Lt. Col. Anthony Walton White of the 3rd New Jersey Regiment had a very rocky 1776. His service was peppered with several episodes more indicative of a trouble-making non-commissioned officer than the second highest ranked officer in the regiment. He was a primary instigator of a duel between two junior officers. Granted the duel was rigged with paper wad bullets, but it was something a man in his position should not have taken part in.[1] Furthermore, he was definitely involved with the regiment’s officer corps’ plundering of Johnson Hall. One of the initial suspects, he was acquitted of all charges in a legal whitewash of the matter. Evidence indicates he may have been the one who provided the plunderers access to the Hall.[2] It also does not take much to suspect that, as the ranking officer in the area, he may have been the catalyst for the entire operation.

By any account, this is a serious supposition. However, it may be a correct one. Regimental commander Col. Elias Dayton knew there was something going on with White. Just after the regiment arrived at Fort Ticonderoga in early November 1776, a homeward bound Dayton wrote Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler that, “If Col. White could return with me, I think it would be for the good of the Regiment.”[3]

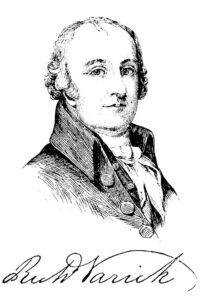

No action was taken on this request. In fact, Dayton was still at Fort Ticonderoga when on November 18, 1776, a visiting Richard Varick, the Deputy Muster Master General of the Northern Department,[4] was accosted by Colonel White.

Varick reviewed the bizarre incident, and his feelings about it, in two letters sent from Fort Ticonderoga to Major General Philip Schuyler.[5] In the first letter, dated November 18, Varick explained:

You will be astonished at the horrid intention of assassination which was attempted against me this noon & on my arrival at this post.

Col. White being informed of my arrival here, came down to headquarters. General Gates took me out of the house to speak to me on the subject of my duty, and in our walk, met Col. White but took no notice of him. On our return to the door, Col. White called me aside. As I supposed that he intended to speak to me, for my taking liberty with his character, I freely stepped to the back of the general’s house, and no sooner had we got about 5 paces beyond the kitchen than his small sword was drawn & pointed and I retreated two paces. I damned him & asked what he meant by it, he bid me draw and defend himself. I retreated & damning him asked what he meant by it, he pursued me so closely that I ran before the general’s door, where by the [ ] saved myself from a damnable premeditated murder.[6]

Thankful that White had not used his pistols to shoot him outright, Varick, who was now in fear for his life, applied to Major General Gates for protection. In order to prevent Varick from being attacked again, Gates had White arrested. Brig. Gen. Benedict Arnold ordered White secured in his own quarters with “two Continentals at his door.”[7]

However, before getting there, White somehow escaped arrest. Accordingly, Gates ordered Maj. Francis Barber of the 3rd New Jersey to send out search parties to take him dead or alive. One of them found White in the woods, heavily armed, and sitting on a stump. The unnamed officer in charge of the party advanced to him, but White “cocked and pointed his pistol swearing by God he would shoot him in case he did not stand off.” The officer advanced again but this time he pointed his own pair of pistols at White, explaining he had orders to take him dead or alive. White still resisted, asking by whose orders the party was sent. When told it was General Gates, White surrendered.[8]

White was again placed in his quarters as previously intended. He had been armed with four pairs of pistols, two small swords, and a cuttoe. One of the small swords and a pair of the pistols belonged to Pennsylvania’s Col. Anthony Wayne. White explained that he was waiting in the woods for Varick, presumably to have a duel, and he expected that Wayne would have told Varick of it.[9]

Varick detailed in his letter that he learned the evening of November 18 that Gates had:

… given Wayne leave to withdraw the Continentals from White’s door which is done on Wayne’s giving his word & honor for my security & White’s complying with his close arrest. —I wanted of Col Wayne to know by whose orders & what authority the Continentals were withdrawn & he informed me that he had ordered the Continentals to be withdrawn by General Gates’s leave. And I am informed that General Gates has given him power to give White a furlough to go to Brunswick free from arrest.[10]

Outside of a passing mention of the initial assault, there appears to be nothing in contemporary documents confirming the incident. Luckily, 2nd Lt. Ebenezer Elmer made a brief entry in his personal journal describing it (skipping over the attempted duel/ambush in the woods):

This morning Colonel White, having an enmity against Colonel Varick, Muster M. General (for some ill usage which he had received from him) called him out at one side and instantly drew his sword, telling him to draw likewise, or he would run him through. Colonel Varick, not drawing an equivalent weapon, stepped back and was obliged to make the best of his way off to prevent being assassinated on the spot. Colonel White was immediately put under arrest, but went off from the Brigade-Major, upon which an officer and file of men were sent after him and he, after being taken, was confined to his room under guard ’til he be sent away for trial.[11]

Varick also used his first letter to Schuyler to offer a few biting five-dollar words to describe White’s character:

As I have the fullest evidence to prove White a “rascal, & scoundrel, & villain & a man of the blackest heart which God Almighty ever created”— being those expressions I avow to have made use of against him—I am determined to hunt him out of the army, as I cannot with safety to myself suffer a man who has attempted to murder me, to remain on a footing with myself. —I must therefore entreat you my dear general to have him arrested, if he is discharged by Col. Wayne, that he may carry infamy with him, even if he should be permitted to go to New Jersey, and that he may be tried as soon as my duty is executed so as to be able to attend to it.[12]

Varick went on to tell Schuyler that he was desirous of to pursuing a formal court-martial of White, with himself as his own attorney, but would defer to General Schuyler’s decision. Varick also explained that captains Ross and Patterson of the 3rd New Jersey, who solicited for White, stated he wanted to have matters settled. White acknowledged his “imprudent conduct” towards Varick and wanted him to confess to taking liberties with his character. In the spirit of cooperation, Varick was willing, but made it clear that the power to make such a settlement was taken out of his hands by White’s actions of that day. In anticipation of another possible attack by White, Varick wrote in a postscript that “I have a pair of pistols as my guardian angels & am advised by Gates and Arnold not to go unarmed till White is removed.”[13]

In his first letter to Schuyler, Varick shows an inherent knack for political double-speak. Where he chastised White in no uncertain terms, Varick wanted Schuyler to intercede and bring him under control. Apparently, this way he could be outraged, but not do anything about it, as Schuyler would be responsible for restraining him. Varick also danced around his feelings about Wayne’s involvement:

You will here judge how far Mr. Wayne is concerned. —I wish however my dear general, that nothing may be said or done with respect to Col. Wayne till I am able to give you further information…. —I am informed & have reason to believe the matter is managed at Wayne’s intercession, who I believe has acted a part which I cannot approve & therefore have taken a birth with Major Barber as Col. Dayton is going off…. I must in justice to Col. Wayne, say that he behaves polite to me & has insisted that I take my quarters with him. I shall consider of it.[14]

After White was settled down, general orders on November 18, 1776 stated that “… Col. Dayton is to march Lt. Col. White in arrest to Albany, for attempting to assassinate Mr. Varick, D. M. M. Gen’1, near Head Quarters.”[15] Ironically, this is what Dayton had wanted to do back on November 5, sans the arrest, but, he had not yet left Fort Ticonderoga. Dayton did not have long to wait.

The Continental Army Northern Department was quickly being downsized. Winter was coming. The British forces threatening the fort had withdrawn on November 3. Enlistments were running out. The 1st and 2nd New Jersey Regiments left Ticonderoga on November 14, following the prior arrival of the 3rd New Jersey.[16] The 24th and 25th Continental regiments had left on November 18, as did Colonel Porter’s (unnumbered) Battalion.[17] These were followed by thirteen more regiments slated to leave by the first available boat or, for a couple of the New Hampshire regiments, march overland by the shortest and best route.[18]

In addition to the men, the Northern Army was also hemorrhaging members of the senior leadership. Dayton had wanted his poorly clothed regiment relieved, but at the very least he wanted to go home for unspecified reasons.[19] He got his wish on November 20 and was allowed to leave.[20] Both Major General Gates and Brigadier General Arnold had already left on November 18. Brig. Gen. William Maxwell, of New Jersey, had also left. All of these departures left only Colonel Wayne in command of Fort Ticonderoga.[21]

General orders dated November 20, stated that:

Lt. Col. White having engaged his honor not to challenge or offer violence to Capt. Varick, D. M. M. Gen’l to the Army, until they have had an opportunity of settling the unhappy dispute in an honorable manner, is released from his arrest on the occasion, by the order of the honorable Major Gen. Gates.[22]

That very day, Colonel Wayne used almost the same language writing to Brig. Gen. Horatio Gates, where he confirmed that, “Colonel White has given his honour not to challenge or offer any violence to Captain Varick, until their friends have had an opportunity of settling the affair in an honourable way.” In addition, a postscript was added to the bottom of the letter, which read in part, “Colonel White is on his way across the lake, and liberated, according to your orders.”[23]

Meanwhile, in the second letter to General Schuyler, Varick, who was still at the Fort, explained he had not let the matter go and how much he wanted to dishonor White. Yet, he was again willing to have his superior, Schuyler, prevent him from doing so:

When I consider the many instances of infamous & ungentlemanlike conduct of Lt. Col. White as well with respect to some of my friends as myself, I am but justly fired with the most keen resentment, in as much that I think it my indispensible duty to persecute the scoundrel, till he is dismissed the army, with the disgrace due to his base character. I shall thereupon take up the matter with a doubled ardour I leave no stone unturned (as far as justice & propriety will mark my conduct) to load him with disgrace, till I have the pleasure of thinking that my friends and myself have our columinaitor & intended assassin humbled at our feet. —Then I shall cheerfully quit my pursuit. —In this however my dear gen. you will restrain me, when I exceed the bounds of moderation.—

You may think me warm, but I assure you, I have severely felt & [hated?] the insults & injuries he has perpetrated.[24]

Varick continued with his frank thoughts about White being released and allowed to return to Brunswick, New Jersey, on his own parole:

I feel dissatisfied at General Gates’s changing his orders respecting Col. White. It is Wayne who influenced him so much, notwithstanding General Arnold’s opposing it. —The last gentleman was informed of some masters by Col. Dayton which convinces him that White had no honor. —Now, my dear sir, as Wayne had leave to send him to Brunswick on parole & as White has no honor, what compliments do I pay myself in permitting him to have this priviledge? —As I have reason to think that some officers do not hold themselves bound by your orders, I wish their views to be disappointed, the haughty to be humbled. —I am determined to mark some characters & treat them with as much indifference as my duty to them & myself can permit. —[25]

Despite Varick’s personal frustrations with White being allowed to leave the Army, the matter was essentially settled and further action was not required by General Schuyler. Capt. Joseph Bloomfield was almost immediately appointed major.[26] Major Barber would be promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel late in November.[27] Varick would continue as the Deputy Muster Master General, and would review six companies of the 3rd New Jersey on November 23.[28]

Lieutenant Elmer wrote a curious and unexplained comment in his journal, following his notation that White had been released on his promise:

What cannot friends do when their powers are exerted for our security—robbers and murderers have often been rescued from death by their interposition; but a day of just reckoning is coming, in which strict justice shall take place. Is there not some hidden curse in the stores of Heaven, red with uncommon wrath, to blast the man who owes his greatness to his country’s ruin.[29]

Taking the long view, there has never been an explanation for Anthony White’s bizarre behavior during the 1776 campaign. His career, after leaving the 3rd New Jersey, was apparently stellar. He served gallantly as a lieutenant colonel of the 4th and 1st Light Dragoons. He was promoted to colonel of the 1st Light Dragoons early in 1780. He was a prisoner for five months later that year. After being exchanged, White led the 1st Light Dragoons until he retired in 1782. Returning to the army after the Revolution, he was made a brigadier general in 1798. He retired from the United States Army in 1800.[30]

Living for a significant time in New York City after the Revolution, White was an original member of the New York Society of the Cincinnati. Their records show he was appointed aide-de-camp to General Washington in October 1775. He may have never served, as the appointment was just three months prior to his being commissioned lieutenant colonel of the 3rd New Jersey. They also noted, in 1794, White was in command of the cavalry that was part of the forces sent to put down the so-called Whiskey Rebellion in Western Pennsylvania. After the Revolution White attempted, with little success, to get Congress to reimburse him for personal funds he had used to provide needed equipment to his old regiment, the 1st Light Dragoons.[31]

In addition to White, the New York State Society of the Cincinnati indicates that Varick, who would go onto a long career in public service, was one of their original members, as well as Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton.[32] Considering the vitriol between these two sets of antagonists, their regular meetings had to have been something to behold.

[1] Philip D. Weaver, “The 3rd New Jersey Regiment’s Mighty Dueling Frolic,” Journal of the American Revolution, https://allthingsliberty.com/2016/09/3rd-new-jersey-regiments-mighty-dueling-frolic/

[2] Philip D. Weaver, “The 3rd New Jersey Regiment’s Plundering of Johnson Hall,” Journal of the American Revolution, https://allthingsliberty.com/2017/05/3rd-new-jersey-regiments-plundering-johnson-hall/

[3] Col. Elias Dayton to Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler, November 5, 1776, Fort Ticonderoga Museum, Thompson-Pell Research Center, M1949. Lieutenant Colonels are addressed and often referred to as “Colonel.”

[4] A muster master was essentially an inspector. They would take an account of troops and of their equipment in order to report to their superiors. Varick, a former company commander with the 1st New York, had been serving as secretary to Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler, before being promoted to his present position. In the documentation presented here, Varick is referred to either as the rank of “captain” or “colonel.” Officially, the position came with a rank of lieutenant colonel. Resolution of the Continental Congress, November 7, 1776, Worthington C. Ford, ed., Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1906), 6:933.

[5] Both letters are part of the Philip Schuyler Papers in the Manuscripts and Archives Division of The New York Public Library, but were published in Politics of Command in the American Revolution by Jonathan Gregory Rossie in 1975. It is from the latter that the selected excerpts are quoted.

[6] Richard Varick to Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler, November 18, 1776, in Jonathan Gregory Rossie, The Politics of Command in the American Revolution (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1975), 215-217.

[7] Ibid. Ebenezer Elmer, “The Lost Pages of Elmer’s Revolutionary Journal,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society, New Series, 10 (October 1925):417-418, entry for November 6, 1776, the 3rd New Jersey began moving into “the old French fort.” It would have to wait for the other New Jersey regiments to return home to complete the process. By the time of this incident, it is unclear where White’s quarters were. Since there was a door, he was probably quartered in one of the outbuildings across from the gate.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid. A cuttoe is a kind of hunting sword that was popular among those Continental Army officers who had no military sword of their own to carry.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Entry for November 18, 1776, Ebenezer Elmer, “The Lost Pages of Elmer’s Revolutionary Journal,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society, 10 (1925):423-424. A Brigade Major was the adjutant for a brigade of troops and was responsible for distributing orders to them via the regimental adjutants. The title was more a staff function, and the position could be held by an officer of any rank. When soldiers are formed up into two or three ranks, the men, one behind the other, are known as a file. So, depending on how many ranks the 3rd New Jersey formed up in, “a file of men” would be two or three men.

[12] Richard Varick to Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler, November 18, 1776, in Rossie, Politics of Command, 215-217, Richard Varick to Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler, November 18, 1776.

[13] Ibid. Captains Ross and Patterson were also key suspects in the plundering of Johnson Hall along with Colonel White. So, their serving as White’s seconds in this matter is not a surprise.

[14] Ibid.

[15] General order dated November 18, 1776, in Ebenezer Elmer, “Journal Kept During an Expedition to Canada in 1776,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society, 3 (1848):43.

[16] General order dated November 14, 1776, in ibid.,42.

[17] Ibid., 42, entry for November 17, 1776. Elmer listed them as “Col. Graton’s, the late Col. Bond’s and Col. Porter’s Regiments.” Colonel Greaton commanded the 24th Continental. The 25th had been commanded by Col. William Bond. Col. Elisha Porter’s Regiment was an unnumbered battalion. All three were Massachusetts’s regiments.

[18] General order dated November 18, 1776, in Elmer, Journal, 42-43. .

[19] Dayton to Schuyler, November 5, 1776.

[20] Elmer, Lost Pages, November 19, 1776, 424. Rossie, Politics of Command, 215-217, Richard Varick to Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler, November 18, 1776.

[21] Elmer, Lost Pages, entry for November 18, 1776, 424.

[22] General order dated November 20, 1776, in Elmer, Journal, 43.

[23] Col. Anthony Wayne to Brig. Gen. Horatio Gates, November 20, 1776, in Peter Force, ed., American Archives (Washington, D.C., 1837-53), 5th Series, 3:785.

[24] Richard Varick to Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler, November 20, 1776, in Rossie, Politics of Command, 217-218.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Entry for November 20, 1776, Mark E. Lender & James K. Martin, editors, Citizen Soldier: The Revolutionary War Journal of Joseph Bloomfield (Newark, NJ: New Jersey Historical Society, 1982), 116.

[27] Entry for Francis Barber, Frances B. Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army During the War of the Revolution, April, 1775, to December, 1783, Reprint of the New, Revised, and Enlarged Edition of 1914, With Addenda by Robert H. Kelby, 1932 (Baltimore MD: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1982), 86. Barber would be wounded at Monmouth, Newtown, and Yorktown. He would be tragically killed by a falling tree in February 1783.

[28] Lender & Martin, Citizen Soldier, 116, entry for November 20, 1776.

[29] Elmer, Journal, 42, entry for November 20, 1776.

[30] Entry for Anthony Walton White, Heitman, Historical Register of Officers, 585.

[31] Entry for Anthony Walton White, Francis J. Sypher, Jr., New York State Society of the Cincinnati: Biographies of Original Members & Other Continental Officers (Fishkill, NY: New York State Society of the Cincinnati, 2004), 578-580.

[32] Entries for Aaron Burr, Alexander Hamilton, and Richard Varick, Francis J. Sypher, Jr., New York State Society of the Cincinnati, 61-65, 200-603, and 552-555.

5 Comments

Well done, Phil! As usual, great research and superb writing! Looking forward to your next article!

Joe Cerreto

Phil,

Well researched and very interesting article. Enjoyed it! Keep writing!

excellent and enjoyable article. Give one a picture of the personalities of the leadership of the Regiment and their quirks……

Thank you gentleman, for your kind comments. They are greatly appreciated.

“Outside of a passing mention of the initial assault, there appears to be nothing in contemporary documents confirming the incident.”

White’s assault on Varick is also noted in Joseph Bloomfield’s diary, in the entry dated Nov. 18, 1776: “Early this Morning Lieut. Col. White drew his sword on Capt. Varick & was ordered under an arrest.”