Few sea captains could claim they crossed bowsprits with Lord Nelson and sailed away – ship and cargo intact – but Nathaniel Carver of Plymouth, Massachusetts, was one who did. Not only did he survive the encounter, the American received a letter of commendation from the man who would later be remembered as the “Hero of Trafalgar.”

This unusual event occurred in the summer of 1782 just off Cape Cod. The outcome of the American Revolution was all but decided at this point. A year earlier, George Washington had forced the surrender of British forces under Lord Cornwallis at the Battle of Yorktown, and in April of 1782, peace negotiations had begun in Paris between England and its former American colonies.

Combat operations, however, had not ceased, though they were definitely on the down swing. On the ocean, smaller craft still needed to be careful that they did not sail into harm’s way, that is, any larger, armed vessels on the prowl for easy prizes.

On July 14, Carver was on a return voyage from North Carolina. The Plymouth captain was in command of the Harmony,a small schooner hauling corn from the southern states. Some reports identify his vessel as a fishing boat, which it may have been, but it is likely she was serving as a merchantman on this particular trip.

As luck would have it, Captain Carver’s schooner caught the attention of the HMS Albemarle, a twenty-eight-gun, sixth rate frigate under the command of none other than Horatio Nelson, then a junior officer in the Royal Navy. Nelson, a lieutenant, was on his way back to Quebec after a rather unsuccessful cruise to raid American shipping and to hunt for pesky privateers.

On this summer day, Nelson brought Carver onboard his vessel and ordered the American to serve as pilot through the treacherous shores in and around Cape Cod. Filled with shoals, sandbars and rock outcroppings, this notorious region is often referred to as the “Graveyard of the Atlantic” – and for good reason. Over the past 500 years, the complex coastline along Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket has claimed thousands of shipwrecks.

Which is precisely why Carver was such a valuable asset to Nelson. The American captain’s knowledge of the local waters would be extremely helpful as the Albemarle continued its mission in the seas off New England.

Undoubtedly, Captain Carver was aware of the capabilities of his captor. The British lieutenant had scored several small successes as a captain of tenders and also as master and commander of the HMS Badger, a brig with twelve guns.

Of course, this was not the Nelson of legend that Carver encountered. He was not yet a lord, nor even an admiral. Horatio Nelson was only twenty-three and captaining only his second ship. Ahead of him still lay fame and glory. This remarkable leader with a unique understanding of strategy and the ability to create unconventional tactics in in the heat of bloody conflicts was just beginning his march into history.

Nelson would go on to become one of Britain’s most famous naval war heroes. His presence of command in battle resulted in several decisive victories for England and cemented the notion that “Britannia rules the waves.” And he was not afraid to put his own life on the line. Nelson lost sight in his right eye in combat off the island of Corsica in 1794 and most of his right arm in a rare defeat in the Canary Islands in 1797.

At the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801, then-Vice Admiral Nelson was leading his ships into battle against a formidable fleet of Danes and Norwegians. The British flagship signaled for him to retreat but Nelson put his telescope to his blind eye and said, “I really do not see the signal!” He then resumed the battle and led Britain to victory. Thus, “turning a blind eye” entered the English lexicon.

Nelson would go on to strike fear into the French fleet during the Napoleonic Wars. His boldness and aggressive attacks decimated the enemy and resulted in major naval triumphs for England. His crowning moment came at Trafalgar in 1805, when the Royal Navy crushed the French fleet and ended Napoleon’s dream of conquering the British Isles. At the beginning of the battle, Nelson sent a stirring signal to his ships: “England expects that every man will do his duty.” Ever since, this stalwart expression has been the country’s motto during times of duress.

Trafalgar was also the end of Nelson. He was mortally wounded by a sharpshooter as his flagship, the famed HMS Victory, moved in to deliver a death-dealing broadside to a French vessel. Nelson was buried with full honors at a state funeral. Today, his likeness stands atop the Nelson Column at Trafalgar Square in Westminster to remember his heroic sacrifice.

However, that was all in the future. In 1782, Nelson was just coming of age. And now, with Captain Carver serving as an able pilot, he was able to continue his raid.

For the next month, Nelson had Carver help him navigate the bays – Boston, Massachusetts and Cape Cod – while the Albemarle harassed American merchantmen and challenged the French fleet in Boston Harbor to sail forth and do battle. Under the command of Louis-Philippe de Vaudreuil, the French ships finally took notice of this upstart Englishman and began the hunt.

With Carver’s assistance, Nelson led four French ships of the line and a frigate on a merry chase from Boston Harbor, around Cape Cod, and down to Vineyard Sound. Rather than fleeing his enemy, the English lieutenant was trying to induce a mistake by the French admiral so he could lessen the stacked odds against him and make it a fair fight.

Captain Carver’s local knowledge proved advantageous. The American was able to direct Nelson through a series of shoals where the deeper-draft French ships dared not follow. Once past these hazards, Nelson noticed the French flagship had become separated from the rest of the fleet. The English lieutenant ordered his crew to shorten sail and came about to engage the enemy. The French admiral – even with at least 40 more cannon – thought better of the situation and made a tactical retreat.

Following this event, Nelson sailed the Albemarle back to Plymouth and returned Carver and his crew to their homeport. The English lieutenant kept the Harmony to serve as a tender. Carver reported the incident to the schooner’s owner, Thomas Davis of Plymouth, who was determined to recover his vessel.

Davis loaded fresh meats and provisionsonanother boat, and then he and Carver sailed out to meet Nelson. They pulled alongside the Albemarle and shouted that they had brought the lieutenant a gift. Nelson welcomed them aboard. He was pleased to receive fresh food and vegetables since he had been at sea for several months and was in desperate need of resupply, especially with the ever-present threat of scurvy hanging overhead.

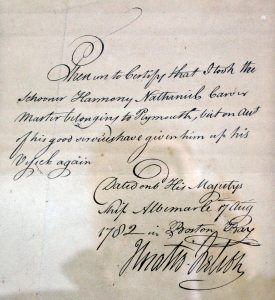

Nelson invited Davis and Carver to join him for dinner in the captain’s quarters. Not a word was spoken about the return of the ship. Following the meal, the lieutenant called for his writing desk and wrote the following certificate (spelling and punctuation appear as on the actual manuscript):

These are to certify that I took the schooner Harmony Nathaniel Carver master belonging to Plymouth, but on acct of his good services have given him up his vessel again.

Dated onb His Majestys Ship Albemarle 17 August, 1782, in Boston Bay

Horatio Nelson

The letter was a “Get out of Jail” card for Davis and Carver. It guaranteed the Harmony would not be troubled during any future encounters with the Royal Navy. Nelson then handed over the certificate and released the schooner back to the possession of its owner and master.

The Davis family kept the letter. Immediately after the American Revolution, it was seen as a novelty – a kind of a war souvenir from a quirky moment between two warring nations. However, it soon became a prized possession as Nelson’s acclaim began to rise.

The certificate was passed through the family for generations, eventually being framed and hanging prominently on the wall for all to see. For some time, it was believed to be the only signature of Nelson in the United States.

The certificate was unknown in England until 1852, when Abbott Lawrence, minister to the Court of St. James, happened to mention it in conversation with a professor of history at the University of Edinburgh. The professor was astounded because he was unaware Nelson had served in North America during the Revolution. He did not believe the story until a copy of the certificate was later presented.

William T. Davis, the great-grandson of Thomas Davis, eventually came to own the letter and wrote about it in one of his many history books about Plymouth. The Davis descendant was clearly proud of his family’s legacy and even shared the story with British historian Robert Southey, who included the event in “The Life of Nelson,” the first definitive biography of the admiral, which was published in 1886.

The whereabouts of the original certificate is unknown today but is believed to still be in the possession of the Davis family. A facsimile resides at the Hedge House, headquarters of the Plymouth Antiquarian Society in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Replete with remarkable penmanship and the flourishes of the later First Viscount Nelson, First Duke of Bronté, it is a fascinating link to a nearly forgotten moment of the American Revolution – a brief encounter when hostilities were temporarily suspended and enemies could treat each other with respect.

References

William T. Davis History of the Town of Plymouth with a Sketch of the Origin and Growth of Separatism(Philadelphia: J.W. Lewis & Co., 1885).

Biographical Review Containing Life Sketches of Leading Citizens of Plymouth County, Massachusetts(Boston: Biographical Review Publishing Company, 1897).

Representative Men and Old Families of Southeastern Massachusetts(Chicago: J.H. Beers & Co., 1912).

Sir Harris Nicolas, ed.,The Despatches and Letters of Admiral Lord Viscount Nelsonedited by (London: Henry Colburn, Publisher, 1845).

Edwin L. Miller, ed., Robert Southey’s Life of Nelsonedited by (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1898).

7 Comments

Very interesting. By chance do you have the ships list of Nelson’s crew? Suspect my husband’s 6th great grandfather may have been on ship with him.

If so, a great deal of his family lore will be further verified.

The muster books for HMS Albemarle from 1 February 1781 thru 31 July 1783, the only books that survive from this era, are in the National Archives of Great Britain, cataloged as ADM 36/10080, 10081 and 10082. These documents list every person who was on board the ship. Only the original manuscripts exist; they have not been digitized or microfilmed; as such, getting information from them requires visiting the archives in person or hiring a researcher to do the work for you.

http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/

David, thank you for this article and a valuable look at the “Nelson certificate,” which I have not seen in other material pertaining to Nelson. One correction, if I may: Horatio Nelson was promoted to post-captain in June of 1779, at the age of 20 (John Sugden, Nelson: A Dream of Glory 1758-1797, pp 141-142) so he was a captain when he commanded the Albemarle. The fact does not diminish either his accomplishments or your article, however!

To follow up on Don’s point regarding the British National Archives, I have had two occasions to call on them via the internet in the past year and they have been very helpful. You can do as Don suggests, or if you have a reasonable starting point, give the archives that information and for a modest fee (around $10) they will do a search and tell what is there and, if successful, how much it would cost to digitize and email the information to you. That second cost is so much per page and is not a deal breaker.

The website can take a little time to negotiate, but there is a ton of information there. To send you inquiry, try this link: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact-us/make-a-records-and-research-enquiry/make-a-records-and-research-enquiry-form/

David,

Thank you for this insightful article. As a maritime historian I always enjoy nautical articles especially when the setting was southern New England waters where I have boated for many years.

Dan Hazard

Interesting article on a distant relative. Captain Carver’s aunt Hannah (Carver) Shurtleff was my sixth great grandmother.Thank you for the article that caused me to dig further into my heritage and get the Descendants of Robert Carver of Marshfield, Mass. book on hathitrust; which relates this story on p. 82-83.

Thank you for the very interesting article. Don mentioned the ship muster books in ADM 36 at Kew. I this morning received images of them for this time period concerning prisoners taken by Albemarle. The books show “fishing boats” taken on July 13th, August 12th, 13th & 16th. All the men were released “at sea” on September 3rd. Carver’s name however is not mentioned among them however, nor are any of the fishing boats’ names.