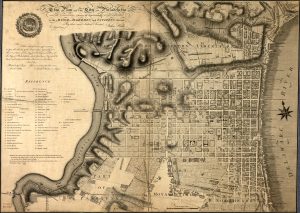

While conducting research for my essay on General Washington’s plight in the New Jersey short hills in the spring of 1777, I was fortunate to have stumbled upon a series of maps held at the David Library of the American Revolution in Washington Crossing, Pennsylvania. These maps, twenty reprinted copies in all, focus attention on the New Jersey towns the British occupied during the war. Reprinted for the bicentennial by the Library of Congress, the impressive manuscripts caught my imagination. And more so, the author of these maps, John Hills, caught my curiosity. Who was he? How did he do all of these surveys and sketches? I had never heard of Mr. Hills, but his talent was evident enough in his work. A couple of months later, I was having dinner at a relative’s house in Philadelphia where I happened to gaze upon the giant eighteenth century map of the city hanging on her wall. I examined the streets as they were in 1796, and checked off familiar landmarks that still exist in some form or another. And then I read the inscription and saw its author’s signature: John Hills. A strange feeling told me that this was no coincidence, and having not forgotten my initial intrigue with his maps, something inside me said, “This is your next subject to write about.”

My personal interest in maps is the reason that brought me to write about Mr. Hills. As a kid, I can remember being fascinated with studying the folded, colorful, gridded maps of New York City and Washington, DC. There was also a road trip down the Interstate 95 corridor to Florida that had me in the navigation seat the whole way. Reading a map correctly became a challenge I took seriously. Since my childhood, I have also been somewhat of a drawer. I have never had any professional training, and mathematics remains my kryptonite, but I often find sketching town or city plans to be quite relaxing. I suppose this continued fascination has helped make my journey with Mr. Hills that much more enjoyable. What little knowledge I have of professional drafting has been enhanced through the curious story of John Hills, a talented British surveyor and draftsman whom history seems to have forgotten. The intrigue kept building as I discovered more about him and his work. And I am very grateful that I did. The following represents a portion of what will become a full publication on the life and work of Mr. Hills.

The professions of surveying and being a draughtsman, someone who makes detailed drawings, usually fell within the realm of engineering. Formal training for British military engineers was conducted under the guidance of the Board of Ordnance in London, who used the Drawing Room at the Tower of London to train young cadets in engineering. The Royal Artillery Academy at Woolwich also trained cadets who could begin as early as the age of ten.[1] The work of a draughtsman, or draftsman in modern spelling, employed an established set of measuring scales. Typically, they used the following equations: three feet to an inch for small utilities like a drawbridge or gun carriage; ten feet to an inch for a magazine or battery; one hundred feet to an inch for a fort or larger battery; two or four hundred feet to an inch for the plan of a settlement or a town; eight hundred feet to an inch for a town and adjacent parts; and sixteen hundred feet to an inch for a coastline, small island or similar environs. The scales were not always accurate and details could vary. Draughtsman, in the military sense, typically used watercolors for their maps: light blue for water, red for buildings and troop movements, and pale buff for land elevations.[2]

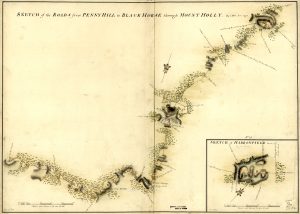

John Hills composed several regional maps of the 1778 British route northeastward from Philadelphia through southern New Jersey on their way to Sandy Hook. These numerous manuscript maps focus attention on main wagon roads throughout portions of southern New Jersey.[3] Profiles also include Monmouth Courthouse, depicting the positions of both armies during the battle on June 28th. Their detail and accuracy suggests that Hills surveyed and drafted these maps himself. The official record for Hills, however, does not begin until his commission on July 6, 1778 as an ensign in the 38th Regiment of Foot. The regiment had been in America since 1774, and although Hills’ promotion notice indicated that he had been a “volunteer” before being commissioned, there is no record of his service before he became an ensign.

The 38th Regiment was sent from New York to Rhode Island right around the time of Hills’ commissioning, but it appears that Hills stayed behind. Although an infantry officer, he is listed as one of three “extra draughtsman” assisting Capt. John Montresor, Chief Engineer to the British army, on September 19, 1778.[4] This is likely due to the shortage of engineers and cartographers among the British army in North America. None of the fifteen engineers taken into the Engineer Corps in 1775 were deployed to North America, and those that were present in America mainly specialized in constructing fortifications; they were not surveyors and mapmakers.[5] On October 10, 1778, Hills transferred from the 38th Regiment to the Royal Artillery, remaining at the same rank but now called 2nd lieutenant because he was in the artillery.

Only a few months later, Hills ran into trouble with a superior officer, Royal Artillery Capt. George Rochfort. The details are not known; on April 10, the commander of the Royal Artillery in America, Lt. Col. James Pattison, responded to a letter from Rochford, saying,

I am sorry any young Officer should be so wanting to himself as Lieut Hills appears to be, by the Report you sent me of his Conduct. The Good of the Service cannot possibly admit of such evident Contempt of Discipline being pass’d over unnotic’d. I must therefore desire you will put him under an Arrest, as soon as he returns to you Post, and unless he manifests by Letter a thorough Sense of Contrition for his Misbehavior, I shall be under a Necessity of bringing it to the serious Length of a Court Martial, the consquences of which he is not so unexperienc’d, as to be unaware of.[6]

Hills was not tried by a court martial, but he did resign his commission. The date of resignation was February 23, 1779, quite possibly back-dated to the time the unknown breach of discipline occurred, or event before. The young mapmaker’s military career, however, was not over. Before the year was over, he had won back the favor of his superiors. In November, Pattison wrote to Lord Viscount Townshend,

I take the Liberty to transmit herewith a Letter I received from Lieut. Hills, who I informed your Lordship had been, thro’ my Recommendations to Sir Henry Clinton, appointed a second Lieutenant of Artillery or Ensign in the 38th Regt; but the natural Bias of his Genius towards the professional Branch of Engineering has induced me (as Set forth in his Letter) to resign his Commission as Lieutenant of Artillery—which Resignation, the Commander in Chief has been pleased to accept; He is now, & has been for some time past, permitted to act as an Engineer in this Army, and has acquitted himself with Credit; His Ambition is to be introduced into the Corps of Engineers; if upon any Vacancy your Lordship shall be pleased to grant him that Favor, I am of Opinion he will not prove undeserving of it, and it will be esteemed as a great Obligation by General Matthew,[7] who has taken this Young Man much under his Protection. I shall leave him out of the Muster Rolls & Returns of the 4th Battalion for the ensuing Month.”[8]

Hills continued to work at mapmaking for the engineering department. He is listed on two separate returns as an assistant engineer in early 1780 under Alexander Mercer, Chief Engineer in New York.[9] Aside from an incident assaulting New Jersey Loyalist and judge David Ogden in May 1780, where Hills was ordered to issue a formal apology at Pattison’s urging, there is no further record of Hills’ conduct being a concern for the British.[10] While it appears that he did much of his work in New York, he certainly went to the front lines on at least one occasion, presumably to take sketches and surveys; he was wounded by American musket fire in one of the skirmishes near Springfield, New Jersey, in June 1780, but the extent of his injuries do not appear to have been serious.[11] In 1782, he was still listed among the assistant engineers in New York.[12]

In spite of this ongoing work, Hills never received a commission as an engineer. His next commission was as a 2nd lieutenant in the 23rd Regiment of Foot, the Royal Welch Fuziliers. This was not a promotion, being equivalent to the ranks he had held in the 38th Regiment and in the Royal Artillery, and it was once again an infantry commission, something to which there is no evidence that he was suited. It seems that his talents were great enough that the army was determined to find a way to keep him in pay no matter how incongruous the position. This unusual series of commissions has obscured his actual career, as there is no evidence that he actually served with any of the regiments in which he held ranks.

To add to the confusion, Hills prepared maps of places that he may never have visited, and depicting events in which he probably did not participate. Some later writings on New Jersey history have incorrectly stated that Hills composed maps before the Revolution. One of his earliest known works is a sketch of the Battle of Germantown in 1777 which has been criticized for its inaccuracy;[13] there is no evidence that he was with the army or in Pennsylvania at the time of the battle. A manuscript detailing the British and Franco-American fortifications at Yorktown in 1781 is far more accurate, but there is no proof Hills was there either even though the 23rd Regiment was.[14] It is likely that his regular presence in New York gave him the opportunity to produce maps of places he never saw for himself, resulting in a few instances of misidentification.[15]

Tracing his career is all the more difficult due to the spelling of his name in official records. Curiously, Hills is mentioned as “Hill” in various forms of correspondence and publications. Even some of his own publications have his last name spelled without the s; his maps bear variations including Lt. John Hills, Lieut. Hill, I. Hills, Asst. Engr. of the 23rd Regt (in period typefaces, the capital I is often used to represent J). The British Army Lists record only “John Hill” or “Hill.”[16] Very little is known about him prior to his service as an assistant engineer. The only known evidence of his life before the Revolution comes from a letter he wrote in 1798 that mentions his early training as a draughtsman for eight years before his service in the American Revolution.[17]

Nevertheless, John Hills produced nearly three dozen wonderful manuscript maps during the course of the war.[18] Some are noted for their simplicity while others show great attention to large sections of land. He spent time in the field surveying as well as in the map rooms, as indicated by inscriptions such as, “Surveyed by I. Hills, assistant engr.”; “From the original surveys in the possession of I. Hills. Lieut in the 23rd, Regt. Surveyor and draughtsman”; and “compiled from the Original Surveys in the Possession of John Hills, Lieut in the 23rd. Regt. Private Surveyor and Draughtsman to His Excellency the Commander in Chief.”[19] Many are handsomely colored and laid out, even if time has since aged and faded them. They give clear indication of the talent of British cartographers during the war. His particular focus on New Jersey in 1778, authoring two dozen original maps of the region, is the only instance of such attention paid to a state during the war. These were printed and engraved by William Faden of London in 1784.[20] Titled, A Collection of Plans &c. &c. &c. in the Province of New Jersey by John Hills Asst. Engr., Hills dedicated his work to his commanding officer, Sir Henry Clinton.[21]

Hills resigned from the army on April 7, 1784. He produced and published maps in America, advertising in New York newspapers as early as 1784, leaving doubt as to whether he had returned to Great Britain when the British army left New York in November 1783. His work would become the topic of discussion among such names as George Washington, Henry Knox, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and many others. He produced a detailed map of Sandy Hook that became valuable to the American government in 1799.[22] His contributions to the city of Philadelphia would redefine how the city viewed itself in the emerging zeitgeist as the republican center of the American experiment. His work during the war is now coveted by historical museums around the world, and provides necessary access into the world of eighteenth century military tactics and operations. His work continues to educate and inspire even though his life had faded, like an old map, into obscurity.

[1]The Board of Ordnance was commanded by George Townshend, master general. After being displeased with the abilities of cadets from the academy at Woolwich, Townshend refocused to educating cadets in the Drawing Room at the Tower of London. The two places were the cadet schools for future officers in the Engineers Corps. Of the fifteen engineers who graduated from the Drawing Room between 1775 and 1781, none served in America during the Revolutionary War. Douglas W. Marshall and Howard H. Peckham, Campaigns of the American Revolution: An Atlas in Manuscript Maps (Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press, 1976), 15.

[2]Peter J. Guthorn, John Hills, Asst. Engineer (Brielle, NJ: Portolan Press, 1976), 25, 45. Originally taken from Whitworth Porter’s History of the Royal Engineers.

[3]Some of the local maps that Hills produced focus on the towns of Crosswicks, Haddonfield, Mount Holly, New Brunswick, Bonhamtown, and Freehold, New Jersey. These are all dated June 1778, and are part of the collection published by William Faden in 1784.

[6]James Pattison to George Rochford, New York, April 10, 1779, in James Pattison, “The Official Letters of Major General James Pattison, Commandant of Artillery,” Lewis Morris, ed.,The New York Historical Society Collection of 1875 (New York: Publication Fund Series, 1876), 35.

[7]Edward Mathew was a British major-general who saw action throughout the New York-New Jersey arena. Hills would remain under his “protection” during June 1780 as skirmishes led to the Battle of Springfield. Hills produced a handful of maps of the area, and was injured by American musket fire.

[8]The letter by Hills has not been located. “The Official Letters of Major General James Pattison,” 136-138.

[9]The dates of the returns are January 14, 1780 and February 25, 1780. Peter J. Guthorn, British Maps of the American Revolution (Monmouth Beach, NJ: Philip Freneau Press, 1972), 24.

[10]In a letter dated May 24, 1780, Maj. Gen. James Pattison’s subordinate wrote to Lieutenant Hills, charging him with assaulting a “refugee,” but understood Hills likely was unaware the person’s identity. He recommended on behalf of Pattison that, “you will make him [Ogden] such an apology as one Gentleman ought to do another, and thereby prevent this matter being brought to a more disagreeable Issue.” “The Official Letters of Major General James Pattison,” 396.

[11]“Lt. George Mathew’s Narrative,” Historical Magazine, I (1857), 102-106.

[12]A return from 1782 lists Robert Morse, along with three others in the Engineer Corps, in New York. Thirteen assistant engineers are listed, Hills among them. Marshall, Campaigns, 37.

[13]Justin Winsor, quoted in Martin P. Snyder, City of Independence: Views of Philadelphia Before 1800 (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1975), 106-107.Author John W. Shy, critical over the inaccuracies of the roads presented on Hills’s Germantown map, also criticized his inaccuracies on his map of Monmouth Courthouse. Marshall, Campaigns, 133.

[14]The map of Yorktown is very similar to others produced by British and French engineers. It is possible Hills copied from the British sources.

[15]Elizabeth Stow Brown, Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society, Third Series, Volume IV, No. 2, 1902-1903 (Paterson, NJ: The Press Printing & Publishing Company, 1906), 67.

[16]Worthington Chauncey Ford, British Officers Serving in the American Revolution 1774-1783 (Brooklyn, NY: Historical Printing Club, 1897), 6.

[17]John Hills wrote a letter to John Jay, governor of New York, on April 14, 1798 to inquire if his services could assist in fortifying Governor’s Island and Fort Jay in the New York Harbor. Preparations were underway across the east coast in case of war with France and England. In the letter, Hills states that he had formal training both at the Royal Academy at Woolwich and at the Tower of London. He also states his professional skills as a draughtsman began in 1767. There are no surviving records from the Royal Academy prior to 1790, and inquiries with the British National Archives have not turned up John Hills receiving training in the Drawing Room at the Tower of London. It is possible Hills did indeed receive an education at these places. Or it is possible he did not, and fabricated his credentials in order to boost his reputation. What is certain is that his interest and his capabilities were enough, whether he had formal training or not, to convince the British army he was a formidable mapmaker during the war. John Hills to John Jay, April 14, 1798, The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, Volume 22. Library of Congress.

[18]John Hills signed his wartime manuscripts under several signatures. Most common are Lieut. Hills or I. Hills, Asst. Engr. In the Latin alphabet, the letter I is in the place of the letter J. Thank you, Indiana Jones.

[19]Plan of Paulus Hook shewing the works erected for its defence. Surveyed by I. Hills, assistant engr. July 1781. William Clements Library; A Plan of the Roads between Hackinsack and the North or Hudson’s River in the Province of East New Jersey, From the original surveys in the possession of I. Hills. Lieut in the 23rd, Regt. Surveyor and draughtsman.National Archives of Great Britain; A Map of Part of the Province of East Jersey containing Part of Monmouth, Middlesex, Essex and Bergen Counties compiled from the Original Surveys in the Possession of John Hills, Lieut in the 23rd. Regt. Private Surveyor and Draughtsman to His Excellency the Commander in Chief 1782, National Archives of Great Britain.

[20]New Jersey is the only state to have been given such attention by a draughtsman during the Revolutionary War.

[21]A complete collection of the manuscripts of A Collection of Plans &c. &c. &c. in the Province of New Jersey by John Hills Asst. Engr. are held at the Library of Congress. Originally, Henry Clinton retained these after their publication in 1784. They were eventually passed down to his heirs, and purchased from them by the Library of Congress in 1882. For the bicentennial in 1976, they reprinted a full set of the collection, which can now be found at the David Library of the American Revolution in Washington Crossing, Pennsylvania. Accompanying these reprints, author Peter J. Guthorn produced a short cartographical-biography on John Hills. Though incomplete in many facets, the publication served as the starting point for this project. Guthorn, John Hills.

[22]Alexander Hamilton and John Jay exchanged several letters in late 1798 and early 1799 discussing whether they should purchase the map of Sandy Hook from Hills.

6 Comments

That is a very good article Adam.

I like maps and surveyors too.

Karen in Canada

Hi Karen,

Thank you for the kind words. I am glad you enjoyed a small slice of the story of John Hills. Much more to come!

Happy New Year.

Adam

As I am researching Samuel Holland and his mapping projects, I found your article quite interesting and there would appear to be some parallels between some of your comments and some of the information I am finding in my research. For example, I have come across similar happenings with regard to Hills’ commissions in the artillery and in infantry regiments. Holland and some of the men who worked under him spent time in artillery units which is not that surprising. However, what is mildly surprising is that Holland and many of his crew came from the 60th or Royal Americans among other line units. There is some work done by Peter Guthorn dealing with regimental attachments of mapmakers during the Revolution in which he found that of ninety British cartographers, thirty-three (36.6%) held rank in line or cavalry regiments. Only fourteen held post as headquarters mapmakers or as part of the mapmaking corps. I suspect much of this practice can be attributed to administrative and/or financial necessities.

It also is clear from my research that British documents show a high number of civilian or volunteer surveyors, cartographers and draughtsmen. Part of that can probably be attributed to the use of Loyalists in the Guides and Pioneers but it would also account for Hills’ still being around after leaving the military.

Lastly with regard to your comments, from what I have found, mapmakers often created maps of places they never visited. They simply used measurements and notes gathered by other surveyors in the field. Holland actually had as many as five surveying crews working in the field for him.

Mr. Barbieri,

Thank you for the response, and the insightful information you have provided. That is quite exciting to hear you are profiling Capt. Holland! In my larger profile of Hills that I am currently working on, I do briefly mention Holland as a formidable cartographer prior to the Revolution. As you state, it is likely draftsman often took what manuscripts and surveys were available, and made new interpretations with them. I cannot find any evidence (yet) of whether Hills used a surveying crew(s) in his post-war years as a surveyor and draftsman in Philadelphia, but it is likely given the size of the projects he worked on. Also, yes, it is interesting how their military lives ran somewhat parallel. It doesn’t appear Hills enjoyed the Artillery, but I speculate the experience might have played into his reprisal in the 1790s while working for Henry Knox in Massachusetts and in Maine.

I am sure you have numerous sources, but from my own, I can point you to the following regarding Capt. Holland:

John R. Sellers; Patricia Molen Van Ee, Maps and Charts of North America and the West Indies 1750-1789: A Guide to the Collections in the Library of Congress, p. 477 (index with several manuscript listings)

Douglas W. Marshall; Howard H. Peckham, Campaigns of the American Revolution: An Atlas of Manuscript Maps, pp. v, 15, 37.

Peter J. Guthorn, John Hills, Asst. Engr., pp. 27, 31 (Holland is listed as the source of surveys Hills used for his “Plan of the Attack of the Forts Clinton & Montgomery upon Hudson River….; and “Plan of Perth Amboy from an Actual Survey”). Holland’s name appears alongside a Verplank and Metcalf (both not identified) for the Forts C/M survey, and James Grant, who worked for Holland, is credited for the Perth Amboy survey.

Holland is given a sizable profile in Guthorn’s British Maps of the American Revolution, pp. 27-29, too.

Thank you again for reading. Happy New Year.

Adam

I especially love what I call “the side stories” of our history and this article is special to me as I have been married to a Professional Land Surveyor for the past 47 years. And long after they are gone there are physical ‘monuments’ to their work.

Hi Jonne,

Thank you for the kind words. I am happy to see you were able to make a personal connection to the story. Much more to come regarding Mr. Hills, I promise!

Happy New Year.

Adam