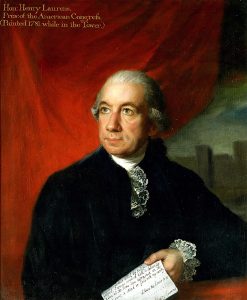

Henry Laurens, one of colonial South Carolina’s wealthiest and most politically powerful planter-merchants, was a conservative by nature.[1] When the imperial crisis began to drive Britain and its colonies apart, Laurens moved cautiously even when he disliked British policy. When Laurens refused to join the Sons of Liberty in protest of the Stamp Act, a mob accosted him at his home, suspecting that he was hiding stamped paper for the British.[2] The Sons of Liberty remained suspicious of Laurens throughout the imperial crisis, and Laurens even suspected that they had sometimes intercepted and searched his private mail.[3] Henry Laurens certainly believed in the ideals of English liberty. He certainly opposed British policies like the Stamp Act and Townshend Duties. Nevertheless, he believed in the rule of law and opposed the mob and those who led it just as strongly. Laurens even once described the leader of Charles Town’s Sons of Liberty—Christopher Gadsden—as “a very Grand Simpleton.”[4] What then pushed this conservative elite to become a leader of the American Revolution—eventually serving as the president of the Continental Congress? It was a slow transformation that has its roots in the nature of the eighteenth-century British Empire and its governance.

Henry Laurens experienced a series of personal conflicts with British placemen (i.e. political patronage appointees) as part of his business dealings in the 1760s. These incidents, especially with Vice Admiralty judge Egerton Leigh, slowly pushed Laurens closer to the break with Britain. These personal conflicts are complex, often revolving around delicate legal, business, and family affairs. They often seem petty and perhaps even not particularly important to the overall story of the coming of the American Revolution. However, Laurens’s battles, especially with Leigh, demonstrate a problem that greatly contributed to the break between Britain and its colonies and one that long pre-existed the well-known events of the imperial crisis of the 1760s and 1770s. The problem of placemen, and particularly their lack of accountability to provincial leaders and monopolization of important political offices, led to explosive political conflicts in nearly every colony but was especially fierce in South Carolina, where the provincial elite held especially great power over colonial governing institutions and jealously guarded its control of these tools of political power.[5]

Despite their extensive control over almost every branch of colonial government, the lowcountry elite had no authority over many offices filled by British appointees and had no direct way to hold these men accountable. The South Carolina elite often found themselves excluded from high office—increasingly so in the 1750s and beyond. No provincial, for example, ever held the post of royal governor. Placemen who did not share provincial agendas and priorities often held these top positions. Powerful (and often corrupt) placemen in the executive and judicial branches of government could intervene, block and frustrate the assembly’s efforts to manage provincial society, and maintain centralized political authority. The situation could become especially explosive if a placeman’s behavior seriously challenged the elite’s control over government institutions that the colonial legislative assembly had come to dominate and that the elite relied on to govern the colony. An examination of Henry Laurens’s battle with the most notorious South Carolina placeman of them all demonstrates the philosophical underpinnings of the colonial elite’s vision of government and the tactics they used to combat perhaps the gravest threat to their control of South Carolina’s political system—British placeholders.

Henry Laurens and Egerton Leigh had once been friends. Both enjoyed elite status in South Carolina, though Laurens’s derived from his great wealth as a planter and merchant and Leigh’s from his English political connections. Leigh came to South Carolina from England in 1753 along with his father Peter Leigh. Peter, former High Baliff of Westminster and another blatant placeman, took the family across the Atlantic upon his appointment as Chief Justice of South Carolina. Peter Leigh quickly proceeded to work for his son’s advancement, despite Egerton’s lack of legal education or qualifications. Egerton thus became clerk of the Court of Common Pleas in 1754. He received an appointment as Surveyor General in 1755. Leigh became judge of the Court of Vice Admiralty in 1761 and Attorney General in 1765. He held these last two offices to the end of the colonial period.[6]

Despite his unusually rapid advance in politics, Egerton Leigh enjoyed friendly relations with the lowcountry elite at the beginning of his tenure. He even gained a seat on the colony’s Royal Council. His multiplicity of offices, abuse of those offices, and defense of royal power eventually ended his friendly relations with lowcountry elite. Leigh married a niece of Henry Laurens, though Laurens was always critical of Leigh’s holding of multiple offices or places. Egerton Leigh even referred to himself as a placeman in 1773.[7] Thomas Lynch, a Commons House member and signer of the Declaration of Independence, described Leigh as a “rascal.” The terms were synonymous with the Leighs in colonial South Carolina.[8]

Leigh’s troubles all began over a dispute between Henry Laurens and the customs service during the Townshend Duties crisis. The case is long and complicated, but it boils down to Laurens battling with two placeholders—George Roupell (customs inspector) and Egerton Leigh (attorney general and vice-admiralty court judge)—again over regulations stemming from the new Townshend acts.[9]

Laurens’s ship Ann arrived from Bristol on May 24, 1768, loaded only with enumerated goods (those specific goods subject to customs duties). George Roupell searched the ship after its arrival and while it was being re-loaded on the dock. Quite shockingly to Henry Laurens, the customs inspector then had the ship seized on June 4. Roupell claimed the ship had been loaded with non-enumerated goods without having bond issued prior to loading. Laurens, who had just returned from Georgia, was unaware of the situation, and had not been able to get the appropriate paperwork before the ship was re-loaded. He actually arrived at the site with the proper paperwork while the ship was being loaded, but Roupell would not accept the bond, saying it had to be issued before any cargo could be put on the ship. Laurens had experienced problems with Roupell in the past and even took him to court on one occasion, so it appeared to Laurens that a royal official was out to settle an old score with him by manipulating regulations.[10] At this time, Henry Laurens was still friendly with Egerton Leigh, and Leigh cleared the charges against the Ann in the Court of Vice Admiralty when the case came before the court.

Unfortunately, Leigh’s ruling included technicalities that he hoped would placate Laurens while still protecting his fellow placeman Roupell. In the process, Leigh infuriated Laurens, offended his honor, and caused Laurens to launch an all-out assault on him personally and the entire British customs service in general. Leigh’s ruling did severely admonish Roupell, who clearly had manipulated the byzantine customs regulations of the British Empire in order to accumulate a fortune for himself in fees and fines.[11] Leigh wrote that customs regulations regarding loading enumerated and non-enumerated goods had been inconsistently enforced. Sometimes officials said bonds had to be issued before loading, and sometimes they allowed bonds to be given while the ship was being loaded, which Roupell did not allow in this case. Such behavior, Leigh said, could be used to “draw unwary persons into snares, and involve the most innocent in ruin.” In other words, officers like Roupell could set traps to collect more fees and fines, and Roupell was not the first customs collector in South Carolina to face this accusation.[12] Moreover, Laurens had actually listed the non-enumerated goods on the ship’s manifest and just failed to obtain the bond in time for loading. According to the fine letter of the law, Laruens simply had not delivered his paperwork at the proper time. Leigh wrote that “matters were so artfully conducted, that the claimant was unable to conform … before an actual seizure was made.” Judge Leigh suspected some “private design” on Roupell’s part.[13]

Leigh was already becoming an unpopular figure at this point, especially because of his ever-increasing multiplicity of offices. As Attorney General, Leigh was the sole government prosecutor in South Carolina and had power to decide which cases came to trial. As the lone Vice-Admiralty judge, Leigh had complete control of adjudicating imperial maritime law. Leigh’s service on the Royal Council often put him on the wrong side of conflicts with the assembly over tax and spending issues. Laurens claimed that he once advised Leigh to “shake off his pluralities” of office, and the South Carolina assembly itself complained to London about Leigh holding too many offices in 1766.[14]

South Carolina’s provincial leaders resented placemen, but Leigh’s multiple offices made him particularly offensive. However, as long as he did not directly challenge provincial authority, there were no overt conflicts. The Laurens case proved to be the incident that led to Leigh’s undoing. How could a friendship have fallen apart so dramatically, and how could Leigh, who seemed to be on Laurens’s side in this case, have faced such scorn? Leigh simply prevented Henry Laurens from launching a full political attack upon the hated Roupell in the courts. Hence, he attempted to stop the familiar political tactics used to remove an offensive—and in this case corrupt—placeman. Leigh chided Roupell for his inconsistent customs practices, but he allowed Roupell to clear his name and retain his place. The sole Vice-Admiralty judge refused to hold an obviously corrupt British official accountable.

Even though Leigh cleared Laurens of all charges and ordered restitution paid for the Ann’s seizure, Leigh ruled that the Ann was still technically liable for seizure under the law. Roupell, thus, had done nothing illegal. Leigh thus had Roupell swear an oath of calumny that his actions were not motivated by personal malice or revenge. Because Leigh ruled this way and issued a certificate of probable cause and seizure, Laurens could not sue Roupell in civil court and recover damages. Leigh, therefore, faced Laurens’s scorn.[15] He did not just want his ship cleared, he wanted the offending placeholder punished and humiliated. With legal action out of the question, Laurens used all his influence to bring pressure on Leigh through public shame, leading eventually to vicious back-and-forth attacks on both men’s reputations and honor.

Laurens, having been in his mind denied justice, printed a detailed attack pamphlet that effectively destroyed Leigh’s already shaky reputation. By the fall of 1768, Leigh resigned from the Court of Vice-Admiralty. Laurens explained his resignation by writing:

He felt the weight of public, almost universal contempt confirmed by his own consciousness of improper conduct too heavy for him to bear … his late misconduct should not pass without such public reprehension as may legally and with propriety be applied to it, as a caution to his successor. If the ministry knew how much injury is wrought to the true interest of Great Britain by the tyrannical oppression and misconduct of ministerial officers in America and the difficulty and almost impossibility of retaining redress upon complaints against them, they would certainly be more circumspect in their appointments.[16]

Even after the resignation, Laurens was not finished with Leigh. He wanted to punish him and drive him from South Carolina politics by permanently destroying his reputation. Moreover, destroying the reputation of one placeman would call the general and increasingly difficult issue of placemen into question.

Laurens launched his assault on Leigh’s character by publishing Extracts from the Proceedings of the Court of Vice Admiralty, which explained the details of his case and showed Leigh’s corruption. This pamphlet, published by William Fisher of Philadelphia and reprinted throughout the colonies in several editions, tied the issues of placemen and the imperial crisis together:

At a time when the powers of commissioners and other officers of the Customs in America are so greatly increased, and to render them still more formidable, the jurisdiction of vice-admiralty courts extended beyond its ancient limits—when too many men are employed in those offices, whose sole view seems to be amassing and acquiring fortunes at the expense of their honor, conscience, and almost ruined country … attacks of this nature concern every merchant on this continent.[17]

Clearly, Lauren’s personal feud with Leigh had led him to embrace the fight against imperial taxation and policy in a way that had never previously occurred to him. The pamphlet painted a damning picture of Leigh and of British colonial government in general.

Going into every detail of his and other similar cases, Laurens portrayed Leigh as a deceitful man who held office only for his own profit and who was entirely unfit as a judge.[18] In a letter to friend James Habersham, Laurens explained that the purpose of Extracts was to show the danger of giving one man too much power. He worried about placemen such as Leigh having “unlimited and uncontrollable powers over the property and reputations of us poor Americans.”[19] In general, Laurens concluded that imperial government itself was to blame. The customs laws were “numerous and intricate … a great science which requires a great deal of time and application to comprehend.” They were snares, designed to trap innocent, law-abiding merchants like himself so that placemen could extract their fees. The only recourse when one violated these laws was the vice-admiralty court, where one’s “property is at the disposal of a single judge, whom it is possible to suppose is a weak, unqualified person or corrupt trucking knave.”[20]

Leigh would not stand idly by and allow his reputation to be destroyed, so he responded with a pamphlet of his own entitled The Man Unmasked. Leigh began by stating the problem: “This is a hard and cruel case: to be stigmatized in print, and either to remain silent in which event the world will take every charge pro confesso or (bitter alternative!) to set myself up as a candidate for literary fame.”[21] The Man Unmasked went on to accuse Laurens of flaunting the legal system when it no longer met his needs. When the system ruled against him, Laurens decided to abandon the constitution and resort to his extra-legal means to get his way. Laurens, in other words, had utterly no respect for the rule of law. For his part, Leigh insisted that his role as judge was to interpret and uphold the law, which is exactly what he had done in the Laurens case.

He also stressed that “where the stream of justice” was interrupted by a corrupt judge, appeal to the king—“the fountain of justice”—was always available. Instead, Laurens chose to appeal to the people and attack the motives and character of a man who was only doing his duty to king and country. Leigh argued that Laurens was a man who only followed the law when it suited his personal and political purposes. Laurens’s attack upon Leigh was thus an attack on justice itself:

Nothing can be more idle and absurd, than for a party in a cause, to fly in the face of that judge, whom he has so lately and humbly implored for relief, to desert his constitutional remedy, and to set himself up as a Lord Paramount, to arraign his justice, load him with reproaches, vilify his resume, and blast … his reputation … to try him too by his own unlettered judgment, without color of law, against law, in defiance of the King’s authority, in exclusion of a superior jurisdiction clothed by the law of the land.[22]

It was then unjust in Leigh’s view for Laurens to, on the one hand, seek his aid as judge to resolve his case, only to turn around when the law did not fully support him and attack him as a man and an official. Laurens set himself up as a judge, and was a hypocrite for at first trusting the imperial system to resolve his problem and then attacking the same system when he did not get his way. Thus, Leigh’s approach was to defend his role as a judge and defend the imperial system, while attacking Laurens’s judgment, honor, and motives. Naturally, Leigh did not have the last word in this dispute.

Laurens was always very defensive in matters of honor and reputation. He was no stranger to dueling. He seems to have thus challenged Leigh to a duel over The Man Unmasked. Leigh, however, called off the duel, which left Laurens free to continue his attacks on Leigh’s character.[23] Laurens thus had another edition of his Extracts printed in Charles Town, but the conflict became much more personal. When the two had been friends, Leigh married Henry Laurens’s niece. Now, Laurens (in England at the time) got word that Leigh had impregnated his wife’s sister and had abandoned the poor woman on a ship, where she died alone. Furious, Laurens accused Leigh of adultery and murder, promising to take his case directly to the King.[24] Since Laurens was in England at the time, he had his son James carry on the attack at home. James Laurens wrote that his efforts had met with success, saying “he is almost universally condemned, despised, and shunned.” James hoped that Leigh would be driven from the colony, but he wanted Leigh to first confess his quilt.[25]

Leigh never did so, but his reputation in South Carolina was all but destroyed, and he became a social pariah. Nevertheless, he received a baronetcy from the crown and became Sir Egerton Leigh in 1772 and served as president of the South Carolina council from 1773 to 1775. His appointment and controversial tenure as president did permanent damage to that body’s already fragile reputation. In the end, Leigh resigned when he again faced public ridicule and attack for his role in the Wilkes Fund Controversy, which pitted the council against the assembly.[26] Laurens never succeeded in driving Leigh from the colony until the royal government fell, but he had utterly shamed him and destroyed his honor.

Egerton Leigh had hoped to unmask his former friend Laurens as a dishonorable man with no real sense of justice or regard for the law. The affair did unmask Laurens. It forced him to confront the deep flaws in the system of imperial government in a very personal way, and that confrontation led him ultimately to conclude that rule of law was more important than attachment to the British Empire and that British government itself would only continue to subvert the rule of law. The fight with Leigh did not cause Laurens to dramatically break with Britain. However, this incident and many others like it eroded his faith in a system that had made him rich and politically powerful. When that system seemed to increasingly threaten practical things like wealth and power (along with idealistic elements like English liberty), men like Laurens gradually awakened to the possibility of a colonial world that was no longer colonial.

It is hard to see much truly revolutionary activity in the Leigh episode, and there is little evidence that Henry Laurens became revolutionary (e.g. an advocate for independence or a republican) as a result of it.[27] Laurens never attacked the empire, George III or Parliament. He expressed no disloyalty or radical sentiment. He remained cautious and conservative (and suspected by more radical elements within the revolutionary movement as late as 1775) throughout the imperial crisis. This incident though strained Laurens’s attachments to Britain and the Empire, but there is nothing revolutionary about the incident itself. It is not directly connected to the imperial crisis or colonial resistance efforts to the Townshend acts, but it was one in a long series of provincial battles to make British placemen accountable to provincial authority. Nevertheless, those local battles—inherent to the politics of the British Empire—in this period must be understood to see how and why conservative elites like Laurens eventually came to embrace radical ideas like republicanism and separation from Great Britain.

[1] There is no modern, full-length biography devoted entirely to Henry Laurens. The most recent work is a dual study of Laurens and his rival Christopher Gadsden: David McDonough, Christopher Gadsden and Henry Laurens: The Parallel Lives of Two American Patriots (Selinsgrove, PA: Susquehanna University Press, 2000). The only biography entirely focused on Laurens remains David Duncan Wallace, The Life of Henry Laurens With a Sketch of the Life of Lieutenant-Colonel John Laurens (New York and London: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1915). For a study of Henry’s son John that often touches upon the father’s life, see Gregory D. Massey, John Laurens and the American Revolution (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000). For in-depth political context related to the Laurens-Leigh duel, see Aaron J. Palmer, A Rule of Law: Elite Political Authority and the Coming of the Revolution in the South Carolina Lowcountry, 1763-1776 (Leiden: Brill, 2014).

[2] “Henry Laurens to Joseph Brown, October 11, 1765,” in The Papers of Henry Laurens, ed. Philip Hammer and George C. Rogers (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1968-), 5:24.

[3] “Henry Laurens to James Grant, November 1, 1765,” ibid., 35. For a study of the artisans and their increased politicization during the imperial crisis, see Richard Walsh, Charleston’s Sons of Liberty: A Study of the Artisans, 1763-1789 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1959). For a detailed study of the committee structure of the resistance government, see Eva Bayne Poythress, “Revolution by Committee: An Administrative History of the Extralegal Committees in South Carolina, 1774-1776” (PhD diss., University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 1975). Two studies focus on the course and consequences of mob violence; see Pauline Maier, From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765-1776 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972) and Benjamin Carp, Rebels Rising: Cities and the American Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

[4] “Henry Laurens to James Grant, October 1, 1768,” in The Papers of Henry Laurens, 6:117. On Gadsden, see E. Stanley Godbold, Jr. and Robert H. Woody, Christopher Gadsden and the American Revolution (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1982).

[5] The placemen or placeholder issue is extensively covered in chapter five of Palmer, A Rule of Law. Many of the most important pre-imperial crisis conflicts are detailed in Jonathan Mercantini, Who Shall Rule at Home? The Evolution of South Carolina Political Culture, 1748-1776 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2007). See also Robert M. Weir, “The Last of American Freemen:” Studies in the Political Culture of the Colonial and Revolutionary South (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1986).

[6] Walter Edgar and Louise Bailey, eds., Biographical Directory of the South Carolina House of Representatives (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1977), 2:396-397.

[7] Ibid., 2:397-398.

[8] Robert M. Calhoon and Robert Weir, “The Scandalous History of Sir Egerton Leigh,” William and Mary Quarterly 26.1 (January, 1969): 1.

[9] The Townsend acts required that bonds had to be given before goods bound for outside the colony were even loaded onto a ship. The question of what constituted ships going outside the colony caused much confusion and trouble, as coastal schooners (never intended to leave the colony) became the targets imperial officials. If a ship were seized for violating the new regulations, the owner had to go before the Vice Admiralty Court, where he was essentially guilty until proven innocent. Regardless of verdict, the ship owner also had to pay all court costs. Robert Middlekauf, The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789, Rev. Exp. Edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 194-198.

[10] “Henry Laurens to Peter Timothy, July 6, 1768,” Papers of Henry Laurens, 5:730-733.

[11] Henry Laurens to William Fisher, July 11, 1768,” ibid., 735. British customs regulations were becoming increasingly complex in this period. An excellent overview of this complex topic can be found in Thomas Barrow, Trade and Empire: The British Customs Service in Colonial America, 1660-1775 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999).

[12] Another customs collector and placeman named Daniel Moore became embroiled in a heated controversy with Charles Town’s merchants (led by Henry Laurens). The merchants accused Moore of charging high and arbitrary fees and not posting any official list of fees. Moore apparently even threatened those who challenged his practices with violence. Egerton Leigh, the vice-admiralty judge, refused to hear a case about Moore’s abuse of the fee structure, and he threatened, as attorney general, to prosecute any group of merchants who would attempt to bring any suit against Moore in civil court. The merchants took their case to London through the colonial agent and eventually drove Moore from the province. A detailed narrative of this case can be found in Palmer, A Rule of Law, chapter 5, “All Matters and Things.” The basic facts, from the merchant’s point of view, were published in a pamphlet that did great damage to Moore’s reputation: A representation of facts, relative to the conduct of Daniel Moore, esquire, collector of His Majesty’s customs at Charles Town in South Carolina (Charles Town: Charles Crouch, 1767).

[13] “Extract from the South Carolina Gazette, July 11, 1768,” Papers of Henry Laurens, 742.

[14] “Henry Laurens to William Fisher, August 1, 1768,” in Papers of Henry Laurens, 6:3.

[15] Henry Laurens, Extracts from the Proceedings of the Court of Vice Admiralty, Second Edition (Charles Town, David Bruce, 1769).

[16] “Henry Laurens to William Cowles and Co., October 15, 1768,” Papers of Henry Laurens, 6:136.

[17] Laurens, Extracts from the Proceedings of the Court of Vice Admiralty.

[18] “Henry Laurens to William Fisher, September 12, 1768,” Papers of Henry Laurens, 6:92.

[19] “Henry Laurens to James Habersham, August 15, 1769,” Papers of Henry Laurens, 7:124-125.

[20] Laurens, Extracts from the Proceedings of the Court of Vice Admiralty.

[21] “The Man Unmasked,” Papers of Henry Laurens, vol. 6, 455.

[22] Ibid.

[23] “Egerton Leigh to Henry Laurens, May 29, 1769,” Papers of Henry Laurens, 6:580,

[24] “Henry Laurens to Egerton Leigh, January 30, 1773,” Papers of Henry Laurens, 8:556.

[25] “James Laurens to Henry Laurens, October 19, 1773,” Papers of Henry Laurens, 8:125.

[26] Edgar and Bailey, Biographical Directory of the South Carolina House of Representatives, 2:397-398. A detailed account of Leigh’s troubles with the council is found in Calhoon and Weir, “The Scandalous History of Sir Egerton Leigh,” 67-74. Leigh’s involvement in the Wilkes Fund Controversy (a major dispute between the South Carolina assembly and the royal governor) also helped lead to his downfall in the colony. That dispute, along with a pamphlet on the case by Leigh, is detailed in Jack P. Greene, The Nature of Colony Constitutions: Two Pamphlets on the Wilkes Fund Controversy in South Carolina by Sir Egerton Leigh and Arthur Lee (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1970).

[27] Mercantini, Who Shall Rule at Home, 235.

2 Comments

Thank you, Aaron, for putting this together. It’s not a headline story but a key one. As you point out, Laurens was an extremely reluctant revolutionary, if he can be called that at all. His estrangement from his childhood buddy Gadsden reveals how conservative he was by nature. But he did join in the end, and his run-in with Leigh, which seems so small to us now, was huge at the time and did place Laurens at odds with a Royal government that he otherwise favored. I featured Laurens as one of seven protagonists in my book “Founders,” using him to represent the conservative (and slave-owning) wing of US figures. Plus, HL’s story gives us John Laurens — a true revolutionary. This father-son relationship is absolutely fascinating.

This whole affair makes me giggle, especially the part in which Henry writes to James Habersham (1767) and notes how he basically just “had to” punch Daniel Moore (Leigh’s accomplice in HL’s mind) in the nose. The only note I wanted to mention was that it wasn’t HL’s son, James, who took over his post in SC while HL was in England; it was his brother, James. His son James was only around two at this time.