Antoine Félix Wuibert was one of the earliest foreign volunteers to the War of the American Revolution, arriving even before the United States pronounced its independence from Britain. Although commissioned as an officer of engineers, he served his newly-adopted nation in a variety of roles throughout the entirety of the war, popping up in key places like the Battle of Fort Washington in 1776, with John Paul Jones at the Battle of Flamborough Head in 1779, and at Fort Pitt in the Western Theater after 1781. After the war he battled with domestic problems and failed land deals even as he became an active abolitionist in the Philadelphia area. Unlike his better-known and equally ubiquitous American counterpart, Joseph Plumb Martin, he saw action on both sides of the Atlantic, on both land and sea; and also unlike Martin and the fictional Forrest Gump, he never left a first-hand account of how he became part of so many pivotal events in the nation’s history.[1]

Wuibert was baptized as Antoine Félix Wibert on January 8, 1741 in the Army garrison city of Mézierès in the Ardennes in northern France, known later as the site of the Royal Engineering School.[2] He was apparently the eldest in the family, with a brother George born in 1742, a sister born in 1743, and another sister after that. His father Jean-Baptiste Wibert was a collector of taxes on tobacco. Wuibert went to Saint Domingue (today Haiti) at age twenty-one in 1763, just as the Seven Year’s War was coming to an end. There he served as a surveyor under his godfather Antoine Jean Jacques Du Portal, an engineering general officer who became director-general of fortifications on Saint-Domingue in 1764 and was promoted in 1767 to lieutenant general.[3] Wuibert served under Du Portal until the latter’s return to France in 1769 and retirement in 1770. Wuibert continued to receive financial support from his godfather until Du Portal’s death in 1773, after which he was left “without resources” and came to America on his own. The manner and date of his arrival are unknown, but as with many of the earliest French volunteers coming from Canada and the Caribbean to join the American cause, it was done entirely without any official or unofficial support from the French government.[4]

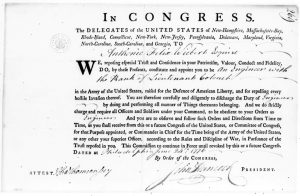

Wuibert first came to American attention on June 24, 1776 when he was commissioned by the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia as “Anthony Felix Wiebert,” with the “rank of Lieutenant Colonel” in the Army, and tasked to “to discharge the Duty of Engineer.”[5] Wuibert’s commission bears the unmistakable signature of the President of the Congress, John Hancock. It is worth noting that on that date, the Congress was still working on the Declaration of Independence, but it had already set upon the name for the new nation; Wuibert’s commission was the very first use of the term “The United States” on any official document.[6]

The spelling of Wuibert’s family name had many variants: at baptism it was Wibert, the Congress commissioned him as Wiebert, and it was reported at various times as Waibert, Weibert, Wybert, Wuybert, Wulbert, Wuibert de Mézières, Vaïbert, Vibert, Viebert and Ouibert. Only later in life did he settle on the spelling Wuibert. He also alternatively used either Antoine, Anthonie or Anthony as his first name, with or without Félix. However he spelled his name, Antoine Félix Wuibert immediately went into the service of the United States and continued throughout the war.[7]

Wuibert was placed under the overall command of Brig. Gen. Thomas Mifflin, then the army’s quartermaster general, though he reported directly to Col. Rufus Putnam, chief of engineers of the works of New York. Wuibert was assigned to construct Fort Washington and an artillery redoubt at Jeffery’s Hook, both at the northern end of Manhattan Island, to prevent the British fleet from ascending the Hudson River. Despite Putnam’s and Wuibert’s best efforts, the solid bedrock made it almost impossible to erect the complex of ditches, casements and earthworks required to fortify the strongholds against a British assault. After the Battle of Long Island in August 1776, the American troops were pushed across Manhattan to White Plains and New Jersey, although George Washington decided to leave a large garrison, under the command of Colonel Robert Magaw, to defend the Manhattan forts. Faced with superior British and Hessian forces, Magaw elected to stay put and fight rather than withdraw. On November 16, General William Howe’s troops overran Fort Washington from three sides and captured almost 3,000 troops, including Wuibert.

Even though he was a commissioned American officer, the British treated the French-born engineer as a neutral combatant and placed him in the provost guard jail in New York City, instead of in a military prison. Washington complained bitterly to Howe about the “severe treatment of Mons. Wiebert.”[8] By November 1777 he had been shipped from New York aboard HMS Sandwich, incarcerated at the Savoy Prison in London, which was primarily used for holding military deserters, then placed with other French prisoners aboard the prison hulk Princess Amelia at Portsmouth, where he was “ill, barely clothed and had all of his belongings pillaged.” Entreaties by his family to Benjamin Franklin, then an American commissioner to France, and to the French foreign minister Comte de Vergennes had no effect – Vergennes flatly stated that because Wuibert “had gone without permission to the service of the Americans” he could do nothing about his fate. Wuibert was not released but instead transferred to the notorious Forton Gaol in Gosport. This was really a collection of ramshackle wooden huts and tumbledown shacks, which had once served as a hospital but was now pressed into service to confine American sailors and other supporters of the American revolution. There he languished for the next year.[9]

Franklin had been working for almost two years to improve the conditions for these American prisoners and negotiate a cartel of exchange for British prisoners, captured by American privateers like John Paul Jones, who were being held in Texel in the Dutch Republic. In the fall of 1778, Franklin and his friend David Hartley, member of Parliament and future architect of the Treaty of Paris (1783), wrote back and forth across the English Channel to finalize the terms of the exchange, while Franklin simultaneously worked with the French Minister of the Navy, Antoine de Sartine, to find a suitable location. By December 1778 the agreement to exchange prisoners had been reached, and on January 1, 1779, Franklin informed Hartley that the exchange would take place in the French port of Nantes.[10] Wuibert was released almost immediately, for by the end of January he was at his sister’s home in Paris after visiting his father in the Ardennes. This occurred even before the first formal exchange on April 2, when a shipload of ninety-seven American prisoners arrived at Nantes, to be placed under the care of Franklin’s agents.

Wuibert wrote to Franklin on January 25, stating that he had at first “followed your (Franklin’s) orders and went to the home of Mr. Lee (Arthur Lee, Franklin’s co-commissioner), but he was told that Lee was very dangerously ill.” (In fact, Lee was not at all ill, as his journal indicates a lively schedule in late January. He was likely avoiding Wuibert.) Wuibert, who signed himself as “Wuybert” and continued to write in French despite years of American service, explained that he was unable to stay much longer with his sister, as her husband – presumably M. Troyes, who had written to Franklin in 1777 asking for his help with Wuibert while in prison – was due to arrive home from his campaigns in the French military. “While it is true that I am in my old homeland,” Wuibert told Franklin, “I would prefer to be in America, which is my Real country.” He then got to the heart of the matter. After two years of harsh imprisonment at the hands of the British, he did not want to stay in France and recover, but rather was “anxious to return to service” of the United States. With increasing passion, Wuibert told Franklin, “I am even more eager to exact vengeance on the barbarities which I have suffered at the hands of the Enemy which all nations detest … if I cannot, I shall regret all my life that I did not take my revenge. I burn to return to my service … [signed] a True son of our cherished Liberty.”[11]

Franklin took this plea to heart, for by May 1779, Wuibert was in Lorient, France, as an officer of the Marines under the command of John Paul Jones, who was fitting out his ship Bonhomme Richardfor a new assignment directed by Minister of the Navy Sartine. France and Spain had signed a treaty of alliance early in 1779 that committed both navies to invade Britain. While this massive assault of over 150 allied French and Spanish ships approached Britain in the summer of 1779, Sartine tasked Jones to lead a small French-American squadron around the British Isles to distract the Royal Navy and hopefully divert some of their vessels to follow him. The British admirals of course did not fall for this obvious ploy, but Jones’ epic campaign would soon go down as one of the great exploits in American naval history.[12]

While Wuibert was at Lorient, he happened to meet John Adams, who had been one of Franklin’s co-commissioners in Paris but was now returning to the United States. Adams, who was certain he could read a person’s character simply by studying his appearance, was mistakenly unimpressed with the man who had already proved his mettle more than once fighting for the American cause; he noted in his diary for Friday, May 7, 1779: “Colonel Weibert has something little in his face and air, and makes no great discovery of skill or science.”[13] Adams would be proved wrong in the coming months.

On August 14, just as the massive French and Spanish armada was preparing to enter the English Channel (the assault would fizzle out due to an epidemic of dysentery), Jones’ squadron departed the roadstead at Lorient to sail around the British Isles, in an attempt to draw off the Channel Fleet from its real target. Jones’ squadron consisted of Bonhomme Richard, a converted French merchant ship carrying forty cannon; the Continental thirty-six-gun frigate Allianceunder the command of Pierre Landais, a French volunteer commissioned in the Continental Navy; and three French warships detached by Sartine to serve under Jones. Sartine’s instructions to Jones, endorsed by Franklin, specifically called for commerce raiding on the high seas and made no mention of landings, but Jones had other ideas. To support his intended amphibious raids, he embarked 137 marines aboard Bonhomme Richardinstead of the usual 60 marines that would be assigned to a frigate of that size to provide security and musketry support. These were not Continental Marines but rather members of France’s Irish Regiment of Walsh-Serrant, whose motto Semper et Ubique Fidelis(Always and Everywhere Faithful) would later serve as inspiration for the United States Marines. Antoine Félix Wuibert was one of five French officers in charge of this regiment.[14]

On the afternoon of September 23, Jones’ squadron was cruising off Flamborough Head on the Yorkshire coast, just south of Scarborough, when they spotted a large merchant convoy of timber-carrying ships, escorted by the frigate HMS Serapis and a smaller armed merchant ship Countess of Scarborough. Jones immediately set out towards the convoy while ordering the crew to their combat stations. Wuibert was in charge of Bonhomme Richard’s principal battery, the twenty-eight 12-pound guns on the upper deck, which were to fire split shot into Serapis’ rigging in order to disable it. The Irish marines were sent to the poop deck and fighting tops (the highest parts of the masts) to fire down upon the enemy ship. Aboard Serapis, Captain Richard Pearson made similar preparations, while he signaled the convoy to seek safety under Scarborough Castle’s guns and moved to intercept the enemy squadron. His ship was less than six months old, with a fast hull and armed with forty-four cannon, most of which were 18 pounders. Bonhomme Richard was an elderly thirteen years old, with a slow merchant hull and fewer, much lighter guns. There seemed no chance that Jones could prevail.

Night was falling when the two ships closed to within hailing distance – about one hundred yards – then ran up their colors while simultaneously firing broadsides. Wuibert’s 12-pounders were cutting up Serapis’ masts and spars, but the British ship still outsailed the American to achieve better firing positions. Pearson’s better-trained crew could also reload and fire more quickly, which coupled with the heavier weight of shot meant that Serapis was tearing apart Bonhomme Richard at a faster rate than the American could damage its opponent. Jones saw that his only chance was to have his crew grapple and lash the two ships together, so that Pearson could no longer run out some of his cannon. As night fell, the two ships drifted northwest lashed side-by-side, Serapis’ stern hove up against Bonhomme Richard’s bow. Some of Serapis’ batteries still managed to blast away, silencing the rest of the American’s guns. Countess of Scarborough stood off from the action, its captain unwilling to fire at the American ship for fear of also hitting Serapis. Pierre Landais aboard Alliance showed no such reserve, firing into Serapis three times while part of each broadside also scythed into Bonhomme Richard, killing and wounding British and American sailors alike. After over two hours of battle, the gun duel was clearly going in Pearson’s favor. He called to Jones, “Have you struck?” Jones fired back, “I may sink, but I’m damned if I’ll strike!”[15] It was clear indeed that Bonhomme Richard was settling lower in the water, and that time was running short.

If the British were to succeed, they would have to get clear of the Americans and finish them off with gunfire. If the Americans were to win before they sank, they would have to kill and maim as many of Serapis’ crew as possible. With his cannon disabled or destroyed, Wuibert, wounded in the thigh and arm,[16]rejoined the marines under his command as they rained musket balls on the British sailors trying to cut away the grappling hooks. Every British seaman who reached the bulwarks was hit; the fire from the Irish regiment was so accurate that the British thought they were using rifles. By now the below-decks of the American ship was almost uninhabitable due to flooding and cannon fire, while the British sailors dared not venture above-deck. Half of each ships’ crew lay dead or wounded. Just then, one of Jones’ sailors crawled out along Bonhomme Richard’s yards and threw grenades on to Serapis’ deck, one of which bounced through a hatch and ignited gun cartridges below. The resulting explosion and deflagration ran the length of the gun deck, killing or wounding fifty of the men crammed there and putting the rest of the guns out of action. By 10:30pm, Pearson decided to strike his colors. The convoy he was assigned to protect was safely at Scarborough, and while offering one’s sword to the commander of a sinking ship might be a disgrace, he believed he could honorably surrender to twowarships, one of which, Alliance, was still an active threat. Further bloodshed was unwarranted, a decision later upheld when Pearson was knighted for saving the convoy. John Paul Jones transferred his command to Serapis the next day, as Bonhomme Richard gradually sank beneath the waves. Jones also took Countess of Scarborough as a prize.

A week later the squadron was at the island of Texel in the Dutch Republic. After discussions with the Dutch authorities, Jones was permitted to land and house his almost 500 prisoners from the two British ships at the Fort de Schans on Texel. In an ironic twist, Jones named Wuibert as “Governor general over the wounded, and the Soldiers, &c. that are destined this day to conduct them to that Fort on the Texel,” and ordered him “to guard them there until further orders… [and] to take care, that no person under your command may give any cause of complaint whatever to the Subjects or Government of this county; but on the contrary, to behave towards them with the utmost complaisance and civility.” Given the atrocities that Wuibert had endured at the hands of the British, it would have strained the very fibers of his being to show “complaisance and civility” the British prisoners, until they were exchanged for French prisoners in December 1779. Wuibert himself wanted nothing more than “return as soon as possible to America … to renew my service as an engineer.” Jones had the highest regard for Wuibert and did not want him to leave, but nevertheless acceded to his request and released him from service to return to America[17].

On December 27, 1779 Jones took command of Alliance and sailed from Texel with Wuibert aboard, bound first for La Coruña in Spain and then Lorient in France. On January 8, 1780 while in the Bay of Biscay off Spain, Jones captured the Dutch merchant ship Burke Boschsailing from Liverpool to Livorno with British cargo. The following day he gave command of the prize to Peter Faneuil Jones with orders to return the ship to Philadelphia, placing four of John Paul Jones’ crew, including Wuibert, aboard. The Dutch vessel was leaky, so they made for Martinique. However, on March 10, 1780 they were overtaken and captured by the British frigate HMS Greyhound. Wuibert was once again a British prisoner, and with the rest of the prize crew he was brought first to Saint Lucia, then to Barbados, then to Saint Kitts and finally to Jamaica. While the American prisoners were sent on to Portsmouth in Britain, Wuibert was exchanged on August 5, 1780 and sent to the French colony of Saint Domingue.[18]

Wuibert was nothing if not tenacious; despite being in Saint Domingue, where he had spent his early professional career and could likely find useful employment, he still “burned” to return to the fight in the United States. Wuibert made yet another attempt to find passage back to America, this time aboard the Continental Navy frigate Confederacy, Capt. Seth Harding in command, which had come to Cap François (today Cap-Haïtien), the main port of Saint Domingue, in January 1781 to take on supplies for the war. The ship departed for Philadelphia on March 15, 1781, laden with uniforms, produce and six passengers, including Wuibert. It never made it there. On April 14 off the Delaware Capes, Hardy was intercepted by the British frigates Roebuck and Orpheus. Outgunned and not wanting to lose lives unnecessarily, Harding struck his colors without a fight and Confederacy was taken to New York. Wuibert was imprisoned for a third time, now aboard the notorious prison ship HMS Jersey (nicknamed “Hell”) in Wallabout Bay off Brooklyn, before he was allowed to reside on parole at Flatbush, Long Island. Finally, on September 3, he was exchanged for what would be the last time.[19]

Wuibert arrived in Philadelphia on November 8, 1781, where he applied to the Congress to resume his duties as an engineer. By then the news of the French-American victory at Yorktown was already known, though neither George Washington nor the Congress believed the war itself was over; a man with Wuibert’s engineering skills was still needed. The head of the American Army Corps of Engineers, the French volunteer Louis Lebègue Duportail, was about to return to France but on December 1, he recommended to Washington that Wuibert be given a position worthy of his experience:

I ought to Say a word, to your Excellency, of Mr De Vibert [Wuibert] who is exchanged. He is the oldest Lieutenant Colonel in the Corps, & Should naturally take the Command where ever Colonel Laumoy [another French engineer] were not. I cannot Say anything disadvantageous of him. By what I heard from Paul Jones, under whose command he happened to be for Some Time, he appears to be a very brave Man. But having not had the necessary Instructions to make an Engineer, and having been deprived, by his long Captivity and his Voyages by Sea of the Opportunities of practicing in his profession of Engineer, I think it would not be So proper to employ him in your Army but rather to Send him to Albany or Fort Pitt with the Troops which are actually in those parts.[20]

Wuibert remained on garrison duty in the Philadelphia area through early 1782. On February 5, 1782 he was married by the Rev. William Rogers to Altathea Garrison, widow of John Garrison, and they presumably lived in her home in Southwark in the southern part of the city. By April, Wuibert was serving under Brig. Gen. William Irvine as chief engineer at Fort Pitt, the American headquarters for the western theatre of the war. He returned to Philadelphia in May as his wife was “confined to her Death-bed,” but by August she had recovered sufficiently that Washington instructed him to return to Fort Pitt, where he remained until the following year. He moved back to Philadelphia, where on May 4, 1783, along with the other members of the Corps of Engineers, he signed an agreement to accept five years of commutation pay in lieu of half-pay for life. He was probably discharged from the service on November 3, 1783 and at some point, became naturalized as an American citizen.[21] Wuibert, along with other former army engineers, joined the original Society of the Cincinnati soon after it was formed May 13, 1783, and in the fall of 1783 became one of the founding members of State Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania. Sometime after that – the date is not certain, but likely 1784 or 1785 – he transferred his membership to the French branch of the Society, the Société des Cincinnatis de France.[22]

At about this time Wuibert left Philadelphia to return to Cap François, Saint Domingue, for on December 5, 1785 he wrote from there to Thomas Jefferson, then the American ambassador to France, asking his help in recovering his share in the prize money from the capture of HMS Serapis back in 1779. Wuibert was by now in poor health and desperate financial straits, and largely dependent on his friend Nicolas Odelucq, a wealthy plantation owner and a captain of the local militia (he was also known for having financed the first balloon flight in the Americas, in 1784 in Saint Domingue, ten years before the first flight in the United States). Jefferson promptly wrote to the official at Lorient, Chef d’escadre (roughly equivalent to rear-admiral) Antoine-Jean-Marie Thévenard, obtaining the authorization to pay the prize money from French naval accounts. A further flurry of letters with the banker Ferdinand Grand ensured that Wuibert would receive the payment at Saint Domingue via the Marquis de Galliffett, one of the wealthiest plantation owners there. Wuibert, presumably in better heath both physically and fiscally, returned to his wife Altathea in Philadelphia.[23]

Wuibert’s marriage was not a happy one, for on November 21, 1787, he filed for divorce. Divorce between Catholics (he was French, she was of Irish descent) was very rare, and the divorce proceedings were ugly. Antoine accused Altathea of being “lewd,” “infamous” and of having been an adulteress since the year after they were married; she accused him of frequent absences and of having gonorrhea. These last two were demonstrably true, and also linked; Antoine had undoubtedly contracted the disease while at Saint Domingue, where every seventh non-slave woman in the colony was a prostitute. By 1788 the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania granted their divorce, and he moved to Upper Dublin Township, north of Philadelphia.[24]

Wuibert’s marital troubles were over, but his financial ones were not. On November 5, 1789 he was granted 450 acres of land in Ohio as part of the Army’s military land warrants for Revolutionary War veterans. He submitted his taxes to George Taylor, Jr., the Philadelphia broker of John Mathews (Matthews) and Ebenezer Buckingham, the military’s agents for the warrants. A few months later he was informed that an Ohio sheriff had seized his lands for non-payment of taxes, and he was never able to find Mathews again; even his further entreaties to Thomas Jefferson had no effect, and it appears he was never able to recover his seized property. In 1790 he was one of the first investors in what would turn out to be a falsified land deal to refugees from the French Revolution. The Scioto Company was formed to sell land along the Scioto River in what would become the city of Gallipolis, Ohio. But the Company did not own the rights to the land, and many of the initial investors lost their entire investment. Wuibert lost his investment of a home and several lots of land.[25]

At the same time, Wuibert took up the cause of abolition in the land he now called home. He had seen the horrors of slavery first-hand during his stay at Saint Domingue, where enslaved African outnumbered free whites by a ratio of ten to one. In letters from Saint Domingue to his Philadelphia business agents Etienne Dutilh and John Godfried Wachsmuth, he described the first slave uprisings in what would become the Haitian Revolution, 1791-1804, which led to the independence of the Saint Domingue from France. In 1788 Wuibert became one of the founding members of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, and was active in the society for many years. Wuibert was also connected to Philadelphia’s scientific community, for the witness to his last will was Amable J. Brasier, a naturalized citizen from France and member of Philadelphia National Academy of Sciences.[26]

Wuibert finally found marital happiness in his adopted country. On October 17, 1805, Wuibert was married for the second time at Holy Trinity Catholic Church, Philadelphia, to Jeanne (Jane) Marie Magdalene née Moreau, the widow of Jean Pourcent of Montendre, Saintonge, France. They had evidently been married earlier that year in a civil ceremony, for his last will, written on September 25, 1805, named his “beloved wife Jane Magdalen Wuibert” as his sole heir. He adopted her children Jean Denis (born 1796), and Laure Antoinette (born 1799) as his own step-children. They lived at first in Frankford in Philadelphia County and then in Allentown, Pennsylvania. With Jeanne Magdalene he had two more children, Antonio Felix Wuibert (born December 2, 1806), and Jeanne Adelaide Marie Wuibert. His daughter Jeanne Adelaide was married in a religious ceremony on November 15, 1832 at the Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Philadelphia, and on January 4, 1833 in a civil ceremony at the French Consulate in Philadelphia, to François Pelet, a native of Bordeaux.[27] We do not know if Antoine Félix Wuibert was alive to witness his daughter’s wedding, for after 1807 all trace of him disappears. His place of burial remains unknown.

[1] Joseph Plumb Martin, A Narrative of a Revolutionary Soldier(New York: Signet Classics, 2010); Winston Groom, Forrest Gump(New York: Doubleday 1986), and the 1994 movie Forrest Gumpdirected by Robert Zemeckis and starring Tom Hanks.

[2]Archives Départementales des Ardennes (Ardennes Departmental Archives), GG 23, Charleville-Mézières, France. Microfilm 5Mi 15 R 8 p. 323. Thanks to the late Jacques de Trentinian for locating these.

[3]Archives Nationales d’Outre-Mer (Overseas National Archives), FR ANOM COL D2C 94 fol. 159, Du Portal (Antoine Jean Jacques). Du Portal was no relation to Louis Lebègue Duportail, the future head of the American Army Corps of Engineers.

[4]Larrie D. Ferreiro,Brothers at Arms: American Independence and the Men of France and Spain Who Saved It(New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), 122-124.

[5]Continental Congress to Antoine F. Wuibert, June 24, 1776, Printed Commission, www.loc.gov/item/mgw445278/.

[6]Curtis P. Nettles, “A Link in the Chain of Events Leading to American Independence,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series 3/1 (Jan. 1946), 36-47.

[7]A short but comprehensive biography of Wuibert is in John D. Kilbourne, Virtutis Praemium: The Men Who Founded the State Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania. 2 vols. (Rockport, Maine: Picton Press, 1998), 2: 1004-1007. Wuibert summarizes his career in a 1785 letter to Thomas Jefferson concerning his rights to prizes and compensation for service: www.loc.gov/item/mtjbib001441/.

[8]General Washington to Lieutenant-General Howe, Bucks County, December 12, 1776, in The Writings of George Washington, vol. 4, Jared Sparks, ed. (Boston: American Stationers Company, 1833-1839), 4: 215.

[9]M. Troyes to Franklin and Deane for Antoine-Felix Wuybert, November 30, 1777, franklinpapers.org/franklin/framedVolumes.jsp?tocvol=25; Henri Doniol, Histoire de la participation de la France à l’établissement des États-Unis d’Amérique (History of the French participation in the establishment of the United States)(Paris: Imprimerie National, 1886-1899), 2: 401-402.

[10]Bob Ruppert, “Benjamin Franklin: Our Salvation Depends on You,” Journal of the American Revolution, May 23, 2017, allthingsliberty.com/2017/05/benjamin-franklin-salvation-depends/.

[11]Antoine-Félix Wuybert to Franklin, Paris, January 25, 1779, franklinpapers.org/franklin/framedVolumes.jsp?tocvol=28; Richard Henry Lee and Arthur Lee,Life of Arthur Lee, LL.D. (Boston: Wells and Lilly, 1829) 1: 406-407.

[12]Charles R. Smith, Marines in the Revolution: A History of the Continental Marines in the American Revolution, 1775-1783(Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1975), 227-235.

[13]John Adams, Charles Francis Adams, The Works of John Adams(Boston: Little, Brown, 1850-1856), 3: 198.

[14]Of several hundred books on Jones’ voyage and battle, I have relied on two for this essay: Jean Boudriot (trans. David H. Roberts), John Paul Jones and the Bonhomme Richard: A Reconstruction of the Ship and an Account of the Battle with HMS Serapis(Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1987); and Thomas J. Schaeper, John Paul Jones and the battle of Flamborough Head: A Reconsideration(New York: Peter Lang, 1989).

[15]“I may sink, but I’m damned if I’ll strike!,” or words to that effect, were recorded in contemporary accounts of the battle. The apocryphal “I have not yet begun to fight!” was only cited almost a half-century later by one of Jones’ officers, Richard Dale.

[16]Mercure de France, Saturday December 18, 1779, 187-188.

[17]Wuybert (Wibert) to John Paul Jones aboard American warship Serapis, October 10, 1779, inThe Papers of Benjamin Franklin, 30: 511; Jones to Wuybert, November 1, 1779, Ibid., 31: 30.

[18]John S. Barnes, ed., The Logs of the Serapis – Alliance – Ariel Under the Command of John Paul Jones, 1779-1780(New York: Naval Historical Society, 1911), xxi-xxii, 48-54; Peter Faneuil Jones to Franklin, Dunkirk, December 14 and 15, 1780, in The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, 34: 160, 163; Kilbourne, Virtutis Praemium1006. Peter Faneuil Jones was previously an American sailing master with no direct relation to John Paul Jones.

[19]Douglas H. Robinson, “The Continental Frigate Confederacy,” Nautical Research Journalvol. 8 no. 2, March-April 1956; Asa Bird Gardiner, The Order of the Cincinnati in France(Rhode Island State Society of Cincinnati, 1905), 167.

[20]Antoine-Jean-Louis Le Bègue de Presle Duportail to George Washington, December 1, 1781. rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/default.xqy?keys=FOEA-print-01-02-02-1471.

[21]Kilbourne, Virtutis Praemium1006; Wuibert to Washington from May 5, 1782, founders.archives.gov/?q=wuibert&s=1511311111&r=22; Washington to Wuibert, August 6, 1782. rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/default.xqy?keys=FOEA-print-01-02-02-3055

[22]Gardiner, The Order of the Cincinnati in France, 167; Kilbourne, Virtutis Praemium, 1006.

[23]Wuibert to Thomas Jefferson, December 5, 1785,inThe Papers of Thomas Jefferson (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950-present), 9: 78–79; Jefferson to Ferdinand Grand, Paris, January 14, 1787, Ibid., 11: 39-40.

[24]Merril D. Smith,Breaking the Bonds: Marital Discord in Pennsylvania, 1730-1830(New York: NYU Press, 1992), 154; James E. McClellan III, Colonialism and Science: Saint Domingue in the Old Regime(Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), 60.

[25]Clifford Neal Smith, Federal land series; a calendar of archival materials on the land patents issued by the United States Government, with subject, tract, and name indexes(Chicago; American Library Association, 1972), 1: 55; Wuibert to Jefferson, Upper-Dublin Township, Montgomery, County, State of Pennsylvania, December 14, 1801, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-36-02-0072; Anita Short, “Washington County, Ohio, Wills and Estates, 1789-1799,” Gateway to the Westvol. 7-8, 42.

[26]“E. Wuibert Correspondence, 1788-1803, Merchant; letters, mostly in French to Dutilh and

Wacksmuth in Philadelphia from Pittsburgh, Allentown, and Bucks Countythat concern the Black uprising in St. Domingue and aiding his friends there,” MSC 156:Mercer Museum Research Library, Bucks County Historical Society, Doylestown, PA.; “An Act To Incorporate A Society By The Name Of The Pennsylvania Society For Promoting The Abolition Of Slavery And For The Relief Of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held In Bondage And For Improving The Condition Of The African Race,”The Statutes at Large of Pennsylvania from 1682 to 1801(Harrisburg: Harrisburg Publishing, 1908), 13: 424.

[27]Kilbourne, Virtutis Praemium, 1007; Pennsylvania, Wills and Probate Records, 1683–1993, Wills, No 300-349, 1857 [database on-line,https://search.ancestry.com/]. Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Original data: Pennsylvania County, District and Probate Courts. Thanks to Lewis Brett Smiler for locating these.

2 Comments

A highly engaging story about a truly committed revolutionary intertwined around so many seminal events! An amazing life story and I second your wish that he left a journal to fill in the blanks. With all those name changes, researching must have been very difficult!

I had always thought that Col Magaw did not elect to stay at Fort Washington but was ordered to hold the fort by Gen. Nathanael Greene and approved by Washington. With perfect hindsight, this decision is one of worst made by Continental Army officers as there was no strategic value in holding the isolated and what proved to be an indefensible position (as British ships proved they could sail past the fort with impunity).

What an amazing individual! Antoine might have even “out-Gumped” Forrest – Antoine’s story is true!