On July 2, 1778, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts hanged Bathsheba Ruggles Spooner and Continental soldier Ezra Ross, together with British soldiers Sgt. James Buchanan and Pvt. William Brooks. They had been convicted of the murder of Bathsheba’s husband, Joshua Spooner, in “the most extraordinary crime ever perpetrated in New England.”[1] The trial was the first capital case of the new nation. Bathsheba Ruggles Spooner, favorite daughter of the Loyalist Timothy Ruggles, was the first woman to be hanged in the United States of America following the declaration of independence. The execution of the five-months pregnant woman reflected strong anti-Loyalist sentiment, and “personal vengeance on the part of a high-ranking official was also a motive in that infamous hanging.”[2]

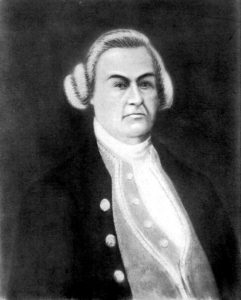

Timothy Ruggles, Bathsheba’s father, was the fifth generation of the Ruggles family in the New World. Born in 1711, he graduated Harvard College in 1732 and established a law practice. In 1753 he moved his family to a 400-acre farm in the new town of Hardwick, west of Worcester, Massachusetts. Ruggles played a major role in the French and Indian War and was awarded the rank of brigadier general. In 1762 he was appointed chief justice of the court of common pleas in Worcester. Ruggles served in 1762 and 1763 as speaker of the Massachusetts General Court. The young John Adams, who trained in the law while living in Worcester, admired the haughty judge Ruggles’ quickness of mind, the strength of his thoughts and expressions, and the boldness of his opinions. “His honor is strict . . . People approached him with dread and terror,” wrote Adams in 1759. At the height of his career, Timothy Ruggles was appointed president of the Stamp Tax conference held in New York City in October 1765, but he refused to add his signature to a petition critical of the king’s government for imposing taxes without the knowledge and approval of his subjects. Ruggles saw in the document the seeds of rebellion and bloodshed, and opposed it out of a sense of duty. For this act the General Court of Massachusetts censored him; his once-sterling reputation plummeted. “His behavior was very dishonorable. [Ruggles] is held in utter contempt and derision by the whole continent,” wrote John Adams in 1775.[3] Timothy Ruggles was once “one of the most distinguished citizens of the Province of Massachusetts Bay.” But after he declared his allegiance to the king he was regarded “as the worst of traitors and his name held in the utmost abhorrence. . . . No man in Massachusetts was regarded as so inimical to the cause of rebellion as general [Timothy] Ruggles.” Many of his erstwhile friends and family opposed him, including his brother Benjamin who came to regard him as “an enemy of his country.” Five of his nephews, including his namesake Lt. Timothy Ruggles, joined general Washington’s army. In 1774 his Hardwick home was attacked and his cattle poisoned. Ruggles accused the rebels of using the pretense of “being friends of liberty [to commit] enormous outrages upon persons property . . . of his Majesty’s peaceful subjects.” Threatened in central Massachusetts, Ruggles rode the one hundred miles to Dartmouth “but patriots would not tolerate his presence anywhere,” forcing him to seek shelter in British-occupied Boston.[4] Ruggles established the Loyal American Associators to protect Loyalists from abuse and to openly display allegiance to the crown. He gathered together only 200 followers, mainly wealthy Boston merchants. In March 1776 he departed Boston with the British fleet and followed the army and navy to Staten Island to further aid the British cause.[5] In September 1778, the Massachusetts Banishment Act listed 300 people accused of joining the enemy. After former governors Thomas Hutchinson and Francis Bernard, and former lieutenant governor Thomas Oliver, the name of Timothy Ruggles is the fourth on the list of traitors. Massachusetts confiscated all Timothy Ruggles’s properties.[6]

Four of Ruggles’s daughters, including Bathsheba, had married before the rebellion and remained in America. Born in 1746, Bathsheba wed Joshua Spooner on January 15, 1766 and went to live with him in Brookfield, eleven miles southeast of her parents’ homestead in Hardwick. Joshua Spooner was “in character a feeble man,” abusive and a heavy drinker. The beautiful Bathsheba was intelligent and high-spirited, but “her passions had never been properly restrained.”[7] By 1774 she was the mother of four children but separated from her beloved Loyalist father and trapped in a loveless marriage to Joshua Spooner, for whom she had developed an “utter aversion.”

In March 1777, a young soldier named Ezra Ross came to Brookfield. The sixteen-year-old Ezra and four of his brothers from a respectable Ipswich, Massachusetts, family had joined the American army at the start of the war. After the Siege of Boston and the British evacuation in March 1776, Ross followed Gen. George Washington to New York and to Trenton, New Jersey. After completing his enlistment, Ezra set out by foot on the arduous 300-mile journey to return to his home in Ipswich. Passing through Brookfield he had “a severe fit of illness” and was taken into the Spooner home where Bathsheba showed him “every kindness” on the path to recovery. Besotted by Bathsheba, the handsome youngster came again to Brookfield in August on his way to support the Americans at Fort Ticonderoga. After the American victory at Saratoga, young Ezra made haste to the Spooner home and was often seen out riding with the beautiful Bathsheba, a woman twice his age. Passions flowed and Bathsheba became pregnant by young Ezra. With adultery considered sinful and divorce well nigh impossible, Bathsheba plotted to get rid of her husband. Promising to marry her young lover, Bathsheba asked Ezra to poison Joshua Spooner by pouring aqua fortis (nitric acid) into his grog. Ezra refused and left Bathsheba to her fate.[8]

The British army that surrendered at Saratoga, meanwhile, gave up their arms, crossed the Hudson River and marched into Massachusetts “to be quartered in, near or as convenient as possible to Boston” while awaiting their embarkation back to Europe. The march across New England in October and November was arduous; conditions in the Berkshires were tough with driving rain, mud and then snow. Carts broke down, “others stuck fast, horses tumbling with their loads of luggage.”[9] Along the way to Boston, a large number of Burgoyne’s troops deserted, among them two soldiers of the 9th Regiment of Foot. James Buchanan, a Scottish sergeant in his early thirties, was “of decent education and good appearance” and had left his family behind in Montreal when he set out on the fateful 1777 campaign.[10] William Brooks was from Wednesbury, Staffordshire, was twenty-seven years old, and had had a bizarre experience during his regiment’s voyage to America in 1776:

April 20th. Our ship sailing at the rate of five miles an hour, a soldier whose name was Brooks, leaped off the forecastle into the ocean; the vessel in a moment made her way over him, and he arose at the stern. He immediately with all his might, swam from the ship. The men who were upon the deck alarmed the captain and officers, who had just sat down to dinner; the ship was ordered to be put about, and the boat hoisted out, and manned, the unfortunate man was soon overtaken, and it was with difficulty that the sailors could force him into the boat. When he was brought back he was ordered between decks, and a centinel placed over him; the next morning he was in a high fever, and continued very bad the remainder of the voyage. The fear of punishment was the cause of this desperate action, as the day before he had stolen a shirt from one of his messmates knapsacks.[11]

Early in February 1778, Buchanan and Brooks were passing through Brookfield on their way to Springfield in search of work. Desperate to kill her husband before her pregnancy showed, Bathsheba sent her servant to invite the bedraggled British soldiers into her home for food, rest and comfort. With Joshua Spooner away on a business trip, Bathsheba ensnared Buchanan and Brooks with a warm welcome into an American home in the midst of the war. They were delighted to learn that Bathsheba “had a great regard for the [British] army, as her father was in it, and one of her brothers.” Bathsheba seduced Brooks the way she had earlier seduced Ezra Ross. Brooks was seen with his head laid “upon Mrs. Spooner’s neck and, oftentimes, his hands round her waist.” Offering the British deserters one thousand dollars, clothing and the alluring prospect of sex, Bathsheba “made a direct proposal to these entire strangers to murder her husband, which they agreed to do on the first favorable opportunity.” Enjoying great comfort for eleven days in the grand Spooner home, Buchanan and Brooks little thought “of the bait the seducer of souls was laying for us.”[12] Circumstances changed dramatically when Joshua Spooner returned; angry to find the British soldiers in his home, he ordered them to leave. Bathsheba concealed them in the barn and provided them with food, to await the opportunity to murder Joshua Spooner. On March 1, Ezra Ross “either by accident or design” arrived at the Spooner house. He had never met Buchanan or Brooks before, but the beguiling Bathsheba inveigled him into the murder plot.

Joshua Spooner spent that evening with his pals at Cooley’s Tavern, a quarter-mile from his house. He left the tavern between eight and nine o’clock. Returning home he was attacked by William Brooks, who beat him to death while Buchanan and Ross were “aiding, abetting, comforting and maintaining the aforesaid Brooks.” Bathsheba “invited, moved, abetted, counseled and procured” the murder of her husband. The men dragged Joshua’s body out of the house and dumped it down the well (Bathsheba planned to say that her husband had gotten up during the night to draw water from the well and had accidently fallen in and drowned), but they left telltale evidence such as Joshua’s crumpled hat, blood on the snow, footsteps, and heaps of snow next to the well. Bathsheba and the three men burned Joshua Spooner’s bloodstained clothing. Bathsheba opened her family’s money box and gave the men a down-payment of two hundred dollars together with Joshua’s fresh clothing, and off the three fled into the night, making their way to Worcester.[13]

The following day, Buchanan, Brooks and Ross were apprehended. Between them they had Joshua Spooner’s shirt, jacket, breeches, saddlebags, his ring, watch and a pair of silver buckles with Spooner’s initials on them. The men also had the wads of money given them by Bathsheba. She and the men readily confessed to the murder and were clapped into prison. Their trial took place in Worcester on April 27, with chief justice William Cushing officiating, aided by associate justices David Sewall and James Sullivan (future governor of Massachusetts), with a jury of twelve men. Leading the prosecution was attorney for the Commonwealth Robert Treat Paine (a signer of the Declaration of Independence). Levi Lincoln (future lieutenant governor of Massachusetts, and a distant relative of Abraham Lincoln) was the attorney for the accused.

Lincoln reminded the jury that the case was “the first capital trial since the establishment of the government.” He entreated the jurors to put aside “all feeling and prejudice . . . all political feelings.” “This doubtless,” wrote Peleg Chandler, “was an allusion to the vibrant prejudice at that time in Massachusetts against Mrs. Spooner’s father on account of his political course.” Born of high rank, well educated and accomplished, the mother of four children and now four months pregnant, Bathsheba had been trapped in an abusive marriage. With her father and brothers aiding the enemies of the nation, she had nowhere to go and had orchestrated “a most horrible crime.” Bathsheba was “not in a state of mind which rendered her guilty,” claimed Lincoln.

The whole murder trial took a mere sixteen hours. Despite the insanity plea, the jury found Bathsheba Ruggles Spooner, Ezra Ross, James Buchanan, and William Brooks, guilty of murder. Chief Justice William Cushing pronounced the penalty: death by hanging. Execution was set for June 4.

Ezra Ross’s aged parents submitted an appeal to save his life. “At the first instance of bloodshed” they had sent five sons to fight for the American cause. Four sons fought at Bunker Hill, and three (including Ezra) had marched southwards with General Washington. One of their sons was killed in battle. The Ross family claimed that their boy, far from the security and guidance of his family, was seduced “by a lewd and artful woman” to take part in the gruesome murder.

Bathsheba Ruggles Spooner made no appeals to save her own life. At the close of May 1778, she informed the court that she “was soon to become a mother [and] the child I bear was lawfully begotten. I am earnestly desirous of being spared till I shall be delivered of it.” Execution was postponed to allow time for Bathsheba to be medically examined. Believing that Bathsheba sympathized with her Loyalist father in his politics, the two male-midwives and twelve matrons who examined her concluded that she “was not quick with child.”[14] Deputy secretary John Avery Jr. signed the final warrant of execution set for July 2, 1778. An ardent patriot and member of the Sons of Liberty, Avery was guided by a deep animosity towards Bathsheba’s father, Timothy Ruggles.[15]

On the appointed day, “an immense throng of people” numbering 5,000, coming from near and far, assembled in Worcester to witness the hanging of the four murderers. Escorted by an armed guard of one hundred men, the prisoners were brought out by cart to the hanging place, close to the courthouse where Timothy Ruggles had served as chief justice. After the three men were hanged, the rope was place around Bathsheba’s neck. With her face covered, Bathsheba acknowledged her guilt. Taking the sheriff William Greenleaf by the hand, she said: “My dear Sir, I am ready. In a little time I expect to be in bliss and but a few years must elapse when I hope I shall see you and my other friends.” And she was hanged till she was dead. Post-mortem revealed a five-month, perfectly formed male fetus, an innocent victim put to death with the guilty.

Whether Bathsheba Spooner was insane, and whether the state of Massachusetts wrongfully hanged a five-months pregnant woman to punish her Loyalist father, have long been debated. In 1889, Samuel Swett Green offered evidence that “for a long time Bathsheba had been a markedly eccentric woman” and her daughter (also named Bathsheba) “had been hopelessly crazy for many years.”[16]

Timothy Ruggles was in New York when his daughter Bathsheba was hanged. Well into his sixties, he no longer played a significant role in the affairs of his country. With the British defeat in 1783, Ruggles and three of his sons, Timothy Jr., John, and Richard, went into exile to Nova Scotia. In gratitude for his loyalty and to compensate him for the loss of his Massachusetts properties, the British government awarded him 1,000 acres near the town of Wilmot in Annapolis County. Timothy Ruggles chose Resurgam (I will rise again) as the motto of Nova Scotia. There he lived out the remainder of his life, dying in 1793 at the age of eighty-two.

[1]Boston Independent Chronicle, March 12, 1778.

[2]Deborah Navas,“New Light on the Bathsheba Spooner Execution,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Third Series. Vol. 108 (1996), 115-122.

[3]Charles Francis Adams, The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States,Volume 4 (Boston: Little & Brown, 1857), 33.

[4]Ray Raphael and Marie Raphael, The Spirit of ’74; How the American Revolution Began. (New York: New Press, 2015), 87-88.

[5]Henry Stoddard Ruggles, General Timothy Ruggles (Boston: Privately Printed, 1897).

[6]James Henry Stark, The Loyalists of Massachusetts and the Other Side of the American Revolution (Boston: James H. Stark, 1909), 225-228.

[7]Peleg William Chandler, The Trial of Bathsheba Spooner and Others. Volume 2 (Boston: Timothy A. Carter, 1844.

[8]Deborah Navas, Murdered by his Wife (Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001).

[9]Thomas Fleming, “Gentleman Johnny’s Wandering Army,” American Heritage, December 1972, Volume 24, Issue 1.

[10]“The Dying Declaration of James Buchanan, Ezra Ross and William Brooks,” in Navas, Murdered by his Wife, 211-218.

[11]Don N. Hagist, A British Soldier’s Story: Roger Lamb’s Narrative of the American Revolution (Baraboo, WI: Ballindalloch Press, 2004). There was only one man named Brooks in the regiment at that time. Muster rolls, 9th Regiment of Foot, WO 12/2653.

[12]Chandler,The Trial of Bathsheba Spooner, 35.

[14]Herbert M. Sawyer, History of the Department of Police in Worcester, Massachusetts from 1874-1900 (Worcester: Worcester Police Relief Association, 1900), 26.

[15]Navas, “New Light on the Bathsheba Spooner Execution,” 1996.

[16]Samuel Swett Green, Bathsheba Spooner: incidental remarks made at the annual meeting of the American Antiquarian Society held in Worcester, October 22, 1888 (Worcester: Charles Hamilton, 1889).

11 Comments

This is an interesting account of a murder and capital trials taking place in 1778, described as “the first capital trial[s] since the establishment of the government,” at a time when there was vehement oppression to Loyalists. They are also interesting for the involvement of British soldiers with a civilian female being tried in a civil, and not military, court for, what I assume was common law, murder.

While these four defendants were being tried on April 27, 1778 and sentenced to execution, one hundred miles away in Bennington, Vermont, British soldier David Redding was tried on June 4 and, again, on June 6 because of errors in the first trial, for unstated “inimical conduct.” This was an extra-legal proceeding being conducted by an unrecognized civilian “authority” (i.e., a breakaway region of Albany County called the Hampshire Grants), under the auspices of a so-called “states attorney” in the personage of Ethan Allen. Redding was predictably found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging on June 11, three weeks before the Worcester defendants.

The interplay between civilian and military defendants and the way that the law was administered both in civil and military courts (consider Nathan Hale in 1776) is interesting to consider. As Redding’s execution has been characterized as nothing more than a premeditated lynching, the palpable hatred for Loyalists and British soldiers that seeps from these various proceedings raises serious questions about idealized visions of the rule of law that the colonists practiced. It also raises questions of just how far rushed, primitive notions of due process were allowed to interfere in their disposition as emotion was allowed to invoke speedy executions instead of the burdens imposed by the alternative of the incarceration of sentenced prisoners.

Practicality and not the compassionate administration of the law seems to have ruled in these days. It was, indeed, a vicious time.

A small note on this: While Brooks and Buchanan were truly British soldiers in that they were born in the British isles and enlisted in a British regular regiment before the war began, Redding was a Loyalist from New York who joined Burgoyne’s army on its 1777 campaign.

A good point, Don (Redding was a member of the Queen’s Loyal Rangers), but one that I do not think would not have meant anything to the Worcester civilian court choosing to take the drastic action of executing British soldiers. I think that is what stands out, from a legal standpoint anyways, in this article; notwithstanding the death of an infant who had no legal standing cognizable in a colonial court.

Redding is also interesting for no matter what his status was, Ethan Allen was going to see to it that he was killed one way or the other. Some have tried to exonerate Allen’s leading in this lynching, but as Redding’s biographer, John Spargo, relates, his execution was nothing “better than a discreditable travesty of justice.”

It seems unlikely that she was actually pregnant. She had given birth to four children previously. The likelihood that she was not showing her pregnancy by five months in her fifth pregnancy seems difficult to imagine. There is the possibility that menopause had hit and she assumed that she was pregnant or she was just using an invented pregnancy to manipulate Ross. Midwives of the era were a lot more knowledgable than they have been historically given credit for.

I had previously heard of “pleading one’s belly” to avoid a death sentence until after a child was born but I had never read about the “quick child” portion of the law until the great answers here. Very interesting distinction. I do believe the JAR readers are some of the most informed commenters I have ever encountered.

Pleading the belly was a process available at English common law at least as early as 1387.

The plea did not constitute a defense, and could only be made after a verdict of guilty was delivered. Upon making the plea, the convict was entitled to be examined by a jury of matrons, generally selected from the observers present at the trial. If she was found to be pregnant with a quick child (that is, a fetus sufficiently developed to render its movement detectable) the convict was granted a reprieve of sentence until the next hanging time after her delivery

Now that is what I call a ripping yarn! Was a surgical post-mortem performed to confirm the pregnancy? Whatever became of her remaining 4 children, one of whom was apparently reported to have been “crazy,” and what were Bathsheba’s reported eccentricities? And did her father and brothers grieve her? Did the scandal affect their family’s fortunes? (Ruggles seems to have prospered in Nova Scotia.) This tale has the makings of a terrific movie!

No, she was indeed pregnant. The key is in the phrase “quick with child”. That’s a reference to how far along she was in the actual pregnancy, somewhat in terms of viability of the fetus. The midwives were determining whether the fetus has “quickened” or not–not trying to determine whether or not she was pregnant.

You are correct, quicking is the point at which movement is detected and is the moment when the law in colonial times identified the child as a human being eligible for protection. Aborting a child prior to quickening (or, in this case, hanging its mother) was a fact of life and an unremarkable event. But interfering with a fetus post-quickening is when the law assigned liability to anyone doing so. This remained so until around the 1820-1840 time period when states started to pass laws prohibiting abortion prior to quickening (here in Vermont, our first abortion law was created in 1846).

Incredible story. I wonder to what extent mercy was available to loyalists or even relatives of loyalists. Her guilt was quite clear, but I would think that pregnancy would merit consideration of some sort of leniency in those times. Guess not in this case.

Interesting story. What is the source for the post mortem that revealed a fully formed infant in the womb of Bathsheba Ruggles? If such was actually performed then the comment above by Dan is irrelevant to the story.

I wrote “The Most Extraordinary Murder” from the perspective of the Revolutionary War and the hostility toward loyalists, such as Bathsheba Spooner’s father, Timothy Ruggles. The erudite correspondents of JAR are equally interested in Bathsheba’s pregnancy, whether she was “quick with child”, who examined her and whether a post-mortem examination took place. On June 11, 1778 Bathsheba was examined by two male midwives and twelve matrons who declared that “she was not quick with child.” The male midwives were physicians; the Harvard graduate Dr.Josiah Wilder, son of colonel Joseph Wilder who fought with the British from 1758-1763 to wrest Canada from the French, and Dr. Elijah Dix, grandfather of the mental health reformer Dorothea Dix. On June 27, Drs. Wilder and Dix, aided by Dr. John Green, re-examined Bathsheba and concluded that she was “now quick with child”. The twelve matrons , however, disagreed and wrote that Bathsheba “is not even now quick with child”. The opinion of the three doctors was disregarded and the exucution of Bathsheba and the three soldiers took place on July 2. Dr. Elijah Dix later moved to Boston to become a prominent physician and drug store owner. I leave it to another intrepid historian to describe midwifery and the state of medical practice in Revolutionary America.