George Washington realized early in the Revolutionary War that the British Navy provided the King’s army with an advantage in mobility. Not long after taking command of the fledgling army around Boston, Washington took steps to provide his forces with a maritime arm of its own.

Several states had organized navies of their own as soon as hostilities opened and initially Washington tried to take advantage of these ships. Desperately short on weapons and ammunition, Washington wrote to Governor Nicholas Cooke of Rhode Island: “Bermuda, where there is a very considerable Magazine of Powder in a remote Part of the Island, & the Inhabitants well disposed not only to our Cause in General, but to assist in this Enterprize in particular . . . We understand there are two armed Vessels in your Province commanded by Men of known Activity & Spirit: One of which it is proposed to dispatch on this Errand with such other Assistance as may be requisite.”[1] Understanding the difficulty of the mission, Washington suggested: “Should it be inconvenient to part with one of the armed Vessels perhaps some other might be fitted out or you could devise some other Mode of executing this Plan, so that in Case of a Disappointmt the Vessel might proceed to some other Island to purchase.”[2] Although the governor did send a vessel to Bermuda, ships from Pennsylvania and South Carolina had already taken the powder.

The Continental Congress would first address the issue of creating a navy by addressing a resolution for the creation of a fleet on October 3, 1775. The resolution was tabled, but eventually passed on October 13. George Washington did not wait for Congress to act, creating his own flotilla.

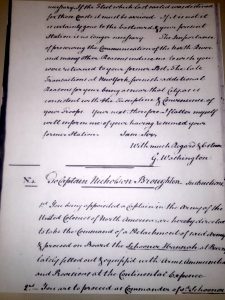

On September 2, 1775, Washington sent a letter to Capt. Nicholson Broughton, a captain in John Glover’s Massachusetts Regiment, authorizing him to take command of the first vessel in the Continental service: “You being appointed a Captain in the Army of the United Colonies of North America, are hereby direct[ed] to take the Command of a Detachment of sd Army & proceed on Board the Schooner Hannah at Beverly lately fitted out & equipp’d with Arms Ammunition & Proviss. at the Continental Expence.”[3] Washington gave Broughton a list of missions to undertake as well as particulars as to how to organize the first ship in Continental service.

Broughton set sail on September 5 and returned two days later with the first prize of the fledgling naval service. Encouraged by the success and aware of increased British naval activity, Washington authorized an expansion of the fleet, informing Congress on October 5, 1775: “I have directed 3 Vessels to be equipped in order to cut off the Supplies, & from the Number of Vessels hourly arriving it may become an Object of some Importance.”[4] The ships of Washington’s fleet, as well as ships authorized by the states had enough success for further expansion. Washington informed Richard Henry Lee: “At the Continental expence I have fitted out Six pr the Inclosed list, two of which are upon the Cruize, directed by the Congress—the rest ply about Capes Cod & Ann—as yet to very little purpose.”[5]

The six vessels were the schooners Lee, Harrison, Lynch, Franklin, and Warren, and the brigantine Washington. Tradition has it that the fleet flew the “Appeal to Heaven” flag, as suggested by Col. Joseph Reed: “Please to fix upon some particular colour for a flag, and a signal by which our vessels may know one another. What do you think of a flag with a white ground, a tree in the middle, the motto ‘Appeal to Heaven?’ This is the flag of our floating batteries.”[6]

Capt. John Manley commanding the Lee made the most impressive capture on November 29, 1775. His prize was the British brigantine Nancy, carrying two thousand muskets, thirty tons of musket shot, one hundred thousand flints, thirty thousand round shot, barrels of powder, and a thirteen-inch mortar.

Just as the organization and formation of the motley army was a trial for Washington, the fleet also tried his patience due to similar problems of logistics:

. . . by the Last Accounts from the Armed Schooners Sent to the River St Lawrence, I fear we have but little to expect from them, they were falling Short of provision, & mention that they woud be obliged to return, which at this time is particularly unfortunate, as if they chose a proper Station, all the vessells Comeing down that river must fall into their hands—the plague trouble & vexation I have had with the Crews of all the armed vessells, is inexpressable, I do believe there is not on earth, a more disorderly Set, every time they Come into port, we hear of Nothing but mutinous Complaints, Manlys Success has Lately, & but Lately quieted his people[.] the Crews of the Washington & Harrison have Actually deserted them, So that I have been under the necessity of ordering the Agent to Lay the Later up, & get hands for the other on the best terms he Could.[7]

William Watson, Washington’s agent in obtaining naval supplies, wrote that provisioning the ships along with Manley’s success had a positive effect on the unruly sailors. “After repairing aboard the brig [Washington] Saturday night, inquiring into the cause of the uneasiness among the people and finding it principally owing to their want of clothing, and after supplying them with what they wanted, the whole crew, to a man, gave three cheers, and declared their readiness to go to sea the next morning. The warm weather at the time and the news of Captain Manly’s good success, had a very happy influence on the minds of the people.”[8] Washington was so impressed with the 42-year-old Manley that he gave him command of the little fleet on January 1, 1776.

Manley repeated his success a few days after his appointment as commodore. Manley’s Lee captured the British ships Happy Return and Norfolk off Nantasket and brought the prizes in despite attempts by the gunboat General Gage to intervene. Washington wrote Manley: “I received your agreeable Letter of the 26th instant giveing an account of your haveing taken & Carried into Plymouth two of the Enemys transports. Your Conduct in engageing the eight Gun Schooner, with So few hands as you went out with, your attention in Secureing Your prizes, & your general good behavior since you first engaged in the Service, merits mine & your Countrys thanks.”[9]

Estimates vary but Washington’s navy may have including eleven different ships, which throughout the course of the war captured around 55 British vessels. Although Washington’s little ships and those of the various state navies did achieve some victories, they could never hope to defeat the might of the most powerful navy in the world and thus served only as thorns in the Royal Navy’s side. Their biggest value was obtaining supplies for the American cause.

The arena of battle moved to New York when the British fleet left Boston Harbor on June 14, 1776. Combined with Congress’ new naval establishment, this led to the disbanding of Washington’s Navy in early 1777 by the Marine Committee of Congress. The little ships were sold or delivered back to their owners. Some became privateers and continued their harassment of the British.

Nicholson Broughton resigned from Continental service after capturing neutral Canadians, resulting in a reprimand from Washington. He served briefly in the army, eventually returning to the sea as a privateer. Captured by the British, he was imprisoned in England, returning to Massachusetts after his release. John Manley remained in Continental service and was also captured by the British in New York but released on exchange. He became a privateer but was captured again and sent to prison in England. Released from captivity, Manley finished the war as a Continental captain.

The Maritime Committee of Congress served as the governing body of the Continental Navy for the rest of the war. Although George Washington concentrated on leading the army, he acknowledged the importance of a fleet, urging the French to send their own navy to assist. His cooperation with the French fleet led to the victory at Yorktown. As he told Lafayette at the time:

It follows then as certain as that night succeeds the day, that with out a Decisive Naval force we can do nothing definitive. and with it every thing honourable and glorious. A constant Naval superiority [would terminate] the War speedily—without it, I do not know that it will ever be terminated honourably.[10]

A few years later, George Washington signed an “Act to Provide a Naval Armament” passed by Congress on March 10, 1794. It was the beginning of the United States Navy,[11] calling for the construction of six frigates. Among those ships was the U.S.S. Constitution, still in service today and a tangible link to the founder of both the Continental Navy and the United States Navy, George Washington.

[1]George Washington to Nicholas Cooke, August 4, 1775. Philander D. Chase, ed. The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, Vol. 1, June-September 1775 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1985), 221.

[3]Ibid, 398 (emphasis added).

[4]George Washington to John Hancock, October 5, 1775. Philander D. Chase, ed. The Papers of George Washington, vol. 2, September –December 1775 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1987), 100.

[5]Washington to Lee November 27, 1775, Ibid, 435.

[6]Peter Force. American Archives, Fourth Series, containing a Documentary History of the English Colonies in North America from the King’s Message to Parliament of March 7, 1774, to The Declaration of Independence of the United States, Volume III (Washington: M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, 1840), 1126.

[7]Washington to John Hancock, December 4, 1775, Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 2, 484.

[8]Watson to Stephen Moylan, December 4, 1775. Henry E. Waite. Extracts Relating to the Origin of the American Navy (Boston: The New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1890), 21.

[9]Washington to Manley, January 28, 1776. Philander D. Chase, ed. The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 3, January- March 1776 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1988), 206.

[10]John C. Fitzpatrick, ed. The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, Volume 23, August 16, 1781-February 15, 1782 (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1937), 341.

[11]The U.S. Navy today celebrates its birth as October 13, 1775, the day the Continental Navy was authorized.

4 Comments

This is a fine introduction, Mr. Dacas. Yet you may agree it is easy to ascribe to George Washington the idea of creating a navy, while many members of Congress and colonial legislatures owned businesses that relied on shipping. It would be fair to suggest that others at the time had similar thoughts. One might say that opposition to the confiscation of John Hancock’s ship, Liberty, in 1767, or the burning of the Gaspee in 1772, were fledgling attempts to use a makeshift navy against the British.

I thought the picture of Hannah looked familiar! I served on Glover (AGFF-1 and later FF-1098) from August 1977 (when I completed Naval Gun School at Great Lakes) until December 1980; pretty sure I saw it in the wardroom…Thanks for the memories!

Dear Jeff: Do you know the name of the captain of the British brigantine Nancy that John Manley took captive? Was he tried by an Admiralty Court for giving up his ship as he was approaching Boston?

The Nancy store ship was not a Royal Navy warship, but – like all transports used by the Royal Navy in this era – a private vessel operating under contract to the navy. The master was named Robert Hunter, and the contractor John Wilkinson. There is no evidence that the master (who was a civilian, not a navy officer) was brought to trial for giving up his unarmed transport. At this early stage of the conflict, when it wasn’t at all clear that it was an all-out war to be waged at sea as well as on land, the Royal Navy sent transports to America unescorted; by early 1776, when the scope and hazards were clearer, transports were sent in convoys with Royal Navy escorts.

You can read more about the Nancy’s capture in Vol. 3 of Naval Documents of the American Revolution.