotland. In some places they muster’d their militia in apprehension of a Descent, and their fears have taught them to respect our naval Force.[11]

However, not all ships seized were to be sold. Of the twenty-three captured, seven were sunk and two belonging to smugglers were released.[12] When seized ships were taken to France, they had to be sold, but the problem arose of what to do with the British prisoners. Having gathered about seventy-seven prisoners during the first cruise, Wickes made port at Port Louis, near L’Orient, France, arriving February 13, 1776. Once ashore, he paroled five British captains with the understanding they would not leave Port Louis or contact England. The latter promise was broken by Captain Charles Newman, who sent a letter to Britain’s Lord Stormont “to inform you of the taking the Swallow Packet, (lately under my Command) by the Reprisal an Arm’d Ship belonging to the American Congress.”[13]

Wickes’ first inclination was to trade the prisoners for American captives held in England. To that end he had Franklin write to Stormont inquiring

whether an Exchange may be made with him for an equal’ Number of American Seamen now Prisoners in England? We take the Liberty of proposing this Matter to your Lordship & of requesting your opinion . . . whether such an exchange will probably be agreed to by your Court. If your People cannot be soon exchanged here, they will be sent to America.[14]

To complicate this negotiation, and reacting to British outrage, the French gave Wickes twenty-four hours to depart L’Orient, rendering an exchange impracticable time-wise. Another of the paroled prisoners, John Hunter, wrote Stormont that

The reason that induced Capt Newman to be so precipitate in demanding The prisoners without waiting for Your Excellencys instructions, was a Report that was circulated in L’Orient, & supposed to be pretty well founded that Wickes had received orders to quit the Port in 24 hours—Had this been the case, there was no other expedient left to save 77 British subjects from being carried to America, & possibly prevailed on to serve against their Country.[15]

Wickes cannily evaded the twenty-four hour deadline by claiming that the Reprisal had leaks, was not seaworthy, and needed to remain in port for repair. To make sure the case was convincing, he had carpenters sign a second opinion certificate that “they thought The Ship Would be in Emminent Danger If Sent to See Without Carreanig and Repairing.” Wickes, to support these opinions, allegedly had “pumped water into the hold to simulate a leak.”[16] I will spare the reader the twists and turns of the ensuing diplomacy, where the passive-aggressive French Foreign Minister Vergennes vacillated between denying that any prize sales took place or that Wickes was even still in France, to decrying the situation and promising to take immediate action. The result was that the prizes were sold (for 90,000 livres)[17] and the prisoners released (seventy-two of whom returned to Britain while five elected to join Wickes’ crew).[18]

The second cruise around Ireland accounted for eighteen of the twenty-three ships captured, a high number facilitated by the fact the Wickes was commanding a three-ship convoy. He was joined by the sixteen-gun, 110-man Lexington, commanded by Henry Johnson, and the Dolphin, under Samuel Nicholson, with ten guns and 64 men. This cruise was also mired in controversy, which began even before its May 28, 1777 departure. Initially, Wickes’ crew refused to go, not having been paid prize money since the start of the voyage. Wickes made promises to mollify them for the time being “with much threats and a promise that the prize Money should be paid before they left Nantz, have prevailed on them to go to Nantz, but do not expect to get them from there till they are paid.”[19]

Once underway, success came fast. Nicholson wrote to the American Commissioners, “Just before taken A Snow Under the Lizard, bound for Falmouth, from Giberalter, loaded with Cork, we sent 8 prizes forward for the first Port they cou’d make in France or Spain, 7 we Sunk 1 we gave the Prisoners & 2 Smuggelers we gave their Vessells again, 3 Briggs loaded with Coals we Sunk in Sight of Dublin harbor.”[20] Heading back to L’Orient with their haul, they spotted one more ship to go after, but this intended prize was discovered to be British warship HMS Burford, a ship of the line and well above the weight class of any of the American vessels. Time for a full retreat. As Wickes described it, “Saw a large Ship of War off Ushant, Stood for her at 10 A M discovered her to be a large Ship of War standing for us, 3 Bore away and made Sail from her, She Chased us till 9 P M, and Continued fireing at us from 4 till 8 at Night, she was Almost within Musquet Shott.”[21]

To escape, Wickes got creative. To lighten the Reprisal, he “ordered her Guns to be Thrown over Board and four Beams sawed out which orders were executed accordingly and the said Privateer was carried into the Port of Saint Maloes [St. Malo] in the said Kingdom of France under the directions of a French Pilot.”[22] Wickes was ecstatic, stating to Johnson that “our late Cruize has made a great deal of Noise & will Probably Soon bring on a Warr between France and England which is my Sincere Wish.”[23]

The American convoy was safely back in port, but this being a French port, the diplomatic sparks again flew, reducing the furor following their last foray to a minor spat in comparison. What angered the British even more was an additional set of prizes taken by another American privateer, Gustavus Conyngham, operating his ship, the Revenge, out of Dunkirk, on questionable authority (the orders of American Commissioner Silas Deane had been verbally countermanded).[24] Privateering efforts from Dunkirk were strictly forbidden, even under the shaky British-French neutrality. The fact that Conyngham operated with a predominately native French crew drove the final nail for the British. Vergennes, perhaps with a wink, excoriated the American actions in a letter to Franklin and Deane:

After such repeated warnings, the motives of which have been explained to you, we had no reason to expect, Gentlemen, that the said Wickes would continue Cruising in European Waters, and we could only be greatly Surprised that, having joined the privateers the Lexington and the Dolphin in order to harass the English coast, they should, all three, then come in to take refuge in our Ports.[25]

In response to British protests, King Louis XVI ordered the American warships detained in port, and all captains to sign paroles agreeing not to leave France without permission. This was inadequate to satisfy the British, and the crisis came to a head when Lord North sent a special envoy to France to threaten war if the situation were not rectified to Britain’s satisfaction. Vergennes and the American Commissioners were shocked when, after the French had thrown the American purchaser of the Revenge in the Bastille for the Dunkirk escapade, the only additional action needed to defuse the situation was for France to dismiss the two American ships, the Reprisal and the Lexington, from all French ports.[26]

The immediate threat of war between Britain and France blew over for now. The American ships were sent off to meet their fates, with the Lexington captured by the British cutter HMS Alert just two days out of port, and the Reprisal, as noted previously,meeting its demise off the coast of Newfoundland. Conyngham, for his part, was eventually arrested by the French in Dunkirk and due to be extradited to Britain before Franklin negotiated his release.[27]

Was Lambert Wickes a diplomat, Naval Officer, privateer, or pirate? Along this continuum of roles, some distinctions are clear, others are a bit blurry. Clearly because of the battle action he saw, Wickes was not merely a diplomat. Said one naval historian, “to call him a diplomat is a little too high praise, except in the sense that every naval officer who conducts himself with credit in ticklish diplomatic situations is a diplomat”[28] Yet, his actions drove, and were specifically intended to drive, diplomatic outcomes. Hence one biography is titled Lambert Wickes, Sea Raider and Diplomat.[29]

On the other end of the scale, it would be difficult to classify him as a pirate, though it’s not much of a stretch to think that the terrorized people living along the British and Irish coasts regarded him as such. His operations appear to have been largely self-funding, and he likely did not make the substantial personal profits that might be associated with a pirate.

Beyond this, distinctions are less clear. Some have called privateering nothing but legalized piracy, but many scholars have disputed the conflation of the two terms; privateers engage in warfare which nations authorize and consider legitimate, while pirates are international outlaws.[30] As an officer of the Continental Navy, Wickes initiated attacks that were military in nature, and performed them using a ship owned by the US government. This would place them in the category of naval warfare with a declared enemy. His targets, however, were commercial rather than naval vessels, and were sold as privateering prizes.

Most of the material I have read regard Wickes as a privateer, and I think that title fits, though later officers in this theater (e.g. John Paul Jones) would chafe at this label. Jones denounced privateers, stating, “Publick Virtue is not the Characteristick of the concerned in privateers,” calling them “licensed robbers.”[31] Critics of privateers question the morality of their behavior, their sapping of human resources available to the Continental Navy, private profitability versus patriotic motives, and one of Jones’s major peeves, their failure to use their prisoners to trade for American captives. On the other hand, supporters regard privateers as brave and patriotic, their warfare legitimate based on prevailing international norms, and were practical in that they represented a major tactic for an outmanned America against the mighty Royal Navy.

Regardless of how you classify him, Wickes had an almost unrivalled record of success in serving the American cause. Historian Steven Howarth in his book, To Shining Sea: A History of The United States Navy, states,

Had [Wickes] lived, he might well have outshone his more celebrated colleague John Paul Jones; and of the two, it could be argued that Wickes was the more courageous, for when he conducted his pioneering raids, he (unlike Jones), had no guaranteed safe port in France. Wickes paved the way for Jones. Today Jones is far more widely remembered, and in the context of the U.S. Navy’s whole history, that is right. . . . But at the time, Wickes’s contribution to the immediate cause of American independence was far greater.[32]

One can only speculate what Wickes and Jones might have done together, but that was not to be, and Jones’s stature is altogether appropriate. Wickes’ impact and that of the Continental Navy during his time are certainly underappreciated. He was instrumental in nudging (and sometimes shoving) France closer to its eventual alliance with America.

The Wickes name has lived on in the Navy’s memory. Two destroyers named for Wickes were commissioned, one each in World War I and World War II. Each was christened by a Wickes descendent.[33]

[1]Overview of the Continental Navy, Oxford Reference, www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095634985?rskey=G3kiyt&result=3, accessed October 16, 2018.

[2]Jonathan Williams, Jr. to the American Commissioners in France, November 29, 1777, in Naval Documents of the American Revolution, Michael J. Crawford, et al. ed. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1962 – ), 10: 1050-1051 (NDAR).

[3]Gordon Bowen-Hassel and Dennis Michael Conrad, Sea Raiders of the American Revolution: The Continental Navy in European Waters (University Press of the Pacific, 2004), 1.

[4]Pennsylvania Ledger, Saturday, July 6, 1776, NDAR, 5: 952.

[5]Lambert Wickes to Samuel Wickes, July 2, 1776, NDAR, 5: 883.

[6]Richard J. Werther, “William Bingham, Forgotten Supplier of the American Revolution,” Journal of the American Revolution, June 7, 2017.

[7]Committee of Secret Correspondence of the Continental Congress to William Bingham, September 21, 1776, NDAR 6: 937.

[8]Committee of Secret Correspondence to the American Commissioners in France, October 24, 1776, NDAR, 6: 1,405.

[9]Continental Marine Committee to Captain Lambert Wickes, October 24, 1776, NDAR, 6: 1,400-01.

[10]Lambert Wickes to the Committee of Secret Correspondence, February 28, 1777, NDAR, 8: 624.

[11]Jonathan Williams to Committee of Foreign Affairs, Nantes, Aug 10, 1977, NDAR, 9: 561.

[12]News from Whitehaven, June 26, 1777, NDAR, 9: 429.

[13]Charles Newman to Lord Stormont, February 21, 1777, NDAR, 8: 602.

[14]American Commissioners in France to Lord Stormont, February 23, 1777, NDAR, 8: 605.

[15]John Hunter to Lord Stormont, February 23, 1777, NDAR, 8: 606-7.

[16]Lambert Wickes to Benjamin Franklin, February 28, 1777, Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-23-02-0257.

[17]August Caron de Beaumarchais to Comte de Vergennes, March 7, 1777, NDAR, 8: 650. Beaumarchais, who played a prominent role in the French arms trade with the Americans, bemoaned having arrived in L’Orient after the sale took place, claiming he could have gotten 600,000 livres. This was the sacrifice made to expedite the sale.

[18]Extract of a Letter from France, March 10, 1777, NDAR, 8: 660.

[19]Lambert Wickes to the American Commissioners, L’Orient April 27th. 1777,Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-23-02-0424.

[20]Samuel Nicholson to American Commissioners in France, St. Malo, June 28, 1777, NDAR, 9: 442.

[21]Lambert Wickes to the American Commissioners in France, June 28, 1777, NDAR, 9: 440.

[22]Deposition of William Newell, James Newell, and John Harrison, July 25, 1771, NDAR, 9: 528.

[23]Lambert Wickes to Captain Henry Johnson, July 20, 1777, NDAR, 9: 515.

[24]Jonathan Dull, A Diplomatic History of the American Revolution (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1985), 83.

[25]Vergennes to Franklin and Deane, July 16, 1777, NDAR, 9: 501-502.

[26]Dull, A Diplomatic History, 85. The third ship, the Dolphin, was re-fitted and retained for use by the American Commissioners.

[27]Louis Arthur Norton, “Captain Gustavus Conynham: America’s Successful Naval Captain or Accidental Pirate?,” Journal of the American Revolution, April 15, 2015.

[28]Louis H. Bolander, “Review of Lambert Wickes, Sea Raider and Diplomat: The Story of a Naval Captain of the Revolution,”The American Historical Review, Vol 38, No. 1 (October 1932), 129.

[29]William Bell Clark, Lambert Wickes, Sea Raider and Diplomat: The Story of a Naval Captain of the Revolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1932).

[30]Michael Crawford, “The Privateering Debate in Revolutionary America,” The Northern Mariner, XXI No.3 (July 2011), 222.

[31]John Paul Jones to Robert Morris, December 11, 1777. NDAR, 10: 1091-93. This letter, a rant on several issues, trails off at the end, unsigned.

[32]Steven Howarth, To Shining Sea, a History of the United States Navy: 1775-1998 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999), 31.

[33]Naval History and Heritage Command, www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/w/wickes-ii.html, accessed October 16, 2018. Lambert Wickes never married nor had children, thus the descendants were those of one of his six Wickes siblings.

9 Comments

I had never heard of Cpt. Wickes until this brilliant piece. Another minor character who played a huge role in the overall theater of the Revolution—hope to find a biography on the man. Well written, and I’m sure he would have made a great candidate for the previous article on Promising players in Early America.

This is a great article! Thanks.

I particularly appreciate the discussion of privateering vs. proper naval activity. The distinction was important on many levels, not the least of which was that privateers kept a larger share of their prize money than officers and crew of the United States Navy. The latter was constantly losing officers and crew to the business of privateering, even though naval officers were typically afforded more respect than officers aboard privateers!

The practice fell off for Britain and France during the 19th century and I believe they announced it was illegal in the Declaration of Paris after the Crimean War. Predictably, the United States refused to go along with the declaration; commissioning privateers was cheaper than building a Navy. If I recall correctly, the United States Government still has the authority to commission privateers today!

In any event, Wickes’ status would have remained murky for some time. Only governments could commission naval vessels and officers or issue Letters of Marque and, arguably from the British viewpoint, the Continental Congress didn’t qualify during Wickes’ period of active cruising. The threat of being hanged as a pirate was always present for U.S. naval officers.

I am curious about the discussion of privateering vs. legitimate naval activity myself, and maybe I’m getting hung up on one sentence that you gentlemen, Richard and Eric, could help me with. In the article you write, “As an officer of the Continental Navy, Wickes initiated attacks that were military in nature, and performed them using a ship owned by the US government. This would place them in the category of naval warfare with a declared enemy. His targets, however, were commercial rather than naval vessels, and were sold as privateering prizes.”

Is it the nature of the sale of the prizes that would particularly distinguish them as privateering prizes? During the Napoleonic Wars, for instance, Capt. Henry Digby of the British Navy took a large number of prizes, many of them commercial vessels belonging to France and Spain. As far as I am able to determine, they were considered legitimate naval prizes; I have read nothing about them being held up in prize court. Or is it simply the murky situation created by Wickes being a naval officer holding a privateering commission?

The distinction isn’t found in the choice of target (Digby’s prizes would have been legitimate in the scenario you describe), but in the nature of the authority to conduct the attack and the legal status of the ship and crew conducting it. Did they belong to a state’s navy or were they private enterprises that had been granted a letter of marque to conduct activities on the state’s behalf?

Another way to look at it would be to view privateers as mercenaries; private companies. Private funds had to be raised to acquire, equip, and crew a ship and they had to make enough money to justify the expense and risk. Congress liked them because it was broke and could barely afford a navy. The “mercenaries” only got paid if they were successful, and then out of the proceeds of their success.

In the 18th century, captains and crews were rewarded for taking prizes with the sale of the prize and the distribution of the proceeds among various parties, including the captain and the crew. In the United States, privateers received a larger share of the prize money than officers and crew in the United States navy.

Does that help?

PS: By “state,” I don’t mean states as in “Virginia” or “Rhode Island,” but “national government,” as in “United States,” or “United Kingdom.” Old IR habits die hard.

Hi Eric,

Some, I think… I understand that Congress didn’t have the money to fund a navy so giving a privateer the authority to confiscate prizes on behalf of the United States would have appeared to be a pretty nifty solution. And I understand that when a government (say, George III) gave a Letter of Marque to a privateer, that ship had the authority to take prizes on behalf of the government, but categorically different from the authority that a naval vessel had over prizes taken. Wickes was using a ship owned by the US government but selling his prizes as privateering prizes. And he did also hold privateering commissions…? He’s neither fish nor fowl nor good red beef. I guess that’s what confused me.

You nailed it. In theory, Wickes could not be both a U.S. naval officer captaining a U.S. naval ship and a privateer at the same time. Richard would have to explain the contradiction. I can only speculate without researching it, but would start with the date and timing of his cruise vs. the date and timing of Congress adopting laws regarding the Navy vs. the date and timing of issuing his letters of marque. Things were pretty murky early on with overlapping lines of authority among the colonies and Congress–which itself wasn’t recognized internationally as a government capable of either commissioning a navy or issuing letters of marque. So…

Without getting into the legal nicities and rules around privateering, which wasn’t the primary point of the article, I would agree with the contradiction you have noted above above, but say that it was left to stand that way as a matter of expediency. The Continental Navy and the British Navy were both navies only in the way that a Matchbox toy and a Ferrari are both cars. As a practical matter, the only way we could contend in the naval milieu was to be a navy that took prizes and disrupted commerce, though this may differ from the way a “navy”, strictly defined, operates. As described in the story, Wickes turned tail and ran when he encountered a powerful British naval vessel. Prize monies for the most part went to the effort of supplying the war back in America, with a small allocation to sustain further privateering missions. Wickes and his crew were paid not out of those hauls but by the U.S. government. As also mentioned in the article, Wickes at one point he had to deal with a near mutiny as his crew had not been paid since leaving America.

Hope that helps. I guess the bottom line is that in war you do what you have to do (plus, as Eric points out, lines of authority were pretty murky at that time, enabling us to take liberties with the rules). The difference between our navy and a real navy, with all due respect to the Continental Navy and the brave men like Wickes who were in it, is best highlighted by the fact that it ultimately took the French Navy to defeat the British.

I am researching a painting, possibly a portrait of Capt. Wickes.

Are there any known images of the Captain for comparison. I have searched

the internet and can not find any.