Hidden in the Nineteenth Century histories of Georgia is a likely answer to a question that has puzzled students of the American Revolution in the South for decades; why was General Andrew Williamson, acting in the same manner as so many around him, singled out as a traitor, loathed by so many as the “Arnold of the South.”

From 1816 until 1883, the telling of the history of Georgia was largely dominated by three men, their work considered the benchmark by which other Georgia histories are compared.

As the thinking goes among those who know about these things, Hugh McCall was the first of these three earliest historians, and while fondly remembered is today considered the most flawed. William Bacon Stevens followed McCall, and with better source materials, has come to be viewed as a better historian than McCall. Charles C. Jones, jr., writing last, is considered by many as the best of the nineteenth century Georgia historians.[1] This is a proposition which, in my opinion, is flawed and does not always work well. Sometimes it takes all three, plus other non-Georgian historians, to get close to what must have been the real story.

Each wrote about a small, seemingly insignificant event that is, to me, an epiphany; a revelation into why the American Southern Strategy, following the Fall of Charleston, almost failed because of one man.

On the night of July 11, 1780, a group of desperate men crossed the Savannah River, escaping that part of Georgia left them like a bread crumb by the British. They were attempting to link up with rebel militia on the Carolina side. McCall wrote that this was the militia command – what remained of it—of Col. Elijah Clarke and that the crossing had been planned, “Agreeably to appointment …”

They had mustered on the North side of the Broad River, about six miles from where this river emptied into the Savannah, at Freeman’s Fort, one of the old forts in the area. Clarke, according to McCall, with one hundred and forty prepared men – “…well mounted and armed…” – made the crossing in the dead of night, at a private ford. Once on the South Carolina side, something happened. Men begin to have second thoughts and most of Clarke’s command, including Clarke, re-crossed the Savannah, to await a better time.[2]

Not everyone agreed with Clarke’s decision to make a second private crossing. “Colonel John Jones objected to the retreat,” and with a makeshift militia company of thirty-five continued into South Carolina. With Jones went John Freeman, one of the namesakes of Freeman’s Fort, and Stephen Heard, the next-in-line newly appointed Governor of Georgia.[3]

Forty-three years later, Stevens wrote a somewhat different, in the details, version of the same event. Clarke, according to Stevens, gathered at Freeman’s Fort with one hundred and fifty men. He planned to oppose the British on the South Carolina side of the river, but in a rather confusing way suggested that Clarke wanted to make “a determined stand” on the Georgia side, at Freemen’s Fort:

The attempt, however, of Colonel Clarke to make anything like a determined stand, at Freeman’s Fort, was unsuccessful; and most of his men, being discouraged, were dispersed to their homes, to await a more favorable time.[4]

Hidden in this small moment – a somewhat insignificant river crossing – is one starting point to a partial answer to a question that has plagued students of the Revolutionary War in the South for decades. The answer leads to why it became necessary for these soon-to-be Georgia refugees to abandon their families in Wilkes and Richmond Counties, to go great distance from their Georgia homes. Eventually the thirty-five who continued would join with other rebel militia, but not before half had been killed, wounded or exhausted by their ordeals.

The reason is found in what one man, Brig. Gen. Andrew Williamson, would do, in part because many around him had come to distrust him.

Stevens is more direct than McCall, writing that the reason these men had “rallied” at Freeman’s Fort was because of a failed promise by General Williamson – “that southern Arnold” – to come to their aid. “When his defection was known,” Clarke and his men were left with little choice but escape from Georgia.[5]

McCall, who has a better reason than Stevens to feel hard toward Williamson, makes no mention of the general’s part in why Clarke and his command crossed the Savannah. There is, however, a clue in something McCall wrote about the role Andrew Williamson played in the capture by the Cherokee four years earlier in 1776, of his father James McCall. He was of the opinion that Williamson’s friendship with a British agent, Alexander Cameron, contributed to his father’s suffering: “…this opinion was strengthened by the active part, afterwards taken by Williamson, in the royal cause.”[6]

Finally, a quarter century after Stevens wrote his history, Charles Colcock Jones, Jr. came close to tying it all together, meshing both McCall and Stevens into what is probably the best history of this night:

Maddened and chagrined at the traitorous act, and disappointed in his expectation of immediately taking the field against the British and Tories who, in large numbers, were running riot through various portions of South Carolina, he [Elijah Clarke] dismissed his command, granting leaves of absence and furloughs for twenty days that his officers and men might take leave of their families, arrange their affairs, and prepare for a long campaign. Freeman’s Fort in Elbert County was named as the point for the reassembling of this force. By the 11th of July, 1780, one hundred and forty men, strongly mounted and well armed rendezvoused at the designated place. Without waiting for further accessions, Colonel Clarke crossed his command by night at ford six miles above Petersburg.[7]

It is clear why Clarke would have been “maddened” at Williamson’s “traitorous act”, but why “Chagrined?” I suggest it was because Col. Elijah Clarke was one of those who helped put together what I am calling the American Southern Strategy, the response to Lord Cornwallis’ British Southern Strategy to conquer Georgia and the Carolinas. Clarke, aware of the Georgia modus operandi of the time – the wolf pack mentality that fed on their own wounded, powerful men engaged in destroying reputations, killing one another in duels and endlessly squabbling – probably thought this breakdown in a plan to help Georgia could have repercussions for him.

Caged now in Wilkes and Richmond Counties, the last anemic stronghold of rebel resistance, by the British moving up from Savannah and the lawlessness that came from Lord Cornwallis’ deliberate policy of letting settlers fight it out among themselves,[8] Clarke had to take care to cross the Savannah where he would not be observed, at a “private” place, and at night.

This private ford no longer exists, deep now under the reservoir behind the Richard B. Russel Dam. Before the river was reshaped by the dam, this crossing was at the end of Trotter’s Shoals, where the undulating bedrock of the Savannah River is often exposed in summer. At these times, the water current could be inches deep, flowing over numerous sink holes, sharp rocks, some as small as a fist, others bigger than a man, and treacherous ledges, with sand and loose gravel everywhere. It would have been foolish men who rode their horses, rather than walking, risking fragile legs, over this river bed in the dead of night. It must have been quite a sight to see: a group of men, probably in single file leading their horses, the last men coming down the Georgia side as the first man came up onto the South Carolina side, some 800 yards distant.[9]

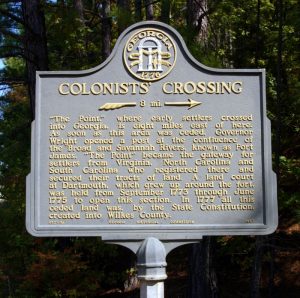

A little further down the river, and probably why this crossing was said to be “private,” is the much more public “Colonists’ Crossing,” the place where early settlers entered Georgia, at Fort James and the short-lived town of Dartmount, which became the not-much-longer lived Petersburg.[10] Ironically, the marker that currently identifies the site is closer to the “private crossing” than to the more “public” one.

Although thick underbrush covering steep slopes, woven into a mesh by stubborn vines, is characteristic of this part of the Savannah River basin, the banks of this “private crossing” were said to offer no difficulties.[11] Perhaps the ease with which the crossing was made had some small something to do with the men, now having second thoughts on the South Carolina side, deciding to turn back and re-cross the Savannah.

What faced them was the real reason most decided among themselves not to continue into South Carolina. Before them was an almost solid wall of British and Loyalists, in central and western South Carolina, mustering and training. On May 26, 1780, the same day Williamson left Augusta with what remained of his brigade to head home to Ninety-Six, Gen. Sir Henry Clinton had ordered Lt. Col. Nisbet Balfour to destroy the remaining militia under Williamson’s command.[12]

Williamson had remained in Augusta about as long as he could. On May 16, 1780, Williamson notified a “commanding officer” that he had “received official information” of the surrender of Charleston four days earlier.[13] Likely this commanding officer was his brother-in-law, Le Roy Hammond, stationed on the old Augusta-Savannah Trail near Spirit Creek, or John Twiggs who had been “requested” by Governor Richard Howley to “take post at this point.” [14] McCall wrote “The governor suspected that Williamson encouraged the delay of himself and his numerous train, that they might fall into the hands of the enemy. There were strong grounds to suspect that Williamson concealed his intelligence of the reduction of Charleston, several days after he was informed of that event.”[15] Capt. Matthew Patton presented a kinder view of Williamson’s actions from May 12 to May 16 than either McCall or Howley:

This despondent … was under the command of Major [Zachariah] Bullock of Col. [Christopher] Brandon’s Regiment and was stationed about 2 miles below Augusta in Georgia until a few days before the surrender of Charleston South Carolina on the 12th day of May 1780, when upon receiving the intelligence through Samuel Clowney of the communication with Charleston being cut off by the enemy, the companies stationed below Augusta were disbanded by General Williamson & remanded to their respective regiments making a term of three months service.”[16]

Samuel Clowney was a private in Captain Patton’s militia company and a boon companion, on occasion known to act alone, suggesting he may have been a scout or express who got advance notice, before the official notice, that something had happened at Charleston. He probably passed on this information to his friend, Patton.[17] Others would have soon heard.

At Augusta, Andrew Williamson, commanding the nucleus of the town’s defenses, was under tremendous pressure from his officers and men to return to South Carolina. Joshua Spears, in his pension application, told something of the tension that existed among the South Carolina militia.

At the expiration of the 3 months (in the month of May) the term for which the Regiment under Colonel [Matthew] Singleton was drafted – the Colonel (Singleton) requested of the General the discharge of his Regiment. Instead of discharging the Regiment the General (Williamson) had Colonel Singleton placed under arrest and his sword taken from him. The Regiment being highly irritated and their term of service having expired marched off without a discharge, and reached their homes in May….General Williamson was odious to the soldiers from the then suspicions of his Toryism which were afterwards confirmed – and the Regiment marched off without a discharge.[18]

Private Spears also did not like the fact Williamson “had his washing done at the house of a Tory on the other side of the River” – in South Carolina” – something Spears and others in the regiment suspected would have permitted the General to have “had correspondence with the enemy.”[19]

Georgia, to me, was the place where rebel generals went to have their reputations tarnished or even shattered: Maj. Gen. Robert Howe, like Williamson accused of “collusion with the enemy;” Maj. Gen. John Ashe, with some justification but not solely, exonerated of the charge of cowardice, but censured and disgraced for his lack of foresight at Briar Creek;[20] now Brig Gen. Andrew Williamson, on the edge of suspected betrayal, destined to become the “Arnold of the South.”

Despite pressure from his brigade, Williamson sometime between May 16 and May 26, 1780 called a council of officers to meet for what seemed to be the purpose of discussing what should next be done. Present at this council was a most extraordinary gathering of men. To be a seed of such monumental consequence, it is frustrating how little attention this meeting has been given by historians. Almost nothing is known about it. It is in Johnson’s Traditions that we find the better clues as to who attended:

On being notified of the surrender of Charleston, these troops were notified that the enterprise was given up, and a council of the officers called, to meet the next day, at McLeans’ Avenue, near Augusta, to consult what plan might be most advisable to adopt for the good of the country. Colonel Clary, with all the officers of his command, attended; Governor Howley, of Georgia, his council, his secretary of state; Colonel Dooly, and several other militia and continental officers of the Georgia line; General Williamson and suite, with a number of field officers of his brigade, also attended. General Williamson presented a copy of the convention entered into by the American and British commanders, at Charleston, which was read by one of Governor Howley’s secretaries. Various plans were proposed and discussed, but finally no plan of operation could be resolved upon. Governor Howley, his council, secretary of state, and a few officers of his militia, determined to retreat, with such of the State papers as could be carried off conveniently towards the North.” [21]

Nothing is mentioned of Col. John Twiggs being present, but he was nearby and, as Samuel Hammond and likely his uncle Le Roy Hammond attended, it must be considered that Twiggs was there also. Peter Deveaux, aide to Howley, in a correspondence involving Hugh McCall, would “certify” that he was also present;[22] I am convinced that Deveaux is one of the sources used by McCall to write this part of his History of Georgia.

Steven Heard was there as part of Howley’s executive council. Heard, nine months later on March 2, 1781, was the first to say something about what came about at this meeting, writing a report to the in-exile Howley:

After your Departor from Georgia General Williamson in a few Days Retreated from Augusta to his own Plantation Nier Ninty Six. They Council Thought Proper to Adjourn to Wilkes County and Join Camp Expecting to Act occationly with the South Carolineans to Defend the Uper parts of Both States till Assistance Could be Sent to our Relief, But to our grate Surprize Williamson and part of his Bragaed [Brigade] Capitulated with a Capt Paris that Imbodied they Torys on [illegible].”[23]

Here, in plain sight, was the Patriot Southern Strategy. Williamson would come back from Ninety-Six, commanding the core of a new militia army, one that would keep the British out of the “upper parts of Both States till Assistance Could be Sent.” Although Samuel Hammond wrote that the meeting ended with “nothing conclusive adopted for defense,”[24] it is almost certain the surrender of Andrew Williamson was off the table.

Ten days later, upon returning to Ninety Six with what remained of his Augusta command, Williamson sent a letter “To the Officer Commanding the British Troops on the North Side of Saludy River.”

Sir

… being desirous on my part to prevent the effusion of blood and the ruin of the country, I send the bearers, Major John Bowie, Richard A Rapley and James Moore Esquires, and request you will inform them of the tenor of the powers you are invested with.[25]

On June 10, 1780, with generous terms before him, Williamson surrendered his South Carolina command and took a British parole. Among those signing the “Articles of capitulation, Fort Rutledge and south side of Saluda” was Maj. John Bowie “on behalf of the people.”[26]

In the minds of many, Williamson’s betrayal was a fait accompli, an accomplished fact, leaving men like Col. Elijah Clarke to eventually pace forth and back across a river, trapped like caged animals, unsure what to do next, with few choices remaining.

There remain big holes in this story; many paths of discovery are still there. Agreeing to surrender “on behalf of the people” was Maj. John Bowie, who likely was present at the Augusta Council and a witness to how difficult – impossible, really – it became for Williamson to convince his South Carolina militia to continue the fight. There is more to the story of why Bowie finally had nothing more to do with Williamson and became an aide-de-camp to Andrew Pickens. What Bowie had to say does not bode well for Williamson, but I am suspect of Bowie also. Good friends, Williamson and Bowie often dined together, apparently at times with Pickens. At a last dinner, following an ill-advised toast to the King offered by Williamson, an angry Bowie and heart-broken Williamson parted company, never to see one another again.[27] Williamson, said Bowie,

…had gone too far to recede; and to the day of his death, I have no doubt, sorely lamented the fatal step he had taken … my recollection is that Gen Williamson joined the British army, and never again associated with his old friends in the upper country.”[28]

As always with anything to do with Williamson, there is a different interpretation to what took place at this dinner party.

Across the Savannah, back at Ninety-Six, there came a subtle shift in the historical account: “The Brigadier could continue the war or he could surrender. Upon the approach of Colonel Innes he had to make his decision.”[29]

In Georgia, there was no discussion of Williamson’s possible surrender. In South Carolina, surrender became something that must be considered as the British took control of towns, roads, and river crossings. Loyalists in numbers, four days before Clarke crossed and re-crossed the Savannah, had flocked into Ninety-Six, strangling the backcountry. In one afternoon, six new Loyalist regiments were formed.[30] Likely this is the something that caused Clarke’s men to turn back.

Among the more damaging claims against Williamson are those coming from Andrew Pickens, who I find strangely silent, complicit and noncommittal – although this was his nature – during the time this decision to fight or surrender had to be made. Pickens suspected as early as the Battle of Kettle Creek, a year and a half before Williamson called for the Augusta Council, that Williamson was beginning to lean toward the British. Pickens would write that it was at Augusta “I believe Williamson was corrupted.” Pickens found Williamson’s lack of aggression, failing to act against the British “all this time opposite each other at Augusta” suspicious.[31] Private Spears, who thought his general “odious” also noted how inactive Williamson had been: “Nothing was ever done by the Americans as long as deponent remained in the camps, except some straggling Tories were occasionally taken on the other side of the River in Georgia.”[32]

Some indication of the difficulty Williamson had with his men at Augusta, and perhaps part of the explanation as to why he failed, upon returning to South Carolina, to persuade his brigade to follow him into North Carolina to regroup and return, can be found in something else Spears said:

That General Ash [sic, John Ashe] had but a short time before on Brier Creek had his whole Corps dispersed by the British and Tories, and designedly as was generally believed by our Regiment – and that it was the intention of General Williamson to lead his troops to a similar defeat.

Spears went on to state that he had often heard his colonel, Matthew Singleton, “pronounce General Williamson a Tory.” Taking Private Spears and Colonel Singleton with a grain of salt, there may be something to what they said.

Williamson did not have the trust of his command. This is not yet a solid conclusion, but in my study of a healthy number of the more than 400 pension applications of the old veterans who served under Williamson, I have come to see a certain pattern. More than just Spears and Patton thought he betrayed them at Augusta. I have, to this point, found no one who served with him, other than Gen. Richard Richardson, who had anything good to say. Because the pension application process required it, most noted simply something like “Gen Williamson commanded.”[33] Yet when old vets, in some number, spoke of their old commanders, generally you will find one or two who expressed warmth or regard.

It may be that this view of their general being in sympathy with the British spread over the years, coming to infest how his men remembered him. In turn, this would influence the earliest Georgia historians who used these old vets as sources. William Dawson, like Spears and Singleton, was part of Williamson’s brigade at Augusta. After the war, he continued to live in Edgefield District, across the Savannah River from Augusta. He stated in his pension application, “The applicant was at the defeat of the Army of General Ash (which was a detachment from General Williamson’s Army) at Brier Creek in Georgia in March 1779.”[34] Can this be seen as a criticism of Williamson, a failure to come to the aid of Ash?

Dawson was an eyewitness on the day Williamson spoke to his assembled command, and the decision to surrender was made: “General Williamson acted treasonously to his Country & obtained possession of all of the strong parts in the interior & up country of South Carolina, surrendered all the men (whom he could) under his command near Cambridge [Ninety Six]– the applicant having been paroled remained in this situation till the fall of the same year, when he volunteered in the service and joined an Expedition under the command of General Elijah Clarke.”[35] Someone had second thoughts about putting such a comment in a pension application and a strike through was made in Dawson’s application.

It is not known if Dawson was among the small number of men – about five or six – who raised their hands, voting to not surrender when Williamson put the question of what to do before his assembled command.[36] Perhaps, over the years and the telling and retelling of that day, sharing memories with others who had been in the war, the seventy-four-year-old Dawson came to see himself in a different light than when he was twenty-two.

Using different nineteenth century sources, a dissimilar story of Andrew Williamson, less a traitor than presented in these early histories of Georgia, could be written; perhaps he is a peacemaker, truly intent on preventing “the effusion of blood and the ruin of the country,” or a war profiteer with an uncommon love of money; maybe he is a lucky genius who knew how to survive with his family and fortune intact, or a backcountry behind-the-scenes advisor with skills needed by men like Lord Cornwallis, British Colonels Balfour and Innes, and later, at Charleston, Patriot Gen. Nathaniel Greene and American spy master John Laurens. Ian Saberton, who knows well the British view of Williamson, suggested he was a man of “duplicitous approach,” someone trying to remain “peaceably at home, doing whatever little was necessary to achieve this end.”[37] Possibly he was all these.

When you get to Charleston, where the Williamson family appeared to suffer none of the stigma that surely would come with being a traitor, Williamson’s “crime” seemed to be that he acted in a manner unbecoming a married man,[38] never mind he had been a widower for several years. Historian Logan simply let John Bowie tell the story, but made sure we know the daughters of Andrew Williamson were remembered as moving smoothly through Charleston society, making good strategic marriages.[39]

At this point it is not yet time to submit all this to a jury. All I am willing to conclude, at the moment, is that at a council in Augusta, immediately following the Fall of Charleston, Andrew Williamson appeared to pledge not to surrender and seemingly agreed to become the key that would unlock the American Southern Strategy. He surrendered, and was seen by those who heard him as betraying this pledge.

[1]John C. Inscoe, “Hugh McCall (1767-1824).” New Georgia Encyclopedia, www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/, accessed October 25, 2017.

[2] Hugh McCall, The History of Georgia (1811, 1816; reprint, Atlanta: A. B. Caldwell, 1909), 473.

[3] McCall, History of Georgia, 474.

[4] William Bacon Stevens, A history of Georgia: from its first discovery by Europeans to the adoption of the present constitution in MDCCXCVIII (New York : D. Appleton and Co., 1847-1859), 243.

[5] Stevens, A history of Georgia, 243.

[6] McCall, History of Georgia, 313.

[7] Charles C. Jones, Revolutionary Epoch History of Georgia, Volume II (Boston, New York, Houghton, Mifflin and company, 1883), 449.

[8] Ian Saberton, The Cornwallis Papers, Volume 1 (Uckfield, East Sussex: Naval & Military Press, 2010), 334.

[9] Sharyn Kane and Richard Keeton, Beneath These Waters (Savannah, GA: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 1994), 149: O.M. Carter, Annual Report of the Chief of Engineers, United States Army to the Secretary of War for the Year 1890, Part II (Government Printing Office, 1890), 1502.

[10] David Seibert, “Colonists’ Crossing Marker,” Georgia Historical Society/Commission Marker Series, www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=37051.

[11] W.P. Trowbridge, Statistics of Power and Machinery Employed in Manufactures, Part 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1885), 130. This Information was provided Trowbridge by James Edward Calhoun, who eventually comes to own this private crossing.

[12] Robert D. Bass, Ninety Six: The Struggle for the South Carolina Back Country (Lexington, SC: The Sandlapper Store, 1978), 184.

[13] Samuel Hammond Pension Application S21807, Southern Campaigns Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Roster, revwarapps.org. All subsequent pension applications are from this source.

[14]Jones, Revolutionary Epoch, 434.

[15] McCall, History, 470.

[16] Matthew Patton Pension Application S18153.

[17] Samuel Clowney (Clowny) Pension Application W9391.

[18] Joshua Spears Pension Application R9965.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Daniel W Barefoot, Touring NC Revolutionary War Sites (Winston-Salem, NC: John F Blair, 113), 113.

[21] Joseph Johnson, Traditions and Reminisces, Chiefly of the American Revolution (Charleston, SC: Walker and James, 1851), 149-150.

[22] Walter Lowrie, American State Papers: documents, legislative and executive of the Congress of the United States, Volume 9 (Washington, DC: Gales and Seaton, 1834), 599.

[23] Mary Bondurant Warren, Transcriber and Editor, Revolutionary Memoirs and Muster Rolls (Athens, GA; Heritage Papers, 1994), 123-124; Charles B. Baxley, Georgia Gov. Stephen Heard Letter, www.southerncampaign.org/2014/02/23/georgia-gov-stephen-heard-letter1.

[24] Samuel Hammond Pension Application S21807.

[25] Saberton, The Cornwallis Papers , 1: 115.

[26] Saberton, The Cornwallis Papers, 1: 97.

[27] John Henry Logan, A History of the Upper Country of South Carolina from the Earliest Period to the Close of the war of Independence, Vol II (Easley, SC: Southern Historical Press, 1980), 69.

[28] Logan, A History of the Upper Country of South Carolina, 72.

[29] Bass, Ninety Six, 189.

[30] Bass, Ninety Six, 194, 211.

[31] William R. Reynolds, jr, Andrew Pickens: South Carolina Patriot in the Revolutionary War (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2012), 133.

[32] Joshua Spears Pension Application R9965.

[33] Matthew Patton Pension Application S18153.

[34] William Dawson Pension Application S17920.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Johnson, Traditions, 151.

[37] Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, 77.

[38] Johnson, Traditions, 361.

[39] Logan, A History of the Upper Country of South Carolina, 56.

7 Comments

Definitely enjoyed your choice of subject matter. We rarely see much on these events but when one reads the pension files the importance becomes clear. The decision to give parole or continue the fight in the summer of 1780 was incredibly significant to each individual. Probably because each man made his own decision for his own reasons. I like to call the ones who went Patriot that summer the ‘Early Risers’. While men routinely mentioned battles in passing on their pension applications, they would often provide details as to their individual reasons for rising. Indeed, to have risen early enough to ride with John McClure or the leaders at Huck’s Defeat (July 12, 1780) was often worthy of a detailed description in spite of the battle itself being a very small affair.

Wayne–

As always, thanks for cutting through the stuff that get left behind in an article.

1. As for subject matter, I’m as confused myself as to why I become so fascinated by small, seemingly unimportant events– the choice of my subject matter. When asked why such little things, I fall back on the best childhood answer possible — “I don’t know.” I just like these smallest of occasions, like the one in the article; “envisioning” 140 men leading their horses across a great river, in the dead of night, in a summer dry spell, and back again within hours… Increasing desperate men, trapped, not sure what to do, crossing and re-crossing a river bed…What was going on?

2. As to pension applications: I am a firm vocal advocate for the work of Will Graves and Leon Harris. To me, the greatest untapped new sources for our better understanding are those 20,000 online pension statements. I’ve tried transcribing just one and it took me the better part of a morning; still never got it right. There are gold nuggets in that mine…

3. A comment about “early risers: that probably is the best box top three words or less answer to the point of my article. It was in Williamson’s destiny to become an “early riser” in 1780. Rising to meet the occasion is the true definition of leadership ( something we often confuse with great hair, good suits and a concerned look for our problems probably coming as a result of acid stomach.)

When Williamson was passed the baton, at Augusta, he failed to become an “early riser” in the summer of 1780. Thus begins his decline.

3.On the Savannah River… I see where the upcoming Williamsburg conference features James Kirby Martin making a presentation on “The River that Mattered Most in The Revolutionary War.” The agenda for the conference looks North, so maybe no one will be thinking about the backdoor river.

Look forward to when you put more thoughts about “early risers” into something we can read over morning coffee. Conner

Andrew Williamson is a fascinating character. The history on him is all over the place. I like Samuel Hammond’s accounts of the meeting at Augusta and White Hall. He has Williamson standing in the middle of four mounted regiments (formed in a square around him) arguing passionately for the brigade to remain in the field and continue the fight. Only in the face of refusal by his other officers and men did Williamson relent and decide to sign his parole. In that telling, Samuel Hammond and James McCall would be among a very few junior officers from the brigade to remain in the field. Apparently, Andrew Pickens made the same decision as Williamson, which was to give parole after having failed to convince his regiment to remain in the field. What Samuel leaves out is the role played by his uncle, Colonel Leroy Hammond. Also, who are these officers who voted so overwhelmingly against continuing the fight? Do we know who all they were? I believe that James Williams was one of the colonels from Williamson’s brigade but he also remained in the field.

Wayne–

When I gave up my first profession, upon retirement, and decided to do something easy that did not require much effort, allowing me to sit and sometimes think, I undertook a look at that most minor of effortless endeavors, history. Piece of cake. No controversy and with results as clean and clear as adding a row of numbers. Read a little, then jot down what you had read…that’s all it took, right?

About the time I realized this stuff was a lot like Quantum Mechanics in that now you see them, now you don’t, I met Charles Baxley, who like Williamson in only one respect, is all over the place. I mentioned to Charles a bit of frustration I was having over a minor engagement at Cedar Springs.

Charles suggested to me that a nice light beginners topic might be the life of Andrew Williamson. “There’s a big hole there in our understanding” he said. Three years later I have come to only one conclusion: Whatever someone says about Williamson, after sound detailed research can be countered pretty much by someone else who has relied on different sources.

We continue to get biographies on Pickens — how many now? Four? Eight? Sixty?–but not a single one on Andrew Williamson. Why? Recently Charles, who knows almost everything and certainly everyone, sent me something Will Graves had uncovered — the audited account of Andrew Williamson. It is a most remarkable document, a petition signed by many of the men, mostly officers, who had served with him UP TO 1780, and the point in time where he surrendered. After Will applied his skill and genius to transcribing it, I was able to see in great detail what was in the petition. The petition talks about Williamson having made a “political mistake” but not one so terrible that his family should pay the price of amercement. In my snail-like progress toward understanding this “big hole” I’m slowly, sitting in my rocking chair, coming to the conclusion that it might be best for us to stop calling him “the Arnold of the South” and perhaps view him as his contemporaries (most of them) did — a man who made a “political mistake.” The reason I’m not ready to make this leap is because of those darn Cornwallis letters that mention Williamson in such a way that it seems he was a behind-the-scene powerful architect of the British Southern Strategy when Cornwallis’ colonels get to Ninety Six.

My point is this: It will take a talented historian (hint), or a young promising graduate student under the guidance of a sound committee, with access to more than what is on the internet, to put the story of Williamson’s life together. You mentioned Samuel Hammond — nothing would please me more than to be present at a round table when that pension application is discussed. And then, as you observed, there is LeRoy Hammond…It’s time to put what we can discover about Brig Gen Andrew Williamson between bound covers.

A very interesting account of the life and death decisions made by the remaining patriot militia after the 1780 fall of Charleston. Clearly unsettled loyalties with dire consequences for the leaders’ actions. I wonder, however, if the comparison to “the Arnold of the the South” is truly appropriate. Arnold switched sides not just surrendered. Further, he attempted to give up a strategic fort. And most importantly he actively fought against his former colleagues. Lastly, Arnold had to flee to England never to return after the war.

Williamson only gave up. From this account he did not betray a fort, recruit and lead soldiers against the Patriots and continued to live in the US. Williamson’s actions appear to be more like RIchard Stockton than Arnold.

Here is a really good article on Williamson that showed up in the Journal of Backcountry Studies. I think that publication no longer operates but their articles are kept online at:

http://libjournal.uncg.edu/jbc/article/view/509/296

http://libjournal.uncg.edu/jbc/article/view/571/331

There is little doubt that the men from Georgia are being very hard on Williamson. He was clearly being offered the command position over all the Loyalist militia being formed in South Carolina. And, of course, he had much to thank the British for and much to risk in being a rebel. Andrew was likely the richest man in the back country districts around 96. He was mostly a self-made man without much education and yet his relationships with the British and his training with the British army had set him up for that success. Even with those motivations to become a Loyalist, it appears that Williamson never actually took any active role with the British. And certainly nothing that would compare him to Benedict Arnold. Let’s face it, Elijah Clarke (bless his Patriot heart) was really unhappy at the lack of communication from Williamson. He felt left out and I think Elijah did not anticipate that all the SC regiments would give parole the way they did. It caught Clarke by surprise and was made even worse by Williamson failing to send prompt notice back to Augusta. As a result, even though Clarke and his Refugees never waivered, they ended up taking the field about a month behind the Sumter and the partisans from the Fishing Creek area. The Georgians clearly blamed Williamson but it may be that he made an honest effort at keeping the 96 brigade in the field. Or at least Samuel Hammond says so. Others might not be so generous. I recently did a lecture on Williamson and the early risers. This quote went over well: One of Williamson’s friends came over for dinner one evening expecting to “meet only with a small party of particular friends. . . to my utter surprise and mortification, upon entering his parlor, I found it crowded with British officers in full uniform. A moment’s reflection determined me to submit to the exigencies of my position with the best grace I could command. After dinner, and after a very few glasses of wine, I arose from the table and took a respectful leave of the company; but after plainly evincing to the watchful eye of General Williamson my utter dissatisfaction with the whole affair.” Williamson himself had even given “the first toast, The KING!”

I have never been happy with the way John Bowie’s son tells that story about how his father and Andrew Williamson came to part. I could never see Major Bowie riding up to Whitehall and not noticing the Pickets, guards, grooms, horses, etc. and redcoat escorts that had to be all about the place. He says he expected Pickens to be present at the dinner, which is a clue to me that all involved — Williamson, Bowie and Pickens — were still honoring their paroles. I do think it was Williamson’s way of gauging if Bowie was ready to slide from parole to protection, and being pushed in front of these watchful red-coated officers was what offended Bowie so much.

I would give a wooden nickel to know who those British officers were at that dinner. I have long put the suggestion out there — totally unsupported for now–that Whitehall may have been the place senior British officers took up residence, in comfort, rather than remain at Ninety Six. The distance between the two is the problem; I need to show this may not have been all that common (Grant was 12 miles away, at breakfast, when he heard the cannons at the start of the Battle of Shiloh, but a different civil war is far from the “proof” I’m looking for…)

What happened to Williamson at Augusta was not unique. Augusta was the place to go, if you were a General, to see your reputation shattered. I agree totally with you that Williamson tried to keep his command together ( or did he? Was it all a sham, like how Pickens worked things around so he could break his parole?).

In that petition I mentioned where so many captains of militia companies, majors, Lts. and even a colonel or two, etc. seek to stop amercement of Williamson property, the most obvious omissions are the names of John Bowie, Andrew Pickens and Gervais Rappley and Mason sign, as does Col Wofford and Thomas. Perhaps that is because I was looking for them, but they were either not sought out or did not wish to sign when dozens who served with them, and Williamson, did sign. I beginning to wonder if this petition separated those who thought him a traitor and those who didn’t quite go that far…

In your assessment of Williamson as a man with a kind of Horatio Algier American Dream story, I have come to be suspicious of some of it — we all get the impression that he was a “lowly cattle driver,” but I’m starting to come across some stuff that suggests there may be more here than we first suspected. His father-in-law marries a woman (Third marriage for each. extremely complex) who was Catherine Williamson before she married anyone. She is something of a colonial aristocrat. I have often wondered how a “lowly man” (set aside he was wealthy–poof, like magic it appears– and that he was upcoming–the only back country man I can find who was commissioned into the lowcountry elite “silken” bluffs in the French and Indian War) became so acceptable to this branch of the Tyler family. But back country marriages weren’t always as strictly controlled, say, as they were in Charleston. How Williamson became so closely associated with Henry Laurens, moved so easily among Cornwallis’ senior officers, married into the family he did, had a secretary who went home to England and married a widow countess — the man is a contradiction.

There’s a good story here, waiting to be told.