On March 14, 1778, Gen. George Washington sent the following recommendation to Congress concerning Brig. Gen. Casimir Pulaski, who on February 28 had resigned as Commander of Horse:

The Count, however, far from being disgusted with the service, is led by his thirst for glory, and zeal for the cause of Liberty, to solicit farther employment, and waits upon Congress to make his proposals.

. . . P.S. – It is understood, that the Count expects to retain his rank as Brigadier, and I think, is entitled to it from his general character and particular disinterestedness in the present occasion.[1]

One of the “proposals” that Pulaski planned was to form an independent unit of both infantry and cavalry, known during the American Revolution as either a legion or partisan corps.[2] So with the burdens of commanding a non-existing cavalry corps behind him, Pulaski began the second phase of his service in the Continental Army.

The Board of War and Congress took Washington’s recommendation into consideration and on March 28, 1778, formally approving the formation of the Pulaski Legion:

That Count Pulaski retain his Brigadier in the army of the United States and that he raise and have command of an independent corps to consist of sixty-eight horse and two hundred foot, the horse to be armed with lances, and the foot equipped in the manner of light infantry; the corps to be raised in such way and composed of such men as General Washington shall think expedient and proper; and if it shall be thought by General Washington that it will not be injurious to the service, that he have the liberty to dispense, in this particular instance, with the resolve of Congress against inlisting (sic) deserters.[3]

The change in Pulaski’s status was even noted by the British forces, particularly by the Hessians, as Adjutant General Major Carl Baurmeister reported:

In Jersey only the back of the Delaware is occupied by levies, for Gov. Livingston can raise only a few militia. Pulaski is no longer in Trenton. He is engaged in raising a volunteer corps of six hundred men, for whom the war council granted only arms for two hundred and forty horses. Their food and pay they must get through their own bravery.[4]

With this approval of Congress, Pulaski, who had been in York, Pennsylvania where Congress was meeting since the evacuation of Philadelphia in the autumn 1777, went to Baltimore where he established the official headquarters of the Legion.[5] While the Legion was headquartered in Baltimore, other recruiting sites were established in Wilmington, Trenton, Easton, Albany, Boston and Virginia.[6] Pulaski thought that he was given a free hand to raise, train and employ the Legion as he saw fit. So he enthusiastically set out to fill in the ranks of his Legion with fighting men; however this enthusiasm was eventually going to lead him to clash with both Congress and Washington.

Congress initially issued a $10,000 warrant “. . . for the purpose of purchasing horses and recruiting his corps.”[7] On April 6, 1778 they authorized another $50,000 to be available to train and equip the Legion. Due to the devaluation of the Continental dollar and inflation, Pulaski ran short of funds before the Legion was fully equipped and on August 20, 1778 another $17,786 was authorized.[8] In the original appropriation Congress allotted $130 per Legionnaire and detailed how they were to be outfitted:

For each cavalryman and light infantry soldier, one stock, one cap, a pair of breeches, one comb, two pairs of stockings, two pairs gaiters, three pairs shoes, one pair buckles, a spear and a cartouch (sic) box: For each trooper, a pair of boots, a saddle, halters, curry-comb and a brush portmantle, picket cord, and pack saddle.[9]

In John Mollo’s, The Uniforms of the American Revolution, he gives us a description of how Pulaski Legionnaire was outfitted:

Clothing returns for the years 1778-1780 reveal that both the cavalry and infantry of the Legion were issued with cavalry type helmets and blue coats faced with red. The cavalry, however, seem to have worn more conventional jackets or sleeved waistcoats, buckskin breeches and boots, when on active service.[10]

Brigadier General Pulaski was given authority to select his own officers. As would be natural for a man in his position, he turned to those he knew and understood, with the result that his officer corps was mostly foreigners.[11] However, as Jan S. Kopczewski noted, the Legion’s rank and file “was composed of representatives of various nationalities: Americans, Frenchmen, Poles, Irishmen, and Germans, the latter (mainly deserters from Hessian mercenary units fighting in the British army) being the most numerous.”[12] Aiding him in his recruiting efforts was the designation that the Legion was part of the Continental Army and therefore would qualify enlistees for both the Continental bounty and any state bounty. The recruits would be credited to the states towards their quotas.[13]

For the next five months, Pulaski and a cadre of officers traveled throughout the Delaware Valley, Maryland and beyond looking for legionnaires and equipment. An advertisement in the New Jersey Gazette described the mission of the Legion and gave a call for volunteers:

Congress having resolved to raise a Corps consisting of Infantry and Cavalry, to be commanded by General count PULASKI. All those who desire to distinguish themselves in the service of their Country, are invited to enlist in that corps, which is established on the same principles as the Roman Legions were. The frequent opportunities which the nature of the service of that corps will Offer to the enterprising, brave, and vigilant soldiers who shall serve in it, are motives which ought to influence those who are qualified for Admission into it, to prefer it to other corps not so immediately destined to harass the enemy; and the many captures which will infallibly be made, must indemnify the legionary soldiers for the hardships they must sustain, and the inconsiderable sum given for bounty, the term for their service being no longer than one year from the time that the corps shall be completed. Their dress is calculated to give a martial appearance, and to secure the soldier against the inclemency of the weather and season. The time for action is approaching, those who desire to have an opportunity of distinguishing themselves in that corps, are requested to apply to Col. Kowatch at Easton, to Major Julius, count of Mont-fort, at head-quarters, or at Major Betkins quarters at Trenton.[14]

Even with the call for men who understood both the rigors and rewards of being a member of the Legion, Pulaski encountered one of the same problems that plagued the American army in general: desertion. The following notice appeared in the New Jersey Gazette on July 15, 1778:

Deserted from the subscriber 20th of June, a certain Andrew Nelson, belonging to General Pulaski’s Legion, about 18 years of age, five feet six inches high, has black hair and eyes. He is supposed to be in the pines near Imlay’s Town making tar, or at the saltworks in Monmouth. Whoever takes him up and delivers him to the keeper of Trenton gaol, shall receive SIX DOLLARS reward and reasonable charges, paid by

Henry Bedkin, Major in Count Pulaski’s Legion[15]

Pulaski ran into problems with his recruiting efforts. He was accused of taking men already on the rolls of other regiments, enlisting more Hessian deserters than he was supposed to, and taking in prisoners of war from the British army.[16] Initially, Washington permitted Pulaski to draft, or take, two privates of his own choice from each of the four regiments of horse and one sergeant from Sheldon’s regiment, along with their horses, arms and accoutrements.[17] Pulaski then requested that he be allowed to select an additional four men from each regiment but Washington refused: “ . . . I am sorry It is not in my power to grant your request relative to draughting four men per Regiment for your Corps, as this would be branching ourselves out into different corps without increasing our strength—and men cannot conveniently be spared from the line at present.”[18]

Pulaski received another rebuke from Washington due to his taking men already committed to other regiments:

Head Quarters, June 13, 1778.

Sir: His Excellency having been informed by General Smallwood, that some of the Officers in your Legion have inlisted several men out of the Draughts and recruits belonging to Maryland, It is order, that every man so inlisted be immediately returned and delivered to General Smallwood or any officer of the Maryland Troops. I am etc.[19]

Pulaski also came into conflict over his recruiting methods when he enlisted deserters and prisoners of war.[20] In the May 1, 1778 letter Washington further rebuked Pulaski for irregularities with his recruiting:

I am exceedingly concerned to learn that you are acting contrarily both to a positive Resolve of Congress and my express orders, in engaging British prisoners for your Legionary Corps—When Congress refered you to me on the subject of its composition, to facilitate your raising it I gave you leave to enlist one third deserters in the foot, and was induced to do even that from your assuring me that your intention was principally to take Germans, in whom you thought a greater confidence might be placed—The british Prisoners will chearfully enlist as a ready means of escaping, the continental bounty will be lost and your Corps as far as ever from being complete—I desire therefore that the prisoners may be returned to their confinement and that you will for the future adhere to the restrictions under which I laid you—the horse are to be without exception natives who have ties of property and family connexions— I am Sir Your most obedt Servt.[21]

Fred A. Berg noted the following concerning Pulaski’s recruiting methods: “George Washington had allowed Pulaski to recruit up to a third of his infantry from German deserters, but Pulaski recruited anyone who came forward in the true ‘freikorps’ tradition. There were British deserters among the cavalry, much to Washington’s displeasure.”[22]

It was at this time that a Pulaski legend was born. It involved the banner of the Pulaski Legion and the so-called Moravian “nuns” or “sisters” of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. On April 16, 1778 (Holy Thursday), Pulaski, accompanied by his commander of the Legion’s cavalry, Colonel Kowatz, attended services at the Moravian church, and again in May.[23] The legend developed that in return for Pulaski’s chivalric action of placing a guard at the entrance to the Sister’s House to protect it from unruly troops, they presented Pulaski with an embroidered silk banner that became the standard of the Pulaski Legion. The episode was immortalized in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem Hymn of the Moravian Nuns of Bethlehem at the Consecration of Pulaski’s Banner, in which Longfellow related how this religious order presented Pulaski with a flag in which he was eventually wrapped when he was mortally wounded in Savannah.[24] In reality the Moravian “Nuns” were not a religious order but the unmarried women of the community, and Pulaski commissioned the women to sew a standard. It was not a large flag but an eighteen-inch square guidon described as follows:

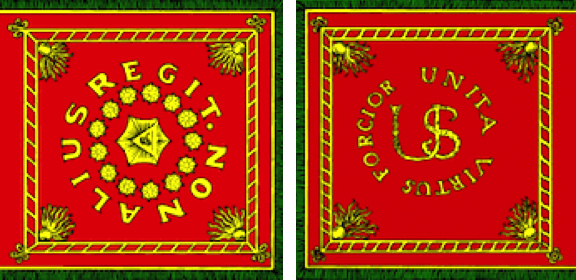

The original is at the Maryland Historical Society. The standard is eighteen inch square with deep green bullion fringe, originally silver and has a sleeve for its staff. The field is made of two layers of crimson silk, (now faded) with emblems embroidered in yellow silk. The obverse side of the flag shows a brown “All Seeing Eye” within a circle of thirteen eight pointed stars surrounded by the motto “NON ALIUS REGIT” (No Other governs). … The reverse side has the letters “U S” encircled with the motto, “UNITAS VIRTUS FORCIOR” (Union Makes Valor Stronger). In the corners are exploding hand grenades depicted in yellow and white thread.[25]

While Pulaski was in the midst of training his legion, the British evacuated Philadelphia. The last major battle in the northern theater of operations took place in late June 1778 at Freehold, New Jersey (the Battle of Monmouth). Clarence Manning stated that Pulaski was affected by the outcome of the battle and his not being present:

Pulaski was furious that he had not been present and he groaned as he realized that proper use of the cavalry might have swayed the course of the battle. Even one charge by a few well-trained troops would have done wonders for the Americans. It inspired him to new efforts and it drove him to still more strenuous attempts to secure needed supplies.[27]

However, Capt. Johann Ewald, a Hessian officer with the Jaeger Corps, placed Pulaski at the scene on June 27 he noted: “About midday the Marquis de Lafayette and count Pulaski appeared; the latter commanded the advance guard yesterday . . .” and on July 2 ” . . . that he (Washington) had pushed three corps under Generals Lafayette, Pulaski and Morgan against us in order to make our crossing at Sandy Hook more difficult.” [28] So was Pulaski at the Battle of Monmouth? Ewald is the only one to make a reference of his being at Freehold. There is no documentary evidence of his actual whereabouts for this time frame. He most likely was in the area recruiting and training his Legion. Might he have heard of the impending battle and joined Lafayette on his own, as he did at Brandywine? Pulaski was well known by the Hessian officers and it would be strange that Ewald would single him out for mention in his diary if he were not there. But again, this is the only reference to Pulaski’s presence.

By July 1778, Pulaski completed the recruiting and training of his Legion. He was originally authorized to field a complement of 268 troops, of which 68 were to be light dragoons, but he ended with a total of 330 men. According to Berg, the organization of the Legion in the Autumn 1778 was: “A staff, three troops of cavalry, one company of riflemen (chasseurs), a grenadier company, two infantry companies and a supernumerary company. Each company and troop consisted of 25-30 men.”[29] At their headquarters in Baltimore the first formal review of the Legion took place. The Maryland Journal and Baltimore Advertiser of Tuesday, August 4, 1778, reported on it:

On Wednesday last (July 29th), the Hon. General Count Pulaski, reviewed his Independent Legion in this Town. They made a martial appearance and performed many Manoeuvers in a Manner that reflected the highest Honour on both officers and privates.[30]

At the end of August, all elements of the Legion rendezvoused at Wilmington, Delaware. Eager to take the field with his legion, Pulaski was frustrated that Congress still had not given approval for the activation of his troops. In September 1778, Pulaski brought the Legion to Philadelphia to be reviewed and inducted into the Continental Army. Having passed the review, Pulaski’s frustration and anger increased as the Legion was detained in Philadelphia due to questions that the Board of War had concerning alleged irregularities with the Legion’s records and accounts. Some of Pulaski’s resentment comes through in a letter sent to Congress on September 17:

. . . I blush tho to find my Self languishing in a state of inactivity, animated with the zeal of serving ye, and the support of my reputation, urged me, gentlemen, to write ye. The request I now make is by due, ye permitted me to rease a Corps of partisans, my privilege is to be directed by experience for the most useful measures. . . .[31]

With approximately two months remaining in the campaign season of 1778, Washington on September 19, 1778 sent Pulaski orders to move to the Hudson River at Fredericksburg, but only after he received approval from Congress.[32] Then on the 29th he redirected Pulaski to take the Legion to Paramus, New Jersey and place himself under the command of Major General Lord Stirling, “. . . As the enemy are out in considerable force in Jersey.”[33] The next day, Congress ordered, “That Count Pulaski, with his legion and all Continental soldiers fit for service in and near Philadelphia, be directed to repair immediately to Princeton, there to wait the orders of General Washington, or the commanding officer in New Jersey.”[34] Pulaski sent the infantry companies on their way, but he received another blow when, on October 2, 1778, Congress ordered him to appear personally before the Board of War to answer charges lodged against him by Justice McKean of Pennsylvania, accusing him of “resisting civil authority.” There is a description of this event in a letter by Samuel Adams to James Warren dated October 20, 1778:

I will finish this Scrawl with an Anecdote. Not many Days ago a Sheriff of the County of Philadelphia attempted to Serve a Writ on the Person of count Pulaski. He was at the Head of his Legion and resisted the officer. A representation of it was made to Congress by the Chief Justice who well understands his Duty and is a Gentleman of spirit. The count was immediately ordered to submit to the Magistrate, and informed that congress was determined to resent any Opposition made to the Civil Authority by any of their officers. The count acted upon the Principles of Honor. The Debt was for the Support of his Legion, and he thought the Charge unreasonable as it probably was. He was ignorant of the Law of the land and made the Amend honorable. The board of War afterward adjusted the Account and the Creditor was satisfied.[35]

Along with this, there is an interesting sidelight to Pulaski’s stay in Philadelphia. While awaiting activation, in light of the frustration, rancor and antagonism that developed between him and Congress was a report published a few weeks later in Rivington’s New York Royal Gazette. In it Pulaski became the centerpiece in the British propaganda war; supposedly a member of Congress gave a speech calling for the repeal the Declaration of Independence when:

. . . He had scarcely uttered the words before the President sent a message to fetch the Polish count, Pulaski, who happened to be exercising part of his legion in the courtyard below. The Count flew to the chamber where the Congress sat, and with his saber, in an instant severed from his body the head of this honest delegate. The head was ordered by the Congress to be fixed on top of the liberty pole of Philadelphia, as a perpetual monument of the freedom of debate in the Continental congress of the Untied States of America.[36]

Finally after a hearing on Saturday, October 3, 1778, Pulaski received the orders he was waiting five months for when Congress “Resolved, that the Legion, under command of Count Pulaski, be ordered to proceed immediately to assist in the defence of Little Egg Harbor against the attack now made by the enemy on that part.”[37]

After all the time and money that went into the forming of Pulaski Legion, neither they nor their Commander fared well. On October 15, 1778 there occurred what has been called the “Massacre of the Pulaski Legion” or “The Affair at Egg Harbor” where approximately forty to fifty Legionnaires were killed by a surprise night attack by British forces led by Capt. Patrick Ferguson at the Jersey Shore. Following this fiasco, the Legion was sent to northwestern New Jersey, the tri-state area on the Delaware River known as the “Minisinks,” where Pulaski complained that he had nothing to fight but “bears.”[38] At this point Pulaski seriously considered returning to Europe, however the change in the focus of the war to the Southern States gave Pulaski a renewed interest in the War of Independence and he led the Legion south to his ultimate destiny.

[1]Washington to President of Congress, March 14, 1778, in Worthington Chauncey Ford: The Writings of George Washington, vol. VI (1777-1778) at http://oll.libertyfund.org

As to what led to his resignation see: Joseph Wroblewski, “The Winter of His Discontent: Casimir Pulaski’s Resignation of Horse,” Journal of the American Revolution, November 14, 2016.

[2]The designation legion or partisan corps was used interchangeably for various units in the Continental Army. It referred to “A body of special troops intended for raiding and reconnaissance.” For a description of these units see: Fred A. Berg, Encyclopedia of Continental Army Units (Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1972), 101.

[3] Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed. vol. X, 291, https://archive.org/stream/journalsofcontin. Hereafter JCC.

[4] Carl Baurmeister, Revolution in America, Confidential Letters and Journals 1776-1784 of Adjutant Major General Baurmeister of the Hessian Forces, Bertram A. Uhledorf, ed. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Press, 1957), 165.

[5]Pulaski initially intended to call it the Maryland Legion, but in the spirit of most “freikorps” it was known by the name of its founder.

[6] Francis Kanjencki, The Pulaski Legion in the American Revolution (El Paso: Southwest Polonia Press, 2004), 82.

[7] JCC, X, 300.

[8] JCC, XI, 491. On May 11, 1778 Congress ordered the first installment of $16,000 and on May 27, the final $24,000. JCC, XI, 538, 824.

[9] JCC, X, 312. “Portmantle” was most likely “portmanteau,” a case for carrying clothes on a horse.

[10]John Mollo, Uniforms of the American Revolution, Malcolm McGregor, illustrator (London: Blanford Press, 1975), 212.

[11] JCC X, 364. The first officer appointments to Pulaski’s Legion approved by Congress were “… Michael de Kowatz be appointed colonel commandant; Count Julius de Mountfort, major; John de Zielinske (sic) captain of lancers.”

[12] Jan S. Kopczewski, Kosciuszko and Pulaski (Warsaw, Poland: Interpress, 1976), 129. For a complete roster of the Pulaski Legion, both officers and enlistees see: Richard Henry Spencer, “Pulaski’s Legion,” Maryland Historical Magazine, vol. XIII, 220-226, online at MSA. Maryland.org.). Also Kanjecki, The Pulaski Legion, Appendix F, “Muster Rolls of the Pulaski Legion,” 317-339.

[13] JCC, X, 312; “In CONGESS April 6, 1778, ‘THAT if any of the states in which Brigadier General Pulaski shall recruit for his Legion, shall give to persons enlisting in the same for three years or during the war, the bounty allowed by the state, in addition to the Continental bounty, the men so furnished, not being inhabitants of any other of the United States, shall be credited to the quota of the state in which they shall be enlisted.”

[14] New Jersey Gazette, April 21, 1778, in New Jersey Archives Newspaper Extracts, 2nd Series, vol. II, 1778, Francis B. Lee, ed.” (Trenton, NJ: John L. Murphy, 1903), 183-184. The same advertisement appeared in the Maryland Journal and Baltimore Advertiser, April 14, 1778, Maryland Historical Magazine, vol. XIII, 216.

[15] New Jersey Gazette, July 1778, in New Jersey Archives Newspaper Extracts, 299.

[16] Martin Griffin, Catholics in the American Revolution, v: III (Philadelphia, 1911),

65-67.

[17] George Washington, The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources 1745-1799, v. 11: March 1, 1778-May 31, 1778, John C. Fitzpatrick, editor (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1934), 230, Babel.hathitrust.org.

[18] Washington to Pulaski, May 1, 1778, Founders Online, National Archives, http://founders.archives.gov/; original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 15, May–June 1778, ed. Edward G. Lengel (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006), 7.

[19] The Writings of George Washington, v. 12 June 1, 1778-September 30, 1778, 55.

[20] For an interesting presentation on the controversy of Pulaski’s recruiting deserters and prisoners, see Leszek Szymanski, Casimir Pulaski: A Hero of the American Revolution (New York: Hippocene Books, 1994), 160-171.

[21] Washington to Pulaski, May 1, 1778.

[22] Berg, Encyclopedia of Continental Army Units, 101.

[23]Colonel Michael Kovats de Fabriczy, Hungarian cavalry officer who Pulaski recommended to Washington to be his Commandant of Horse, was killed at the Battle of Charleston, May 11, 1779.

[24]Complete text of the Longfellow poem can be found in either Griffin, Catholics in the American Revolution, 63-64; or Kanjecki, The Pulaski Legion, 94.

[25]Edward W. Richardson, Standard and Colors of the American Revolution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1982), 52-53.

[26]The original banner was donated to the Maryland Historical Society by a Pulaski Legionnaire, Capt. Paul Bentalou. Images created by Randy Young, September 2004 as found on Flags of the World website.

[27] Clarence Manning, A Soldier of Liberty: Casimir Pulaski (New York, NY: Philosophical Librarym 1945), 258.

[28] Johann Ewald, Diary of the American War: A Hessian Journal, Joseph Tustin, ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 135. It should be noted that the editor (Tustin) in footnote 54 (403) stated the person heading the “advanced guard” was really Col. Stephen Moylan who took command of the Continental Calvary after Pulaski’s resignation.

[29] Berg, Encyclopedia of Continental Army Units, 101.

[30] Maryland Historical Magazine, vol. XIII, 217.

[31] Griffin, Catholics in the American Revolution, 67.

[32] Washington to Pulaski, September 19, 1778,” http://founders.archives.gov/

[33] Washington to Pulaski, September 29, 1778,” http://founders.archives.gov/. Most likely what provoked this order was the “Baylor Massacre” when on September 27, 1778 the 3rd Continental Dragoons were surprised in a night bayonet attack led by Gen. Charles Grey at Old Tappan, New Jersey. At least sixty-nine Continentals were killed, wounded or captured. Colonel Baylor himself was wounded and taken prisoner.

[34] JCC, XII, September 30, 1778, 969.

[35]Letters of Members of the Continental Congress, vol. III, Edmund C. Burnett, ed. (Gloucester, MA: 1963 reprint), 458-459.

[36]Frank Moore, Diary of the American Revolution from Newspaper and Original Documents, vol. II (New York: Charles Scribner, 1859), 101, online at arhives.org.

[37] JCC XII, 983-984.

[38]Kajencki, The Pulaski Legion, 130.

Recent Articles

The Sieges of Fort Morris, Georgia

This Week on Dispatches: Scott Syfert on the Mecklenburg Declaration

Richard Cranch, Boston Colonial Watchmaker

Recent Comments

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

I am not sure I will ever be convincingly swayed one way...

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

Interesting! Thanks, from a Charlotte NC Am Rev fan.

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

A great overview of that controversial document. I tend not to accept...