As a British colony located on the Atlantic Ocean, Rhode Island’s wealth grew by utilizing the ocean’s vast resources. Rhode Island’s Narragansett Bay is roughly two hundred and fifty square miles, which includes small islands and bays. Hundreds of ships carrying both raw materials from the colonies and manufactured products from England traveled through Narragansett Bay annually. The port city of Newport was the maritime hub for the colony. During the time before the American Revolution the importation of molasses into Rhode Island was a large part of the local economy. Once imported, the molasses was distilled into rum and then exported. The colony had thirty-three rum distilleries operating at the time of the French and Indian War.

Parliament had attempted to generate revenue and regulate this trade within the North American colonies since the Molasses Act of 1733. The purpose of the Molasses Act was to protect the interest of British West Indies sugar plantations by taxing molasses imported from foreign competitors. The Act specifically targeted the importation of molasses from foreign sugar-producing islands in the Caribbean belonging to the French, Spanish and Dutch. It stipulated that,

There shall be raised, levied, collected, and paid, unto and for the Use of His Majesty, His Heirs, and Successors, upon all Rum or spirits of the Produce or Manufacture of any of the Colonies or Plantations in America, not in the Possession … all Molasses or Syrups of such Foreign Produce or Manufacture, as aforesaid, which shall be imported or brought into any of the said Colonies or Plantations of or belonging to His Majesty, the Sum of Six pence of like Money, for every Gallon there of.[1]

Smuggling foreign molasses became the norm, evading the six pence duty levied by the Molasses Act of 1733. This was due to lax enforcement, which meant Rhode Islanders made greater profits. Further encouraging smuggling was the law of supply and demand. It was not possible for Rhode Islanders to import sufficient quantities of molasses solely from British sugar colonies so foreign sources were necessary. Of the colony’s 14,000 hogsheads of molasses imported annually, only 2,500 hogsheads came from the tax-exempt British colonies.

The production of rum and the importation of molasses were key elements of the triangle trade. By 1750 Rhode Island merchants had a major share of the triangular trade, which worked by importing molasses from the Caribbean, distilling it into rum, bartering the rum for slaves in Africa, trading the slaves in the Caribbean for molasses and sugar, then finally returning to Newport to repeat the process. Some of the profits were then used to purchase manufactured goods from England.[2]

Following a decisive victory in the French and Indian War in 1763, Britain had a large national debt. In order to help pay off the debt, Parliament tasked the Royal Navy with enforcing the Molasses Act 1733. In October 1763, The Lords Commissioners of Trade and Plantations instructed the governor of Rhode Island “To make the suppression of the clandestine and prohibited trade with foreign nations” and also to “transmit such observations as occur to you, on the state of the illicit and contraband trade.”[3] It was clear the era of lax enforcement had ceased. A letter from Adm. Alexander Colville to the governor informed him that HMS Squirrel, a twenty-gun sixth rate vessel commanded by Capt. Richard Smith, was to be stationed in Newport during the approaching winter. In addition, the letter requested aid in the capture of any deserters from that vessel with the reward of forty shillings.[4] The stationing of a British warship within Narragansett Bay, in a somewhat permanent manner, must have been startling to the citizens of the colony who had enjoyed the luxury of unimpeded commerce for previous decades.

As enforcement commenced, the colony of Rhode Island sent a Remonstrance to the Lords Commissioners of Trade and Plantations, attempting to explain in a concise logical manner the devastation that would plague Rhode Island’s economy as a result of enforcing the Molasses Act. Their points of contention demonstrated how Rhode Island’s economy depended on commerce, especially the trade of foreign molasses. Unlike other colonies in North America, Rhode Island had no frontier to exploit or any staple commodity to export, making trade critical for economic survival. The Remonstrance explained the economic repercussions for implementing the Sugar Act:

There are upwards of thirty distil houses, (erected at a vast expense; the principal materials of which, are imported from Great Britain,) constantly employed in making rum from molasses. This distillery is the main hinge upon which the trade of the colony turns, and many hundreds of persons depend immediately upon it for a subsistence. These distil houses, for want of molasses, must be shut up, to the inulin of many families … and of our trade in general and as an end will be put to our commerce, the merchants cannot import any more British manufactures, nor will the people be able to pay for those they have already received.[5]

Rhode Islanders believed strict enforcement of the Molasses Act would not only hurt their economy, but was an attempt at impeding their rights.

In early June 1764, Admiral Colville dispatched four armed vessels to impress sailors between “Casco Bay and Cape Henlopen.”[6] Impressment was a way of offsetting the attrition of crewmen that was bound to occur on vessels that spent long periods on station away from Great Britain; the Royal Navy could forcibly take able-bodied seamen who were not currently at work. Instructions adopted in 1697 required captains to consult Colonial Governors for permission to impress, but that rarely happened. Impressment had occurred from time to time in North America throughout the century, but the increased navy presence made it a more frequent occurrence. The combination of revenue enforcement and increased impressment redoubled colonial resentment against the Royal Navy, which was beginning to disrupt the culture within the American colonies through all social classes, from the politician, to the merchant, to the average seamen.[7]

By mid-June, two Royal Navy vessels were in Rhode Island. They were not a welcome sight. HMS Squirrel and its tender, St. John, were tasked with enforcing the Molasses Act in Narragansett Bay. Before the month of June was over, Lieutenant Hill of the schooner St. John began seizing smuggled goods; “I forthwith made seizure of the cargo, which consisted of ninety-three hogsheads of sugar.”[8] With the colony’s long-established cultural norms suddenly challenged, it was inevitable that conflict erupted.

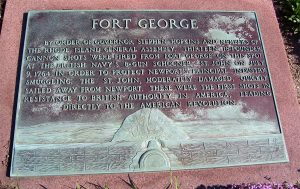

In July a small boat and armed crew, under the command of Mr. Doyle of the St. John, went ashore in Newport to retrieve a deserter from the vessel. When the sailors of the St. John reached the wharf, they were met by the deserter who was protected by an angry mob comprised of citizens who were apparently fed-up from harassment by customs officials. The citizens of Newport decided to take matters into their own hands and rioted against authorities. The St. John party was met with “Stones which fell as thick as hail round and in the boat.” Most of the crew was wounded and officer Doyle was taken prisoner. At this time, another boat from the St. John was sent to the Squirrel to inform the commanding officer of the situation unfolding. The orders from the Squirrel were, “To get under way and anchor close under her stern.” Seeing the St. John get underway prompted Rhode Islanders to give a proper Rouge Island farewell. The mob piled into a sloop and made their way to Fort George. Upon entering the fort that controlled the entire harbor, they began firing an eighteen-pound cannon at the St. John. A witness aboard the St. John recalled, “They fired eight shot at us, one of which, went through our mainsail, whilst we were turning out.” The St. John was forced to retreat to avoid any further damage.[9]

Outraged by the open acts of hostilities committed by the mob, Capt. John Smith of the Squirrel, in a letter to the Lord Council, questioned the legitimacy of Rhode Island’s government and the rebellious spirit of the citizens. In the following days, Smith went ashore to the fort and demanded justification for firing at the St. John. The fort’s gunner was questioned, who “produced an order for stopping that vessel, signed by two of the Council, the Deputy Governor being absent at that time.” After meeting with the Governor and Councilman, Captain Smith claimed that “I found them a set of very ignorant council.” The Governor claimed the gunner had the authority to act as he did and Rhode Island’s government answered for his actions. Captain Smith informed the Lord Council that the government and the citizens of Newport were working together to undermine the authority of the crown: “It appears to me, that they were guided by the mob, whose intentions were to murder the pilot, and destroy the vessel. But I hope it will, by Your Lordship’s representation, be the means of a change of government in this licentious republic.” No citizen of the colony was ever taken into custody for the crime. Firing cannons at the King’s ship a decade before the Battle of Lexington and Concord and the signing of the Declaration of Independence demonstrates the intensity of festering resentment within Rhode Island’s maritime communities. This action could arguably be labeled the first shots of the American Revolution.[10]

Instead of keeping the Molasses Act of 1733 in place, in order to increase revenue following the French and Indian War, Parliament passed the Sugar Act, which went into effect on September 30, 1764. This new act cut the six pence duty in half to three pence. To make up for lost revenue, additional duties were placed on coffee, silk, indigo, wines and other imported commodities.[11] Less than two weeks after the enactment of the Sugar Act, Rhode Island wrote a petition to the King to demonstrate how the people of New England endured many hardships when transforming the wilderness to a colonial settlement. The new duty put a burden upon commerce that would upset the cultural norms upon which the colony was built.

We will, with the most submissive sentiments, open our grievances, and humbly lay our complaints before Your Majesty. The restraints and burdens laid on the trade of these colonies, by a late act of Parliament, are such, as if continued, must ruin it. The commerce of this colony dependent ultimately on foreign molasses, and the duty on that being so much higher than it can possibly bear, must prevent its importation; and by that means we shall be deprived of our principal exports, totally lose our trade to Africa, and be rendered unable to make remittance to Great Britain for the manufactures we cannot live without.[12]

The tone by Rhode Island’s government was both extremely respectful and stern. In November, Stephen Hopkins published The Rights of Colonies Examined, which reiterated the same economic problems highlighted in the Remonstrate and the petition to the King. The sheer devastation wrought by the enforcement of the Sugar Act on New England colonies would empower both French and Dutch merchants in specific arenas of trade, and would affect other industries:

Putting an end to the importation of foreign molasses, at the same time puts an end to all the costly distilleries in these colonies, and to the rum trade to the coast of Africa, and throws it into the hands of the French. With the loss of the foreign molasses trade, the cod fishery of the English, in America, must also be lost, and thrown also into the hands of the French. That this is the real state of the whole business, is not fancy; this, nor any part of it, is not exaggeration, but a sober and melancholy truth.[13]

Hopkins continued to explain how the Sugar Act would affect Rhode Island specifically:

Heretofore, there hath been imported into the colony of Rhode Island only, about one million one hundred and fifty thousand gallons, annually; the duty on this quantity, is £14,375, sterling, to be paid yearly, by this little colony; a larger sum than was ever in it at any one time …. The charging foreign molasses with this high duty, will not affect all the colonies equally, nor any other near so much as this of Rhode Island, whose trade depended much more on foreign molasses, and on distilleries, than that of any others.[14]

If the Sugar Act was to be enforced with vigor, not only would trade in the colony stop, but the smallest colony in his North America would go bankrupt.

In the summer of 1765, the HMS Maidstone took over customs enforcement for the St. John in Newport. Under the command of Capt. Charles Antrobus, the Maidstone harassed and impressed sailors aboard trading vessels and fishing boats in Narragansett Bay. This had a serious effect on the local economy. Sailors’ wages were raised to a dollar and a half per month as an incentive to take the risk of being impressed. The lack of willing sailors brought trade with other colonies to a halt. Lumber supplies for the upcoming winter were almost nonexistent and local fishermen would rarely go out for fear of impressment. In order to man the customs vessels, the Royal Navy turned to impressment in Newport on June 4, 1765, which ushered a new wave of violence against British authorities. While a longboat of the Maidstone was docked on a wharf, a mob of five hundred confiscated the vessel and marched it to the center of the town, setting it ablaze in defiance. It only took minutes from the time the boat was stolen to the time it was destroyed.[15]

On June 1, 1765 Rhode Island’s Governor, Samuel Ward, demanded the release of the impressed inhabitants: “I must repeat my demand that all the inhabitants of this colony who have been forcibly taken and detained on board His Majesty’s ship, under your command, be forthwith dismissed.”[16] Capt. Antrobus completely disregarded this demand. On July 12, Samuel Ward sent another letter, this time directly questioning Captain Antrtobus’ authority,

But as the ship under your command lay moored in the harbor of an English colony, always ready to afford you all assistance necessary for His Majesty’s service, I could not conceive any possible reason sufficient to justify the severe and rigorous impress carried on by your people in this port. You assert that while your ship is afloat, the civil authority of this colony does not extend to, and cannot operate within her. But I must be of opinion, sir, that while she lies in the body of a county, as she then did, and still does, within the body of the county of Newport, all her officers and men are within the jurisdiction of this colony, and ought to conform themselves to the laws there of.[17]

The Ward administration never brought charges upon any citizens of Newport. The Maidstone case demonstrated that Rhode Island citizens, when their way of life was threatened, would take direct action. Royal officials wrote to their superiors to set up an official inquiry, but by the time any investigation could be initiated against the Rhode Island government, another event had taken place that caused the matter to be dropped.

The King must have been moved by the tumultuous response from his British subjects living over 3,000 miles away in Rhode Island and in other parts of America. On May 15, 1766 news came from Joseph Sherwood, the agent for Rhode Island in London, of the repeal of the Sugar Act. Sherwood stated,

You will see that every grievance of which you complained, is now absolutely and totally removed—a joyful and happy event for the late disconsolate inhabitants of America … Resolved, that the duties imposed by an act or acts of Parliament, upon molasses and syrups, of the growth, produce or manufacture of any foreign American colony or plantation, imported into any British colony or plantation in America, do cease and determine. Resolved, that a duty of one penny, sterling money, per-gallon, be laid upon all molasses and syrups which shall be imported into such British colony or plantation.[18]

Instead of just taxing foreign molasses, a duty would have to be paid on all molasses, including the molasses imported from British colonies in the Caribbean. Even this was too little too late. The resentment held by Rhode Islanders could not be lessened with the stroke from a less restrictive pen.

In 1769, a much more severe incident took place. Capt. William Reid of the sloop HMS Liberty, was tasked with patrolling the southern coast of New England for suspected smugglers. In July, the Liberty took custody of two vessels from Connecticut and brought them into Newport Harbor. The captain from one of the captured vessels had an altercation with Captain Reed over the return of some personal possessions. After he retook his possessions forcefully, the men of the Liberty open fired with a volley of muskets as the captain, with his retrieved possessions, escaped to shore. The citizens of Newport witnessed the events unfolding and became enraged by the actions of the Royal Navy. Later that evening Captain Reid and most of his crew went ashore to convene with Rhode Island governor William Wanton to answer for their conduct. Meanwhile, a group of citizens stormed the Liberty and dumped the vessel’s armaments into the harbor while cutting the mooring lines and riggings, thus rendering the ship inoperable. As the Liberty drifted towards Goat Island, it was set ablaze and destroyed. Captain Reid appealed to local authorities to apprehend and punish the individuals responsible for destroying the Liberty. In typical Rhode Island government fashion, they did practically nothing to find the culprits. Governor Wanton, although a loyalist, issued a proclamation and offered a reward to find those responsible, but no one came forward with any information.[19]

The maritime clashes between the Royal Navy and citizens of the colony only got worse. When no one was apprehended following the Liberty incident, the Royal Navy was tasked with more stringent enforcement of the Navigation Acts, which only emboldened the colonists’ in defying the British in Narragansett Bay. A revenge cycle took place and no peace could be established. The lack of respect demonstrated by the Royal Navy’s interaction with citizens only encouraged defiance towards Royal Officers. Once England threated the prosperity of commerce with enforced duties and taxes, Rhode Islanders were quick to show defiance. In a broader context, events in Narragansett Bay ingrained the spirit of the Revolution within Rhode Island’s maritime communities.

These three altercations clearly defined Rhode Island’s resentment towards the crown and were a precursor to the burning of the Gaspee in 1772.

[1] Molasses Act of 1733, December 25, 1733.

[2] David S. Lovejoy, Rhode Island Politics and the American Revolution, 1760-1776 (Providence: Brown University Press, 1958), 19. Thomas Williams Bicknell, The History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations (New York: American Historical Society, 1920), 504-505. William McLoughlin, Rhode Island: A History (States and the Nation) (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1986), 62-65.

[3] The Lords Commissioners of Trade and Plantations to the Governor and Company of Rhode Island, in John Russell Bartlett, Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, in New England, Vol. 6 (Providence: A. C. Greene and Brothers, state printers, 1856), 375.

[4] Admiral Colville to the Governor of Rhode Island, in Bartlett, Records of the Colony of Rhode Island, 6:376.

[5] Remonstrance of the Colony of Rhode Island to the Lord Commissioners of Trade and Plantations, in ibid., 6:381.

[6] Remarks on board His Majesty’s schooner, the St. John, in Newport harbor Rhode Island, in ibid., 6:428.

[7] For more on impressment in the age of the American Revolution see, Jesse Lemisch, “Jack Tar in the Streets: Merchant Seamen in the Politics of Revolutionary America,” The William and Mary Quarterly 25, no. 3 (July 1968): 371.

[8] Remarks on board His Majesty’s schooner, the St. John.

[9] Ibid., 429.

[10] Copy of an extract of a letter from Captain Smith to Lord Colville, dated Squirrel, Rhode Island, 12th July, 1764, in Bartlett, Records of the Colony of Rhode Island, 6:430.

[11] Great Britian, Parliament, The Sugar Act 1764, IV, V.

[12] Petition of the Governor and Company of Rhode Island to the King, in Bartlett, Records of the Colony of Rhode Island, 6:415.

[13] “The Rights of Colonics Examined,” in ibid., 6:421.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Newport Mercury, June 10, 1765.

[16] The Governor of Rhode Island to Capt. Charles Antrobus, in Bartlett, Records of the Colony of Rhode Island, 6:444.

[17] The Governor of Rhode Island to Capt. Charles Antrobus, in ibid., 6:446.

[18] Joseph Sherwood, Agent for the Colony in London to the Governor of Rhode Island, in ibid., 6:491.

[19] By the Honorable Governor, Captain General, and Commander in Chief of and over the English colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, in New England, in America A Proclamation, in ibid., 6:595-596. Connecticut Journal, July 28, 1769, 4.

2 Comments

The licentious Republic is an excellent article that sheds light on maritime issues that fueled the fire for the Revolution. As a 13th generation Rhode Islander with deep maritime roots the article struck a cord, clear as the bosun’s pipe.

Mr Derderian, would you please email me?

The best way to get in touch with an author is to send a message to the “editors” address – see the “About – Contact” link at the very top of the JAR home page. We’ll pass your message on to the author.