On the Topographic-Bathymetric Series Map, Eastern United States, 1:250,000, Wilmington: NJ 18-2 (1972) prepared by the United States Geological Survey located at grid WU5.5, 8.0 is a symbol for a landmark labeled, “Pulaski Monument.” This monument indicates the site of the “massacre” of the Pulaski Legion in the pre-dawn hours of October 15, 1778.[1] In Howard Peckham’s The Toll of Independence, he noted:

October 15 1778, Mincock Island, New Jersey, Casimir Pulaski’s Legion was attacked by a force of 200 British under Captain Patrick Ferguson, Pulaski reported total casualties at 25 to 30, the British thought they killed 50, British lost estimated five killed, 20 wounded, five missing.[2]

These are the basic facts of an incident in the War of Independence that is known by either the Pulaski Massacre or The Affair at Egg Harbor. It came about due to actions taken by Sir Henry Clinton, commander of British forces in New York, when at the end of September 1778, he sent a force to, “ … destroy a nest of privateers at Egg Harbor, which had done us a great deal of mischief.”[3] Little Egg Harbor (as a opposed to Great Egg Harbor located twenty miles further south) is approximately eighty miles south of New York City.[4] It served as a base for American privateers (as many as thirty armed vessels used the port) who preyed on merchantmen and transports that sailed between New York and the Southern Colonies. After entering the Old Inlet, the privateers would sail about fifteen miles to Chestnut Neck where the Mullica River empties into the bay and there they would transfer their captured cargoes to smaller vessels, then proceed up the Mullica River to the “Forks” (where the Mullica and Batsto Rivers meet), and load the captured cargoes onto wagons for a thirty-five mile trip to Philadelphia where the goods were sold for prize money.[5]

To put an end to what the British considered acts of piracy (they never recognized the American Letters of Marque as valid) along the Jersey Coast, General Clinton sent a small squadron of ships that included the Zebra (flagship), Nautilus, and Vigilant, two galleys and four smaller armed vessels, under the command of Capt. Henry Colins (sometimes spelled Collins).[6] The ground forces under the command of Capt. Patrick Ferguson consisted of about 200 men of the 5th Regiment Foot and another 100 men of the Loyalist 3rd Battalion of the New Jersey Volunteers.[7]

The flotilla left New York Harbor on September 30, 1778 but due to severe weather and contrary winds they were not able to get to the Little Egg Harbor entrance until October 5. It took another day to enter the bay and attack the American base at Chestnut Neck (today it is known as Port Republic). Once ashore, Ferguson and his men were able to drive off the few American defenders and proceeded to destroy the fortifications, houses and supplies. The privateers had advance warning of the approach of the British and were able to get away. However, a number of prize ships could not be moved and the Americans burned and scuttled them. From the Loyalist New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury we get a summary of this phase of the operation from the British point of view:

About 3 Weeks ago a small Detachment of his Majesty’s ships, 2 Gallies, and 4 armed Vessels, under the command of Capt. Collins of the Zebra, having on Board 300 Men commanded by Captain Patrick Ferguson, sailed from hence for Egg-Harbour, where after surmounting some Difficulties in passing into the Harbour, they destroyed 11 Sail of Vessels, among which a very fine Ship, the “Venus of London,” and others of considerable Size. The Troops being landed, proceeded to destroy the Settlements and Store Houses of the Committee-Men and every Person notoriously concerned in the Pyratical Vessels, which have greatly annoyed the British commerce from that Quarter. The Salt works on the Bay were also effectually destroyed.[8]

The second part of the British plan, to continue up to the “Forks,” was abandoned due to the risk of sailing up the shallow and shoaled channels of the Mullica. Loyalists informed them about the growing number of “rebel” troops both regular (Pulaski’s Legion and Proctor’s Artillery) and New Jersey militia converging on the Jersey Shore. Brig. Gen. Casimir Pulaski and his Legion, which had recently been inducted into the Continental Army, arrived at Trenton on October 5, 1778. The New Jersey Gazette of October 7 described the orders of the newly created Legion:

General Count PULASKI, with his Legion of Horse and Foot, arrived here on Sunday last from Pennsylvania. Monday evening the General received intelligence that the enemy were about to make a descent upon Egg Harbour, and yesterday morning he marched for that place with all his troops, in high spirits and with alacrity.[9]

Francis B. Lee’s, New Jersey as a Colony and as a State described the Legion’s march to the Jersey Shore:

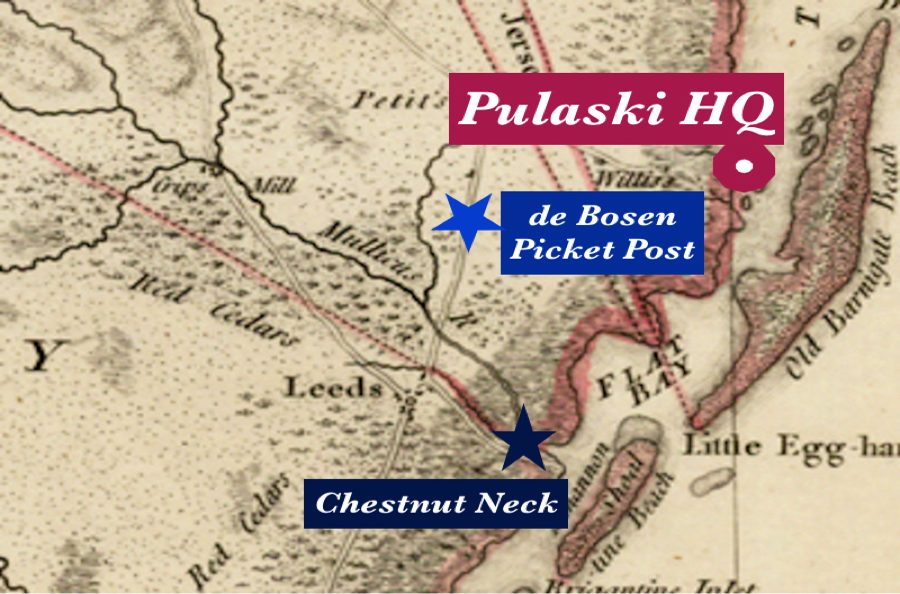

From the 6th to the 8th of October they had sped through the farms and pines of Burlington County, from Trenton to Tuckerton, the famous legion of Pulaski, which upon its arrival camped upon the old Willets farm, south of the latter village. There were three companies of light infantry, a detachment of light artillery, and three troops of light horse. . . . From Count Pulaski’s headquarters a lane led to the bay, and behind a clump of trees, protected from observation, was the camp of the legion. Nearer the meadows was a picket commanded by Lt. Col. Baron de Bosen, while beyond lay Big Creek and Osborn’s island.[10]

The British plans to leave the area were put on hold (Colins received orders on October 10 to return to New York) due to the shift in the winds, which did not allow the ships to leave Egg Harbor; a number of vessels ran aground on sand bars.[11] While awaiting a change in the weather, a new opportunity to inflict damage on the Americans presented itself to the British in the form of a deserter from the Pulaski Legion, one Lt. Gustav Juliat.

Disposition of the Pulaski Legion at Little Egg Harbor[12]

Gustav Juliat had been an officer in the Hessian Landgraf Regiment who, while stationed in Rhode Island in 1777, deserted to the Americans. He requested a commission with the Continental Army and eventually was given a post as a sub-lieutenant with the Pulaski Legion.[13] However, Lt. Col. Charles August Baron von Bose (sometimes spelled Bosen), the commandant of the infantry of the Pulaski Legion, showed great distain for Juliat due to the fact that he had deserted his colors. Because of von Bose’s negative attitude towards him, Juliat developed a great hatred for him and decided to seek his revenge.[14] On October 13, Gustav Juliat, along with five others, said they were going fishing but instead rowed out to the British ships and gave to Colins and Ferguson details of the deployment of Pulaski’s Legion, pointing out their weak points.[15] Further, he stated that Pulaski had ordered his legionnaires not to give quarter to the British, which was to have deadly consequences for the Americans.[16]

The next day (October 14), just before midnight, Ferguson, Juliat and about 150 troops rowed across the bay to a place known as Osborn Island, which was the farmstead of a Quaker family, headed by Richard Osborn. His son Thomas was forced to act as a guide to lead the British to the American lines. They came upon a bridge over Big Creek (amazingly the Americans had not posted any sentries!) then proceeded about a mile up Island Road. They captured a sentry who was not able to give an alarm, and at about 4 AM (October 15) surrounded and then attacked the farmhouse (known as the Ridgeway Farm) in which part of the infantry (about fifty Legionnaires) were sleeping. At the outset of the attack, von Bose tried to rally his men to break out of the trap. He led them out of the farmhouse to counter attack but was immediately cut down, along with Lt. Joseph de la Borderie and about forty men. A few Legionnaires were able to escape into the pines and five were taken prisoner.[17]

The main body of the Pulaski Legion was located about a mile away at Willets Farm. The sound of gunfire roused them into action. By the time Pulaski and the cavalry arrived at the picket post, however, the British had left and they only found the dead and wounded Legionnaires. Pursuing the attackers, Pulaski’s troopers came to Big Creek, but the British had destroyed the bridge and the horses could not ford the stream. A few of the infantry swam across but because the cavalry or artillery could not support them, the pursuit was ended.

Pulaski returned to the site of the “massacre,” took care of the wounded and buried the dead. At this point Thomas Osborn, who had been hiding in the woods, came out and told of his being forced to guide the British troops. A number of the Legionnaires did not believe his story; they tied him to a tree with the intention of flogging and then executing him for what they perceived as his treachery. He was spared this fate only when an officer stopped the men from continuing with their planned revenge and took Osborn into custody. Later his father was also arrested and both were sent to Trenton to be tried for aiding the enemy.[18]

When morning broke, Ferguson and his men were still on Osborn Island, planning their next move, when a Loyalist farmer informed him that Proctor’s Artillery and a large force of militia were on their way. Ferguson decided it was time to head back to the ships and in the early afternoon (October 15) they rowed back across the bay. Once the troops were on board, Captain Colins set sail for the open sea, but again a shift in the wind caused the flag ship Zebra to run aground on a sand bar and the men were transferred to the Nautilus and Vigilant. Still unable to free the ship, it was decide to fire it; it was reported that the Americans were amused “when the shotted guns were discharged as the flames reached them.”[19]

While originally ordered to return to their homeport on October 10, it wasn’t until the 19th that Captain Colins was able to leave the area. He arrived back in New York on October 23. For the British, the operation was considered a success in that they destroyed the privateer base at Chestnut Neck. They did miss out on accomplishing their other objectives of capturing the privateers and their vessels (the ones destroyed at Chestnut Neck were scuttled English prize vessels). Nor were they able to destroy the base at the Forks, along with the iron works at Batsto. They did get a tactical victory over the Pulaski Legion, killing over forty Legionnaires, including the commandant of the infantry, Lt. Col. von Bose, with only two members of the 5th Regiment and one from the 3rd New Jersey Volunteers killed and six to ten missing or wounded.[20]

Pulaski sent two letters to Henry Laurens, President of the Continental Congress, in which he described the attack on his outpost and the reasons for the British success. In the first, he laid the blame on Juliat; he noted: “The enemy, excited, without a doubt by this Juliet, attacked us the fifteenth instant at three o’clock in the morning, with four hundred men. . . .”[21] In the remainder of the letter he described the actions that he and Legion took to repel the attackers. In the second letter he lamented that only the Legion fought the British and the militia were next to useless: “None but the Legion were engaged, Major montfort had been sent to the forks to gather and bring the Militia but half of them were gone home and the remainder form’d so many difficulties that they almost mutinied against Major Montfort. . . .” Also in the report he noted that the Egg Harbor area contained many Loyalists: “I shall be at last forced to search the houses and take the Oath of Fidelity from the Inhabitants otherwise I shall be continually exposed . . . but be assured I will neglect no means to contain them and at the same time stop the Ennemy.”[22]

The Americans and Pulaski did view the engagement as a “victory” in that they were able to drive off the British before they were able to inflict greater damage. Pulaski remained in the area until he was certain that the British were gone; thinking at first that the British might attack further north along the coast, he moved the Legion to Stafford and Barnegat. Finally, when there was no longer a threat, the Pulaski Legion headed back to Trenton, arriving around the 22nd or 23rd of October.

As a postscript to the Affair at Egg Harbor, it is interesting to note what happened to the Osborns and Juliat. As previously stated, Thomas and his father, Richard Osborn Jr., who were Quakers, were taken to Trenton to stand trial. They were found to be blameless and were given the following pass that allowed them to return home:

Permit the bearers, Richard and Thomas Osborn, to pass to their home at Egg Harbor; they being examined before the Judges at Trenton, and not found guilty, are therefore discharged and at liberty. By Order of General Pulaski, Le Bruce de Balquoer, Aid De Camp, William Clayton, Justice of the Peace. Hugh Rossel, Jailer. Trenton, October 30, 1778.[23]

When Juliat arrived in New York and his true identity was discovered, General Clinton at first had him put under arrest but he was soon released. The harshest criticism for Gustav Juliat, the double deserter, came from a fellow German, Capt. Johann Ewald, who wrote in his memoir:

This miserable human being, who had betrayed his friends and served major Ferguson as a jackal, was a Mr. von Juliat, who had run away from the Landgraf Regiment at Rhode Island. He took employment with the enemy and was placed with the newly raised Pulaski corps. After his trick at Egg harbor, he admitted his perjury to the English major, who obtained a pardon for him from General Knyphausen by petition of General Clinton. But since he found that everyone in New York despised him, he took employment on an English privateer.[24]

Upon his return to Trenton after the “Affair at Egg Harbor,” Pulaski requested that the Legion be sent to Kings Bridge in New York to serve as a “flying corps” that could both reconnoiter and harass the British in the area. He noted that a partisan corps was most effective when it acted independently of the main army.[25] On the same day, however, he received the following order: “Resolved: that Count Pulaski’s Legion and all the cavalry at or near Trenton, be ordered, forthwith, to repair to Sussex Court house, there to wait the orders of General Washington.”[26] The Pulaski Legion was being sent to Sussex Court House (Newton, New Jersey) so they could provide protection for the inhabitants of the Upper Delaware River Valley, an area known as the Minisinks.[27]

The reason for the Pulaski Legion’s posting to the Minisinks was a number of bloody incursions by the Tories and their Iroquois allies during 1778. On July 3, Col. John Butler led an attack on the Wyoming Valley (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania) on the Susquehanna River about fifty miles west of the Delaware. Then later in the month, Col. Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea) with a party of Mohawk, Seneca, and Loyalist rangers, attacked and burned Cole’s Fort at Mackhachameck and the surrounding area (today Port Jervis, New York and Montague, New Jersey).[28] Soon after arriving in northwestern New Jersey, it became apparent that Pulaski was not pleased with his assignment; rather, he felt it was an insult to his honor or as he stated in a letter to Congress: “I demand to be employed near the enemy’s lines, and it is thought proper to place me in an exile which even the savages shun, and nothing remains but the bears to fight with.”[29]

On November 15, 1778 Pulaski sent Washington a letter explaining his Legion’s situation in the Minisinks and hinted at returning to Europe: “. . . I hope that after returning the Legion to its place and bringing it into good order I shall have your permission to go to Philadelphia. It is necessary in order to arrange the embarkation. My ambition cannot be satisfied by the command of the Corps at quarters or battling the enemy not worth fighting, a victory over whom brings no honor . . .[30]

Why did Pulaski plan to resign his commission and return to Europe? It had to do with both his personal situation and the future of the war. On the personal level, Pulaski was depressed with his situation in America. He believed he was being unjustly criticized for poor accounting of the expenses of the Legion and there were the constant reminders to keep his men under control. Regarding the war, with the British ensconced in New York City and the Americans controlling the hinterland, both sides came to believe that the war was at a stalemate, with little chance of either side striking a crippling blow or even meeting in a major engagement. During Pulaski’s stay in Philadelphia, however, he changed his mind about resigning and returning to Europe. He seems to have acquired a renewed fervor for the Patriot cause.[31]

What caused this change in plans? Mainly it had to do with the possibility of seeing action in a new theater of war. The British government, with the concurrence of the commanding general of British forces in North America, Sir Henry Clinton, came up with a new strategy to move the war to the southern colonies, where they believed they had more Loyalist support. In turn, the Americans decided to meet the British challenge and increase the American military presence in the South. At the outset, the only mobile force that they could send quickly was Pulaski’s Legion.

While in Philadelphia that winter, Pulaski met with members of the Board of War to hammer out details of his new assignment. Finally on February 2, 1779 the Continental Congress passed the following resolution: “Resolved, That Count Pulaski be ordered to march with his Legion to South Carolina, and put himself under the command of Major General Lincoln or the commanding officer of the Southern department.”[32]

The Legion’s infantry set off first on March 18, 1779 followed by the cavalry on the 28th. It took the Legion sixty days to reach Charleston, South Carolina, averaging fifteen miles a day. Pulaski, at the head of the cavalry, arrived at Charleston on May 8, 1779, with the infantry arriving on the 11th; they immediately saw action against the British in their attempt to capture this important southern port city. Having distinguished themselves in this endeavor but enduring devastating losses, Pulaski and the Legion continued to provide service throughout the summer of 1779 in the southern theater under the command of Gen. Benjamin Lincoln.[33]

Casimir Pulaski’s end came when American forces, along with the French, tried to drive the British out of Savannah, Georgia. Here on October 9, 1779, while leading a charge against British positions, Pulaski was mortally wounded. He died of his wounds on October 11, 1779, bringing to a conclusion what was a brief, controversial, but undoubtedly heroic career for this enigmatic figure in American History. Upon hearing of Pulaski’s death, King Stanislaw Augustus Piontowski, against whom Casimir Pulaski led the Confederation of Bar rebellion, supposedly stated: “Pulaski has died as he lived – a hero – but an enemy of kings.”[34] After Pulaski’s death, the Legion continued meeting with ill luck. On April 14, 1780, Banastre Tarleton at Monck’s Corners decimated the remnants of the Legion, along with units of the Continental cavalry. Finally, in September 1780, the Pulaski Legion was disbanded and the surviving legionnaires taken into Armand’s Legion.[35]

[1] Pulaski Legion Memorial (erected in 1894) inscription: ”This Tablet is Erected by the Society of Cincinnati in the State of New Jersey to Commemorate the Massacre of a Portion of the Legion Commanded by Brigadier General the Count Casimir Pulaski of the Continental Army in the Affair at Egg Harbor, New Jersey October 15, 1778 in the Revolutionary War.” Photograph taken by author.

[2] Howard Peckham, Toll of Independence: Engagements & Battle Casualties of the American Revolution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974), 55. The reports of the casualties and damage inflicted by both sides varied greatly. An example is from Capt. Johann Ewald, an Hessian officer, who reported that, “. . . over sixty Americans were killed including seven officers, 250 prisoners taken, four cannon captured and a cash box of paper money. Johann von Ewald, Diary of the American War: A Hessian Journal (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 152-153.

[3] Henry Clinton, The American Rebellion: Sir Henry Clinton’s Narrative of his Campaigns, 1775-1782, With Appendix of Original Documents (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954), 105.

[4] Little Egg Harbor referred to the inlet leading to the Mullica River; the bay was then known as Flat Bay and today it is Great Bay. The Mullica River was also known as Little Egg Harbor River.

[5] William Stryker, The Affair at Egg Harbor, October 15, 1778, speech given at the dedication of the Pulaski Massacre Monument, July 3, 1894 (Trenton: Naar, Day and Naar, 1894), 9, online at babel.hathitrust.org.

[6] For a complete list of British ships and forces see Franklin W. Kemp, A Nest of Rebel Pirates (Egg Harbor City: Laureate Press, 1966), 14-15.

[7] Two years later (October 7, 1780) Ferguson, then a lieutenant colonel, was killed in a surprise attack by Patriot militia at King’s Mountain, North Carolina.

[8] Francis B. Lee, ed. Extracts from American Newspapers, Archives of the State of New Jersey, 2nd Series, vol. II (Trenton: John L. Murphy, 1903), 499-500 (hereafter Extracts). Ferguson led a raid across the bay, on the Bass River, destroying Whig salt works and property, in particular those of Eli Mathis, identified as a leading “Rebel” in the area. For a description of this foray see Stryker, The Affair at Egg Harbor, 9-10.

[9] New Jersey Gazette, October 7, 1778, Extracts, 464.

[10] Francis B. Lee, New Jersey as a Colony and as a State: One of the Thirteen (New York: Publishing Society of New Jersey, 1902), 2:322-323.

[11] Little Egg Inlet continues to be a problem for boaters. In the Spring of 2017, the Coast Guard removed navigation buoys from the inlet due to shoaling and the inlet is scheduled for a major dredging operation.

[12] Dispositions of Pulaski Legion placed on William Faden’s Map: Province of New Jersey, Charing Cross, December 1777.

[13] Worthington C. Ford, ed., Journals of the Continental Congress (Washington: Govt. Printing Office, 1908), 867-8 (hereafter JCC), archives.org. In JCC he is referred to as “Charles Juliat” and in a number of narratives his last name is spelled “Juliet.”

[14] Who was Lt. Col. Charles August Baron von Bose (also referred to as de Bosen)? In Franklin W. Kemp, A Nest of Rebel Pirates, there is an interesting chapter titled “The Mysterious Baron Bose,” 54-69, in which the author describes the thorough and painstaking research he did in trying to identify this foreign officer in the service of the Continental Army. In Kemp’s research he mentions that one of von Bose’s relatives was the commander of the Landgraf Regiment from which Juliat deserted; could this have added to his distain of Juliat? Francis Kajencki, The Pulaski Legion in the American Revolution (El Paso: Southwest Polonia Press, 2004), 64, mostly using Kemp’s research, identifies him as a “scion of a prominent Saxon family in Europe.”

[15] With regards to the disposition of the Legion at the Jersey Shore, Captain Ewald noted that Pulaski was lucky in that, “. . . it had occurred to him [Pulaski] the previous day to look for another post, as this one did not seem safe enough, and consequently he was not present.” Ewald, Diary of the American War, 152-153.

[16] Juliat at first identified himself to Ferguson as a Frenchman named Bromville. Stryker, Affair At Egg Harbor, Appendix: “Report of Capt. Ferguson to Sir Henry Clinton, October 15, 1778, Little Egg Harbor,” 31. In the Third Infantry Company of the Pulaski Legion was a Frenchman, Lt. James Bronville; most likely Juliat took his identity. See Kajencki, Pulaski Legion for a list of Pulaski Legionnaires, Appendix F, Muster Rolls, 317-339.

[17] Stryker, The Affair at Egg Harbor, 19.

[18] Leah Blackman, History of Little Egg Harbor Township, Burlington County, N.J.: from its first settlement to the present time (Salem, MA: Higginson Book Co., 1994), 281.

[19] Lee, New Jersey as a Colony and as a State, 322.

[20] Stryker, The Affair at Egg Harbor, 31. He includes in Appendix, 23-32, the reports submitted from both Captain Colins and Captain Ferguson to Gen. Henry Clinton on their actions at Egg Harbor.

[21] Papers of the Continental Congress, microfilm 247, roll 181, index 164, 17 (hereafter PCC).

[22] PCC, 38.

[23] Blackman, History of Little Egg Harbor Township, 281.

[24] Ewald, Diary, 153. Maj.or Carl Baurmeister noted that Juliat joined Captain von Diemar’s Hussar Freikorps which was part of the Loyalist Queen’s Rangers and didn’t leave America until January 1781. Carl Baurmeister, Revolution in America, Confidential Letters and Journals 1776-1784 of Adjutant Major General Baurmeister of the Hessian Forces, Bertram A. Uhledorf, ed. (New Brunswick: Rutgers Press, 1957), 390.

[25] PCC, 46. Kings Bridge is at the northern end of Manhattan where it meets the Bronx.

[26] JCC, v. XII, October 26, 1778, 1061.

[27] It covers more than forty miles from the Delaware Water Gap to Port Jervis, New York (at that time known as Cole’s Fort or Mackachameck), then as the Delaware turns in a northwesterly direction, for another forty or so miles to Cushetunk (Narrowsburg, New York).

[28] In November, Capt. Walter Butler (John’s son) destroyed the Cherry Valley settlements about fifty miles west of Albany. In 1779, Colonel Brant again attacked the Minisink area, further to the northwest at Narrowsburg, New York. To settle this problem of Loyalist and Indian raids, Washington sent Maj. Gen. John Sullivan with a large force to pacify the region.

[29] PCC, 68.

[30] The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 18, 1 November 1778 – 14 January 1779, Edward G. Lengel, ed. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2008), 157–158, http://founders.archives.gov.

[31] Pulaski arrived in Philadelphia in the beginning of December 1778 and remained there through January 1779 until the Legion’s cavalry was reassigned to Wilmington, Delaware.

[32] JCC, v. XIII, February 2, 1779, 132.

[33] Colonel Kovatch, commandant of the cavalry, was killed at Charleston and Pulaski’s cousin Capt. Jan Zelinski, who accompanied him from Europe, was mortally wounded (he died in September) and the British reported that Pulaski’s losses (killed, wounded and captured) were between forty and fifty men. Kanjecki, The Pulaski Legion, 137.

[34] Leszek Szymanski, Casimir Pulaski: A Hero of the American Revolution (New York: Hippocrene Books, 1994), 290n.

[35] Even in death Pulaski remains something of an enigma. He died aboard the Wasp and it was thought he was buried at sea. In 1996 when the Pulaski Monument in Savannah was undergoing renovations workmen found a box with “Cassimer Pulaski” written on it. Following a somewhat inconclusive forensic investigation, it was decided to treat the remains as those of Brig. Gen. Casimir Pulaski and in October 2005 they were re-entombed with full military honors, involving both American and Polish Armed Forces. For a full description of the discovery, investigation and military honors see Edward Pinkowski, Pinkowski Files, at www.poles.org.

Recent Articles

The Battle of Burke County Jail, Georgia

When Some Americans First Lost Their Constitution

The Great Contradiction: The Tragic Side of the American Founding

Recent Comments

"The Complicated History of..."

Carole, Thank you, I appreciate that. I agree that much of what...

"The Sieges of Fort..."

I very much enjoyed your well-written article. Interest in the site continues,...

"An Enemy at the..."

Bob: Great Article! I never heard of Abraham Carlile and his fate....