In June 1777, Henry Hamilton, the British lieutenant governor for Quebec and Superintendent for Indian Affairs at Detroit, held a council at Detroit with all who would attend. His goal was simple: mobilize the western Indian nations to attack Americans all along the Ohio frontier, just as the Six Nations were doing along the northern frontier in Pennsylvania and New York. In addition to the local militia and Frenchmen who called Detroit home, senior leaders from the Ottawa, Chippewa, Miami, Shawnee, Potawatomis, Delaware, and Huron/Wyandot nations all attended.[1] Many Indians took up Hamilton’s call. The lieutenant governor then issued a general proclamation, calling on all who read it to abandon the American cause, offering shelter to those who came within the control of British authorities, and enjoining those so inclined to take up arms against the rebel cause by promising two hundred acres of land as a bounty.[2] Together, the council and proclamation represented a change in British strategy north and west of the Ohio River, moving from a defensive crouch to a more aggressive stance. It had some effect, both on the Native Americans and whites living along the frontier. By September, Brig. Gen. Edward Hand, commanding at Fort Pitt, could report to Washington, “the western Indians are United against us. Gouvernor Hamilton’s Proclamation together with his Agents have gaind many of the Infatuated Inhabitants even of this remote Corner to the British Interest.”[3]

Congress formed a committee in the fall of 1777 to look into the state of affairs. On November 20, it took up the committee’s report, which accurately noted, “the Shawanese and Delaware Indians continue well affected and disposed to preserve the league of peace and amity entered into with us; for which reason they are threatened with an attack by their hostile neighbours who have invaded us, and are at the same time exposed to danger from the attempts of ill-disposed or ill-advised persons among ourselves.”[4] With that in mind, the committee recommended appointing three commissioners and dispatching them to Fort Pitt to: 1) further investigate the sources of the “spirit of disaffection” on the frontier and determine those steps needed to rectify the situation; 2) remove and replace any American officers for misconduct; 3) imprison those acting against the “rights and liberties of America” given sufficient evidence of misbehavior; 4) cultivate the friendship of the Shawnee and Delaware; 5) engage individuals of the Shawnee and Delaware tribes in American service; and 6) cooperate with the Continental commander, Gen. Edward Hand, to carry the war into territory controlled by the British, particularly Detroit. It also recommended that the legislatures of Virginia and Pennsylvania invest the commissioners with additional power over the local militia and citizens of their respective states to carry out the aforementioned mission. Congress adopted the report, with the additional provisos to prevail upon General Washington to send Col. William Crawford to Pittsburgh to assume command over the Continental and militia troops there and that the commissioners look into reports of misbehavior by Col. George Morgan, the Continental Indian agent at Pittsburgh.[5]

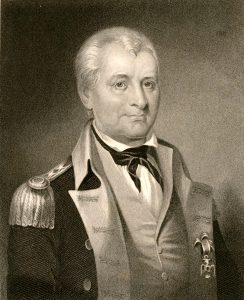

The Commissioners arrived with their plenipotentiary authorities in March 1778, just after the Continental commander, Brig. Gen. Edward Hand, aborted his foray against a rumored British supply depot on the Cuyahoga River, near where it emptied into Lake Erie. Hand’s campaign, known derisively as “The Squaw Campaign” for its desultory results, had likely set back the commissioners’ goal of building constructive relationships with the Shawnee and Delaware nations by killing and capturing members of the latter tribe. Hand never came close to the Cuyahoga, aborting his march without proceeding much beyond the Beaver River.

Almost simultaneous with the commission’s arrival, Pittsburgh erupted in a round of the disaffection that had helped prompt its visit in the first place. On March 25, Alexander McKee, Simon Girty, Matthew Elliott, and four other men slipped out of Pittsburgh bound for the Ohio country and, eventually, Detroit, where all would join the British cause. Girty, who had served the American militia and Continental Army as a messenger, scout, and interpreter on the frontier, only recently returned with Hand’s force. McKee was a former British Indian agent on parole. Elliott was a trader and close associate of McKee’s. All three were well-traveled, closely connected to Native American nations across the Iroquois Confederacy and the Ohio tribes, and had intimate knowledge of American military forces and capabilities from Kentucky County, Virginia to Lake Erie. Collectively, their defection represented a significant threat to American interests on the Ohio frontier.[6] John Heckewelder, a missionary from the Church of the United Brethren well-liked by various Delaware leaders, and some colleagues were then returning to their mission on the Muskingum River and described the state of affairs, “as we drew nearer to Pittsburg, the unfavourable account of the elopement of M’Kee, Elliot, Girty, and Others, from the latter place to the Indian country, for the purpose of instigating the Indians to murder, as was generally expected. Indeed the gloomy countenances of all men, women and children, that we passed, bespoke fear—nay, some families even spoke of leaving their farms and moving off.”[7] The missionaries routinely passed abandoned farms and houses on the journey.

The commissioners quickly reviewed Morgan’s case and reported, “after the clearest and most satisfactory testimonies, [we] wholly acquit the said Colonel George Morgan of the charges against him, of infidelity to his public trust, and disaffection to the American cause; and we testify that we are possessed of the knowledge of various facts and circumstances, evincing not only his attachment to that cause, but also an uncommon degree of diligence in discharging the duties of his employment, and of attention to the interests of the United States.”[8] While clearing their own Indian agent, who had good relations with the Delaware nation, might have given the Americans a firm foundation to pursue the diplomatic initiative, the McKee, Girty, and Elliott defection threatened to set it back. They made a beeline for the center of Delaware power on the Muskingum River.

On their flight from Pittsburgh, Girty, McKee, and Elliott spread stories that the Americans meant to exterminate the

whole Indian race, be they friends or foes, and possess themselves of their country; and that, at this time, while they were embodying themselves for the purpose they were preparing fine sounding speeches to deceive them, that they might with the more safety fall upon and murder them. That now was the time, and the only time, for all nations to rise, and turn out to a man against those intruders, and not even suffer them to cross the Ohio, but fall upon them where they should find them; which if not done without delay, their country would be lost to them forever![9]

McKee and Girty, at least, knew that story was exaggerated and that a major offensive from the Americans was not imminent that spring, which McKee reported to the British.[10]

The message exacerbated internal splits among the Delaware with a pro-peace faction led by Koquethaqechton, known as White Eyes, and anti-American clans led by Hopocan, known as Captain Pipe. Rather than let Captain Pipe use the exaggerations from McKee and others to stampede the tribe into war, White Eyes and his allies called for national council. There, he put the question of joining the war against the Americans on the table, but proposed delaying a decision ten days while the Delaware collected additional information, including a hoped-for message from the American Indian agent at Pittsburgh, George Morgan.[11] Captain Pipe agreed, but the chief also proposed to his clan that it declare any Delaware opposed to making war on the Americans as enemies of the people. One way or the other, he planned to bring the internal debate to an end and neutralize White Eyes once and for all. White Eyes responded by telling his own clansmen that if they were resolved to ignore his judgment and go to war, he would lead them and be the first to fall, rather than sending others to do his bidding, for he believed that war against the Americans would mean the end of the Delaware and he had no desire to outlive his nation.[12] Among the Delaware, the die was cast, or appeared so.

Back in Pittsburgh, George Morgan was already desperate to counteract McKee but getting word to the Delaware that the Americans wanted peace and a council meeting at Fort Pitt was proving difficult. Most of the scouts and messengers usually in the Pittsburgh area were already out on missions. Fortunately, Heckewelder and another missionary arrived about this time and resolved that the safety of the Delaware nation and, perhaps more importantly to the missionaries, the fates of their mission villages, depended on the continued neutrality of the Delaware.[13]

Heckewelder and a colleague promptly set out for the mission village of Gnadenhutten, traveling day and night while avoiding several war parties. After a few hours rest, Heckewelder proceeded to White Eyes’ village, where he received a cold welcome.[14] White Eyes pointedly asked Heckewelder several factual questions, suggesting he was counteracting some of the stories McKee had spread: were the Americans defeated everywhere east of the Alleghenies? Was Washington dead? Had Congress been dissolved and some of its members hanged? Were there but a few undefeated Americans now west of the Alleghenies intent on exterminating all Indians? Heckewelder assured him that the stories were false and asked if the Delaware would hold a council meeting at which he might address them. Tribal leaders agreed and Heckewelder delivered Morgan’s message, as well as a newspaper describing Burgoyne’s surrender. White Eyes took the opportunity to remind his fellow Delaware that the Americans had not attacked the Delaware and that the tribe had avoided the war’s destructive effects. For the moment, he had neutralized Hopocan’s efforts to drag the Delaware into the war on the British side.[15]

The commissioners had set April 25 as a deadline for responding to Morgan’s message, which made its way to the Delaware nation with Heckewelder and through correspondence with other missionaries residing in the mission villages along the Muskingum. White Eyes made a brief trip to consult with authorities at Fort Pitt, then returned to the Muskingum, satisfied that McKee had lied, but also understanding that the militia still looked askance at the Delaware.[16]

With Heckewelder’s delivery of his message and White Eyes’ visit to Pittsburgh, the Congressional Commissioners and George Morgan appeared to succeed in at least neutralizing Henry Hamilton and Alexander McKee’s efforts to enlist the Delaware nation by the early summer of 1778. The militia and military officers, however, still thought it necessary to carry the war into the Ohio territory, launching their own offensives against the Indians and Detroit. George Rogers Clark of Kentucky County, Virginia, was one of the first to act, proposing to Virginia Gov. Patrick Henry an expedition into the Illinois Territory. For his part, General Hand reported to Washington that the militia around Pittsburgh were of the same mind.[17] His own attempts at an offensive against Detroit in 1777 had been aborted due to insufficient supplies and manpower, followed by the similarly aborted “Squaw Campaign.”[18] In coming years, both Clark and Hand’s successors at Fort Pitt would return to the idea of an offensive against Detroit, which they erroneously thought the source of many of their problems. (The Native Americans in the Ohio region had their own reasons to wage war on the Americans, as they would do after the war.)

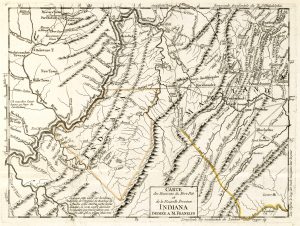

Morgan, Hand, and his successor, Brig. Gen. Lachlan McIntosh, realized that a direct campaign against Detroit would pass through Delaware country on the Muskingum. To sustain such an offensive in the spring of 1779, it would be necessary to build a series of forts capable of accumulating supplies. Such forts could also shield the Pittsburgh frontier from tribes raiding eastward and ease pressure against the Delaware from the warring tribes in western Ohio, namely the Wyandot.[19] Thus, they would satisfy several of the goals Congress had established when dispatching its commissioners to Pittsburgh. Preparations got underway, but logistical and political difficulties in 1778 created continual delays. Still, throughout the summer, McIntosh scrambled to assemble an army with which to campaign against Detroit.

With all that in mind, Morgan set out to reach a new agreement with the Delaware. The Ohio Indian nations met frontier whites at Fort Pitt annually, but their numbers had declined as an ever-growing number of western tribes joined the British. In September 1778, only the Delaware attended. Since militia were to make up a substantial portion of the American force, commissioners from Virginia and Pennsylvania were to be appointed. Gov. Patrick Henry appointed Andrew and Thomas Lewis, experienced soldiers and frontiersmen; Pennsylvania never got around to appointing its representatives. The Continental government was represented by George Morgan and Brigadier General McIntosh. Several officers from the 8th Pennsylvania and 13th Virginia Regiments were also present. The Delaware were principally represented by White Eyes, Gelelemend (known to whites as John Killbuck, Jr.), and Captain Pipe.[20] Discussions began on September 17. Eventually, White Eyes, John Killbuck, Jr., and Captain Pipe signed the Treaty of Fort Pitt on behalf of the Delaware. Andrew and Thomas Lewis signed the Treaty on behalf of the United States.

The Treaty, generally thought to be the first between an Indian nation and the new United States, contained six articles, beginning with a mutual pledge to forgive and forget past transgressions against one another and pledges of perpetual peace.[21] The treaty created a lopsided relationship, giving the Americans permission to pass through Delaware territory when conducting military operations against the British, requiring Delaware warriors to assist the Americans when possible, and establishing an asymmetrical economic relationship, the terms of which were to be left to Congress with the “advice and concurrence” of Delaware representatives. The United States also agreed to provide goods to the Delaware and to build and garrison a fort to provide for better security while the Delaware Nation’s warriors were away. It sought to replace revenge killings with trials when crimes were committed against either the Americans or the Delaware. The Americans guaranteed the integrity of Delaware territory, so long as the Delaware “shall abide by, and hold fast the chain of friendship now entered into.” Most interesting, and perhaps surprising, the contracting parties undertook “to invite any other tribes who have been friends to the interest of the United States, to join the present confederation, and to form a state whereof the Delaware nation shall be the head, and have representation in Congress.” In other words, the American commissioners, White Eyes, Killbuck, and Captain Pipe intended to create a fourteenth state populated by Indians and led by the Delaware! Such a development was subject to the approval of Congress, which never agreed to the treaty.

In the moment, the Treaty of Fort Pitt augured well for White Eyes and his attempts to maintain Delaware neutrality in the face of constant provocations from the western Indian nations allied with the British. On paper, it would guarantee Delaware independence from those tribes and held out the possibility of joining the United States as an equal, sovereign state on par with Virginia, Pennsylvania, New York, etc. Even more, Captain Pipe, the strongest advocate for war in the tribe, had signed it. Unfortunately, the paper signed at the negotiating table would not survive the harsh reality of the American Revolution on the frontier.

On September 26, at least some of the chiefs at Fort Pitt arrived back on the Muskingum. David Zeisberger, the Moravian missionary and diarist who lived close by with a growing number of Delaware who had embraced Christianity, recorded that the chiefs had “been informed” that they were now allies after first seeing a 900-man army poised to invade Indian territory, suggesting more of an intimidating affair.[22] This was the army McIntosh had been slowly assembling all summer for his campaign against Detroit, before the Treaty of Fort Pitt was signed. White Eyes, Killbuck, and Captain Pipe had a figurative gun pointed at their heads when they made their marks, even if the Treaty helped White Eyes achieve many of the goals he had for his nation. Subsequent historians argued that the Treaty had been misrepresented to the Delaware as securing their neutrality, rather than enlisting them in the American cause to facilitate McIntosh’s campaign. Killbuck later proclaimed the treaty he signed did not, in fact, say what he had been told it said: “I have now looked over the Articles of the Treaty again & find they are wrote down false.”[23] Morgan himself later proclaimed, “There never was a Conference with the Indians so improperly or villainously conducted.”[24] Liquor apparently flowed freely.

With the Treaty of Fort Pitt signed and the chiefs returned home to deliver the news, McIntosh finally launched a campaign against Detroit in October 1778. White Eyes joined him as a scout, suggesting he, at least, understood the new alliance between the Delaware and the United States, but he died on the march. His tribe was informed that smallpox took him, but Morgan believed he was assassinated.[25] Leadership fell to Killbuck and Captain Pipe, but others stepped up as well. Without White Eyes, however, Killbuck was not strong enough to keep the tribe from fragmenting and by the late spring of 1779, Captain Pipe had moved a large faction westward, from where he would wage war on the Americans. Killbuck eventually ended up sheltering under the less-than-secure walls of Fort Pitt, where he and members of his tribe were under as much threat from the locals as they were from warring western Indians. McIntosh got a little further than General Hand, eventually reaching the eastern tributary of the Muskingum, known today as the Tuscarawas River, where he built Fort Laurens. It was too far north to protect the Delaware and too far east to serve as a staging base against Detroit. After a failed siege by the western tribes in the first months of 1779, McIntosh’s replacement, Col. Daniel Brodhead abandoned the fort. Less than a year after it was signed, neither the Americans or the Delaware had much to show for the Treaty of Fort Pitt.

[1]“Council at Detroit, Official Report of Hamilton, June 17th, 1777,” in Reuben Gold Thwaites and Louise Phelps Kellogg, eds., Frontier Defense on the Upper Ohio, 1777-1778, Draper Series, Vol. III (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 1912), 7-13.

[2]“Hamilton’s Proclamation, Detroit, 24th June, 1777,” in Thwaites and Louise Phelps Kellogg, eds., Frontier Defense on the Upper Ohio, 1777-1778, Draper Series, Vol. III, 14.

[3]Edward Hand to George Washington, September 15, 1777, Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/?q=Ohio%20Period%3A%22Revolutionary%20War%22&s=1111311111&sa=&r=67&sr=, accessed November 13, 2018.

[4]Library of Congress, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, Volume IX, 1777, October 3-December 31 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1907), 943, memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=lljc&fileName=009/lljc009.db&recNum=7&itemLink=r%3Fammem%2Fhlaw%3A%40field%28DOCID%2B%40lit%28jc0092%29%29%230090008&linkText=1, accessed November 3, 2018.

[5]Ibid., 944. Loyalties were constantly changing on the frontier and it was common practice to accuse one’s personal, business, or political adversaries of disloyalty or misbehavior to advance an individual’s self-interest. In the eyes of many frontier settlers, Morgan’s greatest crime was to differentiate among Indian tribes and find sympathy with those earnestly seeking peace and justice. Crawford was a local landowner and long-time business associate of George Washington who had done extensive service with the Continental Army on the Atlantic seaboard.

[6]For excellent biographies of McKee and Girty, see Larry L. Nelson, A Man of Distinction among Them: Alexander McKee and the Ohio Country Frontier, 1754-1799 (Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 1999) and Phillip W. Hoffman, Simon Girty: Turncoat Hero (Franklin, TN: Flying Camp Press, 2008).

[7]Paul A.W. Wallace, ed., The Travels of John Heckewelder in Frontier America (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1958), 146. Wallace strung together entries from Heckewelder’s journals, letters, and diaries to create a continuous narrative.

[8]Library of Congress, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, Volume X, 1778, April 7, 1778 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1908), 313.

[9]John Heckewelder, A Narrative of the Mission of the United Brethren among the Delaware and Mohegan Indians, from its Commencement, in the Year 1740 to the Close of the Year 1808 (Philadelphia: McCarty & Davis, 1820), 170-171. Heckewelder was well known and well-liked by the peace factions among the Delaware, although he was still in Pennsylvania when Girty and company fled Pittsburgh. This is likely a summary of the main points McKee made, which Heckewelder would have been told second-hand not long after the event. That said, he had a clear dislike for Girty, who became notorious on the frontier for leading Indian raids against American forts and settlements.

[10]Nelson, A Man of Distinction among Them, Kindle ed., loc 2034.

[11]Heckewelder, A Narrative of the Mission of the United Brethren, 172.

[12]Ibid. White Eyes was increasingly isolated within his own tribe, or so he reported to the Moravian missionaries working among the Delaware. Herman Wellenreuther and Carola Wessel, eds., The Moravian Mission Diaries of David Zeisberger, 1772-1781 (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005), 440-441.

[13]Paul A.W. Wallace, ed., The Travels of John Heckewelder in Frontier America, 147.

[16]Wellenreuther and Wessel, eds., The Moravian Mission Diaries of David Zeisberger, 1772-1781, 446-447.

[17]Hand to Washington, September 15, 1777, Founders Online.

[18]Hand to Washington, November 9, 1777,” Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/?q=Ohio%20Period%3A%22Revolutionary%20War%22&s=1111311111&sa=&r=69&sr=, accessed November 13, 2018.

[19]Randolph C. Downes, Council Fires on the Upper Ohio (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1969), 212-214; Thomas L. Pieper & James B. Gidney, Fort Laurens, 1778-1779: The Revolutionary War in Ohio (Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 1976), 12-14. According to Pieper and Gidney, the idea originated with Morgan before Congress adopted it as policy.

[20]Gelelemend was the son of Benino, known among whites as Killbuck. Whites added the “John” and “Jr.” to distinguish the son from the father. Influenced by the Moravian missionaries on the Muskingum, Gelelemend eventually adopted Christianity and was baptized as William Henry. Like White Eyes, he also joined the Americans in their campaigns on the Ohio frontier, making him a veteran of the American Revolution. His gravesite has three markers listing all three names and noting his service as a scout to Col, John Gibson, who was second in command at Fort Pitt during the war’s later years.

[21]C.A. Weslager, The Delaware Indians: A History (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1972), 304; Colin G. Calloway, The Indian World of George Washington (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 267. The Delaware had been party to informal agreements between July 4, 1776 and September 1778, but the 1778 Treaty was formal, which distinguishes it from the others. The Treaty text is available at Yale Law School Library’s Avalon Project. “Treaty with the Delawares: 1778,” The Avalon Project, Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School, avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/del1778.asp, accessed November 14, 2018.

[22]Wellenreuther and Wessel, eds., The Moravian Mission Diaries of David Zeisberger, 1772-1781, 469.

[23]Downes, Council Fires on the Upper Ohio, 216-217.

[24]Morgan, quoted in Downes, Council Fires on the Upper Ohio, 216; Killbuck, quoted in Weslager, The Delaware Indians, 305.

[25]Weslager, The Delaware Indians, 306. Many had motives to kill White Eyes: whites who coveted Indian lands and opposed statehood; pro-war factions among the Delaware who felt betrayed by the Treaty of Fort Pitt; the British and western tribes that wanted to enlist the Delaware in the war on the Americans; or even internal Delaware leaders seeking to displace the elder statesman. It was also common for individual settlers on the frontier to kill Indians at the first opportunity, either out of blind revenge for raids on their families or neighbors, or simple reasons of greed. Morgan had his suspicions, but did not name the perpetrator[s], which suggests they were whites.

One thought on “The Treaty of Fort Pitt, 1778: The First U.S.–American Indian Treaty”

A captivating account of the complexities of the Native American and European alliances which in several instances appreared as state to state diplomatic relations! Further, your analysis of the different motivations within these groups helps dispel overgeneralizations and jingoistic myths. I especially appreciate the recommended biographies and other sources in your notes.