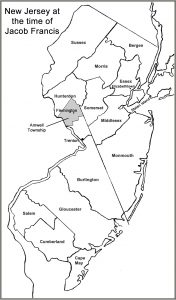

When Jacob Francis[1] began life on January 15, 1754 in western New Jersey’s Amwell Township in Hunterdon County, free black people in a state supporting slavery could find life unpleasant unless they “knew their place.” During his long life, Jacob not only fought for the concept of freedom and independence from Great Britain in the American Revolution, but also experienced varying degrees of personal freedom during the early phases in the struggle for racial equality within American society.

To provide necessary farm labor, New Jersey farmers at times utilized family, neighbors, hired help, indentured servants, and slaves. The rate of indentured servitude began to increase in Hunterdon County about the middle of the eighteenth century and Jacob’s free black mother, name unknown, indentured her young son until age twenty-one to a local German-born farmer, Henry Wambaugh, owner of a 106 acre farm in Amwell.[2] Jacob’s “time” was sold and purchased by a succession of men, including Joseph Saxton who took him as his servant to New York, then to the island of St. John in the Caribbean, and finally Salem, Massachusetts. Saxton sold Jacob’s remaining time to Benjamin Deacon of Salem with whom he lived until his time “was out” in January 1775. Jacob remained in Salem and worked for a succession of people as the Revolution heated up with the engagements at Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill.

Towards the end of October, he enlisted at Cambridge as Jacob Gulick/Hulick in Capt. John Wiley’s[3] Company of Col. Paul Dudley Sargent’s 16th Continental Regiment. Not knowing his family surname, Jacob used the name of his third “time” owner, Minne Gulick or Hulick, an Amwell farmer of Dutch ancestry. However he felt about the ideals of liberty and independence driving the Revolution, as a free black who had experienced indentured servitude most of his life, he probably enlisted at least partly because he was a young man accustomed to authority, who needed a job, and who may also have been seeking adventure. When approaching the recruiting officer, though, he found that free blacks were not encouraged to enlist and often not accepted.

From the time Washington took command at Cambridge, he wanted to exclude black men from the army. Washington interpreted the fact that there already were “boys, deserters, & negroes” in the Massachusetts regiments as proof that not enough qualified white men were enlisting. At the very time Jacob enlisted in October, Washington was discussing with his officers and Congress whether or not blacks should be enlisted and, while not unanimous, most leaders wanted to eliminate black enlistment entirely. By October 31, just days after Jacob’s enlistment, Washington’s general orders stated that blacks should not be enlisted and this order was reinforced in November. However, by the end of December, Washington gave permission to officers recruiting for the 1776 one-year Continental Army to re-enlist free blacks, at least temporarily until he obtained the concurrence of Congress, which he got on January 16, 1776. Washington made this modification out of concern that not nearly enough white men were enlisting and fear that free blacks would join with the British, in reaction to Lord Dunmore’s proclamation in November, if not accepted by the Continentals.[4] Within days of Jacob’s enlistment, General William Heath wrote to John Adams from camp at Cambridge that, “There are in the Massachusetts Regiments some few lads and old men, and in several regiments, some negroes.”[5] So, when Jacob enlisted there was no guarantee that he would not be discharged just because of his race and he joined an organization that would have preferred a white man instead. He was accepted only because he was a badly needed body.

After the British evacuated Boston, Jacob’s regiment was ordered, about harvest time, to New York by way of New London and by August 27 was at the northern end of Manhattan Island at Horn’s Hook, opposite Hell’s Gate, where the men constructed breastworks.[6] Part of the regiment, including Captain Wiley’s company, was sent to Long Island after the August 27 battle there, to remove cattle and horses, but they were forced to retreat back to Hell’s Gate with the loss of one man captured from Wiley’s company. They were in several firefights and on September 18 marched by way of Kingsbridge to West Chester, where, as Jacob said, “We lay there some time, and every night we had a guard stationed out two or three miles from where the regiment lay at a place called Morrisania. I mounted guard there every time it came to my turn.”[7] The regiment did guard duty on Throggs Neck where the British threatened to land and on October 22 set out for White Plains where the Battle of White Plains took place on the 28th. After a day of fighting the British for possession of a hill, Wiley’s company retreated back to camp where Jacob “stood centinel that night in a thicket between the American camp and the hill so near the British lines that I could hear the Hessians in the garrison which was between ¼ & ½ mile from me.”

After White Plains, Sargent’s regiment was assigned to Gen. Charles Lee’s division left in New York to guard against a British invasion of New England. However, if the British sent strong forces into New Jersey, he was to support Washington there. Lee famously did not join up with Washington, ignoring several orders to do so, and only after Lee was captured on December 13, and John Sullivan replaced him, did the regiment join Washington in Bucks County on December 23. On December 24 the men were drawing cartridges and provisions in preparation for a “scout.”[8]

On the night of December 25 Jacob crossed with Washington’s army at McKonkey’s Ferry, as part of Sullivan’s Division that during the march to Trenton split off from Greene’s Division and took the River Road. He entered Trenton on its southwest side and “marched down the street from the river road into the town to the corner where it crosses the street running out towards the Scotch road.” This was King Street where much of the early action took place, putting the Hessians between Sargent and Washington. After about half an hour of fighting in the wind, sleet, and snow, Jacob recalled, “the firing ceased & some officers, among whom I recollect was General Lord Stirling, rode up to Col. Sargent & conversed with him then we were ordered to follow.” They marched toward the stone bridge across the Assunpink Creek that provided a potential escape route for the Hessians. After helping secure the bridge they crossed it and spread out along the Assunpink to prevent Hessians from wading through the creek to escape the town. There, Jacob stated, “we were formed in line and in view of the Hessians, who were paraded … and grounded their arms and left them there.” This was the surrender of the Knyphausen Regiment, the final act of the Battle of Trenton.

With the battle over, Washington wanted to get his nearly 1000 Hessian prisoners across the river to Bucks County and Jacob was one of the men detached from his regiment to escort some of them down to the Trenton Ferry. About noon it began to rain very hard and he recalled, “We were engaged all the afternoon ferrying them across til it was quite dark when we quit.” That night, Jacob slept “in an old mill house above the ferry on Pennsylvania side.” The rest of the army and prisoners, still in New Jersey, marched back all the way to Johnson’s Ferry to cross back to Pennsylvania. Sargent’s regiment did not get back across until the next morning. Only partially successful at Trenton, Washington wanted to find a way to make the British retreat from more of New Jersey and, after resting his troops, decided to cross back to Trenton. On December 30 Jacob crossed the Delaware again, this time at Howell’s Ferry between Trenton and Johnson’s Ferry.[9]

The enlistments of Jacob and the other men in his regiment expired at the end of the year, so he was among the many men whom Washington tried to convince to voluntarily extend their service for a few weeks. Even though black re-enlistment rates were strong during the war and he did not express any dissatisfaction with army life in his pension application, Jacob did not extend his, even for the $10 bounty Washington offered. He had been in the army for fourteen months and was owed seven and a half months pay. When verbally discharged, he was given only three months’ back pay and told to report to Peekskill, New York at a later date to receive the remainder and a written discharge. Jacob returned home to Amwell to search for his mother, whom he had not seen or communicated with for many years. He found her alive, but in ill health, and stayed with her, learning from her that his surname was Francis, but he never went to Peekskill to get his back-pay and discharge.[10]

Now that he was about twenty-three years old, Jacob set about trying to build a settled life for himself in a state that was struggling with its attitudes toward slavery and black people in general. He was an industrious young man and within three years owned a house and forty-six acres of land in Amwell. This was quite an accomplishment at that time for a young free black man and he was the only free black listed as owning land, and only one of two free blacks listed in the 1780 Amwell Township tax records.[11] Upon taking up residence in Amwell he was required by New Jersey law to sign into his local militia company commanded by Capt. Philip Snook, the brother-in-law of the first man who had purchased his time, Henry Wambaugh. As a fourteen-month veteran of the Continental army, Jacob brought much-needed military experience to his militia company and used it faithfully whenever called out for active duty. To prevent all men in a neighborhood from being out on active duty at the same time, each company was divided into classes and, depending on current needs, a certain number of classes were called out each month for a one-month tour and formed into composite companies containing men from several regular companies. The regiments would also become composites. So, while Jacob usually served under Captain Snook, there were times when he had a different captain.

Threats of British soldiers on Staten Island coming into New Jersey to forage for supplies or harass the Patriots created a constant need for western New Jersey men such as Jacob to be called out to defend eastern New Jersey. Jacob mentioned frequent tours at Elizabethtown, Newark, and other parts of East Jersey. Men were often called out every other month, making it very difficult to conduct other aspects of life, including keeping the economy going. Consequently, men often paid a fine or hired a substitute for a month tour when they felt they just could not afford the time away from home or job. On at least one occasion, Jacob was paid $75 to substitute for a man unable to go out.[12]

One time when Jacob was out near Elizabethtown his company encountered a British force and Jacob recalled, “The Hessians I think came foremost. There was three columns, blue coats, green coats, and red coats and, when they got on the rising ground, fired on us.” During the ensuing skirmish, Jacob and another man got separated from the company and were taken prisoner by a flanking party of Hessians. After passing through Newark with their prisoners, the British ran into an American militia ambush that “created some confusion and broke the ranks.” The four men guarding Jacob left him, allowing Jacob to step down a bank and lay down in some bushes until the soldiers left the area and he was able to get back to Captain Snook and his company.

On another tour his party ran into a larger number of British troops and had to retreat. He said, “I was behind the rest of our party, and a bullet struck very near me, upon which I suddenly turned round and fired. Then our whole party turned and fired on the British, upon which they retreated again. Our subaltern officers had pushed on ahead, and we saw no more of them. We marched on without them and joined the army at headquarters, and I joined my company.” In June 1778 he was out with Captain Snook at the Battle of Monmouth in a composite regiment commanded by Col. Joseph Phillips of the First Hunterdon Regiment. Jacob recalled, “Our regiment and myself with it was on the battleground and under arms all that day but stationed on a piece of ground a little to the northwest of where the heat of the battle was and were not actively engaged with the enemy.” However, Captain Snook “went in the course of the day for some purpose, but what I am unable to recollect or state, to another part of the field and received a wound from a musket shot through his thigh.”[13] One of his comrades from the militia, Moses Stout, recalled for the rest of his life that Jacob always called his knapsack a “Snap sack,” because that was what the New England troops with whom he had spent a year called it.[14]

In between militia tours and then after the war Jacob worked to establish his place in society while remaining a single man, until his thirty-fifth year in 1789 when he was ready to marry and start a family. He no longer owned land by 1784 and in 1789 he was living with farmer John Reid, who also owned a slave.[15] The woman he loved was a slave named Mary, one of several slaves, including ten or eleven-year-old Philis and adult Cato, belonging to prominent Amwell citizen Nathaniel Hunt. Cato was the former slave of “old Doctor Finley” and conducted local marriages between black people. As Mary Francis said in her pension application statement, “at the time of her marriage it was not customary for white persons to perform the marriage ceremony for people of coulor, but that so far as she knows it was always done by persons of their own coulor.” However, both white and black people attended the ceremony held at the home of her master. After the ceremony, Jacob purchased Mary and freed her. During their life together they had at least eight children, including seven boys.[16]

Although Jacob had faithfully served in the militia during the Revolution, the 1793 New Jersey militia law limited service to white men. There was no manpower shortage or severe military threat so the legislated restriction to white men was enforced, and even though he was still within the age range for the militia he was not part of it.[17]

About 1801, Jacob and Mary moved a short distance to Flemington where on March 2, 1805 Jacob satisfactorily gave a public account of his Christian experience as a prelude to being baptized into membership at the Flemington Baptist Church. However, a white parishioner accused Jacob of having cheated him in a transaction involving some rye, so he was not baptized that day. After the question about his honesty was resolved, Jacob and Mary were finally baptized and joined the church on May 11. Church records include the subsequent adult baptisms of several of their children.[18] 1802 and 1809 tax records show he was again a landowner, now owning 115 acres of improved land.[19] Asher Atkinson’s Flemington general store ledger contains notations of Francis family purchases made between 1809 and 1817, indicating they were an integral part of the community.[20] When Jacob had returned to Amwell after his Continental military service, the 1776 New Jersey constitution had inadvertently established voting rights that included women and free blacks. In 1807 the law was changed to deny the vote to free blacks, and also women.[21]

At the July 1826 Flemington celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, Jacob was one of just two blacks listed among forty-three “Revolutionary Soldiers” who wore “badges of broad white ribbon, stamped with the American Eagle, and the words and figures ‘Survivors of 1776,’ … affixed to the left button-hole of their coats.” During a procession of these men, a banner commemorating each of the major battles of the Revolution was carried by a veteran of that battle. However, Jacob did not carry the Trenton banner; that honor went to a man whose claim to service in the battle was shaky at best.[22] While the Francis family seems to have been well respected, at the time of this event celebrating freedom, a local leading voice calling for the colonization of free blacks back to Africa was Jacob’s own Baptist minister, Rev. Charles Bartolette, and at least one Hunterdon County man freed a slave whom he helped move to Africa, where he became a leading merchant in Liberia. Jacob’s family nonetheless remained active in the Baptist Church and his descendants continued to live in Flemington and Hunterdon County for many years.[23]

Jacob died on July 26, 1836 after dictating his will and leaving his entire estate to Mary during her life-time.[24] His obituary in the Hunterdon Gazette noted his thirty-year membership in the Baptist Church and that he had “raised a large family in a manner creditable to his judgment and his Christian character, and lived to see them doing well.” His military service was noted and also the respect that everyone had for him. It was particularly noted that “his fidelity and good conduct as a soldier were the subject of remark and received the approbation of his officers.”[25] His service in the Revolution was clearly something important to him as he navigated through the changing rights of, and conflicting attitudes toward, free blacks during his long lifetime. When Mary died on February 26, 1844 the only identifying information mentioned in her brief obituary notice was that she was a “colored woman” and died at an “advanced age.”[26]

[1] Unless otherwise noted, information in this article is from the pension file of Jacob Francis, NARA 804, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, W459. His statement is quite long and detailed. With only a few exceptions that will be noted, his statement is quite accurate. It provides a great example of a man who served throughout the war first in the Continental Army and then in his state militia. The pension file statement is corroborated by accompanying support statements as well as the pension files of Jacob’s friend Moses Stout, R10245 and a Massachusetts soldier from his regiment, David How, S29912. David How also kept a diary, Diary of David How, A private in Colonel Paul Dudley Sargent’s Regiment of the Massachusetts Line, Henry B. Dawson, ed. (Morrisania, NY: H.D. Houghton and Co., 1865).

[2] Hubert G. Schmidt, Rural Hunterdon: An Agricultural History (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1945), 248, 241. While there is no conclusive evidence that his mother was a free black, a search of the Amwell Township town meeting records shows no mention of an appropriate poor black woman needing assistance from the overseer of the poor or of the overseer arranging for the indenture of a black woman’s son. There are consistent yearly entries about the poor and only occasionally of an indenture. If his mother arranged his indenture, she must have been free since the son of a slave woman would have been the property of her master and after the indenture ran out he would have been a slave again if her master had indentured him out. Jacob was clearly a free man after his indenture and when he eventually returned to his mother he did not describe her as a slave. The records searched provide no clue as to the identity of his father.

[3] In his pension file statement, Jacob gave the captain’s name as Woolley, Worley, or Whorley.

[4] Charles Patrick Neimeyer, America Goes to War: A Social History of the Continental Army (New York: New York University Press, 1996), 72. Washington’s letters and general orders are in Philander D. Chase, ed., The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1985+), I: 90; II: 125, 188, 269, 354, 620.

[5] William Heath, camp at Cambridge, October 23, 1775 to John Adams, in Robert J. Taylor, ed., Papers of John Adams (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1979), III: 230-231.

[6] Confirmation of their location at Horn’s Hook at this time is found in: General Washington to the President of Congress, September 16, 1776, in Peter Force, ed., American Archives, 5th Series, II: 351.

[7] A Return of officers of the 16th Regiment was made at Kingsbridge on October 4, 1776, Force, American Archives, 5th Series, II: 874-875. See also: footnote on page 961 regarding an incident at Dobb’s Ferryand Orders to Colonel Sargent on October 9, 1776 on page 962, orders of October 10 on page 976, and General Heath to Colonel Sargent, October 14, 1776, on page 1036.

[8] How, Diary, 40. They called Throggs Neck “Frog’s Point.”

[9] In his pension file, Jacob states that he crossed at Howell’s Ferry on the night of December 25-26 for the battle of Trenton. This was a memory glitch in which he confused it with the crossing he made several days later when Sargent’s regiment apparently crossed back to Trenton at Howell’s. David How also said he crossed there. See How, Diary, 41. McKonkey’s and Johnson’s ferries crossed at the same location, McKonkey’s on the Pennsylvania side of the river and Johnson’s on the New Jersey side.

[10] David How also did not extend his enlistment and left for home on January 1, 1777 along with a number of men from Massachusetts, including most of the 14th Regiment, Marbleheaders who had helped with the crossing of the Delaware on the night of December 25-26. For more on the efforts to get men to extend see William L. Kidder, Crossroads of the Revolution: Trenton, 1774-1783 (Lawrenceville, NJ: The Knox Press, 2017), 166.

[11] Ken Stryker-Rhoda, “New Jersey Rateables: Amwell Township, January-February 1780 and June 1780,” Genealogical Magazine of New Jersey, Volume 47, Number 2, May 1972, 66-84.

[12] For a complete discussion of the New Jersey militia laws, how the system worked in actual practice, and how duty affected men’s lives, see Larry Kidder, A People Harassed and Exhausted: The story of a New Jersey Militia Regiment in the American Revolution (CreateSpace: 2013). Captain Snook’s Company was part of the Third Hunterdon County Militia Regiment.

[13] The tours of duty with Captain Snook are corroborated partly in other pension files, such as Matthias Abel S2028 and Jacob Johnson W796, and in New Jersey State Archives, Auditor’s Book B, pages 181, 185, 465. The wounding of Captain Snook by a bullet through the thigh is confirmed in New Jersey State Archives, New Jersey Adjutant General’s Office, Revolutionary War Manuscripts, New Jersey, Mss 6005 – a Certificate made out by Colonel Joseph Phillips accounting for expenditures during his three month recovery. More on the wounding of Captain Snook is found in the support affidavit of Jerome Waldron in Jacob Francis’ pension file W459.

[14] Moses Stout affidavit in Jacob Francis pension file W459.

[15] New Jersey State Archives, County Tax Rateables, Hunterdon County, Amwell Township, Book 867 1784 (he is a householder but no land), Book 868 1786 (he is not listed), Book 869 1789 (living with John Reid).

[16] A search of the incomplete Hunterdon County records relating to marriages and manumissions does not provide evidence of the sequence of events or their details. However, had he not freed her, their children born before 1804 would have been born into slavery rather than as free blacks.

[17] James S. Norton, New Jersey in 1783: An Abstract and Index to the 1793 Militia Census of the State of New Jersey (Salt Lake City: 1973), xvi.

[18] Hunterdon County Historical Society, Bound Mss 655, Records of the Flemington Baptist Church Organized June 19, 1798, as the Baptist Church of Amwell, from Jun 19, 1798 to November 11, 1867, copy for Hiram Deats, Flemington, NJ. The records show it was extremely rare for a potential member to be challenged as Jacob was.

[19] New Jersey State Archives, County Tax Rateables, Hunterdon County, Amwell Township, Book 870 1802, Book 871 1809.

[20] Hunterdon County Historical Society, Bound Mss 434, Ledger 1796-1807, Atkinson, Asher, General Store, Flemington, NJ. The ledger actually continues beyond 1807.

[21] Judith Van Buskirk, Standing in Their Own Light: African American Patriots in the American Revolution (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2017), 183. Marion T. Wright, “New Jersey Laws and the Negro” (1943). Faculty Reprints. Paper 221, dh.howard.edu/reprints/221, 19. Originally published in The Journal of Negro History, XXVIII, No. 2, April, 1943.

[22] “Celebration of the Jubilee, at Flemington,” Hunterdon Gazette and Farmer’s Advertiser, July 12, 1826, 26-28.

[23] Schmidt, Rural Hunterdon, 255.

[24] New Jersey State Archives, Hunterdon County Probate Records, Jacob Francis file 4303J, will and inventory 1836. The will is fairly long and provides something for each child. It also states how the estate should be divided after the death of Mary. He owned a house and lot and the inventory of the house contents indicates a modest middle class lifestyle.

[25] Hunterdon Gazette, Wednesday, August 3, 1836. The obituary also appeared in other papers, including the Cleveland, Ohio, The Cleveland Whig, August 16, 1836, 1.

[26] Hunterdon Gazette, Wednesday, February 28, 1844.

3 Comments

Very well done. Thank you.

Excellent article! And local to me to boot!

Hello,

Any information about where he is buried?

Thank you