In a quiet Baptist cemetery in Hilltown Township, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, repose the remains of Isaac Lewis. Lewis served under Gen. George Washington during the prelude to a critical battle of the American Revolution, one which kept open the path to American Independence. Lewis’s battle experience was brief but memorable.

Isaac, son of Henry and Margaret Lewis, was born on August 1, 1751 on Hilltown property acquired before 1729 by Isaac’s grandfather Morris Lewis. Morris had emigrated from Wales about 1717 with his wife, three children and a brother Henry. The latter was reported to have been in trouble with the British government over a political offense which might have cost him his life had he remained in Wales. Morris’s son Henry Lewis, born in Wales in 1716, continued to live on family farmlands, and became a major landowner in New Britain, Pennsylvania, where he constructed a tavern that operated during the Revolutionary years.[1] Henry’s son Isaac married Mary Jones, a neighbor, and the couple’s first child, daughter Rachel, arrived in 1775. Shortly after the Declaration of Independence was adopted in July 1776, Isaac at age twenty-four left wife, child, and family farm behind to go to war against the British, enlisting in a Berks County unit of Pennsylvania’s “Flying Camp.”

Formation of the Flying Camp

The Flying Camp was the brainchild of General Washington, based upon the precedent of the French Camp Volant: “a strong body of horse or foot … always in motion to cover its own garrisons, and to keep the enemy’s army in a continual alarm.”[2] By the Spring of 1776, the Revolution’s battlefield had shifted from Boston. General Washington had to prepare to defend New Jersey and other middle Atlantic colonies, in particular areas surrounding New York City, from British attacks. The existing Continental Army was unequal to the task: it was limited by its small size, loose discipline, short enlistments, and the reluctance of its soldiers to serve far from their homes. Washington found the need compelling for a mobile military force, a “Flying Camp” whose forces would be drawn primarily from militias in Delaware, Maryland, and Pennsylvania.[3] Washington’s proposal for the Flying Camp was approved by Congress on June 3, 1776. Hugh Mercer was made its brigadier general, and its headquarters were established at Amboy (today’s Perth Amboy), New Jersey. Of the 10,000-soldier quota established for the Flying Camp, Pennsylvania was assigned the lion’s share, 6,000 troops. The Bucks County Associators (militia) were asked to provide 400 men, while the nearby Berks County Associators were assigned a larger 666-man quota. It was determined that existing Pennsylvania companies would be sent to the Flying Camp headquarters at Amboy, to remain there until new Flying Camp units could relieve them.[4]

On July 2, 1776, a meeting was held at the Reading Courthouse to select officers for a Berks County battalion of the Flying Camp. Henry Haller, a well-known local tailor and tavern keeper, was made colonel; Nicholas Lotz (often recorded as “Lutz”) was chosen lieutenant colonel. After some early confusion, several Flying Camp units were raised. The same month, Isaac Lewis appeared in Reading to enlist for nine months in the Berks Battalion. He enrolled as a private in Capt. John Ludwig’s company, under Colonel Haller’s command.[5]

Why Lewis left his family farmlands in Hilltown to join the Berks County battalion rather than Col. Joseph Hart’s Bucks County Flying Camp Battalion remains unknown. Perhaps the Bucks battalion had filled its quota and had no more room. Or perhaps it was because Berks County had been particularly aggressive in its resistance to perceived British tyranny. From the passage of the Stamp Act through the Boston Tea Party, Berks County colonists had been highly sympathetic to the Patriot cause. By June 1775, events such as the Battle of Bunker Hill had moved Berks residents to answer a call by the Continental Congress for expert riflemen, and Berks County had sent a company captained by George Nagel to Cambridge, Massachusetts. A Berks County unit captained by Jonathan Jones had in early 1776 participated in a campaign for the conquest of Quebec, and then accompanied Patriot forces in a retreat to Fort Ticonderoga. Still other Berks County military units had been formed before the advent of the Flying Camp.[6]

The troops recruited for the Flying Camp were promised a bonus for volunteering,[7] but were poorly paid and poorly provisioned. Congress required that they “come provided with arms, accoutrements and camp kettles.”[8] Their actual weapons were a motley assortment of fowling-pieces, rifles, good English muskets, and locally-made copies; many of the weapons were not equipped with bayonets. Flying Camp members were not even provided with military uniforms. By late July 1776, General Washington, who earlier had hoped to equip all his troops with proper uniforms, recommending “the adoption of hunting shirts and breeches as a cheap and convenient dress, and as one which might have its terrors for the enemy.” It was thought that the enemy would imagine “that every rebel so dressed was a ‘complete marksman.’”[9] By mid-September some regiments in the Flying Camp had adopted this uniform,[10] but their clothing in July and August is not recorded.

The Road to Long Island

Isaac Lewis’ company was ordered to New Jersey in late July 1776, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Lotz. Colonel Haller himself remained behind in Reading to complete the formation of the Berks Flying Camp Battalion through the addition of other companies which had not reached full strength.[11] No contemporary record of Isaac Lewis’s company’s march to New Jersey has been found. However, it is recorded that another Berks County unit under the command of Col. John Patton took from August 9 to August 22, 1776 to march from a camp at the town of Womelsdorf in Berks County to the Flying Camp headquarters at Perth Amboy. Colonel Patton’s unit proceeded to Reading (five miles), to and through Kutztown (eighteen miles), Bethlehem (twenty-four miles), Straw’s Tavern (fifteen miles), the South Branch of the Raritan River (twenty miles), “Punch Bowl” (twenty miles), Bonhamtown (seventeen miles), and finally to Perth Amboy (seven miles).[12]

Whenever Lewis’s unit began and ended its march to the Amboy camp, before August 20, 1776, the Berks County Flying Camp troops sent ahead under Lieutenant Colonel Lotz had left New Jersey and were headed toward Long Island,[13] by way of New York City. When a different Berks militia company under the command of Col. Joseph Hiester arrived at Elizabeth, New Jersey, the troops encountered Gen. William Alexander, Lord Stirling, who informed them that Washington was preparing to oppose an imminent attack on New York City. It is said that the “sudden appearance of danger and call to immediate active service” came with too little warning for Hiester’s militiamen, who had in their minds enlisted to defend their own homes. Some initially refused to obey the order to march to New York, thinking that it was “unreasonable to ask them to go further.” Colonel Hiester reportedly had to plead with his men to go forward and in the end was successful in doing so.[14]But there is no indication that Lieutenant Colonel Lutz ever had to plead with his Berks Flying Camp enlistees to do their duty.

The challenge to be faced by the Flying Camp at the end of its march to Long Island was formidable. A substantial British fleet had entered New York Bay on June 29. Additional British ships from the Mediterranean, the West Indies and the Florida coast soon joined them, and by August 21, the New York Bay contained an intimidating fleet of thirty-five warships and 400 transports, carrying about 35,000 men, an armada that undoubtedly represented the largest invading force ever seen in the Western Hemisphere.[15]

General Washington’s total American forces at the time totaled less than 20,000—4,000 of which were unfit for duty. Less than 6,000 had even a year’s experience. Unlike the well-trained British and German soldiers facing them, Washington’s army was comprised mostly of raw recruits from offices, shops, and farms. The Americans initially may have assembled less than 5,000 troops on Long Island because Washington, mistakenly believing that only 8,000 British troops would reach the island, kept the bulk of his forces in reserve in New York City.[16]

The newly-enlisted, untrained Flying Camp troops were not only headed toward a daunting mismatch of forces, but the terrors facing them on the eve of battle were compounded by unusually frightening weather. On August 21, an ominous electrical storm crashed over New York City. The storm was “as vicious as any in living memory, and for those who saw omens in such unleashed fury from the elements … a night so violent seemed filled with portent.” The storm continued three hours and “lightning fell in masses and sheets of fire to the earth, and seemed to strike incessantly and on every side.” Ten soldiers encamped by the East River were killed in one flash; soldier hurrying through the city streets was struck deaf, blind and mute. Elsewhere three officers were killed by a single lightning bolt, with bodies roasted black and the tips of their swords and coins in their pockets melted.[17]

The Landing of British Forces

After the storm of the preceding night, August 22, 1776 dawned clear and hot. During the course of the morning, the British army transferred some 15,000 men, replete with guns and baggage, from Staten Island to Long Island.[18] General Washington remained unaware of the extent of the British movement. Fearing that they were reserving many of their troops to attack either at New York City or elsewhere, he ordered only a limited number of reinforcements, perhaps 1,500 men, to cross from New York City to Long Island to reinforce a unit of some 550 Pennsylvania riflemen, under the command of the veteran Col. Edward Hand, at the time the only Patriot force stationed near the British landing site.[19] Among the reinforcements ordered to cross were the men in Lieutenant Colonel Lotz’s command, including Isaac Lewis. It has been aptly written that considering the disparity of forces, those troops when ferried across the East River from New York to Brooklyn performed an act “almost equivalent to voluntary martyrdom.”[20]

Soon after the debarkation of British troops on August 22, Lotz’s men, including Isaac Lewis, had reached Long Island and had taken a position on hills overlooking Flatbush near Colonel Hand’s Pennsylvania riflemen.[21] The American forces watched the British landings, but made no serious attempt to prevent them, since there were simply too many potential landing points to make such an effort feasible.

A letter from American Col. William Douglas to his wife from New York dated August 23, 1776, recorded that “The Enemy landed yesterday on Long Island at Gravesend, about nine miles from our lines; our flying parties are annoying them all the while.” [22] That may have been a bit of an overstatement: other reports state that Colonel Hand’s forces sniped at the British troops after the landing, only to find themselves pursued by Hessian grenadiers and jaegers and Scottish highlanders.[23] Still other reports declare that when, following the British landing, British troops moved to occupy the village of Flatbush (Brooklyn), Colonel Hand’s men marched alongside part of the way, but avoided an open fight with the numerically superior enemy, and then began burning grain and stacks of hay, as well as killing cattle.[24]

The reason for this destruction of crops and animals was elemental. The British troops were greatly impressed by the rich farmland they found in America and eyed the abundant ripe apples, peaches and other crops of Long Island. Moreover, upon the landing of the British forces, hundreds of Long Island Loyalists had converged upon them to welcome them with open arms, some bestowing upon them gifts of “long-hidden supplies of all kinds.”[25]The Patriot defenders sought to prevent the invaders from further feasting upon the rich bounty of the Long Island orchards, fields and farms. Under military orders, the grain and hay of neighboring farmers had either been stacked in the field or so far removed from the barns that the burning of the forage would not endanger nearby buildings. The landing of the British became the signal to commence the burning of crops, resulting in “a conflagration that spread over the wide plains of the five towns of Kings County,” a conflagration “devouring the rich harvests” and “covering the land with a dense canopy of smoke, or lighting up the gloomy night with lurid flames.”[26]

Order to Isaac Lewis and the Consequences

Undaunted by the frightening spectacle unfolding before him on August 22, and following the example of Colonel Hand, Lieutenant Colonel Lotz “ordered out Isaac Lewis one of the Soldiers in Captn. John Ludwig’s Company … with a number of others under the Command of Captn. Mouser [Mauser] of the Same Regiment to burn some Stacks of Grain near Flat Bush where there then was a british Guard.” Lewis and his fellow soldiers obediently “effected [the order] within [Lt. Col. Lotz’s] View & drove away the said Guard after a short Skirmish.” But in this early skirmish Lewis was “wounded by a Bullet shot thro’ his right Thigh.” Lieutenant Colonel Lotz would later certify that the wound, by “contracting the sinews of” Lewis’s right thigh and leg, rendered them “considerably shorter than his left Thigh & Leg so as to oblige him to tread the Ground only with the Toes of his right Foot and has disabled him from serving in the Army or getting his Livelihood as he used to do.” [27]Isaac Lewis was likely the first casualty in what would be one of the Continental Army’s most difficult campaigns.

Lewis’s crippling injury almost certainly saved his life. The most vicious fighting at Long Island would begin days later, after an infusion of additional British troops swelled their numbers on Long Island to over 20,000. About midnight on August 27, 1776, Lieutenant Colonel Lotz’s Berks County Flying Camp Battalion was positioned south of the Gowanus Bay, near the water. In the darkness of night, British troops surprised and drove back pickets at the western flank of the American advanced line.[28] Lieutenant Colonel Lotz and his troops were among the units ordered out to support the pickets and saw heavy fighting.[29] A near rout of the Americans followed, and only a valiant rear guard action by a Patriot force that included Lieutenant Colonel Lotz’s troops enabled the rest of the army to reach the protection of fortifications which the American Army had erected at Gowanus Cove. In the course of the fighting, Hessians who attacked the Berks troops were extremely brutal, thrusting bayonets through the wounded and refusing to spare their lives. Lieutenant Colonel Lotz’s men were badly mauled, and Lotz himself was taken prisoner, as were other officers of Haller’s Berks Flying Camp Battalion, including Captains Joseph Hiester and Jacob Mauser. By the morning of August 28, the American forces literally had their backs to the East River. Fortunately for the greatly-outnumbered American troops, no further attack came. That afternoon rain fell, in the form of a cold and dreary downpour.[30] Beginning at about 9 P.M. on August 29 and continuing into the early morning hours of August 30, General Washington avoided possible annihilation of his forces— preserving the cause of American Independence—by a surprise tactic. Recruiting boats from sympathetic locals, he evacuated his forces to Manhattan under the cover of darkness and fog.

During the Battle of Long Island, American forces fought forces possibly four times their number. Afterwards many Patriot soldiers lay dead, some slain in cold blood, some pinned by bayonets to trees. Over a thousand Americans were taken prisoner. Many of these would later suffer mightily in British prisons. Isaac Lewis by virtue of his early wounding escaped death and capture.

After Washington’s crossing to Manhattan, the disabled Isaac Lewis no longer saw combat, and was hospitalized at several locations. Most likely, he was first moved to a barracks in Manhattan – “a dreadful scene of confusion and disorder” – then, as Washington’s army retreated southward through New Jersey, to Newark, then to other temporary “hospitals” in private homes, barns, churches, or schoolhouses across New Jersey, in efforts to evade the ever-pursuing British. Temporary hospitals for Washington’s army were at times established at Elizabeth, Brunswick, Trenton, Morristown, Amboy, and Fort Lee in New Jersey, as well as at Philadelphia and Bethlehem in Pennsylvania.[31]

Lewis was released from service at Reading, Pennsylvania, the following spring, and was taken home to Hilltown Township by friends. He later sired a second child, son Henry, born in 1781. Lewis became a shoemaker, and spent the remainder of his days hobbling with a crutch about the byways of Hilltown Township.[32]

Isaac Lewis’s Pension

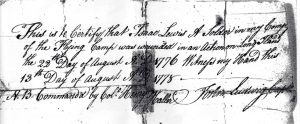

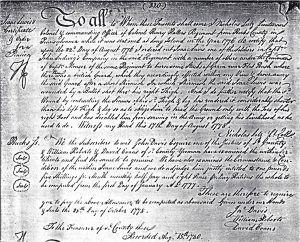

On August 13, 1778 Capt. John Ludwig executed a document attesting that Lewis had been wounded in an action on Long Island, and four days later Lt. Col. Nicholas Lotz (paroled by the British in April 1778) issued the more expansive certification of the circumstances and nature of Lewis’s wounding quoted above. With his claim for a pension supported by these documents, Lewis was placed on the military pension rolls on March 4, 1789,[33] and for many years collected his monthly pension without incident.

A new pension law was passed in 1818. On September 6, 1819, Lewis made application for this new pension at an alderman’s office in Philadelphia where he had been accustomed to renewing his original pension. This time, he was required to bring evidence of his service and a new certificate, because the 1818 Act of Congress applied to men who had served in the “Continental establishment.” Before Bucks County Judge William Watts, Lewis recited the circumstances of his service and disability, stating that he believed he had been wounded while serving as part of the “continental establishment.” Judge Watts certified Lewis’s service and need for assistance, but forwarded the file to Washington for a determination of whether Lewis’s service with the Flying Camp was eligible for the increased benefits. The judge stated that Lewis was “not very intelligent he does not know whether his pension has been from the U. States or State of Penna” and could not recall which bank he had used to cash his pension check.[34] In 1819, Lewis was denied increased benefits on the grounds that the Flying Camp was not part of the regular army or Continental establishment, but he continued to receive his regular pension. In all, he collected a total of $1,302.73 in pension benefits during his lifetime.[35]

According to local historian Edward Mathews, Isaac Lewis died a “poor man” at age seventy on September 21, 1821, with an inventory valued at just $176.71 1/2. His personal property was sparse, consisting of little more than wearing apparel (including a hat and handkerchief), case and table; bed and bedding; coverlet; a knife; spectacles; two books; some accounts, notes and pension due and corn in the ground.[36]

Isaac Lewis’s Legacy

Most likely because of the losses to Lieutenant Colonel Lotz’s Flying Camp unit at Long Island, Isaac Lewis’ military record has long been lost to history, and only his pension file remains to evidence his service. Nonetheless, Lewis has not been completely forgotten by history, though his tale has to date been preserved only briefly and with some embellishments or distortions. A Bucks County historian wrote that Lewis, “a soldier of the Revolution, was shot through the leg on Long Island while setting fire to some wheat-stacks that had fallen into possession of the British, and his comrades rescued him with great difficulty. He was with the army at Valley Forge, and from there was sent to Reading, probably as an invalid, whence he was brought home by his parents.”[37] Historian Mathews, in the Doylestown Intelligencer of May 24, 1906, declared that Lewis was wounded by a musket ball through the leg, “while setting fire to some stacks of wheat of which the British had taken possession.” “Badly wounded,” according to Mathews, Lewis “lay in a forlorn condition,” and it “was with some difficulty that he attracted attention of his comrades, who finally rescued him.” Mathews stated that Lewis was removed to Valley Forge, then to Reading, from which a letter was sent to his parents, “who came and took him home.” Mathews added that Lewis was a “very large, stout man … always crippled after recovering from his wound.”

Lewis’s application for an increased pension in 1819 represented that he spent many months in hospitals until his “friends” – not his parents – “took him therefrom.”[38]He could not have wintered at Valley Forge, since Washington’s army did not reach that winter refuge until December 1777, well after Lewis was released from service.

A modest white tombstone, still intact and legible, placed in the Hilltown Lower Baptist Church cemetery by the Department of Military Affairs of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, describes Isaac Lewis simply as “Soldier in Revolutionary Army under General Washington.” The grave, marked by an American flag and veteran’s marker,[39]lies close to his birthplace and ancestral home, from which he traveled so far for his brief but unforgettable military service.

Epilogue

Isaac Lewis had a great-grandson also named Isaac Lewis, who enlisted in the Civil War in 1861. A sergeant at the second Battle of Bull Run, he like his namesake was shot through the leg (Lewises are perhaps just not nimble of foot). Less fortunate than his ancestor, this Isaac died several weeks later at a military hospital in Fairfax, Virginia. His parents at first unsuccessfully sought a survivor’s pension, then hired Horatio Sickel, former Colonel of the Pennsylvania Third Reserve, as an attorney, and eventually prevailed.

[1]Mary Jane Erwin, Morris Lewis and his Descendants(Philadelphia: Lewis-Jones Association, 1936), 6, 13, 42; Edward Mathews, “Lengel Farm,” The Intelligencer(Doylestown, PA), May 24, 1906, reproduced in Wanderings Through Historic Hilltown With Edward Mathews, Harry Adams, ed. (Bedminster, PA: Adams Apple Press, 1996), 45. Whether stirred by patriotism or family enmity toward the British, the younger Henry enrolled in the Hilltown Associators, a militia unit, in 1775, when he was nearly sixty years of age. Pennsylvania Archives, Ser. 5, Vol. 5:332-33.

[2]Richard Lee Baker, “Villainy and Maddness”: Washington’s Flying Camp (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2011), 9.

[3]Frances E. Devine, “The Pennsylvania Flying Camp, July – November 1776,” Pennsylvania History (Mansfield, PA: Pennsylvania Historical Association), Vol. 46, No. 1 (January 1979), 59-61; Baker, Villainy and Maddness, 52-53.

[4]Devine, “The Pennsylvania Flying Camp,” 62-65.

[5]“The Pennsylvania German in the Revolutionary War,” Pennsylvania German Society, Vol. XVI (October 5, 1905), 246; Letter from Judge William Watts, September 11, 1819 (from the Pension File of Isaac Lewis, No. S9748, National Archives).

[6]Morton L. Montgomery, History of Berks County (Philadelphia: Everts, Peck & Richards. 1886), 136-43.

[7]The amount promised and the amount paid are not recorded, but on September 3, 1777, Colonel Haller acknowledged receipt of “Four Thousand Dollars Equal to Fifteen Hundred Pounds,” an amount “to be Applied in Paying the Bounty “ordered to be paid to militia engaged in the Flying Camp for the State of Pennsylvania. Handwritten receipt given by Colonel Henry Haller, September 3, 1776 (Pennsylvania Historical Society, Society Collection).

[8]Pennsylvania Archives, Ser. 2, Vol. 3:572.

[9]Henry Phelps Johnson, The Campaign of 1776 Around New York and Boston (Brooklyn, NY: Long Island Historical Society, 1878), 122-23 & n. 1.

[10]Orderly Book of the First Regiment of the Flying Camp from Lancaster County, John Davis, Adjutant, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, entry for September 17, 1776.

[11]Devine, “The Pennsylvania Flying Camp,” 62-65.

[12]Montgomery, History of Berks County,145.

[13]Devine, “The Pennsylvania Flying Camp,” 65.

[14]Proceedings and Addresses, Pennsylvania German Society, Vol. XVI (Oct. 27, 1905), 23.

[15]George C. Heckman, “Pennsylvania-Germans in the Battle of Long Island Under Col. Peter Kichlein, of Northampton County,” The Pennsylvania German Society(1892), 15;

Thomas Warren Field, The Battle of Long Island: With Connected Preceding Events and the Subsequent American Retreat (Brooklyn: The Society, 1869), 149.

[16]David McCullough, 1776(New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005), 158-59. Heckman, “Pennsylvania-Germans in the Battle of Long Island,” 16.

[18]Henry Whittemore, The Heroes of the American Revolution and Their Descendants

(New York: The Heroes of the Revolution Publishing Co.,1897), 7-8; Field, The Battle of Long Island, 148-50; John J. Gallagher, The Battle of Brooklyn 1776 (New York: Sarpedon, 1995), 87-89.

[19]Michael Cecere, They Are Indeed a Very Useful Corps: American Riflemen in the Revolutionary War(Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, 2006), 43-44; McCullough, 1776,158; Field, The Battle of Long Island,146-50. Hand had participated in the siege of Boston. Henry Phelps Johnson, The Campaign of 1776, 112-13. While Berks County historian Milton Montgomery dates the transfer of Lotz’s troops to August 24, the transfer had to have taken place two days earlier. Lewis’s pension records conclusively demonstrate that he was not only on Long Island but had been wounded in a skirmish there on August 22, the day of the first British landings.

[20]Field,The Battle of Long Island, 150.

[22]Documents Appended to the Campaign of 1776 (David Library, Washington’s Crossing, PA), No. 423.

[23]Thomas J. McGuire, Stop the Revolution: America in the Summer of Independence and the Conference for Peace(Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books 2011), 97.

[24]Henry Phelps Johnson, The Campaign of 1776, 141-42. It is reported elsewhere that many of the fires started by American troops were quickly extinguished by Long Island natives, many of whom were pro-British in their sympathies. Joseph P. Cullen, “Battle for Long Island,” American History Illustrated (Gettysburg: National Historical Society),Vol. V, No. 4 (1970), 5.

[26]Field, The Battle of Long Island, 153.

[27]Isaac Lewis Certificate & Order for a Pension, October 25, 1778 (containing an August 17, 1778 declaration by Nicholas Lotz), Bucks County Courthouse, Miscellaneous Book 1, 220.

[28]Devine, “The Pennsylvania Flying Camp,” 66.

[29]Thomas Verenna, “The Spartans of Long Island,” Journal of the American Revolution, November 12, 2014, n. 29.

[30]McCullough, 1776, 178-83. For an interesting discussion of why the British did not renew the attack, see Gene Procknow, “Did Generals Mismanage the Battle of Brooklyn?” Journal of the American Revolution, April 20, 2017.

[31]See Mary C. Gillett, The Army Medical Department 1775-1819 (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, 2004), 65-72; Richard L. Blanco, “American Army Hospitals in Pennsylvania During the Revolutionary War,” Pennsylvania History (Mansfield, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical Association), Vol. 48, No. 4(October 1981), 347-51.

[32]Mary Jane Erwin, Morris Lewis and His Descendants, 42.

[33]United States Senate Report from the Secretary of War, in Obedience to Resolutions of the Senate of the 5th and 30th of June 1834, and the 3d of March, 1835, In relation to the Pension Establishment of the United States. [Pennsylvania Section] (Washington, D.C.: Duff Green, 1835), Ancestry.com – Pennsylvania Pensioners, 1835.

[34]Letter of Judge William Watts, September 21, 1821.

[35]1835 United States Senate Report, note 39. Lewis’s heirs collected a final pension payment of $38.40 following his death. Kathryn McPherson Gunning, Selected Final Pension Payment Vouchers 1818-1864, Pennsylvania: Philadelphia & Pittsburgh(Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, Inc., 2004), 1: 334.

[36]Inventory of the goods and chattles rights and estate of Isaac Lewis late of Hilltown Bucks County Deceas’d, (September 24, 1829), Bucks County Orphans’ Court, No. 2930. In addition to forty acres of land which Lewis had acquired from his father in 1785 for three pounds, then conveyed to his son in 1813, Lewis during his lifetime held another twenty acres in Hilltown Township which following his death were divided by his children.

[37]William Hart Davis, History of Bucks County Pennsylvania(Pipersville, PA: A.E. Lear, Inc. Publishers 1905), 347.

[38]Letter of Judge William Watts, September 21, 1821.

[39]History being unkind to facts, hopefully more so than this author, the marker incorrectly records his age at death as eighty.

6 Comments

What a wonderfully written article. My 6th Great Grandfather, and his brother, rough in the Revolutionary war, Peter Kern, out of Lehi, PA. They served in the Flying Camp also, Baxter’s Battallion.

Thanks for sharing his story in such a detailed and honorable way.

My wife and I are serious historians on George Washington, the founding fathers, and the American Revolution, and this piece is priceless.

Don, Thank you so very much. I had a fact here and a fact there, but you put them all together so well. Isaac was my great uncle (my roots go back to Rachel Lewis and Edward Jones). Two years ago we made the pilgrimage from Charleston, SC. to Chalfont. Not the easiest task to find (a church cemetery without a church), but we finally did. What a thrilling moment. We took a picture of my granddaughter in front of the tombstone, with the flag and “served with Washington” quite visible; it was shared on Facebook on the 4th of July. We received a wonderful response. Again thank you for such well-written piece. It will go in our archives with the Mary Jane (Lewis) Erwin family history and the Edna Lewis Loux book. Bill

I am honored to be a 4th great granddaughter to Isaac Lewis featured in “One Soldier’s Story; Isaac Lewis, in the Flying Camp, 1776” by Donald B. Lewis; and published in “Journal, of the American Revolution. Thank you cousin Donald B Lewis for writing and documenting the story of Isaac Lewis not only for our generation but for the generations to come.

David R Loux, my husband, served in the U. S Army during the Korean War and is buried at the same cemetery as Isaac Lewis, our ancestral grandfather.

Thank you for such the detailed and well documented article of the history of my ancestor Issac Lewis. I was fortunate to grow up within a 1/2 mile of the original family homestead and also the grave site of Issac. The family histories written by Mary Jane Erwin and then later by Edna Loux are cherished and brought attention to Issac’s service to me at a very young age. I no longer can ride my bicycle to visit his site. The trip is now a long car ride away, but I make if often.

Your article has answered many questions for me and has greatly enhanced my thoughts of Issac, his contributions to the cause, and the thanks that I carry dearly of his service for the hope of freedom and liberty. BRAVO and WELL DONE!

I thank you for an interesting story, especially as it involves a good deed done by my ancestor, Lt. Colonel Nicholas Lotz.

As descendants of Nicholas Lotz, my family and I will treasure this story and Isaac’s legacy.