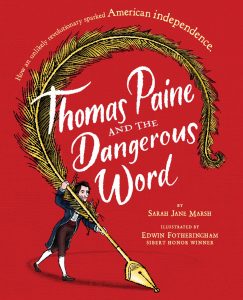

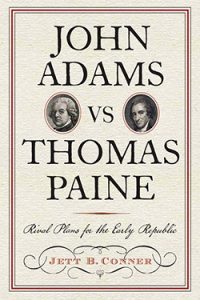

Today, May 29, 2018, Disney Hyperion is introducing young readers to the American Revolution with Thomas Paine and the Dangerous Word, an eighty-page picture book biography written by Sarah Jane Marsh[1] and illustrated by Edwin Fotheringham. The story focuses on Paine’s resilient early life and his call for independence through his famous pamphlet Common Sense. I consulted on Sarah’s book as a fact checker and have recently published my own debut book, John Adams vs. Thomas Paine: Rival Plans for the New Republic. As first-time authors with a shared interest in Thomas Paine, we were eager to compare notes and discover what common and unique experiences we had in researching and writing our books. To do this, we devised a set of questions – in bold – some common to both of us and some unique to each author.

Both of us have written books about Thomas Paine. Why Paine?

Jett: Thomas Paine caught my eye in a college history course. Actually, his words caught my ear. Growing up as a teenager in the era of Rebel Without a Cause, I discovered in Paine’s Common Sense a rebel with a good cause. Paine’s prose flowed easily and his radicalism appealed to my own rebellious thoughts as an undergraduate. But it was during my graduate studies on American political thought when I noticed that his recommendations for governance were largely overlooked or dismissed. So, I began to explore more carefully his political writings to see why.

Sarah: I think we both found a kindred spirit in Thomas Paine. For me, it was his “go-getter” attitude and optimism, backed up by his willingness to take risks – especially when speaking out on topics important to him. However, that same fearless spirit got him in trouble later in life. He wasn’t afraid to challenge the status quo, as he famously said, “a long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it a superficial appearance of being right.” Part of Paine’s brilliance was his ability to shock and awe his readers out of “fatal and unmanly slumbers” and encourage them to take action. Sometimes it takes a radical devil-may-care courage to push change, even when it might result in a belly flop. And I love Paine for that.

What particular challenges did you face in researching your books?

Jett: I’ll simply reply that as a political scientist, I’m often surprised how messy historical facts are. And here I thought the study of politics was a very inexact science! Then I remembered that John Adams once wrote: “Facts are stubborn things.” Trying to get the record straight when writing about Paine and his contributions to the American Revolution is hard. Because not all of his writings survived, and disputes continue to exist over exactly what he wrote, those of us studying Paine must depend on secondary sources and often-contradictory first-hand accounts of the man and events. (Even Paine offered some contradictory accounts of his own doings.) Once a story gets started and embedded in the literature it often gets passed along regardless of whether it’s substantiated.

Sarah: Absolutely. Separating fact from fiction was a challenge. Early in my research I encountered the claim that Paine did not sew corsets, but rather ship sails. This detail makes a big difference to my young audience, who delight in any discussion of underwear. Fortunately, J. L. Bell tackled this claim on his Boston1775blog and provided compelling evidence to support corset making. With relief, I was able to put that issue to rest.

The Journal of the American Revolution has been an instrumental resource for both Thomas Paine and the Dangerous Word and John Adams vs. Thomas Paine. How exactly did you use JAR when doing research?

Jett: I first turned to JAR as a place to publish an article on Paine, “The American Crisis Before Crossing the Delaware?” Since then, I’ve come to rely routinely on JAR as a resource. The Journal’s articles are well written and edited, and grounded with documented sources, many just a click away! And because I live in Denver, not exactly a hotbed of accessible resources on the American Revolutionary period, I often turn to the Journal first when searching for pertinent information regarding a topic.

Sarah: Likewise, living in Seattle, I’m even farther away from the cradle of liberty (which is Philadelphia, according to recent scientific methods – aka, the Super Bowl). I rely on JAR for current scholarship and discussion on the American Revolution. Your American Crisis article saved me months of detective work by analyzing the sources claiming Washington ordered Paine’s Crisis read aloud before crossing the Delaware. Because of your research, I prefaced my mention with “legend says,” a disclaimer that you noted with appreciation in your fact-checking summary!

Likewise, Ray Raphael’s article “Thomas Paine’s Inflated Numbers” helped inform my decision to use the more conservative 100,000 as the estimated number of Common Sense copies sold. Overall, JAR has been invaluable. It’s listed in my book as a recommended website.

Writing a book is challenging enough, but writing a narrative nonfiction book especially for children must have its own unique issues. Can you describe some of those?

Sarah: Writing narrative nonfiction for children is a balancing act. I am writing for my young reader, but I must also consider the needs of the illustrator, publisher, teacher, and librarian. I start with a vision of a story that I’m fired up to share with kids – what I want them to understand and the emotions I want them to feel. For Thomas Paine and the Dangerous Word, I wanted readers to experience his early life of ups and downs, his repeated failures, and yet his unflappable belief in himself – and in America. And how he used the persuasive power of words to advocate for himself and ultimately for America. Also, I wanted readers to understand the uncertainty of the time, concepts like liberty and reconciliation, and the dangerous nature of the word “independence.”

The trick is to channel all this inspiration and research into a compelling story within the format of a picture book biography. The magic of narrative nonfiction is that it reads like fiction yet is historically accurate. So one immediate challenge is employing fiction techniques, such as narrative arc, character, pacing, and dialogue, without straying from the facts.

Additionally, an ideal nonfiction picture book is under 2,000 words. This is my toughest constraint! I would love to give a more nuanced understanding of other political forces in play when Common Sense debuted. But I have to remember my audience is age six to ten, and my book is an introduction from which they can build more understanding. Fortunately, more explanation can be given in the backmatter: afterword, author’s note, timeline, bibliography, and source notes. I love doing school visits because I can share so much more history!

Thomas Paine and the Dangerous Word is a fully illustrated picture book. Tell us about working with an illustrator. There must be some unique challenges in coordinating your narrative with illustrations.

Sarah: I was thrilled when Disney asked Ed Fotheringham to illustrate, and even more thrilled when he accepted. He illustrated Those Rebels, John and Tom by Barbara Kerley.

Interestingly, the author and illustrator don’t usually have direct contact. Our work passes through our editor and art director who orchestrate the story. It is important for the illustrator to first create their vision based upon the completed manuscript. This begins with sketches that my editor sends to me for comment. It’s my job to weigh in if something doesn’t work historically. Over nine months, I commented on three progressive sets of illustrations.

One visual that was important to me was a sense of “the people.” Common Sense inspired public discussion – and action – in support of independence across all social levels, so I wanted readers to see that. (Similar to how “we the people” are engaged these days). We added visuals of colonists in discussion, which we later enhanced with quotes from the Suffolk Resolves and personal letters. And we made an intentional effort to show women, as they are often excluded from the narrative but were involved in political discussions at the time (hello Abigail Adams!).

It really is an amazing process of teamwork. Several times Ed’s illustrations brought me to tears. He added levels of detail and emotion beyond what I could convey in words.

As someone who teaches special units and gives talks in schools on the American Revolutionary era, what insights can you share about teaching history to kids?

Sarah: Kids are fascinated by real stories. They want to know exactly what happened, why, and how we know for sure. And they love knowing the story behind the story – the foibles, bad behavior and funny moments that bring the era alive for students. And surprisingly, kids love a compelling primary source. When we read aloud a voice from the past, often the wiggling stops and the kids sit transfixed, as if that person just entered the room. I remember one seemingly disengaged 5th grader who surprised me by volunteering to read aloud Hannah Bradish’s testimony accusing the King’s troops of stealing her aprons and negligee.

Most importantly, kids enjoy being empowered to think critically about our past and make connections to the present. They have a keen sense of injustice and are highly attuned to what they perceive as “fair” or “unfair.” Recently, as an example of a primary source, I showed Alexander Hamilton’s handwritten note on behalf of George Washington returning General Howe’s dog across enemy lines. One student asked why that simple act of kindness didn’t end the war? Because in a child’s view, what could be more important than the safe return of your lost dog?

What tips do you have to give authors who might be considering writing a children’s book about the American Revolution?

Sarah: First, determine what format of children’s nonfiction you’d like to write. (Author Melissa Stewart helpfully explains five types.[2]) Then study comparable books published in the last few years, even if it’s a different topic. If it’s narrative nonfiction like Thomas Paine and the Dangerous Word, analyze the fiction techniques. What is the narrative arc? How does the author blend expository writing with character, dialogue and setting? What is the pacing? If it’s a picture book, make a mock-up (or “dummy”) and see how the text reads with page turns.

Again, a big tip with nonfiction is you can pack more historical explanation in the backmatter. Sometimes I find the author’s note more fascinating than the actual story. Lastly, the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators(SCBWI) [3]is a great resource.

The American Revolution continues to be a popular topic for books. Why is there so much interest today in our founding era?

Jett: Of course, there’s Hamilton the musical. Without Lin-Manuel Miranda’s stage adaptation of Ron Chernow’s book, I’m not certain the American Revolution would be so popular right now. But the musical, emphasizing diverse actors and cultures, draws attention to current issues involving immigration, race and political divisiveness. Perhaps we wonder at times what’s going on now. And part of this is to take into account where we all came from and how our political ideals and system originated.

Sarah: Yes, and we are still such a young nation! I think we look to our past to untangle our present. As Ray Raphael said in A People’s History of the American Revolution,“we try to discover who we are by examining our roots.” The American Revolution is our origination story, a vast and complicated subject that each generation revisits through the lens of their time.

Also, I think we’re fascinated with ordinary people facing extraordinary challenges. We’re still uncovering those stories and learning from their lives. For example, Erica Armstrong Dunbar’s Never Caught provides an unforgettable and eye-opening look at George Washington’s relentless pursuit of his runaway slave, Ona Judge. Through her story we learn about courage and resilience from a remarkable woman and expand our understanding of slavery and of Washington himself.

Why do you think Thomas Paine deserves special attention? Will he ever achieve familiarity with the American public similar to other Founders such as John Adams?

Jett: Thomas Jefferson said that Paine was the “first public advocate for American independence.” That advocacy, of course, came in Common Sense. For that work alone he will always have a special place in American history. But except for that sensational pamphlet and a few famous words written later in the American Crisis No.1– “These are the times that try men’s souls” – Paine’s public writings on American politics are not well known. Sarah Franklin Bache said that if Paine wanted to be famous, he should have died after he’d written Common Sense. But he did go on to publish very controversial things later – The Age of Reason, for example, which attacked organized religion, including Christianity, and a bitter and public letter to President Washington accusing him (with some justification) of abandoning his old revolutionary friend while he was imprisoned in France during that country’s Reign of Terror. Those things alienated Paine from many of his old friends and made him infamous in this country upon his return from Europe in 1802. Even President Jefferson, who warmly received Paine at first, eventually cooled to what had been a long-lasting relationship. At Paine’s death, six people attended his burial; not one of them was Revolutionary era figure. Historian and writer Jill Lepore wrote in the New Yorkera number of years ago that Paine is “at best, a lesser Founder.” He will likely remain in the shadows of Jefferson, Adams and other Founders.

Sarah: Now I feel sad for Paine all over again! I’ll add that Paine’s former enemy-turned-zealous-fan dug up Paine’s bones and carried them to England where they were lost over time (as written about in The Trouble with Tom by Paul Collins). I haven’t yet dared share that fact with students as the ensuing questions would totally derail my presentation. I agree that Paine’s peers attributed much of the success of the American Revolution to his writings. Even feisty John Adams worried that “history is to ascribe the American Revolution to Thomas Paine.” But by later attacking the two most untouchable subjects – religion and George Washington – Paine was frozen out of society. However, I am hopeful he’ll have his day in the sun. John Adams had an HBO series, Hamilton a musical; perhaps Paine could have a Hollywood movie (wink wink to my publisher Disney!).

John Adams vs. Thomas Paine focuses on the two men’s debate about what kind of government should replace British rule. How does this debate inform fundamental questions about our democracy today?

Jett: The debate between Adams and Paine was about democracy: how democratic should the republic be? Both were staunch supporters of independence but the similarities in their politics ended there. Paine wanted government to be based on a “more equal” representation of the people, for example. Adams resisted that idea, believing that the people were not entirely to be trusted to govern themselves and that class distinctions and a scheme of representation reflecting that should be preserved. And while Adams championed checks and balances and other features of government complexity, Paine favored more simple forms of democracy and political accountability. The fact that a president can be elected by winning the Electoral College but not the popular vote, for example, is a remnant of Adams and other Founders’ fear of majority rule and arrangements designed to limit it. Paine’s belief in popular government on the other hand is more in line with those who advocate abolishing the Electoral College and/or supporting measures for increasing voter participation.

Sarah: I’d like to add that I learned a lot from John Adams vs. Thomas Paine. I wish I had your book back in 2016 and could incorporate key points into my author’s note. (I will forever want to add to my author’s note! As Paine said, “I seldom passed five minutes without acquiring some knowledge.”) As I move forward talking about Paine, I appreciate having a better understanding of Common Sense’s contributions to political thought beyond a call for independence. So thank you for that.

What do you see as two or three takeaways for readers of your book?

Jett: There are two takeaways from John Adams vs. Thomas Paine that I would mention. One, Thomas Paine was more than just a rebel rouser. Common Sensehelped shape American thinking during the formative period of the American Revolution and early constitution building. Two, John Adams’s fears about Paine’s “democratical” ideas in Common Sense pushed him to publish his Thoughts on Government in response. The debate started by these two early pre-Independence pamphlets shaped and continues to inform American political thought. And Paine’s political views have proven to be enduring: America is far more democratic today than it was in 1776. His call for “more equal” representation had some influence on that.

Sarah: For young readers of Thomas Paine and the Dangerous Word, I hope Paine’s life encourages them to persist through the ups and downs in life. This is a topic close to my heart, as suicide is the second leading cause of death for teenagers in the U.S. (We still have “dangerous” words in our society, and like Paine, we need to speak out to break the fear and stigma). Which leads to my second takeaway: I hope young readers are inspired to be courageous and use the persuasive power of words to speak out on topics important to them. Lastly, I hope my book sparks curiosity to read more and learn more.

What are you working on next?

Jett: I am slipping, with some trepidation, into the nineteenth century for my next research project, and am thinking, after recently reading Washington Irving’s The Adventures of Capitan Bonneville, of composing a small book on Bonneville’s western travels for a young adult audience. Benjamin Bonneville was one of Paine’s godsons and, at age thirteen, one of the six attendees at Paine’s burial in New York that I have already mentioned. He went on to graduate from West Point, had a full career in the U.S. military and in 1832 – taking a leave from the service – was the first person to lead a wagon train over South Pass in Wyoming on the Oregon Trail. He attended and reported on the great rendezvous of fur traders and American Indians that year west of the Tetons. At least, my research on this topic will be a bit easier because of the vast resources readily available on the American West in the Denver Public Library. Plus, the opportunity for some travel nearby to neat sites in Wyoming and Idaho is pretty nifty too!

Sarah: I am working on a second book with our team at Disney-Hyperion, Most Wanted: John Hancock and Samuel Adams. It’s a light-hearted look at the revolutionary odd couple that General Gage exempted by name in his 1775 pardon. I too am daunted by my project as it contains some revered history and I want to get it right … in less than 2000 words! Also, writing is a lonely job, so I’m excited to get out and talk Thomas Paine and the American Revolution anywhere and everywhere. It’s been a joy discussing our joint fascination on these subjects with you, Jett. It would be lovely to do a talk together someday!

[2]/www.youtube.com/watch?v=P4vd1XEPu6E

[3] /www.scbwi.org

3 Comments

I saw this book in the store yesterday. My kids are a bit young for it now but I told my wife it’s my next birthday present. I’m excited to eventually read it to my kids.

Sarah’s new book is special and something the kids will enjoy. It also makes a great birthday present, too!

Thanks Nathan! I just heard from a woman who said her husband read the book and cried. It is definitely for adults too!