The American Revolution was in effect a civil war. It included all the heightened acrimony associated with one. In what became the United States, there was hostility and outright violence between those supporting the rebellion (“Patriots”) and those against it (“Loyalists”). Soldiers and families alike faced social ostracism, physical danger, loss of property, and for many, bitter exile for staying loyal to the Crown.

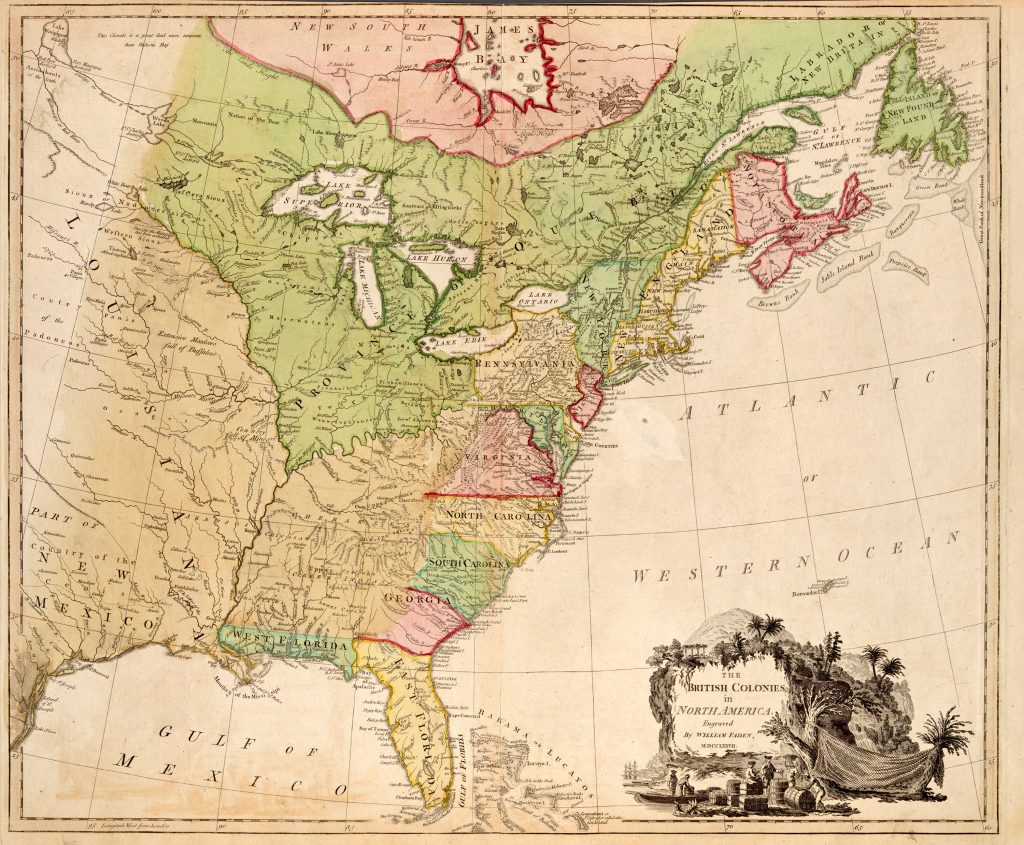

The conflict wasn’t confined to the thirteen colonies; it also spilled into other parts of British North America, primarily the northern colonies that would eventually become Canada (for simplicity, I’ll call them Canada throughout this article). American intentions were to try to incorporate Canada as a fourteenth colony or, failing that, to neutralize the military threat to the thirteen colonies posed by the British presence along the border.

In Canada, the rebellion failed, at least as measured by the first goal. Early attempts by Canadian merchants to assemble a delegation to the Continental Congress were unsuccessful. The sticking point was the non-importation act, the Continental Association, which the merchants feared couldcause them to lose the lucrative fur trade to Canadians who stayed loyal.[1] Ironically, Canada would become an exile destination for many American Loyalists and would eventually achieve its independence through much more peaceful means.

The attempt to incorporate Canada into the Revolution resulted in an interesting dynamic: the Patriots in British Canada in many ways received the same treatment as Loyalists had in the “lower thirteen” colonies. Much has been written about the Patriot-Loyalist conflict in America. The flip-side of this, how that conflict impacted Patriots north of the border, can be seen in two men – one with British roots, John Allan, and the other a French-Canadian, Clement Gosselin. How was it for them to live the “Loyalist” experience, so to speak, in Canada?

John Allan

John Allan was born on January 3, 1746, in Edinburgh Castle, Scotland. His father, William, was an officer in the British army. In 1749, the elder Allan took advantage of a British offer to relocate to Nova Scotia, continuing as an officer there. When the British won French Quebec as part of the treaty settling the Seven Years War, William received land in Nova Scotia, territory made available through the forced relocation of French Acadians and local Indian tribes.

Following his marriage to Mary Patton on October 10, 1767, young John received a large piece of property from his father, a 350-acre farm near Cumberland, Nova Scotia. In addition to farming, he engaged in the fur trade with several Indian tribes. He also was active in local politics, holding offices such as justice of the peace, clerk of the session, and clerk of the Supreme Court. In the spring of 1770, he was elected representative to the provincial assembly in Halifax, a position he held until his seat was declared vacant for non-attendance in 1776.[2] By that time, he was on the run.

Allan seemed to be in a settled and prosperous position, with little to gain by participating in the spread of the American rebellion to Canada. Furthermore, his father was still in the British army. Yet despite all this, he fell into the rebellious camp during his formative years. This may have derived partly from his education; he attended school in Massachusetts, as did many of the sons of British officers in the northern colonies. There were few educational opportunities yet in lightly populated Nova Scotia.

Then there was the issue of the Quebec Act of 1774, one of the British actions the Patriots considered as part of “The Intolerable Acts.” This Act was viewed by the Patriots as an attempt to placate the French-Canadians, and its most problematic provisions were tolerance for Catholicism and extension of the borders of Quebec. Catholicism, always a sore point with the British, became one for the Patriots too. The extension of the boundaries of Quebec into parts of Pennsylvania, Ohio, and the Great Lakes region, when combined with other British possessions, effectively hemmed in the thirteen colonies, preventing future expansion. These territories, especially Ohio, represented land the American revolutionaries craved or in some cases even had claims on already. Thus, the Act created a major threat to America’s expansionist dreams (an early version, though the term had not yet been coined, of Manifest Destiny).

Allan was frustrated in promoting the Patriot cause as he could not encourage enough Nova Scotians to join him. For the rebellion to succeed, he would need help from New England.[3] This prompted him to pen an anonymous letter dated February 8, 1776, from a “Citizen of Nova Scotia” to George Washington, requesting support. In this letter he tried to convince Washington of the dire state of liberty in Canada and to convince him that despite the American failure at Quebec in late 1775 the British could still be defeated – if Washington, who obviously had his hands full at the time, could lend the necessary military and monetary support:

so much will suffice as will give your Excellency an Idea of the Rise of our Impending Calamity if providence does not stirr up some means to Avert it—the Generality of the province as I before mentioned sympathisd with the Colonies—the Least Encouragment or Oppertunity woud have Excited the people to Join in the Defence of the Libertys of America, always Rejoiceing when the[y] heard any flying Report that an Invasion was intended.[4]

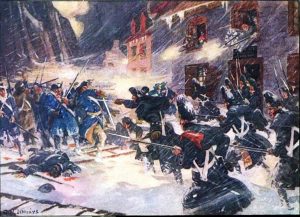

He knew the British would end the siege of Quebec once the ice broke on the St. Lawrence, allowing relief parties through. Thus, time was of the essence: “The people in Genl have Great familys which will Occation a lemantable sceene shoud British Troops Arive here before any succour Comes from your Excellency—We woud Greatly Rejoice Coud we be able to Join with the other Colonies, but we must have other Assistance before we Can Act Publickly,” wrote Allan.[5] Unfortunately, help did not come soon enough. British forces arrived in the spring, and the siege of Quebec ended.

Allan’s militancy for the American cause continued, resulting in him being accused of treason, with a £100 price placed on his head. Facing imminent arrest, he left Nova Scotia for the Maine territory (Maine was not yet a state) in August 1776. He had built a close relationship with the Mic-Mac Indians while in Nova Scotia, and through that friendship Maine became his refuge; has was accompanied there by several tribesman.[6] After arriving in Maine, Allan worked to assemble a pro-rebellion force to attack Nova Scotia. As for the Indian tribes of eastern Maine, he sought to bring them to the American side, or at least keep them neutral.

Left behind in Nova Scotia at Fort Cumberland were his wife and five children.[7] Just as some American Loyalists abandoned their wives, this bitter choice was faced by Patriots in Canada, and Allan felt it was necessary. The location of his family would soon prove a fateful choice.

Before the year was out, he would journey south to take his plea to Washington and Congress in person. Early in this trip, in October 1776, he had a chance encounter with Jonathan Eddy, a fellow Patriot and acquaintance who was in the process of plotting an attack on Fort Cumberland in support of American military operations. Allan tried to dissuade Eddy, who had an under-supplied force of only twenty-eight men, but his ambitious friend was determined. The attack took place in November 1776 and, as Allan predicted, it failed. The defeat demonstrated what might have been Allan’s more compelling reason for discouraging the attack in the first place – his wife and children were at the fort. They fled during the attack, according to his memoir, “without other clothing than what they happened to have on at the moment and hid themselves three days in the woods almost without food.”[8] Finally they found some potatoes baked in the smoldering ruins of their former home. Eventually they were rescued by his wife’s father, who escorted them to his residence. The home was soon surrounded by British soldiers demanding surrender of “the rebel’s wife.”

Mary was taken prisoner and transported to Halifax. The three younger children stayed with their grandfather;[9] the two oldest, William and Mark, apparently escaped. Mary was interrogated to determine her husband’s whereabouts. She volunteered no information, telling them only that “her husband had escaped to a free country.”[10] To taunt Mary, British soldiers’ wives would walk past her cell wearing her dresses, looted from her house before it burned down.[11] She was questioned for several months and imprisoned for approximately eight months. It is not known exactly when the family was reunited in Maine, but it was likely in 1778.[12]

While the Fort Cumberland attack was collapsing, Allan was still on his way to meet with Washington. He dined with the general on December 22, just three days before the Washington’s famous attack on Trenton. By early 1777 he was in Baltimore, testifying before the Second Continental Congress. Out of that session, he was appointed Superintendent of the Eastern Indians, a role in which he would excel, and issued a set of instructions from John Hancock.

In late January 1777 he started the journey back north, stopping in Boston for several months to work with Massachusetts authorities to arrange more support for his work in defending Maine. By June he was back in eastern Maine. His excellent relations with the local tribes prevented them from defecting to the British and tipping the precarious balance of power. With a combination of militia and native tribes, he was able to thwart a British amphibious assault in the Battle of Machias in August 1777, maintaining American control of the territory that is now eastern Maine.

It was an ongoing struggle to hold this territory. The British had the wherewithal to entice the Indians to their side, and eventually Allan’s promises of similar rewards started to wear thin. In 1780, he made plans to go to Boston to meet again with the Massachusetts government to ask for help. The Indians didn’t believe he would return. To demonstrate his commitment Allan agreed to a risky maneuver. He left his two oldest sons, William and Mark, thirteen and eleven years of age, with the tribes as hostages. His instructions to the boys included the following:

Let me entreat you my dear children to be careful of your company and manners, be moral, sober and discrete. The only observe your duty to the Almighty, morning and night. Mind strictly Sabbath day, not to have either work or play except necessity compels. I pray God to bless you my dear boys.[13]

True to his word, Allan returned. His sons had lived in tough conditions, “ragged, dirty and covered with vermin.”[14] Partly due to the trust their father had shown, the boys became great favorites with the Indians, and in later years “aided them in various ways.”[15] The tribes did not side with the British.

Allan’s actions as Superintendent, though not leading to the incorporation of Canada into the rebellion, smoothed relations with the tribes and he is generally credited with keeping Eastern Maine part of the United States, though the territory was disputed again in the War of 1812.[16] Maine remained part of Massachusetts until it seceded in 1820 and became the 23rd state.

Clement Gosselin

Clement Gosselin was a carpenter from Sainte-Famille, Île d’Orléans, Quebec, born in 1747. In his early twenties, he moved to Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière, acquired some land, and married his first wife. When American troops descended on Quebec in 1775, he immediately took to the cause. The reasons for his devotion to the rebellion are not well documented in the surviving literature, but he may have “joined the Americans out of rage, because they hated what the British had done to their homes and families during and after the conquest of 1759 [in the Seven Years War].”[17]

Getting French-Canadians to support the Patriot cause involved several complicating factors that weren’t part of Allan’s situation: religion (Catholicism), language (French), and the Quebec Act. The First Continental Congress attempted to surmount the first two by issuing a John Dickenson-penned “Letter to the Inhabitants of Quebec” in late 1774. To overcome the language barrier, this letter was translated into French. That was only half the battle, as the habitant (working class) population was overwhelmingly illiterate (estimated as high as ninety percent),[18] so the initial communication of the message depended on men higher up the social ladder (who tended to be less supportive of the rebellion). Beyond that it depended on word of mouth.

The more controversial area was the religion question, and here Congress was its own worst enemy. In the “Letter to the Inhabitants …” they downplayed the conflict between the Catholic religion in Quebec and the anti-Catholic sentiments that reigned throughout most of the thirteen colonies, noting that “the Swiss Cantons [are a] union composed of Roman Catholic and Protestant states.”[19] This was a stretch, made even worse by the fact that Congress also sent a message explaining itself to the British people (“Address to the People of Great Britain”), in which it articulated virulent anti-Catholic sentiments, expressing “astonishment that a British Parliament should ever consent to . . . a Religion that has deluged your Island in blood, and dispersed impiety, bigotry, persecution, murder, and rebellion, through every part of the world.”[20] Inevitably, the two documents were compared, and Congress was rightly distrusted for having been two-faced on the issue of religion.

Though the benefits they had been given under the Quebec Act may have had the effect of placating the French-Canadian population with religious toleration and establishment of French law in Quebec, their recent memories of the atrocities committed against them in the Seven Years War made this passivity fragile.[21] France’s entry into the Revolution, which occurred after Saratoga in 1777, only heightened British fears of an American invasion of Canada.[22]

Of the estimated 112,000 people in Canada in 1775, 80,000 were French-Canadians, thus any move on Canada would be unlikely to succeed without their involvement (the thirteen colonies at this time were home to an estimated 2.2 million people[23]). There are two sources, compiled for genealogical studies, listing the names of men who fought for the Patriot side in Canada; one lists approximately 630 French-Canadian participants,[24] while the other lists roughly 2,200 total participants.[25] The latter number includes Americans who moved to Canada as well as native-born Canadians.

Gosselin was an early Patriot and was likely among the approximately 200 Canadians who took part in the ill-fated New Year’s eve attack on Quebec led by Montgomery and Arnold.[26] When British relief forces broke up the subsequent siege of Quebec in May 1776, Gosselin retreated with the rest of the American and Canadian forces. He soon after went into hiding, emerging in August 1776. Still a wanted man, he was taken prisoner just two months later, and remained imprisoned until mid-1778.

Once released, he rejoined the forces of Canadian Moses Hazen in the United States. In November 1778, as one of Washington’s spies, he stole into Canada several times to get intelligence on the size of British forces. He also was severely wounded in the Siege of Yorktown. He remained in the American military until 1783, so he was in the Revolution nearly wire-to-wire.

Gosselin’s recruitment efforts for the Patriot cause did not escape notice in Canada. In a report following an investigation initiated by Provincial Gov. Sir Guy Carleton, he was identified as “among the most seditious and most cronies [sic] to the rebels.” The report also noted that “the said Sieur Clement Gosselin did not content himself with such conduct [recruiting for the rebels] only in this parish he traveled all the others up to 1s Pointe Levy, preaching the rebelion everywhere, exciting to plunder the small number of the zealous servants . . . at the gates of the churches and forced a few times the officers of the king to read the orders and proclamations of the rebels.”[27]

Due to his religion, Gosselin faced another threat that Allan did not – excommunication. One Sunday at Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatiere Church, the pastor singled him out from the pulpit:

Our Bishop is warning you, and other rebels like you, that you must cease your seditious and mutinous behavior at once! If you join the American effort to try to expel our British conquerors from this land, you will be excommunicated! If you are mortally wounded in combat, you will be denied the last rites of the Church. And you will not be buried in sacred ground! Your very soul is imperiled! And so are the souls of the men whom you are attempting to recruit! Give that serious thought, Clement Gosselin![28]

Despite the stern words, Gosselin was undeterred. Apparently, his wife and children were able to stay in Canada, as indicated by a letter he wrote to them there in October 1778, but not without hardships. In a letter to George Washington written on November 23, 1778 Gosselin, after detailing his spying activities and plans for another invasion attempt on Canada (which never materialized), begged for Washington’s help, saying, “all our possessions were seized and that our families were at the mercy of the world.”[29]

After the 1775-1776 siege of Quebec and the subsequent actions to drive Patriot forces out of Canada, Carleton assembled two task forces to root out sources of “rebel” support in the provinces and punish the perpetrators. The report of one of those groups, consisting of Francois Baby, Gabriel-Elzear Teschereau, and Jenkin Williams still exists. They systematically visited all the parishes, documenting what they learned, and firmly though leniently doling out punishment. According to Mark Anderson, there were “no arrests or floggings, no property seizures or home burnings.”[30] In most cases, rebels either had to declare loyalty to the crown or, if commissioned officers, burn their commissions. Allan and Gosselin had already left the country, having been punished by events.

Much as the British established a committee and a process to compensate exiled American Loyalists for their losses, the American Congress attempted to compensate those men who had done so much to support their cause in Canada. Like many of its constituents, Congress was land-rich and cash poor, so usually compensation was via land grants. On June 7, 1785, Congress created a committee to investigate the Canadian Patriot claims and resolved that commissioners “be directed to examine the accounts of such Canadian refugees, as have furnished the late armies of these states with any sort of supplies,” and report to Congress. The resolution was ordered published in Canada.[31]

Epilogue

Though later schemes were hatched to bring Canada into the conflict or even to re-invade, all either failed or were aborted. Despite the efforts of Patriots like Allan and Gosselin, the 1775 attack was the closest America ever came during this period to incorporating Canada during the Revolution. The Treaty of Paris of 1783 ceded the Ohio Territory to the United States, though negotiator Benjamin Franklin originally asked for all of Quebec.[32] Another takeover attempt was made in the war of 1812, but the effort crashed on the same rocks that almost wrecked the Revolution overall – lack of manpower, supplies, and hard currency with which to obtain the those two.

John Allan lost his Fort Cumberland home and property in the unsuccessful invasion of 1776. For his services and suffering he received two land grants, neither of which provided him much benefit – 22,000 acres from Massachusetts, rocky and barren land largely unusable, and 1,280 acres from Congress[33] in what is now part of Columbus, Ohio, too distant for him to visit. He ended up living in exile on an island in Lubec, Maine, and was a merchant for a time (allegedly doing some business with Benedict Arnold after the latter moved to Canada from exile in England). He and Mary had nine children (including George Washington Allan and Horatio Gates Allan). He died in Lubec on February 7, 1805, at the age of fifty-nine. Mary lived until 1819. On the island, formerly Allan’s Island, now Treat Island, a battery in his honor is erected near where he is buried. To this day, the descendants of the local native tribes hold him in high regard.

Clement Gosselin, eventually excommunicated from the Catholic church, lived in exile in Beekmantown, New York, near Lake Champlain, where Congress granted him 1,000 acres of property. He was also honored as an original member of The Society of the Cincinnati. He married two more times and had a total of ten children, half of whom were born after the Revolution. He died March 9, 1816, at the age of sixty-eight.

Allan and Gosselin suffered many of the same indignities suffered by American Loyalists: social ostracism – not detailed here, but likely occurred; physical danger; loss of property; bitter exile, though maybe not so bitter. Although both ended their lives outside their home country, both seemed reasonably pleased with their situation and were held in high regard by their neighbors and countrymen. The exile experiences of many American Loyalists definitely could be called “bitter.”[34] Though it is difficult to generalize based on the experiences of two individuals, this last part may be the major difference between the experiences of Canadian Patriots and American Loyalists. It is the difference between being on the winning and losing side.

[1]Gustave Lanctot, Canada and the American Revolution, Margaret M. Cameron, trans. (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1967), 39.

[2]George H. Allan, The Memoir of Colonel John Allan (Albany: Joel Munsell, 1867), 11.

[3]“A Citizen of Nova Scotia” to George Washington, February 3, 1776, Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-03-02-0192, accessed June 6, 2018.

[6]John Francis Sprague, “Colonel John Allan of American Revolutionary Fame,” Sprague’s Journal of Maine History, Volume II, No. 5 (February 1915), 234-5, files.usgwarchives.net/me/washington/machias/amerrev/allan/sj2p233.txt, accessed July 11, 2018.

[7]“John Allan,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Volume V (1801-1820), www.biographi.ca/en/bio/allan_john_5E.html, accessed June 11, 2018.

[8]Allan, The Memoir of Colonel John Allan, 14.

[12]“John Allan,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, 8.

[13]Allan, The Memoir of Colonel John Allan, 17.

[16]Anne Molloy, “Col. John Allan, A Hero for Maine,” Down East Magazine, July 1967, downeast.com/july-1967/, accessed July 2, 2018.

[17]“Clément Gosselin: Canadian Patriot and American Revolutionary,” lymcanada.org/clement-gosselin/, accessed June 26, 2018.

[18]Mark R. Anderson, The Battle for the Fourteenth Colony (Hanover and London: University Press of New England, 2013), 27

[19]“Continental Congress to the Inhabitants of the Province of Quebec, 26 Oct. 1774,” press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/v1ch14s12.html, accessed July 10, 2018.

[20]“Address to the People of Great Britain,“ amarch.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-amarch%3A97565, accessed July 10, 2018.

[21]Lanctot, Canada and the American Revolution, 54.

[23]Robert V. Wells, Population of the British Colonies in America Before 1776: A Survey of Census Data (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975), 284, table VII-5. The table represents estimates for 1775; the breakdown for Canada and the United States is as follows:

Newfoundland: 12,000

Nova Scotia: 20,000

Canada (Quebec): 80,000

Total: 112,500

Thirteen U.S. Colonies: 2,204,500

Total: 2,317,000

[24]Debbie Duay, Index to French-Canadian Revolutionary War Patriots, www.learnwebskills.com/Patriot/frenchcanadianPatriots.htm, accessed June 11, 2018.

[25]Virginia Easley DeMarce, Canadian Participants in the American Revolution – An Index (Compiled for publication in “Lost in Canada”), 1980,dcms.lds.org/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE13546789, accessed June 27, 2018.

[26]“Clement Gosselin,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Volume V – 1801-1820, www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gosselin_clement_5E.html, accessed June 27, 2018.

[27]“L.-Amable Proulx, Printer of his Majesty the King,”Report Archivist of the province of Quebec for 1927-1928,1928, 496. This book, in French, included the Baby/Tecschereau/Williams report to Carleton. This author translated these sections from French to English using Google Translate.

[28]Document attached to the Gosselin Family Tree at www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/tree/47533010/person/24653272095/media/39adb7a7-4799-4784-9eaf-663afe13f424?_phsrc=awH3&_phstart=successSource, accessed June 29, 2018.

[29]Jacob Bayley to Washington, November 23, 1778, Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-18-02-0270, accessed July 5, 2018. The Gosselin letter, in French, was an attachment to the Bayley letter. Translated from French to English via Google Translate.

[30]Anderson, The Battle for the Fourteenth Colony, 342.

[31]Carl Wittke, “Canadian Refugees in the American Revolution,” www.electriccanadian.com/history/articles/refugees.htm, accessed June 5, 2018.

[32]National Constitution Center, constitutioncenter.org/blog/when-canada-was-invited-to-join-the-united-states, accessed July 12, 2018.

[33]Walter Lowrie, Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United States, Volume 1 (Washington, DC: Duff Green, 1834), 99. This document has some conflicts within; two pages prior it awards 1,000 acres to Allan. There was no mention of Gosselin as his case was handled separately.

[33]See Patriots Turned Loyalist – The Experiences of Joseph Galloway and Isaac Lowand Grace Galloway – Abandoned Loyalist Wife.

9 Comments

What of the possibility Allan may have been the one to divulge Washington’s plans to cross the Delaware River and attack Trenton in December 1776? There is an intriguing question about his December 22 visit with GW and the timing of the secret information being supplied to the British. Puts his after-war dealings with Arnold also in a different light.

Clement Gosselin was my 4th great-grandfather in my mother’s side. Though he served in the Second Canadian Regiment under Hazen, he also fought in Lafayette’s regiment in Virginia at the Battle of Green Springs and at the siege of Yorktown, where he was wounded in the leg. He served most of his military career as a captain, being promoted to brevet major at the time of his discharged in 1783. He was also part of the fake attempt to make the British in Canada think another invasion was imminent when he and Hazen’s men helped hack out of the wilderness a road through what is now northern Vermont. The plan kept valuable British troops bottled up above the 45th parallel for months.

Clement Gosselin was my 4th great-grandfather on my mother’s side. Though he served in the Second Canadian Regiment under Hazen, he also fought in Lafayette’s regiment in Virginia at the Battle of Green Springs and at the siege of Yorktown, where he was wounded in the leg. He served most of his military career as a captain, being promoted to brevet major at the time of his discharge in 1783. He was also part of the fake attempt to make the British in Canada think another invasion was imminent when he and Hazen’s men helped hack out of the wilderness a road through what is now northern Vermont. The plan kept valuable British troops bottled up above the 45th parallel for months.

This is a fine article—but when are US historians going to stop using biased language in describing those who fought in the war?

Historians have fallen into easy, but sloppy, descriptions.

To call Washington and those on his side “patriots” is prejudicial language that, frankly, plays only to the winners. Historians should rise above mob.

I prefer the term “rebels,” because factually, they were rebelling against Britain. They themselves often referred to their fellow rebels as “whigs.” Or, you can call them anti-Monarchists, or revolutionaries. Just don’t call them patriots.

The loyalists were just as patriotic as the rebels, as were Native Americans, the vast majority of whom opposed the rebels.

Historians should use neutral language unless they’re quoting someone.

You are absolutely correct, Don. It was an unlawful rising and taking up of arms against a legal government at the head of the world’s most powerful nation. There is no legitimate way to call them anything other than rebels and to term them as “patriots” immediately demonizes the British. It then commands the tone of the conversation as being good against evil and hinders meaningful discussion about the underlying dispute.

No, they were not patriots, patriots don’t unilaterally take up arms when not they were not physically threatened and head a rebellion against established law. We call them what they are, “separatists” or “rebels,” or, as you suggest, “anti-Monarchists or revolutionaries” and that way we identify the conflict in more meaningful ways that does not prejudge.

I think the growing interest in the American Revolution outside the 13 mainland colonies that would become the United States is very important scholarship. I also appreciate the interest beyond “the Loyalists” of the North.

I think Don’s comment is spot on. Furthermore, there is a very long and contested historiography about the Revolution in what would become Canada, especially in the Atlantic region. Some of the most recent studies demonstrate that questions of “loyalty” are particularly tricky in Nova Scotia. As I believe Jerry Bannister and Liam Riordan correctly argue, loyalism was complex and amorphous ideology that spanned the British Atlantic; certainly “patriotism,” if there was such a thing, was equally heterogenous.

I’d also quibble with the authors take on the indigenous people of Atlantic Canada. Although Le Grand Dérangement was a horrific experience for Acadians and Indigenous people, it was largely an incomplete and ineffective policy on the part of the British. The Indigenous-Acadian alliance continued to dictate power relationships in Nova Scotia, which included modern New Brunswick and disputed parts of Maine, into the early 19th Century. While contemporaries may have seen Allan as instrumental in handling native affairs, The First Nations Mi’kmaq people, and a number of other distinct nations, acted in their best interests regardless of the “allegiances” Europeans may have perceived. In his dealings with Indigenous peoples, perhaps Allan was responding to First Nations’ pressures more than directions from white politicians.

Last, I’m particularly interested in the case of Allan’s wife. Do these stories come from her writings? It seems from you footnote that these are drawn from Allan’s memoir. To what extent might these stories have been exaggerated as anti-British propaganda? Do you have any idea where in Halifax she was detained?

I concur. I use the same language, avoiding the word “patriots”. A patriot is a lover of one’s country. The British thought they were patriots too, trying to hold the Empire together.

It’s always good to see work on the American Revolution focused on regions outside the rebellious thirteen mainland colonies that would become the United States. I’m particularly interested in story of Allan’s wife. Do you have an idea of exactly where she was “held/imprisoned” in Halifax? Do we know which women were doing the taunting? Do any of her writings survive?

As to Don’s comment, I think it’s also imperative for American historians to be more cognizant of Canadian historiography. In the case of the Allan narrative, there are a number of wonderfully rich histories of the American Revolution in Atlantic Canada that deal with issues of “rebellion” and “loyalty” and question if those terms work at all.

I’d most like to quibble with the author’s depiction of Indigenous people. For many Natives of the greater American Northeast, the War of Independence was but another in a series of European battles dating back to the late seventeenth century. Particularly in Nova Scotia, which included what is today New Brunswick and even disputed regions of what is now Maine, the First Nations Mi’kmaw people, alongside a number of other local nations, continued to dictate economic and political relations through the early nineteenth century. Le Grand Dérangement of the mid-eighteenth century was largely unsuccessful in reorienting power, and with the exception of maybe the greater Halifax region, Indigenous people and remaining Acadians continued to dominate the region at the time of the American rebellion. Allan was certainly influential in his correspondence with these powers. Indigenous support, however, came from a perspective that Allan did not comprehend. Mi’kmaw leaders supported sides that played to their best interests without any consideration to questions of “patriotism” or “loyalty.” Regardless of “allegiances,” following the war native people on both sides of the new border found themselves increasingly disposed of traditional lands by a people a people they understood to be a homogenous enemy, regardless of British-Canadian or American citizenship.

Interesting discussion.

Were they really “rebels” or “separatists”, though? I would argue that at first the colonists were simply trying to _preserve their traditional constitutional rights as British subjects._

Look as far back as 1761– “when the child independence was born”–the Writs of Assistance should’ve been considered illegal under British constitutional law, look at the Massachusetts Government Act which dismantled the original Mass. charter. Look at the Crown paying the salaries of colonial judges, rather than those salaries being paid by local assemblies. The colonists felt their “historical constitutional rights* were being abrogated. I’d argue that they weren’t “rebelling” or trying to “separate” or be “anti-monarchs” at all, at first.

I don’t think use of any of the words “Whig” “Tory” “Loyalist” “Patriot” indicates bias on the part of the historian. All of these words were used contemporaneously. They’re the labels we affix to large groups of people. I guess it’s a simpler way to refer to the vagaries of political thought amongst a huge population, but sloppy, no.

As for writing history using only neutral language…. I don’t see any value in that. Also, I’d argue that’s not possible firstly because _all_ words have connotation. Secondly, all history is an interpretation. We view the past through a prism, just as contemporaries understood their experiences through their own prism… Therefore, I’d ask, what or who could possibly be neutral? As a historian, my goals are utter accuracy, total thoroughness, as much context as possible… but not neutrality.