It is not often the site of a Revolutionary War battle is rediscovered. It is even more unusual that the probable site is in between New Jersey’s largest trash dump and the loud rushing traffic of its most crowded highway. New research indicates that the site of the Battle of Bennett’s Island is either just inside, or on a rise of land just west of, the Edgeboro Landfill and immediately east of the New Jersey Turnpike (Exit 9 on Route 95) in East Brunswick Township in Middlesex County.

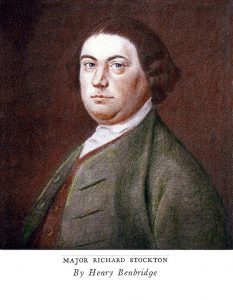

On February 18, 1777, New Jersey militia colonel John Neilson led about 150 militiamen and 50 Pennsylvania riflemen on a surprise pre-dawn raid of Bennett’s Island, located on the Raritan River to the southeast of then British-held New Brunswick. The raid resulted in the capture of Major Richard Stockton, renowned as the “land pilot” for guiding British forces across New Jersey, as well as three other officers and sixty soldiers of the New Jersey Volunteers, a Loyalist regiment. Four of Stockton’s soldiers were killed in the raid, while Neilson lost only one man. The raid also permitted Colonel Neilson and his Middlesex County militia to impede British vessels attempting to supply New Brunswick.

I had become aware of this interesting military engagement as a result of covering Richard W. Stockton in one of my prior books on kidnapping attempts, but researcher extraordinaire Chris Hay of Maple Ridge, British Columbia, Canada, had studied the Battle of Bennett’s Island in great detail and was gracious enough to share his research discoveries with me. Chris is a descendent of Stockton (a fifth great grandson).

The hero of the raid was an enterprising militia officer, Col. John Neilson of the 2nd Regiment of Middlesex County militia. Born March 11, 1745 at Raritan Landing, his family had emigrated from Belfast, Ireland. He was raised by an uncle, James Neilson, a successful New Brunswick merchant. Neilson graduated from what is now the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and then joined his uncle’s mercantile business. Commissioned a colonel of a regiment of Middlesex County minutemen in August 1775, a year later he became colonel of the county’s 2nd Regiment of militia.[1] On July 9, 1776, Neilson gave one of the earliest readings of the Declaration of Independence, standing on a table before a crowd in front of a New Brunswick tavern on Albany Street.[2]

The story of the battle starts with the stunning victories by George Washington and his Continental Army at Trenton on December 26, 1776, and at Princeton on January 3, 1777. Having inflicted two embarrassing defeats on the British army commanded by Gen. William Howe, Washington departed Princeton and marched his army north toward Morristown, where he would spend the winter.[3]

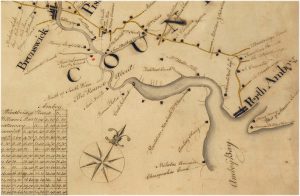

Meanwhile Howe ordered his army to retreat from Princeton to New Brunswick, abandoning several posts in New Jersey.[4] With campaigning season over due to winter conditions, Howe’s ten thousand British, German and Loyalist troops were soon crammed in towns and villages from Perth Amboy—at the mouth of the Raritan River—to New Brunswick about thirteen miles to the west. Most were stationed in New Brunswick, consisting of about four hundred houses. All of the main posts were to the north of the Raritan River.[5]

The American victories at Trenton and Princeton reinvigorated the New Jersey militia, which had virtually collapsed and disbursed in many places after British advances in the state in November and December of 1776. On December 31, General Washington ordered Col. John Neilson, along with Maj. John Taylor of his regiment and three other New Jersey militia officers, then with the main army west of the Delaware River, to return to their home state to “call together and embody” its militia.[6] Militiamen were drafted in Middlesex County and adjoining counties. Soon British foraging parties of 500 to 600 men were constantly harassed not only by Continentals, but also by New Jersey militia, which often inflicted substantial casualties.[7]

The American victories at Trenton and Princeton reinvigorated the New Jersey militia, which had virtually collapsed and disbursed in many places after British advances in the state in November and December of 1776. On December 31, General Washington ordered Col. John Neilson, along with Maj. John Taylor of his regiment and three other New Jersey militia officers, then with the main army west of the Delaware River, to return to their home state to “call together and embody” its militia.[6] Militiamen were drafted in Middlesex County and adjoining counties. Soon British foraging parties of 500 to 600 men were constantly harassed not only by Continentals, but also by New Jersey militia, which often inflicted substantial casualties.[7]

Eventually, by January 25, Neilson gathered about 175 militiamen for his 2nd Regiment of Middlesex County militia, but 60 of them lacked muskets. Neilson took post at Cranbury, New Jersey, about seven miles north of Princeton and fifteen miles south of Bennett’s Island.[8] The thirty-two-year-old Neilson likely heard the rumors that General Howe was making as his New Brunswick headquarters Neilson’s fine house on Burnet Street.

British commanders worried that American artillery, if well posted on heights overlooking the Raritan River, could impede supply ships attempting to pass to the west from Perth Amboy to New Brunswick. In particular, the so-called Roundabout, where the Raritan River flowed in a narrow channel in a bend past a wooded point near the mouth of the South River, was an ideal place for the Americans to place artillery.

Realizing British supply boats slowly navigating the river at this narrow bend were vulnerable, the senior general of the Continental Army in New Jersey, Maj. Gen. Israel Putnam, stationed at Princeton, on February 3 ordered “50 good Riflemen” from Princeton to the Roundabout “to annoy the enemy’s boats that are passing and repassing with provisions and stores.”[9] The riflemen, from Bedford County, Pennsylvania, under the command of Captains William Macalevy, William Parker, and Samuel Davidson, were in turn temporarily placed under Neilson’s command.[10]

On February 5, the “very advantageously placed” riflemen spotted a boat coming down the river from Brunswick with about twelve men on its deck. According to their officers’ report to General Putnam, twenty-five Pennsylvania sharpshooters “gave them a how do you do . . . But we cannot say we killed more than three that was seen laying on the deck . . . .”[11]

In response to this threat of interfering with British shipping between Perth Amboy and New Brunswick at the Roundabout, and with Howe absent at the time, Gen. Charles Cornwallis or one of his subordinates ordered that a new post be occupied at the heights on the river, at a place called Bennett’s Island, overlooking a bend in the Raritan just north of the Roundabout. The order was likely given to Brig. Gen. Cortland Skinner, a former attorney general of New Jersey and the commander of the New Jersey Volunteers. Skinner, in turn, ordered Maj. Richard Stockton and one hundred soldiers of the same Loyalist corps to occupy Bennett’s Island.[12] From there, Stockton and his men would discourage attempts by the Americans to place artillery at the Roundabout. The assignment, however, must have made the forty-two-year-old Stockton blanche, as his lightly defended post would be south of the Raritan and thus exposed to another “Trenton.”

In response to this threat of interfering with British shipping between Perth Amboy and New Brunswick at the Roundabout, and with Howe absent at the time, Gen. Charles Cornwallis or one of his subordinates ordered that a new post be occupied at the heights on the river, at a place called Bennett’s Island, overlooking a bend in the Raritan just north of the Roundabout. The order was likely given to Brig. Gen. Cortland Skinner, a former attorney general of New Jersey and the commander of the New Jersey Volunteers. Skinner, in turn, ordered Maj. Richard Stockton and one hundred soldiers of the same Loyalist corps to occupy Bennett’s Island.[12] From there, Stockton and his men would discourage attempts by the Americans to place artillery at the Roundabout. The assignment, however, must have made the forty-two-year-old Stockton blanche, as his lightly defended post would be south of the Raritan and thus exposed to another “Trenton.”

Richard Witham Stockton of Princeton, New Jersey, a first cousin to the signer of the Declaration of Independence with the identical first and last names, before the war was a successful farmer and an educated man. He was appointed captain of the New Jersey Volunteers in August of 1776, when the unit was stationed on Staten Island and still gathering troops.[13]

Called “Double Dick” by his enemies, Stockton’s true calling was as a skilled guide, which also earned him a more complimentary sobriquet, the “renowned Land Pilot.”[14] Indeed, Stockton may have earned his title by serving as the key guide for Lt. Col. William Harcourt and a small party his 16th Regiment of Light Dragoons in the capture of Maj. Gen. Charles Lee of the Continental Army at Basking Ridge, New Jersey, on December 13, 1776, and the party’s safe return to Pennington the same day. This episode, and Stockton’s possible involvement, is detailed in one of my prior books, but it was only in my most recent book, with the key assistance of researcher Chris Hay, that Stockton was identified with certainty as the main guide for Harcourt’s party.[15] Given that the capture of Lee—second in command of the Continental Army to only General Washington and its most experienced general—was considered a tremendous coup in the British army (and in London when the news arrived there), Stockton basked in the shared glory. As a result of guiding Harcourt’s party, while still at Pennington in December 1776, General Skinner promoted Stockton to the rank of major of the 6th Battalion of New Jersey Volunteers.[16]

Stockton was probably assisted in acting as a guide in Lee’s capture by Capt. Asher Dunham of Morris County, New Jersey, also of the New Jersey Volunteers. After joining Skinner’s Brigade at New Brunswick in November of 1776, Dunham claimed in his post-war application for reimbursement of losses that he “was at that time frequently employed by General Skinner and others to procure information for the Royal Army” and that “he was in the country on that service at the time Colonel Harcourt took the Rebel Major General Lee, and did actually join him on that occasion.”[17] Dunham presumably did not claim he was the lead guide, as that role was Stockton’s.

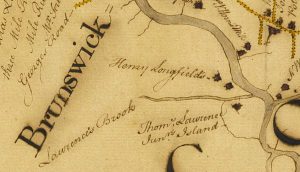

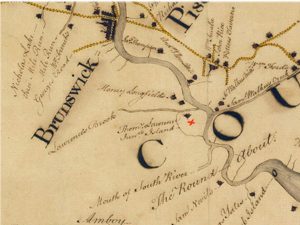

The post Major Stockton was ordered to hold, Bennett’s Island (also called Lawrence Island, after one of its first settlers in the late seventeenth century, Thomas Lawrence), was located about three miles southeast of New Brunswick on the Raritan River. Stockton commanded only Captain Dunham, four subalterns, and about one hundred privates from the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 6th Battalions of the New Jersey Volunteers.[18] While the post was hidden inside swamps and woods, and was surrounded by the Raritan River to the north, the South River to the east, and the Lawrence Brook to the west, it was still exposed to attack.

Most of Bennett’s Island consisted of productive riverside farmland, including the two-hundred acre Island Farm. This farm contained a fine residence—a shingled, two-story house with two kitchens that was forty feet wide and twenty feet deep—on a height of land with a view of the Raritan River and Perth Amboy in the distance, in addition to “a good dairy house,” an “old barn,” and a “good wagon house.”[19] Stockton and his officers made the main house on Bennett’s Islands both their headquarters and sleeping quarters.

The British were not the only side suffering casualties in the forage war. On February 14, Gen. David Foreman of the New Jersey militia informed Neilson that in the morning, a British force had attacked and “cut off” New Jersey militia posted to guard Sandy Hook off Lower New York Bay. About sixty men were captured, Foreman reported, but only a few were killed.[20] Neilson was on the lookout for a retaliatory raid.

On or around February 17, one of Major Stockton’s soldiers deserted and was brought to Colonel Neilson at Cranbury. This unidentified deserter turned out to be a former American soldier who informed Neilson he had served at Fort Washington on Manhattan Island in a Pennsylvania regiment when it fell to the British army in November 1776, had enlisted in the British army rather than endure the horrors of a British prison, and had finally found his opportunity to escape when Stockton’s party took its post at Bennett’s Island.[21] The deserter further informed the local Patriot commander of the defenses and other details of the Bennett’s Island outpost, including locations of the guards. The deserter probably also advised that the British had another guard of sixty soldiers located about one-half a mile to the west of Bennett’s Island across Lawrence Brook to the north at Henry Longfield’s farm.[22] Neilson trusted the two-time deserter.

Immediately seizing the initiative, at his headquarters at Cranbury, Neilson began planning for that very evening making a night time march to Bennett’s Island followed by a surprise attack on Stockton and his force. After a messenger informed General Putnam of the plan and requested reinforcements, the Connecticut-raised Continental general responded by promptly sending Neilson the same fifty riflemen from Bedford County, Pennsylvania, who had ambushed the British boat at the Roundabout. These reinforcements arrived later the same day at Cranbury, with a message from Putnam to Nielson: “I am pleased at your forming a party against Stockton & wish them success.”[23]

Immediately seizing the initiative, at his headquarters at Cranbury, Neilson began planning for that very evening making a night time march to Bennett’s Island followed by a surprise attack on Stockton and his force. After a messenger informed General Putnam of the plan and requested reinforcements, the Connecticut-raised Continental general responded by promptly sending Neilson the same fifty riflemen from Bedford County, Pennsylvania, who had ambushed the British boat at the Roundabout. These reinforcements arrived later the same day at Cranbury, with a message from Putnam to Nielson: “I am pleased at your forming a party against Stockton & wish them success.”[23]

Neilson apparently briefed his officers and perhaps even their men on the goals of their march. In his pension application filed after the war, Isaac Covenhoven, a private in Neilson’s regiment, recalled that the men were to disarm Tories at Bennett’s Island, make a prisoner of Major Stockton and deliver him to headquarters.[24] At sunset Neilson ordered his men to begin their march, guided by Andrew McDowell. While it was a brisk night, and the ground was covered in snow, no storm threatened and the Patriot troops made good time.[25]

Neilson’s men marched to David Williamson’s tavern and rested there until 11:00 p.m. From there, they marched on to “old Ogden’s,” located on the South River about one mile south of Bennett’s Island and the probable family home of Benjamin Ogden, a young private in the raiding party. After waiting for the moon to go down, when it became “very dark,” at 4:00 a.m. Neilson ordered his men to carry on to Bennett’s Island. Colonel Neilson described what happened next:

The main body the moment they got over the causeway at the foot of the hill fronting the house (where we expected to have met with a sentry) rushed up to the house with the utmost expedition in order to surround the house, which was done—piloted by McDowell & Fisher. At the same time, a detachment being riflemen hastened up to the guard house and endeavored to surround them and cut off their communication with the house—piloted by Ogden and a deserter.[26]

Neilson’s dawn attack achieved a complete surprise. Cutlope Hancock, a private recently drafted into Neilson’s regiment, recalled that he and his fellow Middlesex County militiamen at Bennett’s Island, as well as the Bedford County riflemen, “surrounded the house where the enemy was” before the Tory guards could raise an alarm.[27] Another detachment of men, led by Lt. Nathaniel Hunt, the moment they saw the main house was surrounded, hurried to capture a bridge spanning Lawrence Brook, thus cutting off both a potential escape route for Stockton’s men and the path that British reinforcements at Longfield’s farm would have to take to assist them. Back at the main house, Stockton apparently resisted, as he suffered a wound in the attack.[28] Seeing themselves surrounded, outnumbered and with no avenue of escape, Stockton and most of his men surrendered.

A handful of soldiers under Stockton’s command, perhaps thirty, escaped and made their way back to New Brunswick. In addition, a captain with five or six men of the New Jersey Volunteers retreated to a cellar in one of the two dwelling houses and tried to hide there. Neilson’s men discovered the position, but rather than engage in a firefight against a well defended post, or force the Loyalists out by burning down the house, Neilson left them unharmed.[29]

The attackers suffered only one man killed, Pvt. William Soden of the 3rd Regiment of Middlesex County Militia, while Stockton’s force lost four killed, one wounded, sixty-two captured, and arms for sixty-three soldiers.[30] Among the captives were Major Stockton, Captain Dunham, and Lt. Francis Fraser, all of whom were immediately hustled to General Putnam’s headquarters sixteen miles to the south at Princeton, arriving late in the day on February 18.[31]

In his February 19 report to the commander of New Jersey’s militia, Maj. Gen. Philemon Dickinson, Colonel Neilson wrote that his surprise attack “was done with little opposition” and that “our plans succeeded so well—a short engagement of about one minute decided the matter.” He commended Maj. William Scudder of the 3rd Regiment, second in command and the owner of several mills near Princeton, who “behaved in a very soldierlike manner, and executed his orders with the utmost punctuality and firmness.”[32] Presumably, Scudder led the attack on the main house at Bennett’s Island. (His brother, Dr. Nathaniel Scudder, was killed in a skirmish with a British foraging party on October 17, 1781, the only delegate of the Continental Congress to die in battle during the Revolutionary War.)

One story—unconfirmed by contemporary documents—passed down in Neilson’s family was first published in 1833, in an obituary for Neilson by his son-in-law, A. R. Taylor, who wrote:

Colonel Neilson narrowly escaped with his life. Being one of the first to leap the stockade, a sentinel pressed his gun against his breast, while at the same instant Captain Farmer, a true New Jersey blue, flourished his sword over his head, exclaiming “throw up your gun you damn’d scoundrel, or I will cut you down.” The man being intimidated, obeyed, and the Colonel escaped unhurt.[33]

It appears that the two-time deserter who had alerted Neilson about Stockton’s presence at Bennett’s Island and had served as a guide to the riflemen during the raid, was not punished for enlisting in the British army. In his report to General Putnam, Neilson praised the deserter as “particularly deserving notice.”[34]

General Washington was pleased with the news of Neilson’s success, which likely arrived at his headquarters on February 19 in a letter from General Putnam probably penned by his aide-de-camp, twenty-one year-old Maj. Aaron Burr.[35] In the same February 20 letter read to Congress in which Washington warned of “the weak and feeble state of our little army,” he added the good news of Neilson’s small victory at Bennett’s Island. He wrote that Neilson’s success “about balances the loss of a militia guard, which a party of British troops took last week” at Sandy Hook.[36] He also mentioned the successful raid in a letter written the same day to the New York Convention.[37] In a letter to Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler, Washington wrote that of all the skirmishes with the enemy, the “most considerable that has happened” was Neilson’s raid on Bennett’s Island.[38] The commander in chief further wrote to Israel Putnam on February 20, “The Colonel and his party conducted the plan with such secrecy and resolution that they claim my sincerest thanks for this instance of good behavior, and I wish you would acquaint them with my hearty approbation of their conduct.”[39]

Americans also exulted in the capture of the famous “Land Pilot.” On March 2, 1777, Col. Hugh Hughes, a New York deputy quartermaster general, wrote: “A few days since a part of General Putnam’s division attacked a party of the enemy about three miles from Brunswick and made 60 prisoners, among whom is Stockton who led the party who took General Lee.”[40] At about the same time, a New England newspaper printed the letter of an unidentified American officer, who wrote: “I have the pleasure to acquaint you, that a few days ago a party of General Putnam’s division, attacked and defeated a party of Tory soldiers, in Monmouth, killed a number, and took about 40, with their arms, and one Major Stockton, an infamous Tory who commanded them.” The newspaper’s editors then added in italics, “The above Major Stockton is the identical villain who betrayed his Excellency General Lee into the hands of the enemy.”[41]

Americans also exulted in the capture of the famous “Land Pilot.” On March 2, 1777, Col. Hugh Hughes, a New York deputy quartermaster general, wrote: “A few days since a part of General Putnam’s division attacked a party of the enemy about three miles from Brunswick and made 60 prisoners, among whom is Stockton who led the party who took General Lee.”[40] At about the same time, a New England newspaper printed the letter of an unidentified American officer, who wrote: “I have the pleasure to acquaint you, that a few days ago a party of General Putnam’s division, attacked and defeated a party of Tory soldiers, in Monmouth, killed a number, and took about 40, with their arms, and one Major Stockton, an infamous Tory who commanded them.” The newspaper’s editors then added in italics, “The above Major Stockton is the identical villain who betrayed his Excellency General Lee into the hands of the enemy.”[41]

Once Stockton was identified as the guide who led Harcourt’s party, he and his fellow officers suffered for it. General Putnam gave strict orders to the American officer appointed to conduct the prisoners to Philadelphia that “no indulgence be allowed the villains which affords them a possibility of escape.”[42] This unidentified officer, with or without Putnam’s knowledge (it is not clear), took the unusual and shocking step of having Stockton, Dunham and Fraser manacled together in irons, marched out of Princeton and paraded in Philadelphia as if they were slaves headed towards a slave market.[43] Ending up in a prison in Carlisle, the Loyalist officers were also treated more harshly than the usual captive officers. Stockton was not exchanged until September 1779. But that is a subject for another article. The New Jersey Loyalist later moved to Canada and died in 1801 in New Brunswick at the age of sixty-eight. He is known as the founder of the Stockton family in Canada.[44]

Meanwhile, on February 21, 1777, the hero of Bennett’s Island, John Neilson, was elected by the New Jersey legislature as a brigadier general of the state militia. (Curiously, Nielson always signed his letters as colonel; it does not appear he ever served as a general in the field).[45] Not resting on his laurels, the New Brunswick native quickly followed up on his victory, as his troops were now able to annoy British boats on the Raritan River with virtual impunity. On February 26, a temporary battery of field artillery posted at the Roundabout sunk several boats supporting the British. According to Amos Donnelly, a deserter from a New Jersey Volunteers unit stationed in Perth Amboy brought to Colonel Neilson, the enemy was “very apprehensive & fearful” that the Americans would place a permanent artillery battery at the Roundabouts,[46] but they never did. Eventually, General Howe altered his strategy, deciding to invade Philadelphia by sea. He evacuated New Brunswick on June 22, 1777, and later pulled his forces back from Perth Amboy to Staten Island and Manhattan Island.

After continuing his duties as a colonel of the Middlesex County militia, in 1779 Neilson was elected to the New Jersey general Assembly, and he supervised the building of a number of warning beacons across New Jersey in 1779 and 1780. In September 1780, Neilson was appointed both quartermaster general of the Continental Army and deputy quartermaster general of New Jersey and served in those offices for the duration of the war. After the war, he prospered as a merchant in New Brunswick, living with his wife Catherine Voorhees Neilson, where he died on March 3, 1833.[47] Coincidentally, a new life-size statue of John Neilson was unveiled on July 9, 2017, in New Brunswick at the corner of Livingston Avenue and George Street.

As with any prominent military incident in the war, a number of veterans mentioned the Battle of Bennett’s Island in their pension applications, including Colonel Neilson. It was not uncommon for a few applicants to exaggerate their roles in such prominent military incidents, and thus it is not always easy to separate fact from fiction. Charles Fisher, whom Neilson identified as one of his guides at Bennett’s Island, supplied one such narrative in 1832, more than fifty-five years after the attack. In his pension application, Fisher stated that his father had occupied and farmed all of “Lawrence’s Island” (this claim is supported in the pension application of Jacob Fisher, who said he was born on Bennett’s Island in 1746; Jacob presumably was Charles’s brother).[48] Charles further stated that he “conducted” Neilson’s militiamen and the Bedford County riflemen “on to the island.” While those statements are credible, some of his other statements may not be.

Fisher claimed that, being aware of Major Stockton’s post at Bennett’s Island and the locations of his sentries, he “communicated the plan to Colonel John Neilson” of surprising the Tories. However, Neilson’s contemporary reports credit the deserter from Stockton’s troops with first informing the colonel of Stockton’s post. Fisher further claimed that in the initial stages of the attack on the island, “We stunned [surprised] all the 8 or 9 sentries and the last sentry was killed by a blow” from Fisher himself. He then said that he, along with three or four other men, “took up the bridge to prevent any relief from the British to the island,” meaning from Longfield’s Farm to the west. Apparently everywhere at once, Fisher next claimed that “with his own hands” he disarmed Major Stockton “of his sword by force” and threw him through the window of the main house, “and also threw Dennis Combs and John Grimes, two commissioned officers known to your narrator, through the window.”[49] (As mentioned above, Stockton was wounded in the raid, but it is not known how it happened.) While it is unlikely Fisher did everything he said he did, it is possible he became aware of others doing the deeds and that he participated in a few of them.

Fisher claimed that, being aware of Major Stockton’s post at Bennett’s Island and the locations of his sentries, he “communicated the plan to Colonel John Neilson” of surprising the Tories. However, Neilson’s contemporary reports credit the deserter from Stockton’s troops with first informing the colonel of Stockton’s post. Fisher further claimed that in the initial stages of the attack on the island, “We stunned [surprised] all the 8 or 9 sentries and the last sentry was killed by a blow” from Fisher himself. He then said that he, along with three or four other men, “took up the bridge to prevent any relief from the British to the island,” meaning from Longfield’s Farm to the west. Apparently everywhere at once, Fisher next claimed that “with his own hands” he disarmed Major Stockton “of his sword by force” and threw him through the window of the main house, “and also threw Dennis Combs and John Grimes, two commissioned officers known to your narrator, through the window.”[49] (As mentioned above, Stockton was wounded in the raid, but it is not known how it happened.) While it is unlikely Fisher did everything he said he did, it is possible he became aware of others doing the deeds and that he participated in a few of them.

Where is the location of the Battle of Bennett’s Island? The most likely site is the location of the former main house at the Island Farm within the triangle created by the confluence of the Raritan River, South River and Lawrence Brook. Today this triangle is called Clancy Island and is part of East Brunswick Township. A map created by John Dalley in 1762 and in the possession of Princeton University shows the main house formerly owned by Thomas Lawrence (the great-grandson of the early settler on Bennett’s Island) in the northwest quadrant of what is now Clancy Island.[50] The Edgeboro Landfill currently takes up most, but not all, of Clancy Island.

An advertisement for the sale of Island Farm in December 1778 stated that “The dwelling houses, barn and outhouses” of the farm had been “destroyed by the enemy,” apparently in June 1777. Still, the advertisement observed that “its situation is remarkably high and healthy, commanding a most beautiful and extensive prospect from the place where the house stood, so much so, that the city of Amboy lies open to view.”[51] Based on this information, there are two likely sites.

Local historian Timothy J. Lynch found an 1888 topographical map showing a small rise of land east of Ellison Avenue, which runs just outside and parallel to the western boundary line of the Edgeboro Landfill. By superimposing this map on John Dalley’s 1762 map showing the location of Thomas Lawrence’s main house on Bennett’s Island, he concludes that this rise of land was the site of the former main house. This rise no longer exists; it is part of the Edgeboro Landfill in an area that now has level land. It appears this land is currently being used for landfill operations and not for burying trash. If the 1762 map is accurate in indicating the site of the Lawrence house, Lynch is likely correct. However, it is not certain the Dalley map is accurate in this regard. It is hoped the site of the main house is not inside the Edgeboro Landfill itself, New Jersey’s largest landfill, which is permitted to reach a maximum height of 165 feet above sea level.

Another possible location for the main house, also identified by Lynch, is at or near the intersection of what is now Ellison Avenue and Milton Avenue. This area is the highest point on the edge of a height of land running along Ellison Avenue. This height is just beyond the western boundary line of the Edgeboro Landfill; to the west is Exit 9 of the New Jersey Turnpike (Route 95), just before the highway spans the Raritan River. Of course, archeological work would be needed to confirm that this is the site of the former main house of the Island Farm, assuming that is even possible at this point. A tall portion of the landfill to the east of this site blocks the view of Perth Amboy to the east.

While this article is the first time the intriguing Battle of Bennett’s Island has been described in detail in a national publication, not surprisingly, a few local history buffs have been aware of it for some years, including local historians Ann Alvarez and Timothy J. Lynch.

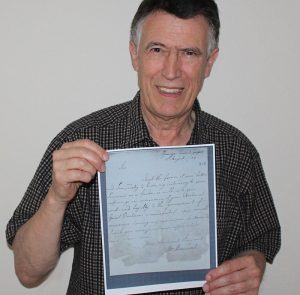

Chris Hay of Maple Ridge, B.C., Canada, displays a copy of a 1782 letter from Lieutenant Colonel William Harcourt of the Sixteenth Regiment of Light Dragoons. The letter, from the National Archives in London, confirms the services of Major Richard Witham Stockton, Chris’s 5th great grandfather, of the New Jersey Volunteers as the primary guide to Lieutenant Colonel Harcourt and a party of his dragoons in their capture of the Major General Charles Lee at a tavern at Basking Ridge, New Jersey. The discovery of this letter led to a two year research collaboration with American author Christian McBurney of Washington, DC, which in turn led to several Revolutionary War discoveries, including the story and location of the virtually forgotten Battle of Bennett’s Island.

Chris Hay of Maple Ridge, B.C., Canada, displays a copy of a 1782 letter from Lieutenant Colonel William Harcourt of the Sixteenth Regiment of Light Dragoons. The letter, from the National Archives in London, confirms the services of Major Richard Witham Stockton, Chris’s 5th great grandfather, of the New Jersey Volunteers as the primary guide to Lieutenant Colonel Harcourt and a party of his dragoons in their capture of the Major General Charles Lee at a tavern at Basking Ridge, New Jersey. The discovery of this letter led to a two year research collaboration with American author Christian McBurney of Washington, DC, which in turn led to several Revolutionary War discoveries, including the story and location of the virtually forgotten Battle of Bennett’s Island.

[1] Philander D. Chase (ed.), The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, Vol. 7 (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 1997), 498 n1.

[2] Jacob Dunham Recollection, 1830 or 1831, in Charles D. Deshler, “How the Declaration was Received in the Old Thirteen,” Harper’s Magazine (July 1892), 168 (Dunham was nine years old in July 1776).

[3] David Hackett Fischer, Washington’s Crossing (Oxford University Press, 2004), 340-43.

[4] Ibid., 343.

[5] Ibid., 350.

[6] Chase, Papers of George Washington, 7:497.

[7] Fischer, Washington’s Crossing, 352-56. For a description of seven foraging parties sent out by the British from New Brunswick from January 20 to February 23, 1777 that were attacked by Americans, see Harry M. Lydenberg (ed.), Archibald Robertson, His Diaries and Sketches in America, 1762-1782 (New York, NY: New York Public Library, 1930), 122-24.

[8] See George W. Dress, “Colonel John Neilson and the Revolution in New Jersey,” Master’s degree dissertation, New York University (June 1961), 31 (citing Neilson’s orderly book in the Neilson Papers held by the Rutgers University Library) (hereafter Dress, “Colonel John Neilson”).

[9] Israel Putnam to George Washington, February. 8, 1777, in Frank E. Grizzard, ed., The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, Vol. 8 (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 1998), 279.

[10] Both quotes in this paragraph are from Quoted in Dress, “Colonel John Neilson,” 33 and 37 (from Neilson’s orderly book).

[11] Report of the Bedford Commanders, February 7, 1778, quoted in Grizzard, Papers of George Washington, 8:280 n7.

[12] In a letter after his capture, Stockton stated that he had been ordered to “support” the British post at Bennett’s island. Richard Stockton to T. Peters, undated [probably about February 1778], Society of the Cincinnati. This suggests a portion of his troops had occupied Bennett’s Island prior to his arrival there.

[13] Walter T. Dornfest, Military Loyalists of the American Revolution. Officers and Regiments, 1775-1783 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Co., 2011), 326.

[14] Putnam to Pennsylvania Council of Safety, February 18, 1777 (from Princeton), in William Farrand Livingston, Israel Putnam, Pioneer, Ranger and Major-General, 1718-1790 (New York, NY: Knickerbocker Press, 1901), 342 (Putnam described Stockton as the enemy’s “renowned land pilot”); Alfred E. Jones, The Loyalists of New Jersey: Their Memorials, Petitions, Claims, Etc. from English Records (Newark, NJ: New Jersey Historical Society, 1927), 212 (“Double Dick”).

[15] See Christian McBurney, Kidnapping the Enemy: The Special Operation to Capture Major Generals Charles Lee & Richard Prescott (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2014), chapter 2 (the capture) and 60-61 (Stockton’s possible role), and Abductions in the American Revolution: Attempts to Kidnap George Washington, Benedict Arnold, and Other Military and Civilian Leaders (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2016), 43-45 and 178-79 (Stockton’s role in the capture).

[16] Cortland Skinner Submission in Support of Richard Witham Stockton’s Memorial, Febrary 28, 1783, British National Archives, AO 13/112A, 262. A copy of this letter was discovered and supplied to descendants of Richard Witham Stockton by Loyalist historian Todd Braisted. In turn, a copy of this letter and other copies of many other related documents were provided to the author by Chris Hay of Maple Ridge, British Columbia, Canada.

[17] Asher Dunham Memorial, March 7, 1786, in British National Archives, AO 13/21, 154. Cortland Skinner’s letter in support of Dunham’s memorial did not mention Dunham’s role serving as a guide in the capture of General Lee, and Dunham’s role in the abduction of Lee was not mentioned in any contemporary newspaper articles. This is in contrast to the mentions from those sources of Stockton’s role. Accordingly, there is less proof that Dunham participated in Lee’s capture than in Stockton’s case.

[18] For the size of Stockton’s force, see his Application for Reimbursement of Losses, March 23, 1784, in British National Archives, AO 13/3, MC 493. For the different battalions, see Todd Braisted, A History of the 6th Battalion, New Jersey Volunteers, The On-Line Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies, at www.royalprovincial.com.

[19] New Jersey Gazette, December. 8, 1778, in William Nelson, Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey, vol. III (Trenton, NJ: John L. Murphy Publishing Company, 1906), 11-12 (Thomas Lawrence, the great-grandson of the early settler of Bennett’s Island, advertised the Island Farm for sale); Adrian Bennet Sworn Statement, September 20, 1782, Inventory of Damages to the Goods to Thomas Lawrence, Middlesex County, B-4-5, War Damages 1776-1782, New Jersey Archives (describing house and other buildings that had been destroyed). Adrian Bennett, likely the descendant for whom Bennett’s Island was named, also claimed minor losses from British depredations on his Bennett’s Island farm, but not to any house or other structure. He may have been a lessee of Lawrence’s farm on Bennett’s Island. Adrian Bennet Sworn Statement, October 3, 1782, Inventory of Damages to the Goods of Adrian Bennett, Lawrence Island, Middlesex County, 22, War Damages 1776-1782, New Jersey Archives.

[20] Quoted in Dress, “Colonel John Neilson, 34.

[21] Putnam to Washington, Febrary 18, 1777, in Grizzard, Washington Papers, 8:362.

[22] See ibid (noting existence of a sixty-man guard one-half mile away from Bennett’s Island).

[23] Putnam to Pennsylvania Council of Safety, February 18, 1777, in Livingston, Israel Putnam, 342; John Neilson sworn statement, September 11, 1832, Revolutionary War Pension Application, National Archives, Washington, D.C. (NARA); Putnam to Neilson, February 17, 1777, Neilson Papers, Box 1, Rutgers University Library (copy). It is sometimes said that the riflemen hailed from Virginia, but that is not accurate, as Putnam’s February 18 letter and the February 7 Report of the Bedford Commanders (see note 11 above) make clear.

[24] Isaac Covenhoven sworn statement, September 19, 1832, Revolutionary War Pension Application, NARA.

[25] John Neilson sworn statement; Andrew McDowell sworn statement, June 5, 1833, ibid. In addition to Neilson and McDowell, the following New Jersey veterans stated in their pension applications that they were part of Neilson’s force that attacked Bennett’s Island: David Applegate, Clark Blandford, David Chambers, Isaac Covenhoven, Winant Dehart, John Ervin (mentions death of William Soden), Charles Fisher (by his brother Jacob), Cutlope Hancock, David Luker (mention’s Soden’s death), and Minard Vanarsdalen.

[26] Quoted in Dress, “Colonel John Neilson, 34 (from Neilson’s orderly book). The McDowell was Andrew McDowell. Same sources as in above note; William Stryker, Official Register of the Officers and Men of New Jersey in the Revolutionary War (Trenton, NJ: Wm. T. Nicholson & Co., 1872), 429 (Andrew McDowell started the war as a private in the Middlesex County militia and ended it as a lieutenant). The Fisher was likely Charles Fisher. Charles Fisher sworn statement, September 19, 1832, Revolutionary War Pension Application, NARA. Fisher was a sergeant, and later was promoted to lieutenant, of the 3rd Regiment of Middlesex County militia. Stryker, Official Register, 425 & 465. The Ogden was probably Benjamin Ogden, a private in the Middlesex County militia. Stryker, Official Register, 706-07. For the location of his house on South River about one-and-a-half miles from its mouth, see Thomas B. Wilson, Notices from New Jersey Newspapers 1781-1790 (Lambertville, NJ: Hunterdon House, 1988), 351. The identity of the deserter is not known. For the “very dark” quote, see Winant Dehart sworn statement, September18, 1832, Revolutionary War Pension Application, NARA.

[27] Cutlope Hancock sworn statement, December 18, 1832, Revolutionary War Pension Application, NARA.

[28] Application for Reimbursement of Losses, March 23, 1784, in British National Archives, AO 13/3, MC 493 (Stockton said he suffered a wound in the raid).

[29] Putnam to Washington, February 18, 1777, in Grizzard, ed., Washington Papers, 8:362.

[30] Ibid.; Lowery to Washington, February 19, 1777, in ibid., 371; Washington to New York Convention, February 20, 1777, in ibid., 387; Putnam to Livingston, February 18, 1777, in Carl E. Prince, ed., The Papers of William Livingston, Vol. 1 (Trenton, NJ: New Jersey Historical Commission, 1979), 241-42; John Neilson sworn statement. For William Soden being the sole attacker killed in the raid, see Putnam’s letter to Livingston and Neilson’s sworn statement.

[31] Extract of a letter from an officer of distinction, dated Princeton, February 18, 1777, in Pennsylvania Evening Post, February 20, 1777 (this letter is nearly identical to Putnam’s letters of the same date to Washington and Livingston; in this letter, Putnam ended with the postscript, “Since writing the above, the whole of the prisoners have arrived here”).

[32] Quoted in Dress, “Colonel John Neilson,” 36.

[33] John Neilson Obituary, The Evening Post, April 1, 1833 and The New England Magazine, 4:432 (1833). Captain Farmer was likely George Farmer, a private in the Middlesex County militia but a retired sea captain who was still called by this latter designation. See https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=8183647.

[34] Putnam to Washington, February 18, 1777, in Grizzard, ed., Washington Papers, 8:362.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Washington to John Hancock, February 20, 1777, in ibid., 381.

[37] Washington to New York Convention, February 20, 1777, in ibid., 387.

[38] Washington to Phillip Schuyler, February 23, 1777, in ibid., 434.

[39] Washington to Putnam, February 20, 1777, in ibid., 389.

[40] H. Hughes to Joshua Huntington, March 2, 1777, in “Huntington Papers,” Connecticut Hist. Soc. Coll. 20:53 (1923).

[41] Extract of a Letter from an Officer at Morristown, February 21, 1777, in Connecticut Courant (Hartford), March 3, 1777 and Independent Chronicle (Boston), March 6, 1777.

[42] Quoted in Livingston, Israel Putnam, 342.

[43] Extract of a Letter from Philadelphia, February 24, 1777, Philadelphia, in The Royal American Gazette (New York), March 6, 1777 and Scots Magazine, 39:248 (1777); William Howe to Washington, November 26, 1777, in Grizzard, Washington Papers, 12:413.

[44] Jones, Loyalists of New Jersey, 211-12; Dornfest, Military Loyalists of the A.R., 326.

[45] For Nielson’s election to brigadier general, see Minutes and Proceedings of the Council and General Assembly of the State of New –Jersey, in Joint-Meetings, from August 30, 1776 to May 1780 (Trenton, NJ: Isaac Collins, 1780) (reviewed on www.archive.org). Neilson does not mention his promotion to brigadier general in his pension application; and he submitted copies of his commissions and promotions to his pension application, but not one for brigadier general. John Neilson sworn statement.

[46] Quoted in Dress, “Colonel John Neilson,” 37 (from Neilson’s orderly book).

[47] John Neilson Obituary, The Evening Post, April 1, 1833 and The New England Magazine, 4:432 (1833); Chase, Washington Papers, 7:498; John Neilson sworn statement; William Livingston to Timothy Pickering, September 18, 1780, in Prince (ed.), Papers of William Livingston, 4:61–62.

[48] Jacob Fisher sworn statement, December 22, 1834, Revolutionary War Pension Application, NARA; Stryker, Official Register, 593 (private in Middlesex County militia).

[49] Charles Fisher sworn statement.

[50] A Map of the Road from Trenton to Amboy . . . ., March 8, 1762, by John Dalley, Manuscript Maps Collection, Princeton University Library.

[51] Same source as in note 19 above.

5 Comments

Now that Theaters of the American Revolution and The British Invasion of Virginia,1781 are out, what the next books in the JAR pipeline? I have 16 books on the Revolution published by Westholme. Keep up the good work!

Glad to hear you’re enjoying the JAR book series, Craig, as well as some of the other great titles available from Westholme. We do have more good titles coming, and you’ll see them announced here – but we’re not quite ready to reveal the next one yet!

Craig: It is terrific that you are such a strong supporter of Westholme and the JAR series, as they make possible the publication of new and exciting Revolutionary War studies. I have just started a new manuscript that will “shock the world” when it is published . . . but I have to keep a lid on the topic! Best, Christian

What if your time frame on this new possible book. I’m very intrigued.

Thank you for an intriguing article regarding the Battle of Bennet’s Island in East Brunswick, NJ. It was also referred to as Clancy’s Island when I was growing up as a boy on School House Lane in the 1950’s.

I use to ride my horse on the island long before it became a ugly landfill. Time does change things.

I remember the timber frame of a heavy beam and wooden peg structure still stood about half-way up the road leading to what must have been the farmstead. If one continued on the road it eventually followed a raised road surface through the marsh to the Raritan River. I can almost imagine battles taking place there and attempts to hinder the British from send supplies to New Brunswick.

It was a beautiful location and the farm land was rented out from time to time. I believe that Rutgers Agricultural College did some farming up there for a time.

By the way my distant relative owned 144 acres along the Lawrence Brook off Ryder’s Lane (now part of Rutgers). His name was Johannis Ryder. Well, so much for fond memories! Great stories to tell my grandsons.